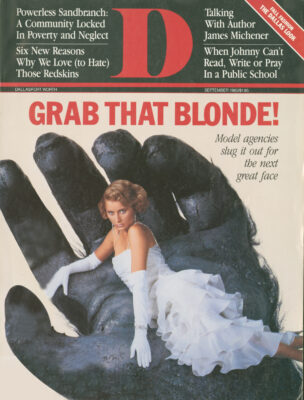

THE RUMORS BEGAN last spring. Dallas’ best blonde was ready to make a switch. Clarke Hanson, who made more than $120,000 in the past year as Dallas’ top blonde model, had told friends that she had become unhappy at the Tanya Blair Agency. She wanted to leave. And she wanted to go, of all places, to the Kim Daw-son Agency.

The news had to be received with a touch of irony. Hanson was the lead filly in a stable of Tanya Blair models that made such an aggressive assault on Kim Daw-son’s fortress in 1983 that anyone could see that the modeling industry here was entering a fevered and competitive era. In Dallas, the female model has long been the symbol of everything glamorous and elegant about the city, her face not only fashioning the image of what is beautiful but also what is successful. A star model sweeping into a local restaurant created the kind of buzz among patrons that normally was reserved for the arrival of professional football players. For years, the “Dallas look” has been goggled at and exploited. National television and magazine reporters came to showcase Dallas women primarily because of the look they saw in the Dallas models.

But because of a new kind of model like Clarke Hanson, all of that was changing. The tall, refined Tanya Blair, sensing that the market was ready to go European, blasted forth and knocked Kim Dawson’s dynasty for a loop. For more than 20 years, Dawson had been the mother figure to the city’s loveliest women. In large part, she decided which models would make it here, whose look would succeed and who should move somewhere else. Blair brought in a different set of rules. The fresh, Texas beauty look was no longer the only look in town. As Blair put it, “a model could get away with looking weird.”

The Dawson Agency rebounded, improving its pool of models. It began to fight its way back to the top of the beauty heap-and there were some who felt that the defection of Hanson would be just the thing to give them the edge.

Although in this multimillion dollar business, the move of one top model from one agency to another would not cause much of a financial hardship, such a loss could cost a lot in prestige-which made the rumors of Hanson’s discontent even more significant. Her summer of indecision was perhaps the most conclusive sign of the way increased competition has shaped Dallas modeling. Today, the agencies skillfully promote their existing models, hunt down new talent and ballyhoo their finds. Even in the last 60 days, new modeling agencies have been established, creating an even more intense, often acrimonious conflict, all because of an inexorable drive to sign up the next star-someone who, if she’s lucky, might last all of two years.

FOUR AGENCIES represent all but a fraction of the fashion models in Dallas. Kim Dawson is by far the largest, with more than $6 million in 1984 bookings, but much of that comes from her large broadcast talent division, children’s division and her fashion shows. Dawson does represent the largest number of “pure” fashion models in the city, with roughly 180 women and 80 men. Tanya Blair, with an average of 75 female and 15 male fashion models, is second largest, but more than 80 percent of her $2.5 million in last year’s bookings came in the fashion division. Then there is the Mike Beaty Agency at $1.5 million and the Sarah Norton Agency at $1.4 million. Agencies make their money by taking 20 percent of the money brought in by their models.

It is most significant to note that while Blair has just moved her offices into the new Grand Bank Building that looks upon the skyscrapers of downtown, Dawson has never once considered moving from the place where her dynasty began-in an unadorned back corner of Trammell Crow’s Apparel Mart. Crow made a deal with Dawson in 1963 when he decided to create an apparel center for the Southwest. He told her if she would move to the Apparel Mart, she could have an exclusive contract to produce the fashion shows there and pick all the models.

At the time, Dawson, who for 20 years had been one of the long-limbed, graceful floor models for Neiman-Marcus, was struggling with her own two-year-old modeling agency. No one had ever tried something like it before in Dallas, and the only regular work she could find for her six models was one fashion-luncheon show a week at the old Baker Hotel. The pay was $15 per model. “It was a ridiculous occupation,” Dawson says. “Everyone wanted to get out.” (One of Daw-son’s first discoveries was a blonde model named Frances Marlow, who did get out. She is now Judge Frances Maloney, a state criminal district court judge at the Dallas County courthouse.)

Dawson agreed to Crow’s offer, and in 1964 produced four fashion shows. She tried to do innovative things-at one show sticking her models in a sailboat which floated around in a pool on the stage. During another she had one of her new models wear the first bikini ever seen at a Dallas fashion show. (The model was an unknown young woman named Raquel Welch.) Dawson had no idea how far her little shows would go. Today, with 2,000 showrooms and approximately $3.25 billion in wholesale sales, the Apparel Mart is the largest wholesale center in the world. Last year, Dawson produced 45 shows there, using more than 25 of her models for each show.

The Apparel Mart, of course, was her break. Although there was practically no local fashion photography in the Sixties- the big department stores like Neiman’s were shooting their catalogues and magazine advertisements in New York-Dawson was developing runway stars like Delpha Simpson, whom Dawson saw go-go dancing in a cage on radio disc jockey Ron Chapman’s old television show, Sump’n Else.That was Dawson’s style then: She worked mostly by the seat of her pants. Her first black male model was the maitre d’ of the Apparel Mart restaurant. She would carefully look through her children’s elementary school class pictures, trying to find cute students who could be used as child models. Dawson’s accountant and booking agent were two housewives who literally lived down the street from her.

By the mid-Sixties, the large polyester clothing manufacturers of Dallas, companies like Lorch and Nardis and Justin McCarty, began using models for a few fashion photographs. The process was very unsophisticated; the photographers simply put a large white “X” on the floor and told the models to stand there and smile. “I can remember when photographer George Dawson [Kim Dawson’s husband] had one of his pictures used in an advertisement in Vogue magazine,” says photographer Thorn Jackson, who in 1969 was just beginning his career. Now, Jackson is arguably Dallas’ best fashion photographer, traveling to Europe to shoot layouts for the best fashion magazines, but he has never forgotten his feeling when he saw that a Dallas photographer had been published in a national magazine: “I thought this might be a business after all.”

A CTUALLY, IT didn’t become much of a business until 1973, when Neiman-Marcus and Titche’s (now Joske’s) began hiring local photographers to shoot local models for full-page newspaper advertisements. They went, of course, to Dawson, and other department stores quickly followed. Soon, Dawson’s first group of print celebrities emerged-Tara Shannon (who quickly left for New York and became a world-class model); a 5-foot-9-inch woman named Pam Vickery whom Dawson calls her first great blonde star; former Miss Texas Molly Grubb; Dodie Matthias, Patsy McClenny (who later changed her name and became television personality Morgan Fairchild); and Rosie Holotik, who created an agency scandal when she posed for the cover of Playboy (fully clothed, as it turned out) and later created several broken hearts when she married former Dallas Cowboy Charlie Waters.

“It was amazing how a number of people we worked with then,” says Thorn Jackson, “were former cheerleaders who either had an ambition to be an airline stewardess or date a member of the Dallas Cowboys.”

The business was still provincial; the models were chosen if they fit the “Dallas look,” which was described by local fashion photographer Kent Barker as “healthy, girl-next-door, beautiful in a young-housewife sort of way.” The top male models of that era-Dick Selbo and Larry Harmon-were popular because they looked good in western wear. In fect, Dawson wouldn’t sign a young Mesquite girl named Jerry Hall, who later became one of the most famous New York models and Mick Jagger’s girlfriend, because she looked too tall and overwhelming for this city.

In 1974, Dawson booked more than $1 million worth of business for the first time. In that same year, Tanya Blair, who was also too tall and overwhelming to be a successful Dallas model, began her agency in a little warehouse on the edge of downtown. Two years later Sarah Norton, a former Southwest Airlines flight attendant, came in with her agency. Agencies had tried to challenge Dawson before-Peggy Taylor and Joy Wyse were two of the most prominent-but with Dawson’s monopoly at the Apparel Mart, they hardly had a fighting chance. Blair and Norton were in a dreadful position as well. They practically acted as training camps for the next group of Dawson models. “Every time I developed a good model and got her to the point where she could work well,” says Blair, “she’d come into my office and tell me she was moving over to Kim’s agency where the business was better.”

But at least Blair and Norton could survive. The reason: a burgeoning fashion catalogue market which started here in the mid-Seventies. Companies came to Dallas to take advantage of the low rates (Dallas models then made $300 a day as compared to $1,250 for New York models). The Hor-chow Collection, now with 36 catalogues a year; Sportpages, with five large catalogues a year; and Alderman Dallas, which produces 800 catalogues annually, from K Mart’s national newspaper inserts to Wal-Mart’s Christmas catalogue, all moved their operations to Dallas. Many of the photographs were standard, hand-on-the-waist shots, almost devoid of any creativity, but they brought in money. And they brought in models. Alderman’s started hiring more than 100 models a day. By 1977, the Dallas modeling era had begun.

“You might say we arrived,” says Paula Julian, for nine years a model with Kim Dawson, “but it was hardly the height of sophistication. Fashion-wise, Dallas at the time was a cheap imitation of New York and we didn’t know Europe existed. We specialized in junk mail advertisements. That’s how we made our money.”

“We were lucky to even know what modeling was,” recalls Suzanne Walker Smallwood, a Dawson model for the last 13 years. “We’d look at pictures of the models in the big New York magazines, then go look at ourselves in a mirror, and then try to figure out what we should do.”

But Smallwood, who at 5 feet 6 was turned away by Dawson twice as being too small to become a model, was typical of the kind of woman who came to dominate Dallas modeling in the late Seventies. In 1971, she graduated from high school in Gainesville, Texas, where she had been a cheerleader with one of her best friends, a dark-eyed girl named Carla Pate. Pate was already in Dallas, and asked Smallwood to come join her as a model. “We were two country bumpkins,” says Smallwood. “We didn’t even know how to put on makeup.”

Kim Dawson was immediately attracted to Pate. “The other girl I only knew as Carla Pate’s short little friend,” Dawson says. Dawson finally signed up Smallwood with Pate, and watched in amazement as the two brunettes hit paydirt. They were booked so often that they had to turn down assignments. “They were two Texas girls,” says Dawson. “Just flat-out pretty Texas girls. Who could have known they would be great models?”

More of those fresh faces followed-and they hit their stride together through the late Seventies. Although the bulk of their work came from the catalogues, they were seen in most of the local fashion ads. They had one look-clean, classic, pretty but not glamorous-and they plied it everywhere in a market mostly devoted to sportswear. “These women,” says Thorn Jackson, “were models who were alluring to men, but not intimidating to women. It wasn’t high fashion by any means, but it was the kind of look that was commercially salable.”

Carla Pate was truly a phenomenon. She first started making a lot of money in 1973, and only recently has she begun to cool off. No one in Dallas modeling has enjoyed more than a decade of such success. She was used by Sanger Harris so often that other models began referring to her as the “Sanger’s woman,” and’ when Sanger’s moved to another brunette, Joske’s picked her up. “She was the only one of us who practiced modeling,” says Paula Julian. “She would get out a magnifying glass and study the way the New York models used mascara. She had a smoky, sexy look that somehow came off as All-American.”

Pate anchored a team of such stars as Candy Fairbanks, Leighann Fisher, DeDe Seeds, Dodie Matthias, Peggy Ney, Debby Egger and Karen Jones. It was like a college sorority. They joked about the runway women and their “sucked-in cheek” look. Many of them drove expensive cars, went to the most fashionable nightspots and dated the city’s most eligible men, and they helped cultivate what Kim Dawson calls “this image that models had a magical life.”

But Dawson cultivated that image as well. She, too, had hit her peak in the modeling business. Besides her fashion models, her broadcast division was soaring. Her bookings rose past $3 million. While the national press deified models such as Cheryl Tiegs, local newspaper fashion stories began to speak of “the Dawson look.” High school girls packing photographs flooded into her office. “It was ridiculous,” says Smallwood. “Every fat little guy in town with a pretty girlfriend wanted to spend a thousand dollars on her for test pictures. Then they would all show up at Kim’s office and demand to be models.”

Dawson also kept her agency stocked with sure-fire blondes. It was, in a way, like insurance. “There was one thing,” says Daw-son, “that [New York modeling agent] Eileen Ford told me early on in this business that I have always remembered. She says that people will never forget your blondes.” It was not an unpopular view..”Always,” says Ray Payne, one of the most successful local fashion photographers, “there is going to be a need in Dallas for the great blonde.”

And so, out of Dawson’s seemingly limitless reservoir came one blonde star after another-from Candy Fairbanks to Leigh-ann Fisher to, in 1980, a young woman from Euless named Patty Smith. When Patty Smith began with Dawson in 1977, she was, as she puts it, “just another tall, gawky girl who realized I wasn’t going to make any money going to college and getting my bachelor of arts degree. Kim had me whop my hair off, and then they put all this makeup on me-all in one day. I cried my head off. I thought I looked ridiculous.”

The truth was that she was a department store’s dream, a model who could make most clothes look enticing. “She looked no different from Christie Brinkley,” says Thorn Jackson. “She was the perfect blonde, blue-eyed woman.”

Smith worked her way up Dawson’s blonde ladder and became the star as the Eighties opened. “There was no question that the only blonde in town was Patty Smith,” says Lisa Cobb, an agent for local fashion photographers. “Everywhere you looked, there she was.”

She commanded a rate of $750 a day for her work, far higher than most models in Dallas. One of the first to crack the $100,000 a year mark, she incorporated herself into a company called Patty’s Workshop, even offering a retirement plan. She was also the perfect model for Kim Dawson because she had no desire to go anywhere else. “I went to Paris to model for a week and hated it,” she says. “I was kind of spoiled by being a star in Dallas.”

Little did she know that, very soon, the definition of a star model in Dallas would begin to change.

IT WAS IRONIC that the success of classic beauties like Patty Smith helped lead in part to the erosion of Dawson’s empire. Not that Smith was to blame. It’s inconceivable that her look will ever lose value, especially here. But in the early Eighties, some of the fashion market began to move away from the Patty Smith image-and that’s when Tanya Blair came thundering into the picture.

Worldwide, the fashion look was evolving. In Europe, the catalyst for all fashion change, the designers’ newest collections demanded longer, leaner body lines. There was a trend among the top European and New York fashion photographers toward models with more dramatic faces. A model didn’t necessarily have to be pretty in the old-fashioned sense. She had to be startling, with a face that would make a fashion magazine reader pause. And she had to know how to move. No longer were photographers and art directors for department stores using the standard, flatly lit shot, where the clothes didn’t wrinkle. Now they were asking models to show the “mood” of the clothes by going so far as to roll around on the floor. The minimum height for a model was now 5 feet 8. A younger face had become more popular.

The change caught on, albeit slowly in Dallas. Neiman-Marcus, Sanger Harris and newer upscale stores like Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdale’s all asked for new faces, interesting faces, short hair, full lips and a straight nose, someone who wouldn’t be associated with the suddenly archaic “Dallas look.” In 1980, a former model named Mike Beaty moved to town and sensed that most of the male models here were outdated. He started his own agency, stressing a European look. He added women and, surprisingly, had become a major force in the market within a year.

KIM DAWSON was vulnerable; Tanya Blair knew the time was ripe for her to play her trump card. On August 29, 1980, Blair signed an agreement with the head of the second largest modeling agency in the country, John Casablancas, who runs Elite Model Management Inc. in New York City. In return for his name as part of her agency, she promised that she would provide him the best models she could find in the area.

Blair got just what she needed: influence. She could now tell models that she had a connection to New York. If they signed with her, she said, they could be picked up by Casablancas. Even more important, models from other parts of the country began to hear of Blair’s name. If they wanted to come to Dallas to work, they could sign with an agency that was already tied to Elite.

“Tanya revolutionized things,” says Paula Julian. “For the first time ever, there was not only an agent letting her girls go work out of town for a while, but an agent letting models come into town and work. Kim didn’t care about out-of-town models. She wanted the business to remain down here at home in the family. She thought she could keep it small town.”

Blair was the first to understand that the Dallas fashion market was about to go international, that as the pay for models went up to $125 an hour, more models from around the world would want to come here. “And I knew that if the local girls were going to make it,” she says, “they had better get to Europe, work for the European fashion magazines and get good tearsheets [photographs of themselves]. They had better spend time in New York and try for tearsheets there. No one was going to get hired in this town any longer with some local newspaper ads.”

Through 1981 and 1982, Blair shuttled models in and out of Dallas. Always aggressive, she personally called on clients and showed up at auditions, bringing with her photographs of models. They were different: intriguing, innovative, almost intimidating. Soon, word got around. Blair’s first star, Edie Williams (who later quit modeling to marry Dallas restaurateur Gene Street), was quickly brought to New York by Casablancas.

In 1982, Blair also solved the financial problems that had plagued her since she started by selling controlling interest of the agency to Dallas entertainment entrepreneur and old-money scion Angus Wynne, who pumped in money and reorganized the staff. “We were out to discover a small group of quality faces,” Wynne says. “We wanted to think of ourselves as a boutique compared to Kim Dawson’s supermarket.”

Although Blair’s relationship with New York’s Elite Agency quickly soured, ending in a lawsuit in which they agreed to terminate their relationship, Tanya Blair had gotten what she needed. “There was a feeling that Tanya was on the cutting edge, so to speak,” says Leslie Darden, one of Dawson’s first models to sport the newer, bold look. “There was a lot of talk back in the dressing rooms that Kim was being too loyal to her reliable girls like Patty Smith and Karen Jones, and that she wasn’t keeping up.”

Perhaps the most telling sign of how quickly things had changed in Dallas was that in 1980, a tall, thin woman with red hair and an unusual, almost harsh face came to see Kim Dawson. Her name was Jan Strim-ple. Dawson remembers that she looked at the 5-foot-10-inch Strimple and said she had an “interesting” face, but that it was doubtful she would get much work here. Strimple stayed (her husband, a golf professional, had decided to make his home in Dallas), and, as Dawson had predicted, she got little work. In 1983, she went to work a fashion show in New York, where the modeling world is always more receptive to a different face, and there she was discovered by Yves Saint Laurent. He whisked her to Paris for his shows, and by the end of the Paris season she was considered one of the top runway models in the world. When she returned triumphantly to Dallas in July 1983, almost every high-end fashion store called to use her.

But Strimple was one of the few Kim Dawson stars who got called. By then, 15 Dawson models had left for Blair’s agency, including such proven talents as Karla Kar-vas, Diane Payne (one of the top blonde catalogue models in the city), and a wispy, voluptuous redhead named Nickey Winders, who became the first model based out of Dallas to start traveling extensively to different markets. Blair also got such newcomers as Laura Jones, who had returned to Kim Dawson from her first modeling trip to Europe (after eight days on the Continent she didn’t have any modeling assignments). She went to Blair, where she soon was picked by Jordache to star in its national jeans advertisements.

Dawson’s headbook (the book showing the top models’ photographs) as of 1983, says Julian, “looked like it was made up of senior citizen models.” Indeed, for the first time, Dawson seemed to be missing the new talent. Pam Skaggs, a wide-eyed former track star from North Garland High School, showed up at the Dawson Agency with pictures shot by an amateur photographer at her church. Dawson quickly sent her away, saying that not everyone could be a model. Skaggs went to Blair, who sent her to New York for a year, then brought her back to become one of the biggest money-making brunettes in the history of Dallas modeling.

“In 1983,” says Dawson, “I looked through our headbook and realized that we didn’t have all the stars any longer. I was devastated. We still had a thriving business. That wasn’t the problem. The problem was that we didn’t have all the stars like we used to. Tanya Blair did.”

In late 1983, right after Sanger Harris booked exclusively through Tanya Blair for a large fashion shoot, Kim Dawson knew she had to do something to reverse the tide. She had to play her own trump card. After long thought, she brought into the management of her agency a young woman who, of all things, wasn’t even sure she liked the modeling business. She hired her own daughter.

LISA DAWSON wanted to be a chemist when she was in college. She also developed a liking for what she calls “the dead authors”-great writers who go mostly unread like Vladimir Nabokov and Isak Dinesen. But she had inherited her mother’s good looks, and in time became a model. When she tired of that, she worked as a stylist. Not once, however, did she think of the fashion business as a career-even when her mother called.

She took the job because she knew her mother was distracted. All through 1983, Kim Dawson’s own mother was dying. “Mom went to the hospital before work, at lunch and after work,” recalls Lisa. “When something like that happens, then agency life, especially modeling, seems so ridiculous. I knew how close she was to her mother. I knew she wasn’t hearing the complaints from all the models. Fierce family pride brought me in here more than anything else, because I understood how good we really were.”

The Dawson Agency was rife with internal problems. The top models were at odds with the Dawson booking agents over who got which assignments. The new models felt they could hardly get their feet in the door. A lot of people were demoralized. No one seemed to be communicating. “And every day when I came to work,” says Lisa, “I wondered which model would show up to tell me she was leaving for Tanya’s.”

Through 1984, Lisa Dawson led a house-cleaning of the fashion department. By April, she had brought in new booking agents. She started directing the search for new models and promoting those already on board. She was just the shot in the arm that the Dawson Agency needed. One of the first to recognize it was Blair herself. “There was no question that they started to fight again with Lisa,” she says.

Still, it took most of 1984 for the agency to stage a comeback. Rates for top models jumped again to $1,250 a day. New models continued to pour into the city. “The hunt was on,” Blair says, “for the next big star.”

Two leggy, avant-garde Dawson models who had sought greener pastures in New York suddenly discovered that Dallas was ready for their look. Leslie Darden and Laura Ballard, shuttling between the two cities, each made more than $100,000 last year.

Lisa Dawson began to push a new breed of young Texas-born models, including sultry Trish Thompson of Fort Worth; Gretchen Nooleen, a blonde who began modeling at age 14; and Sharon Summerall, a curly haired brunette with a strong, mature, European look. Summerall, a graduate of Richardson High School, broke her neck in a car wreck in December 1982. She lost 30 percent of the movement in her neck, went through a long psychological readjustment, and decided she was ready to try modeling again by May 1984. She rebuilt her confidence and then took off in the summer of 1984. Summerall was “discovered” by all thebig department stores-Neiman-Marcus,Joske’s and Sanger’s. Combined with analready strong group of catalogue models,women like Allyson Brooks and ConnieRoberson, these new stars gave the DawsonAgency a rejuvenated image. At the start of 1985, Lisa Dawson got an extra bonus whenone of Blair’s better models, Ellen Sturman,moved to the Dawson Agency after a disputewith Blair.

But Blair stayed on the offensive. In 1985, many of her models began coming back to Dallas after their first trips to Europe. They had developed a new sophistication, and they were sizzling. Sheryl Davidson, a Houston native, posed for a major Gitano swimwear advertisement. Michelle Ganeles became a lead Sanger Harris model. Courtney Wolfsberger made the cover of Seventeen magazine. Erica Walch returned from a successful stay in Paris to star in the Neiman-Marcus Christmas catalogue.

Moreover, there was no question, even among the Dawson people, that Blair’s Clarke Hanson and Pam Skaggs were the biggest one-two punch among any of the city’s models. And that made the idea of luring Hanson into the Dawson stable all the more tempting.

CLARKE HANSON was an 18-year-old art student in San Francisco when a man walked up to her on the street and asked if she would like to model. His name was Bruce Cooper, and he turned out to be the husband of Wilhelmina, who owned one of the biggest modeling agencies in New York. Inspired, Hanson went to Paris, modeled for six months, returned to New York to Ford Models and then for all practical purposes gave up her career to move to Dallas to be with her then-boyfriend, tennis professional Bill Scanlon.

When she came here in October 1982, Hanson didn’t even know there was a modeling agency in this city. But she heard about Kim Dawson, and decided to go see her.

Hanson had one of the best portfolios of photographs to come into this city, including a photo session she did with Richard Avedon that appeared in Vogue. But she never got past Dawson’s waiting room. She drove over to Blair’s agency that afternoon. In another room, without even having met Hanson, Blair looked through her book, picked up the phone, and got Hanson booked on a full-day shoot with Sanger Harris. “From there on,” says Hanson, “the work came pouring in.”

Hanson was symbolic of the new blonde look that had come to Dallas. She had mastered more “looks” than the previous blondes with their standard, girl-next-door shots. She worked in front of the camera like an actress, thinking of each photograph as a drama in which she played the leading role.

Hanson’s clients ranged from the Hor-chow catalogues to high-end fashion boutiques like The Gazebo and Alexander Julian. Her first national television commercial showed her basking in a bathing suit for La Solaire suntan lotion.

But in the spring of this year, Hanson began to suspect that the Tanya Blair Agency was not promoting her like it should. She thought they weren’t booking her with as many new clients as before, and weren’t reminding fashion photographers and the art directors who devised the fashion shots that Hanson was available.

“They had begun to take me for granted,” says Hanson. That didn’t make sense to her at all. Although in private, Hanson is strangely shy, she knows what her value is in front of the camera. She decided to arrange a secret meeting with Lisa Dawson.

OF COURSE, MODELS by nature are insecure. They never know if tomorrow will be their last day, if their clients will suddenly decide it’s time to use the latest blonde who’s arrived in town. “Models might be the most beautiful women in town, but they also have the most fragile egos,” says Paula Julian. “The minute they feel a little ignored, they go through a major psychological crisis. And they always blame it on their agency.”

The Hanson switch must be seen in context. It is not unusual for a model to change agencies, though in the competitive struggle between the agencies, Dallas has refrained from the vicious, cutthroat tactics that characterize agency wars in New York or Paris. Both Tanya Blair and Kim Dawson vow they do not “recruit” top models by making the first move and asking them to switch agencies. “Of course,” says Tanya Blair, “if a top model from another agency lets it be known she wants to move, then we’d be crazy not to say we’d love to have her. But we wait until she makes the first move.”

Throughout this past summer, business went on as usual. Tanya Blair brought in another group of young models who had done their apprenticeships in Europe. And in early July, Lisa Dawson promoted several seasoned New York models who had come to Dallas to pick up more work. There were the typical rumors of models wanting to change agencies or move to another city, but the summer stayed mostly quiet-until the last week of July, when the local modeling world broke wide open.

AFTER TANYA BLAIR exercised an option to buy back some of Angus Wynne’s interest in the company, reducing him to a minor stockholder, Wynne resigned as a company director on July 26 and announced he was beginning his own modeling agency. Five of Blair’s top bookers also resigned to go with Wynne. Immediately, some of the bookers began calling Tanya Blair models and asking them if they wanted to move with Wynne. One of the most popular bookers with Blair’s Agency, Janice Gamblin, talked with Hanson, Pam Skaggs and Nickey Winders to get them to switch-a move that would have created enormous publicity.

Blair was reeling. Never had she met with such a blatant attempt to grab her best models. She filed suit, claiming Wynne was “trying to steal everything I had created.” At first Wynne refused to be critical of Blair, simply saying he was “not satisfied with the way the agency was being run,” and wanted “an agency that was devoted to its models.” Then he filed a counter-suit against Blair, alleging defamation of character.

The sudden disarray at the Blair Agency was enough to send Hanson packing. She came in to the agency one morning, picked up all her composite photographs and her check for that week, then left without giving the slightest hint that she would not return.

On July 28, Hanson called Lisa Dawson to say she was ready to become a Dawson model. And with Hanson’s switch, the Dawson Agency shot back to the top. But how long will it stay there?

“I think the one thing that we have all learned in the last couple of years is that you must always look down the road,” says Kim Dawson. “You have to search, and then search some more, for the next great face that will sell. There’s no doubt about it. We are trying as hard as we know how to develop the next great star. The question is: Who the hell is it going to be?”

Related Articles

Hot Properties

Hot Property: An Architectural Gem You’ve Probably Driven By But Didn’t Know Was There

It's hidden in plain sight.

By Jessica Otte

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert