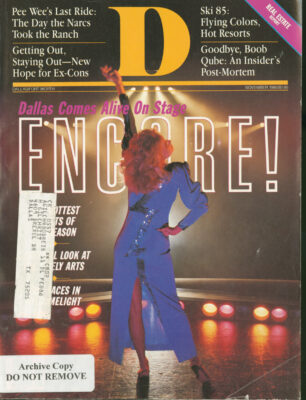

DEE HENNIGAN:

Fame’s a stage away

local theater critics claim that actress Dee Hennigan is one of the brightest stars on the Dallas stage today. That’s a heavy reputation to carry for a 23-year-old Car-rollton native who’s been out of work for the past five months and who isn’t quite sure what she’ll be doing for the next five. You might have caught Hennigan with the Shakespeare Festival of Dallas playing Miranda in The Tempest. Or you may have seen her last season at the Dallas Theater Center as Kate in Passion Play or as Constanze in Amadeus. Wherever you may see her this season, you can be sure she’s hell-bent on staying in Dallas for as long as Theater Center artistic director Adrian Hall is here.

Hennigan and her husband, actor Sean Hennigan, were working at the Alley Theater in Houston in 1982 when they heard Hall was coming to Dallas.

“It was a big deal for all the actors in Houston. We got back to Dallas as soon as we could in hopes that we could get on here and learn from him,” she recalls. While waiting for the break, Hennigan and her husband worked as waiters at Andrew’s restaurant in Addison. Hers came when she won an audition for the Theater Center play Seven Keys to Baldpate under director Peter Gerety. Although she wasn’t working directly under Hall, she says his mere presence at the Theater Center is enough to send the actors into a frenzy. Some follow him around with journals and tape recorders carefully documenting his every word, sometimes asking him to repeat himself just so their notes will be perfect. “I thought that was going a little too far. He is human and he does make mistakes,” she says. But in the next breath she admits to being more than a little in awe of the man herself.

“I love what Adrian is after, his dream of a regional theater. Artistically he has stretched me. Unlike in most regional theaters, he is a vital part in every production. He comes in at least two weeks before the show opens and watches and makes sure the play is going in the direction he wants the theater to go. What he is about is servicing the community and giving something to the people that either makes them laugh or gives them something to think about. That is exciting for me because it makes every play I work on that much more important, because you are trying to make a specific statement about this city. He’s a brilliant man, and we will stay here as long as we continue to get commitment and support. We have thought about leaving for someplace like New York, but I don’t see going someplace else and starting all over again unless the theater there could offer me what he is offering. And he’s not offering money; he’s offering work. Money has nothing to do with it.”

The actress is aware that not all her peers have as much trust and confidence in Hall as she does, but she says the ones who do are working the most consistently. “The skeptics feel like the Theater Center has developed a circle or clique of actors, and that is not true. It appears that way, I know, but I think the circle that has developed are the best actors in this town. No, we don’t have all the best actors, but Adrian is constantly looking for them.” She advises new talent to be persistent, to do anything to gain experience (especially acting for free) and to never stop beating on the casting director’s office door.

Hennigan says she acted in four shows last season, earning, in her words, about what an experienced public school teacher makes. She’s done commercial work on industrial films, radio spots and television commercials for extra money, but the competition for commercial work is even tougher than for acting jobs. “There are a lot of pretty faces in Dallas and that is what commercial work is all about,” she says. Between theater seasons Hennigan reads plays, books and theater news. “When you’re not working you’re always asking yourself, ’Why am I out of work? Should I go someplace else? How long is too long to be out of work?’”

The dormant period hasn’t been as ego-threatening to Hennigan as it could have been for a less experienced actress; in fact, she has turned down work on other Dallas stages due to what she describes as “artistic disagreements.” Hennigan says she didn’t get panicky because she knew last summer that she more than likely would begin rehearsals on a Theater Center production in October, The Skin of Our Teeth or A Christmas Carol. And for the first time in her career, she was pre-cast in a play. She says Hall asked her to perform in Life and Limb, a play he plans to direct himself in January. “But then again, none of this may happen,” she says rather matter-of-factly. “Adrian may change his mind at the last minute. You can’t expect anything because the minute you do you are going to be let down-hard.”

But if things go as planned, Hennigan can look forward to rehearsals each day from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m. for about five weeks before each play opens. “After the eight hours, you have to find a room by yourself and work out any other problems you have with your part,” she says. “It never stops. Then I go out to dinner after rehearsal with either the director or the other actors and we’ll work on it some more. When the season gets going, you are rehearsing from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. and doing a show from 7:30 p.m. to 11 p.m. Then you go out to eat with the cast after that and you don’t wake up the next day until 10 a.m.”

Because Hennigan feels so strongly about Hall’s work, as well as her own, it’s been difficult for her to ignore the bad press that seems to dog the Theater Center’s management. “It always upsets me because I’m a part of the theater. People sometimes tend to forget that the play is the thing. No matter what happens behind doors here, it is what happens out on the stage that will keep bringing the people in. Sometimes the actors get frustrated because it appears that what the general manager’s salary is is more important than what the actors’ salaries are. People forget that without us there would be no theater at all.”

STEPHEN LICKMAN:

Not content in second chair

there was always music in my family,” says Stephen Lickman, who is the only English horn player in the Dallas Symphony and the assistant to the principal oboe player. “I started out playing the flute. Then in the fifth grade it was the clarinet, and in the ninth grade I had a terrific teacher who said I needed to take up the oboe because there were too many people playing the clarinet. I thought it was wonderful to have two instruments. Then she took the clarinet away from me because someone else needed it. The year I entered Juilliard there were 36 flutes, 33 clarinets and 4 oboes. So you see the opportunities for me were a little bit better. Today, however, if I go to an audition anywhere, there are going to be 50,75 or 100 applicants for each job.”

Lickman is a Philadelphia native who lives a stone’s throw away from White Rock Lake. His house is an interesting mix of things like two black cats, a friend’s wine collection, a darkroom and photographs of airplanes. He joined the DSO back in 1975 after spending nine years teaching students at the University of West Virginia and Central Michigan University how to play the oboe. He spent nearly as much time trying to discourage them from taking on the life of a professional musician. “I finally got tired of turning out good oboe students, because the world doesn’t need any more. We make new musicians every semester, but we don’t make new orchestras.”

But when he heard about an opening for an assistant oboe player in Dallas, Lickman suddenly resigned his teaching post, won the audition and took a pay cut. “When I got here [1975], the Dallas Symphony was at its lowest,” Lickman recalls. “It was the year after it folded and the morale was quite low. The backing of the city was also incredibly low. For whatever reason, there was a lot of bad press. Since then, things have been on an incredible upswing.” Two years later, his ego not willing to endure the position of second chair, he auditioned and was named the DSO’s English horn player. “I really wanted a solo position. The English horn is a very melodic, singing instrument and there are lots of solos. It takes guts to play it, but I really couldn’t have remained second oboe. I would have gone someplace else. Some people do not want to play out front or ever be heard. They do very well. But it takes guts and a special mental attitude to play this instrument.”

Because the English horn wasn’t introduced into orchestra music until the early 1800s, not every performance calls for the instrument, so Lickman has more free time to pursue his photography business, co-piloting services and his business as a manufacturer of mouthpieces for double reed instruments. Besides those sidelines, Lickman says he spends one to two hours a day hand-carving reeds for his own instruments from reeds grown especially for musicians. One good reed will last one, perhaps two, performances. Lickman says his other pursuits help him keep the tedious reed-making work and his music in perspective.

“I think one should realize some of the other facets of life in order to produce something in music and not be one-sided. You might have had a bad performance and you might have played a wrong note, but when you take off in an airplane early in the morning, for instance, and the air is still and you do everything correctly, it is wonderful. It is a performance-type thing. You go home and feel good about the process of making things work properly; there’s nothing like it. Flying especially diminishes great and tremendous problems, because once you are way up in the air you see at once how insignificant you are in the world.”

That feeling of insignificance must have been pretty strong during the years when the DSO played to more empty chairs than full ones. But Lickman says even then he felt confident that the orchestra was on an upswing. He credits conductor Eduardo Mata with garnering support for the new symphony hall, building the orchestra’s professional image and pleasantly surprising the critics with the success of the DSO’s European tour.

Lickman says Mata improved working conditions and brought lucrative recording contracts to the DSO, but it took an event like last spring’s European tour to bring the musicians together as a true ensemble. “We grew a lot closer because we were on buses every day, checking into hotels and just learning about each other. It was very good.”

JOHNNY RENO: Horning in on tbe big time

Johnny Reno and the Sax Maniacs were playing in a Houston nightclub called Rockefellers, an old bank building renovated with a stab at art deco architecture and some neon lights. But while nothing could renovate the odor of mildew dating back to the Fifties, Reno’s fans didn’t seem to notice the smell. As usual, he had them clapping and dancing and gyrating to his sexy saxophone solos long before the first intermission. Reno looked as though he were having the time of his life-but he’ll be the first to tell you it’s a tough way to make a living.

Reno, who lives in Fort Worth, and his Maniacs are considered to be one of those regionally popular bands on the brink of making it big, thanks to years of hard work and persistence. They cut an album earlier this year, Full Blown, which was released in August, and in September signed a release for a video that should be airing on MTV now. The two efforts followed their first album, Born to Blow, which got airplay but didn’t bring the kind of financial success it takes to keep a seven-member band thriving.

Reno was back in Dallas in October for a gig at Redux, the club that replaced Tango. It was only the band’s third performance in Dallas in a year. He admits his band doesn’t play Dallas as often as it used to, simply because live music doesn’t get the kind of support it used to get in the late Seventies and early Eighties when he was playing with well-known regional groups like Stevie Ray Vaughn’s band and the Juke Jumpers. The live music clubs just don’t last in Dallas as they do in Houston and Austin and San Antonio, says Reno.

Claiming that no other regional band puts on as energetic or as rhythmic a show as he does, Reno says it’s all in the saxophone. “It’s really a physical instrument. It weighs about 20 pounds and I use it for a counterbalance a lot. I throw my body one way and throw the sax the other and I won’t fall down. Traditionally it hasn’t been used in a very physical sense. Most saxophone players are more introverted performers. It’s a prop for me as well as a musical instrument.”

Reno says that because Dallas is such a tough market to get a handle on, he and his band spend two weeks of each month traveling to cities like Washington, D.C., New York, Chicago, Baltimore and Kansas City doing one- or two-night stands in clubs that draw anywhere from 50 to 500 people a show. A performance schedule like that is critical because it helps build a following and helps promote the records, says Reno. But it also keeps him tied up with business. “I spend almost half my time on business-on the telephone setting up tours. The tours are determined by how often I think we can physically do it.”

His unique “roots rock” music is popular enough to land him shows in any of Dallas’ top live music clubs, but it doesn’t make finding places to play any easier. An agent or manager might help relieve some of the strain, but Reno says he’s not ready to turn over the reins yet. “It is a strain doing it myself because it takes away from the time I can spend on my music. That gets a bit annoying. But that is where managers come in and that is where 25 percent of your money goes. And that is 25 percent we haven’t been able to afford, or at least haven’t found anyone we thought was worth it,” Reno says.

Reno, who’s been married to video and film professional Christina Patoski for five years, says he also doesn’t want to take any backward steps in his marriage. Being on the road is tough for both of them. “We decided I would make a hard, ambitious plug at this for a couple of years and then see what happened. But this is not the lifestyle I’ll be living for the next 10 years. My goal is to be able to sell records and use the videos so that I can do a couple of tours a year in major markets and make enough money to go home and work on my music the rest of the time. Trying to make a living doing your art is difficult, and that applies to any artistic endeavor.”

PATRICIA PRICE:

Dance and discipline

Patricia Price was padding Paround barefoot, her feet slightly turned out for balance as if ready for her body to fall into a pose. Her stage was a plastic-tarped dance floor at the Dallas Black Dance Theater on the campus of Bishop College in southern Dallas-a huge, warehouse-like building with tall ceilings and terrible acoustics. Price rehearsed alone for a free performance scheduled for the following night at Lee Park.

She is a beautiful young woman, but her body does not follow the thin, lithe, delicate lines of a classical ballet dancer. At 23, she is tall and muscular, her hands and feet large and strong-looking. Physical stamina, she says, is one of her strong points. She needs it. During the dance season, Price’s day begins at 9 a.m. at the studio in the role of dancer and rehearsal director. Classes begin in the afternoon, and, during the nine-month performing season, which lasts from about March through December, rehearsals begin at 6 p.m. and often may last until midnight.

The money she earns as a dancer and rehearsal director would normally not be enough to support herself, she admits. Many of her dance friends, a number of whom graduated from the Arts Magnet High School, must hold two jobs. Price says she is lucky because her parents are still helping her out with expenses and with tuition at Texas Women’s University, where this spring she’ll continue studying dance and psychology.

Although she feels uncomfortable talking about her own dance style and comparing herself to other dancers, Price will say that she is always searching for technical perfection. She’s gone through a number of teachers in Dallas and complains that they are a “bit too laid back” and don’t demand enough effort and discipline from the dancers. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing,” she says, haltingly, “but there is not a lot of competition here for me. I think my energies and my focus are going to be strictly performance. I believe in discipline all the way. I am a perfectionist, and I feel that I take my dance a lot more seriously than many dancers here.”

Price says the way she stretches herself professionally is by attending dance workshops and special internships at well-known New York dance studios such as Alvin Ailey. Her goal is to join that company, then eventually come back to Dallas and be a leader in its relatively young dance community.

“Joining Alvin Ailey is possible. I would not want to join our own Dallas Ballet company because classical ballet is not my thing. I love ballet; I make myself take it every day because it gives me strong discipline, and every dancer needs that. But I prefer modern dance.”

Price is ambitious and optimistic about her career, but she realizes her ultimate dream may not be realized. There is always the threat of injury, and her degree in dance instruction is sort of an insurance policy against that. “I pulled a hamstring once, which is very common for dancers and very painful. The first thing that popped into my head was, ’Is this it? Is this the thing that will haunt me forever?’ The injury happened right before a performance, and it took about six months for the strength to come back. Of course the doctor said to stay off of my leg, but for a dancer there is no such thing as staying off of your legs.

“A dancer can never get toocomfortable with her level ofskill. She always has to keepstriving to be better and betterand better and the best, ifpossible. She can’t afford tostop learning.”

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.