For some time, we’ve been reading of a Central American Crisis that is threatening to run the Middle East Crisis off the front page.

Closer to home, there is an Oil Crisis, an AIDS Crisis, and a Farm Crisis.

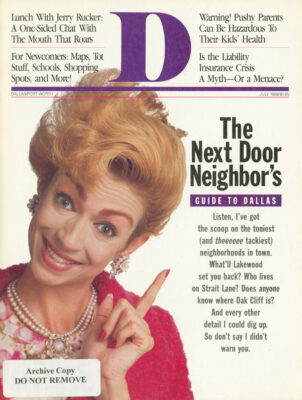

Now, just when one would think that we were all crisissed out, the Liability Insurance Crisis marches into town with floats, bands, and a mounted posse.

A panic in the insurance industry? In 1980, American insurance companies collected premium totals that amounted to $17.8 billion. That’s 75 percent of what the IRS collected from taxpayers in that year.

At the 3,000 Sears stores nationwide, which sell everything from tweezers to DieHards, 50 percent of the money spent goes through the Allstate insurance window. Yet property/casualty insurers are reporting industry-wide annual losses of $3.8 billion for 1984 and well beyond that for 1985. The U.S. mainland was hit with six hurricanes in 1984, and that was expensive for the insurance industry. But it’s nothing compared to the tempest brewing on another front.

The American civil justice system is the scene of the controversy, and the insurance industry is spending $12 million nationwide ($1 million in Texas) on an ad campaign designed to heighten public awareness of the so-called liability crisis. The issue now looks to be the leading political struggle in the next session of the Texas Legislature.

Among the interested onlookers will be the walking wounded, the liability policyholders who have already felt the harpoon of rising rates. Operators of day care centers, for instance, are faced with staggering premium increases running up to 1,000 percent.

Phil Cobb, president of the Dallas-based Prufrock restaurant and bar chain, says that liability premium rates have forced some people in his business, most of them in the Midwest, to take the monumental risk of operating with no insurance at all.

’They set up dummy corporations to front their restaurant,” Cobb says. “Then, if they get hit with a big dram shop verdict [negligence for over-serving a customer who causes an accident], they simply declare bankruptcy,” Cobb says.

For several years, Cobb has been one of the backers of the trolley line that will run from the Arts District up through the bistro/ gallery strip along McKinney Avenue. He’s seen the liability crunch up close. “If the bar and day care people think they have an insurance problem, let ’em try to operate a privately owned transit system. So far. we haven’t found any insurer who’ll even talk to us, much less negotiate terms.”

The postman is no longer a welcome sight at city hall. Many Texas municipalities have recently been “redlined.” In other words, they can’t find an insurance company to insure them at any rate, no matter how steep the escalation. Dallas has been self-insured since last May, when the city was faced with a whopping 1,128 percent rate increase for liability insurance.

Some doctors claim their malpractice rates threaten to drive them into faith healing. A family practitioner recently refused to puncture an abscess that was causing his patient extreme discomfort. Why? Because the fine print in the doctor’s malpractice insurance policy defined the draining of the abscess as a surgical procedure. “According to the terms of my insurance, I am no longer allowed to pick up anything sharp,” he says.

Some physicians contend that because of the stratospheric rise in malpractice premiums, they are being forced to practice “defensive” medicine. Many are subscribing to the Physicians’ Alert software service, which enables them to identify potential patients who have a history of filing malpractice, product liability, or personal injury lawsuits. Some studies show that 70 percent of medical malpractice suits are filed by “repeat victims.” While such screening may not be purely in the spirit of the Hippocratic oath, doctors contend that they must resort to all of the safeguards they can find to survive the caprices of what has become known as the litigious society. A decade ago, we were accused of being a lascivious society, which meant that we were all sex crazy. The litigious society, on the other hand, is courthouse crazy-Liability insurers contend that baskets of cash are being given away in frivolous cases by juries across America. Horror stories circulate, like the one about the breeding bull that died of an overdose of insecticide it inhaled in an artificial insemination lab in Matagorda County on the Texas Gulf Coast. The jury awarded the owner of the bull $1.5 million in actual damages (the amount the bull might have earned in its lifetime) and $7 million in punitive damages against the owner of the breeding stall.

Insurers, particularly in the property and casualty area, insist that individuals who read and hear of these strange events are led to conclude (hat the civil courtroom is one of the last outposts of the all-American free lunch. And egged on by plaintiffs’ lawyers working on contingency and eager to collect a prearranged one-third to one-half cut of any settlement or jury award, they are clogging the court dockets with dubious, long-shot lawsuits.

In Texas, legislative reforms are being drawn to remedy these alleged abuses of the courts system, including a $100,000 ceiling in the area of non-actual or non-economic damages-i.e., pain and suffering and punitive damages.

Another target for elimination is the concept of joint and several liability, the mechanism that enables the plaintiff to sue a variety of codefendants. Among other things, joint and several liability is frequently used to drag in the manufacturer of a product that might have been involved in an accident.

Accomplished plaintiffs’ lawyers are skilled at sniffing out any potential co-defendant who has the insurance coverage adequate to sustain a massive jury award. For instance, a sixteen-year-old girl in Los Angeles was broadsided by a drunk driver who ran a stop sign. The city of Los Angeles was held to be 22 percent liable due to the poor visibility of street lane lines, even though it was raining when the accident occurred . Since (he negligent driver had minimal liability coverage, the city’s insurance must pay almost all of the $2.6 million jury award unless it is overturned on appeal.

Insurers are also pursuing relief in the form of structured awards that would enable payments to be spread out over a period of years rather than paid in a lump sum. They are also pursuing avenues that would enable judges to slap financial penalties on litigants who present what the judge deems a frivolous lawsuit.

These are the highlighted features of the tort reform package that will be presented in the upcoming 70th session of the Texas Legislature. The situation may provide unprecedented measures of acrimonious dialogue and inflammatory interchange in the Austin statehouse as the powerful doctors’ and lawyers’ lobbies do battle. The tort reform issue covers many territories, from business to political to legal, and all Texans will be affected by the results.

In Texas, the tort reform program is backed by a group known as the Texas Civil Justice Coalition, a group of Austin lobbying heavy weights that includes the Texas Medical Association, the Texas Hospital Association, the Texas Transportation Association, the Texas Press Association, the Texas Association of General Contractors, and, of course, the insurance industry.

The coalition accumulated a serious war chest to fund hundreds of House and Senate races throughout Texas. Also, the TCJC is keenly interested in the races for the Texas Supreme Court. Advocates of tort reform in Texas say that in recent years, the Texas Supreme Court has undergone an ideological swing toward the pro-plaintiff side, helping to make Texas a healthy climate for the plaintiff lawyer.

“The Texas Trial Lawyers Association has been really effective in getting its people elected in recent years,” says Kay Bailey Hutchison, a Dallas Republican activist now working on behalf of the Texas Civil Justice Coalition. The most profound effect of this, she says, is that Texas has joined hands with the rest of the American litigious society and has become a “plaintiff’s haven.”

Dallas attorney Robert Greenburg, whose firm usually defends the defendant in personal injury cases, is somewhat more outspoken. He says that small business and eventually the fabric of the American free enterprise system are threatened unless tort reform legislation is enacted. “I can see why the plaintiffs’ lawyers are so adamantly opposed to tort reform,” Greenburg says. “Because if it passes, they’ll find themselves going the way of the independent oil man.”

Austin-based media consultant George Christian has been retained to engineer the reform coalition’s multifaceted public relations campaign, which even the trial lawyers concede has been effective. Throughout the spring and early summer, editorial pages throughout Texas have been picking up the cadence. The Dallas Morning News bemoaned “the mind-boggling propensity of juries to hand out huge awards to plaintiffs in personal injury cases.” The Fort Worth Star-Telegram slammed our society’s “casual and morbidly cynical absolution from responsibility” symbolized by the popular bumper sticker that reads “Go ahead and hit me. I need the money.” The Tyler Morning Telegraph went further, declaring that “the justice system as we know it” has been replaced by a money-hungry system that encourages plaintiffs to sue at the drop of a hat.

The backers of the tort reform manifesto in Texas found additional ammunition for their cause in 1985 from two separate and totally unexpected events. The lawyers circling around the families of the Delta crash victims, slithering from the woodwork like ticket scalpers at the Final Four, did nothing to enhance the position of attorneys in the public eye. The scene recalled Melvin Belli’s memorable quote: “I resent being called an ambulance chaser. I get there before the ambulance.”

And then came the $10.53 billion verdict rendered by a Houston jury against Texaco. Even though the issues in that case have little to do with the legal reforms to be debated in Austin, the tort reformers point to that case as an illustration of what can happen when juries run wild.

The trial lawyers, on the other hand, will tell you that the current liability crisis is just a cynical power play on the part of Big Insuranee, a neatly camouflaged manipulation that utilizes the civil justice system as the convenient excuse to drive premium rates through the roof, limit jury awards, and deprive all but the wealthy of access to the courts.

One of the most devoted spokespersons for this point of view is Dallas trial lawyer John E. Collins, who casts a jaundiced eye at insurance company claims that wild-eyed juries are about to sink their boat. He notes that in the last two years, property/casualty insurers are reporting industry-wide operating losses for the first time since 1906.

“Not too bad for an industry that wants to eliminate or reduce the citizen’s right to a jury in civil cases,” Collins says. He adds that his figures come from the industry’s own Insurance Information Institute. According to Collins, the Insurance Institute concludes that the industry’s recent woes are due to “bad weather and an insurance price war of five years ago.” There is no mention of runaway juries and million-dollar awards. Collins further notes that on Wall Street, insurance stocks gained about 40 percent in 1985, strongly outpacing the market’s overall performance. He concludes that other industries should be so lucky during a down cycle.

Armed with a small mountain of statistics, Collins contradicts the tort reformers. One of his favorite exhibits is a chart showing that between 1980 and 1984. when society supposedly went from lascivious to litigious, new personal injury cases filed in the Texas Civil Courts rose by 15.5 percent, a figure Collins finds unalarming. “That’s not even at a rate equal to the population increase in Texas during that time,” he says.

Nationally, the figures are closer to 7 percent during that period, according to numbers provided by Robert Roper of the National Center for State Courts. “There’s no evidence of a litigation explosion,” Roper says.

The depth of the so-called “crisis” is a matter of continuing debate. Dallas insurance analyst Charles E. Greer points out that while forty-six property and casualty insurers went out of business in 1985-three more than in 1984-fifty-eight new companies were formed. In addition, some of the celebrated liability outrages being used to win sympathy for the insurers are highly suspect. In Kansas, a tort reform ad told the story of a man who successfully sued a lawn mower manufacturer after he injured himself holding the power mower to trim his hedges. A good story, but the ads had to be taken off the air when no one could verify the event. Trial lawyers insist that the insurance industry is circulating twelve to fifteen such apocryphal tales, all of them exaggerated or made up entirely. “It’s lobbying by anecdote,” says Dallas Congressman John Bryant of the tort reform legislative campaign. “It’s very effective.”

Collins is quick to refute the tort reform argument that knee-jerk juries are recklessly handing out huge parcels of cash to greedy plaintiffs. In 1985. in Dallas County state and federal courts, the jury sided with the plaintiff in only 30 percent of the personal injury cases not involving traffic accidents, 31 percent of those involving traffic accidents, and 40 percent of the workmens’ compensation cases. Of twelve product liability cases that went to a jury, the plaintiff won just three.

In the volatile area of medical mal-practice, say tort reform oppo-nents, there is no crisis. “It’s almost impossible to win a medical malpractice case, because the juries have so much respect for the image of the doctor and because it is so rare that a doctor will offer expert testimony against a colleague,” John Collins says. He cites a case in Tarrant County in 1984 when fourteen-year-old Anthony Ray Elmore entered a hospital for eardrum surgery and awoke in the recovery room to discover that he’d undergone a successful cataract operation on each of his eyes.

The boy’s mother took the surgeon, Dr. Ronald Antinone, to court. But the doctor convinced a jury that it was not his responsibility to check out those plastic wrist tags that all patients wear into the operating room. Therefore, the jury found that the doctor wasn’t negligent. Anthony Elmore got nothing.

Statistics confirm that Dallas juries are extremely reluctant to rule against the physician. Since 1969. a total of 147 malpractice suits have been tried in Dallas. Only twenty-five of the plaintiffs in those cases were awarded any money at all. The total of malpractice awards in Dallas over that seventeen-year period was $1.1 million; an additional $4.5 million remains on appeal.

Both sides in the tort reform issue are equipped with volumes of statistics and figures and tales of outrageous abuses that justify their causes and fan the flames of incendiary exchange. The old-time railbirds who like to occupy the ringside seats in the House and Senate chambers can hardly wait. The Great Liability War promises to be a rumble of memorable proportions.

The occasion is an interim House/Senate subcommittee study session to hear the various arguments on the tort reform matter.

It is late February 1986, and the “study session” is billed as a dress rehearsal for the formidable legislative debate in the 1987 Legislature. The site is the old Texas Supreme Court chamber in the state capitol building. All of the special interests are on hand. The joint is packed.

The first person on the Saturday morning agenda is Texas Attorney General Jim Mat-tox, the self-starting chainsaw of Texas politics. The attorney general is here to tell the committee members that he thinks the insurance industry crisis is a massive hoax, orchestrated by the worldwide reinsurance cartels and Lloyds of London in particular.

“The insurance industry, through its front organizations like the Insurance Information Institute, is investing millions of tax-sheltered dollars in a gigantic propaganda campaign to publicize what they euphemistically call the civil justice reform.’ To me, it is becoming clearer all the time that the people of this state are being asked to buy a pig in a poke. What do we really know about this pig? Very little. We are only told that the pig’s name is tort reform.”

Mattox gathers steam. “By the way, would a pig under any other name smell so sweet?” the A.G. wants to know. “Could this pig be an English pig named Lloyd? Yet we are not allowed to see this pig. In fact, the sacked pig is being hidden from us behind a bunch of liability insurance bramble bushes.”

At the end of his presentation, Mattox offered to investigate possible collusion on the part of the liability carriers.

The next act on the subcommittee show card consisted of the testimony of three men: Andre Maisonpierre, president of the Reinsurance Association of America; T, Darring-ton Semple Jr., resident counsel of American Reliance Insurance of New York, and Charles W. Havens III, U.S. legal representative of Lloyds of London.

Havens, who had endured Mattox’s pig soliloquy, testified that runaway litigation is basically unique to the U.S. He said that in Great Britain and throughout most of Europe, contingency fees-another target of the Texas Civil Justice Coalition-are unheard of.

After a lengthy session of cross-examination from the subcommittee, dealing largely with the question of whether liability premiums would decrease if tort reform measures are enacted, the insurance men conceded that that was “unpredictable.”

However, Lowell Junkins, an attorney from Iowa, said that in California, Iowa, and the province of Ontario, tort reform measures have been in place for some time while the premium rates and the liability crisis in general continue to escalate.

In response, Sid McLemore of the Texas Licensed Child Care Association testified that he favored tort reform, reporting an incident in which a child at a day care center he operates fell off the john and cut his lip. The injury required five stitches. The parents of the child, filled to the gills with litigious rapture, felt that the day care center was negligent and filed suit, seeking $100,000 per stitch. The family settled out of court for $5,000, a figure McLemore finds absurd.

You wonder about the questions thoughtful jurors must ask themselves while pondering the life or death of the defendant in a capital murder case. Consider then what the juror is called upon to do in certain civil cases which involve placing a strict dollars-and-cents value on a human life. Or a portion of one.

You’re wrongfully injured on the job and lose both legs. How much would you take for your legs? Sixty grand? Two million? People on juries must make these kinds of determinations all the time, even though civil trials don’t often get publicity unless they involve a celebrity or an airline disaster.

There wasn’t a paragraph in either Dallas paper about a wreck on an East Texas interstate highway when it happened five years ago, and there was very little coverage of the trial that resulted from the accident. While the trial was ignored by the media, it incorporated all the elements now under debate in the tort reform struggle.

Pete Larson, thirty, was driving a little over fifty-five miles per hour in the right-hand lane near Tyler, heading west toward his home in Van, Texas. He was accompanied by his wife, Robyn, and their two children. As Larson’s van neared an underpass, he glanced into his side mirror and noticed an eighteen-wheeler barreling down the road at high speed in the left-hand lane.

Then Larson watched as the big truck inexplicably maneuvered in behind him and began to bear down. And, in a nightmarish microsecond, Larson realized that the truck wasn’t going to slow down, Before Larson had time to react, the eighteen-wheeler slammed into the rear of the van. The truck literally shoved the van down the pavement for about a hundred yards, and then the van went rolling over and over down an embankment, like a stagecoach going over a cliff in a western movie.

The four occupants of the van were spilled out in various directions along the way.

By now, the eighteen-wheeler had jack-knifed. A witness said the truck driver casually climbed from the cab and smoked a cigarette, waiting for the highway patrol to arrive. He didn’t lift a finger to help the injured.

As it turned out, the children weren’t hurt badly, but Robyn suffered a shattered pelvis and massive internal injuries. Larson will spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down.

The Larsons, two more operatives in the American litigious society, felt they were entitled to some compensation. An East Texas attorney referred the couple to Frank Branson, a Dallas trial lawyer who specializes in plaintiffs’ defense work. In the last five years, Branson has secured fifteen verdicts or settlements for his clients that were $1 million or more.

Usually, in personal injury cases, the insurer will present what it will contend is a fair figure; if the plaintiff doesn’t like that one, the matter goes to court. The defense lawyer representing the insurance company can file motions and create delays that can keep the case out of a courtroom for years. The plaintiff, frequently in desperate financial straits, will often wish he’d taken the first offer.

Once a case does reach a jury, it’s a crap shoot, with the plaintiff frequently winding up with nothing. And the plaintiffs who do receive a jury award can count on additional years of appeals before they ever see a nickel. An additional hazard is that the trial judge has the authority to knock down a jury verdict or eliminate it entirely, instructing a verdict for the defense.

Branson, like many plantiffs’ attorneys, puts together an elaborate video presentation dramatizing his client’s plight, complete with key testimony from depositions. He presents the video, along with his settlement figure, to the defense lawyers, taking a “you can pay me now or pay me later” posture.

In the Pete and Robyn Larson case, the defense lawyers chose to go to trial, despite some damaging testimony in the video show.

The truck driver admitted that he’d had only about four hours’ sleep during the seventy-two hours prior to the collision, a blatant violation of Department of Transportation regulations. The driver said that he was acting on the orders of his boss, the owner of the Los Angeles-based trucking line. He said he didn’t know how fast he was driving the truck when he rammed into the Larson van. In fact, he didn’t remember much at all about the collision.

Pete Larson was the picture of a bitter man as he sat in his wheelchair and testified to the jury. He’s still allowed to work, but really can’t do much and feels that his boss is providing charity to a basket case. He can’t hunt or fish or play catch with his boys anymore. Medical bills continue to mount astronomically. The day-to-day care of a paraplegic is shockingly expensive. But most painful of all, Larson says, was the termination of his sex life with Robyn.

The defense built its case around two points: that Larson could have avoided that accident if he’d really been watching what he was doing, and that the figures Branson presented as the Larsons’ potential loss of earnings ($583,000 for Robyn, $1.432 million for Pete) were exaggerated.

When Branson presented his final summary to the jury, he said that corporate greed-in this case, the trucking line flaunting DOT regulations “to make some extra bucks”-cost Pete and Robyn Larson their chance to enjoy life and left them in a total shambles.

Then Branson advanced into the area of damages for pain and suffering, which he figured might be touchy going with an ultra-conservative box of jurors in Smith County (Tyler), which rarely sees the million-dollar verdict.

“Small-town juries usually go light on the pain and suffering thing,” says Houston plaintiffs’ lawyer Kirk Purcell. “Their attitude is, ’Life’s hard. That’s why we’ve got churches.’”

In his final summation to the jury, Branson asked the jury to “send a message” to errant truckers. “Pain is what they use to make prisoners of war talk. How do you make a corporation feel pain? In their one vulnerable point-their pocketbook, their pocket of power. So use that whip and teach me California trucking company that East Texas is not a place to boogie through and that they can’t make a battle zone out of I-20.”

When the jury finally reentered the courtroom, they had decided that Pete and Robyn Larson were entitled to $5.6 million-$3.3 million in actual damages and $2.3 million in punitive damages. Rather than appeal, the defense offered to pay out something in the neighborhood of $3 million. The Larsons opted to take the money.

The trial lawyers charge that, under the tort reform measures being sought, the Larson award would have been whittled to a fraction of the final figure. They might have received nothing.

And without contingency fees, they add, the Larsons would never have been able to afford a lawyer of Branson’s experience and stature on an hourly fee basis.

Branson says that the plaintiffs’ lawyers, even those who continue securing clients with multimillion-dollar potential, must go into battle at a distinct disadvantage.

“The insurance companies traditionally hire major and established law firms to handle their big cases,” he says. “The firms have the clout and they’re belter financed [than the average plaintiffs’ lawyer]. And you have to remember that defense lawyers get paid whether they win or lose. This is the prime reason why the defense tactic is to file more and more motions, seek more and more hearings, and gain more and more delays. They’re just clocking time.”

Branson also is quick to point out that the attorney who takes a case on a contingency basis frequently ranks right there with the guy who takes a second mortgage on the old homestead and plunges it all into (he Saturday Trifecta at Louisiana Downs. In order to enter the courtroom properly armed to win a case against a major defense firm, the plaintiff will have to invest in the hiring of expert witnesses, private investigators, illustrators, and a legion of other specialists who constitute the support staff. In the case of the Pete and Robyn Larson situation, Branson had already spent $70,000 to prepare the case. “I’m almost embarrassed to go into the figures because they are so large,” he says.

“The person, or survivors of the person, who receives the million-dollar-plus settlements and awards, in virtually all cases, were wrongfully killed, blinded, or turned into a vegetable,” Branson says. “And what does the money provide? What kind of satisfaction do Pete and Robyn and their kids get from the money? Not much.”

Of course, whether or not that East Texas jury gave the Larsons too much money will be part of the great legal debate of the next five years and maybe longer.

Pete and Robyn Larson, by the way, have split up.

Related Articles

D CEO Award Programs

Winners Announced: D CEO’s Financial Executive Awards 2024

Honorees in this year’s program include leaders from o9 Solutions, Baylor Scott & White, and Texas Capital, as well as our Constantine ‘Connie’ Konstans Award winner Mahesh Shetty of ILE Homes.

Basketball

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Mavs-Clippers Game 2

A gritty game draws Dallas even in the series.

By Iztok Franko and Mike Piellucci

Baseball

What Should We Make of the Rangers’ Accidental Youth Movement?

It's been 26 years since a defending World Series champion leaned on this many young players out of the gate. In Texas' case, that wasn't the plan. But that doesn't make an influx of former first-round picks a bad thing, either.