Thomas-Booziotis

“I can do ordinary things in my sleep,” says Bill Booziotis, a designer who rejects routine the way a commuter shuns Central. “What I like is a challenge.” With partner Downing Thomas, Booziotis belongs in Dallas’ architectural Old Guard (their firm dates to 1959) but there’s nothing stodgy or cautious about them. The two are known for a free-spirited, imaginative approach to every project. Says Booziotis, “No matter how tiny or how large the project, I ask that it require a higher-than-average attention to problem-solving.”

When Booziotis says tiny, he means minuscule: He recently designed a pair of silver letter openers as a wedding gift. As for large projects, his firm has completed a remodeling of the University of Texas’ Sutton Hall-home of the UT. architecture department. Although he’s known for his imaginative flair, Booziotis insists that his satisfaction comes from “reflecting the personality of the client.” He says, “I like to make the client work as hard as we do-to really think about what they want.”

The Thomas-Booziotis practice consists of approximately one-third residential, one-third institutional (churches and schools) and one-third commercial interiors. Partner Thomas has a bent for creating contemporary buildings with deliberate historical overtones. Booziotis favors spaces that are “settings for events.” His interiors for an orthodontist’s office, for example, are riotously colorful and amusing: Instead of downplaying the cords and lines to the various dental machines, he exaggerated them in a bold tangle of thick, snaky tubes.

Concerning the direction of architecture in Dallas, Booziotis expresses both hope and misgivings: “Our city is enjoying a Renaissance-and one would hope that architects will shoulder responsibility for a wider concern than the immediate project. It becomes difficult, though, to shoulder responsibility in a developer-driven town, and so you see sites that are overbuilt and projects placed in the wrong location. An architect can have little control over these givens-at best he can mitigate the offensive parts of a program-but it’s very tough in a city where the pioneer spirit prevails.

Gary Cunningham

“The biggest problem [among architects] in Dallas is that no one wants to be a good neighbor. No one is satisfied to practice taste and restraint.” So speaks Gary Cunningham, another of the Dallas architectural world’s Young Turks. His design for the HAL building, or 14840 Landmark, is indeed modest among its glitzy neighbors at the Quorum. The small, red-brick structure is designed to disguise the fact that the ground floor is a parking garage. “It goes against the norm,” Cunningham admits. “It’s so quiet, it’s loud.” Eventually he hopes that the brick facade will be entirely covered over with ivy.

Cunningham’s work isn’t always quiet. He follows no rigid design precepts; each building is “different from the last-depending on the site, the client and how I feel. I go into every job starting over,” he says. “I have no idols. I simply try to avoid preconceptions and the latest craze.”

With the 14840 Landmark, Cunningham tried to create a plan that would make “people using it feel smart, in control. Too many buildings try to intimidate you. Here, I’ve put in windows at each end of the hall to help orient you, so you can find the elevators easily. The ceiling of the lobby is so low, you can almost reach up and touch it-which gives you more of a feeling of control.”

Another Cunningham design, an award-winning building in Longview, starts from an entirely different premise. Hidden by trees, the handsome glass structure is designed to “make people feel humbled by the forest. The entire interior is painted white to help bring the forest in.”

Cunningham has little trouble with clients who don’t go along with his ideas: “I use the ’enthusiastic stuttering’ approach,” he says. “I’ve found they’ll accept my ideas if they realize I’m committed to an idea. Besides, I tell them, “I’ve thought about this building for four months; you’ve only thought about it for 30 minutes.”

Good, Haas & Fulton

“We don’t want to do an art deco building or a Crescent echoing early 20th-century Galveston,” says Stan Haas. “We want our buildings to look like 1984. There is so much technology available today, it’s absurd to repeat old buildings.” Good, Haas & Fulton’s enviable reputation comes not from “doing old buildings” but from sensitive updates of old strip-shopping centers and designs for new ones. The firm is fluent in certain elements of the architectural language: glass tile, awnings, “orienting devices such as a clock tower.” It’s this kind of detail that helps force a facade into a smaller, friendlier scale. Color is an important design tool as well-witness the mauve, peach and terra cotta exterior of Lovers West shopping strip at Lovers Lane and Inwood Road.

Although known for their playful, sometimes whimsical touch, the partners of GH&F are serious businessmen-no studio persona or patched-sleeved jackets for them. “Good architects should be rewarded. There’s no reason why they can’t make a healthy profit. We’d like to work for the developers who are shaping Dallas, the people who are putting up Lincoln Center, INFOMART, the Anatole, the Galleria. We’d like to make more of a contribution.”

It’s likely that Good, Haas & Fulton will be noticed by the big boys soon: In their four and a half years, they have won 13 awards-for 10 buildings. For now, they will pursue the goal that is also their maxim: designing buildings that are recognized as timeless

Frank Welch & Associates

When Frank Welch was commissioned 20 years ago to design a $250,000 home, he couldn’t figure out how to spend that much. He called upon his mentor, O’Neil Ford, one of Texas’ most respected architects, and asked him what he would suggest. Ford replied, “Use lots of marble.”

Since that day. Welch has been commissioned many times to build the behemoth, the palatial, the stately home. But although he deals in size (a recent commission in Austin called for an 8,000-square-foot house), his projects tend to be nicely composed, tasteful, low-key. Like Bud Oglesby, Welch was weaned on modernism, with its emphasis on clean, functional design, its absence of ornamentation and clear relationships among elements. He believes that “materials shouldn’t be artifical-plain wallboard is better than fake paneling.” But, he says, “Few clients want modern houses. And I believe that the design must be based on the client’s dreams and aspirations. It must also be responsive to the site. Responsiveness to both client and site make for a building that is distinctive-one that’s not out of the book.”

The most successful of Welch’s houses synthesize modernism with regionalism, using indigenous materials, a studied treatment of light and formal details. Some “period designs”Southern Georgian, for example-succeed because they are sophisticated, updated recapturings of a historical style. Above all, Welch strives for a balance of light sources and spaces that are “readable.” He says, “There’s nothing more frustrating than not knowing where you are.”

Townscape

At night, the Addison Jetport serves as a beacon to pilots flying over North Dallas. By day, it is a beacon of another sort-a disciplined, stylish star among a host of lesser architectural lights. The building’s unusual shape and the rigor of its treatment rebuke the growing chaos of nostalgic styles and ungainly shapes in Far North Dallas. Its architect is Ken Siegel, founder of the 7-year-old firm called Townscape.

“I wanted an ’object-like’ building,” he explains. “The jetport was to be very formal, very disciplined, severely detailed. The grid-of tiles, glass blocks, windows and major structural elements-help give it human scale. In addition, the door looks like a door; the windows like windows.”

Ken Siegel, with partner Dick Dunavan is part of the new breed of Dallas designers. Though not committed to any one style or material, he favors blocky, gridlike structures suggestive of contemporary Japanese design. “I dont think I’d ever use reflective glass, but since every site has its own set of circumstances, I’d try for the appropriate, ’correct’ solution to that site. Still, I doubt that would ever call for reflective glass.” Siegel does have a fondness for tile: “It helps tell exactly how big the building is while making it more friendly and human.”

Townscape is conversant in the Texas vernacular as well. An example of this is his recent red brick design for Fuddrucker’s restaurant on McKinney. “Solutions vary.” Siegel says, “but they should always be refined and elegant.”

ArchiTexas

The three-man team that founded ArchiTexas-Craig Melde, Gary Skotnicki and Mark Scruggs-would welcome the challenge of a “bottom-line building-an LTV.” “We’d love to work for a developer who is big-business and well-financed,” says Skotnicki. “We could show you lots of drawings we’ve done that have never seen the light of day. Financing is such a wild game, you never know whether your design is going to be realized-unless you work for Trammell Crow.”

Young, eager and clean-cut in blue jeans dressed up with ties, the ArchiTexas trio broke into architecture by doing historical restorations-the Plaza Theater in Waxahachie, the State Theater in Austin, the Arnold House on the Wilson Block. Melde and Skotnicki worked in the City Planning Department after graduating from the University of Texas at Austin, so “it was natural for us to get into restoration work.” Perhaps their best known “adaptive reuse” project is The Lounge, the handsome art deco bar at the Inwood Theater. But a proposed restoration of a 1907 pump house on Harry Hines, which will be stripped to its stately red brick, is another promising plan for an arts center of rehearsal and recital halls. Despite its accomplishments in the area of historical restoration, ArchiTexas is not content to limit itself to small-scale, old-building redos. Trammell Crow, where are you?

OMNIPLAN

Established in 1956 as Harrell and Hamilton, OMNIPLAN is neither conventional and stuffy, nor is it poised on design’s cutting edge. At this classic, classy firm is an ongoing concern with designing buildings that, in the words of founder E.G. Hamilton, “age gracefully.” Many of them have. For example, NorthPark, Dallas’ first major shopping mall, is just as handsome and clean, and as easily adapted to its site as it was in 1965, the year it was built.

More recent OMNIPLAN buildings suggest that they, too, will stand the test of time-particularly the low-slung Blue Cross-Blue Shield buildings in Richardson, with their cascading precast concrete and tinted glass; and the First City Bank of Richardson, with alternate bands of concrete and recessed glass.

OMNIPLAN is known for its sensitive use of materials, for its attention to detail and scale and for marrying materials to appropriate designs. “We don’t use granite, for example, as if it were wallpaper,” says design director Mark Dilworth. Nor do they believe in sheathing a skyscraper in a reflective glass “skin.” “The selection of colors and materials can affect an environment tremendously,” says Hamilton.

“We have to be responsible about what we choose, because we have a responsibility not just to the client, but to the people who use the building and to the public. For us, being responsible is designing buildings that will look as good 50 years from now as they do today.”

James Pratt

James Pratt is perhaps the most cerebral architect in the city. He is our visionary thinker, an architect with an idiosyncratic style that is tough to categorize. His labyrinthic design for the Quadrangle suggests the intimacy of a medieval city; his cavernous, rough-formed Great Hall at Market Hall is expansive, aloof. “No other art really deals with space,” says Pratt, “and it’s the manipulation of space that affects people psychologically. My work is never perfect. It’s never complete. I think it’s important to leave something to the imagination. If you make [a building] too finite, others absorb it, understand it-then dismiss it.”

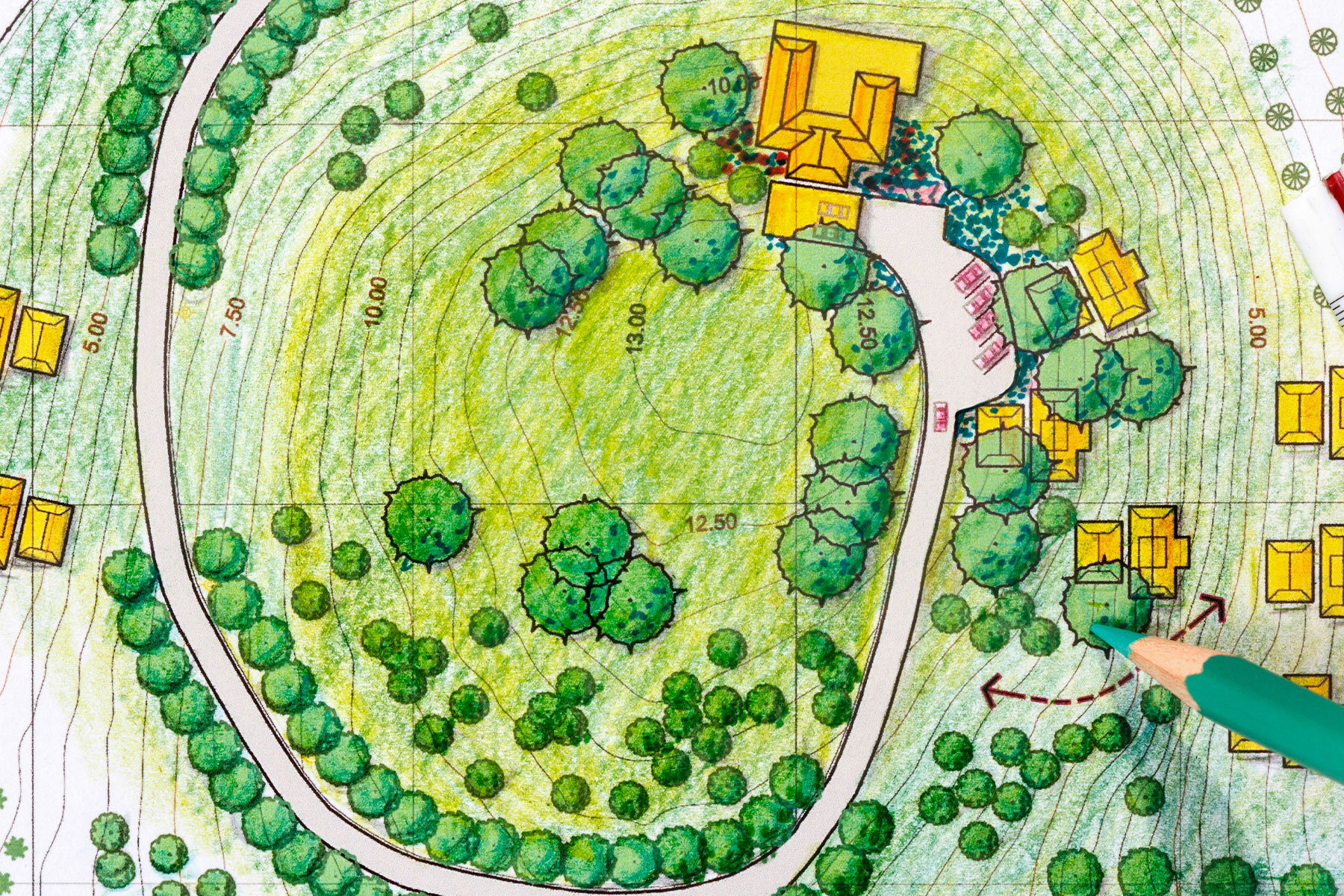

The elements of architecture that most interest him, Pratt says, are the social and the psychological. He likes to plan buildings and spaces that “bring people together in a corporate or communal togetherness.” To that end, he has just completed a plan that will help meld three disparate sections of the city: Fair Park, the downtown business district and the Baylor medical complex. Immediate plans call for building a plaza just northeast of Fair Park, extending the Fair Park esplanade, and continuing both elements beyond to Baylor. Eventually, by designing ways to “rationalize” the relationship between the three areas, Pratt thinks the city will take a shape that people can comprehend. “In Paris, people orient themselves not just by objects, but by the entire spatial layout of the city. It would be nice if that could happen here.”

Pratt has yet to design a high-rise: “I’m not so interested in size as complexity.” A grid of severe, angular brick buildings at Brookhaven College allowed him “to exercise the play of space.” What would he do with a single, big object? What he wouldn’t do is use “regimented even-floor heights. I’d try to address the down-draft problem created by large structures and the terrible energy impingement of the sun on the surface,” he says. “I’d try to develop an aesthetic that responds to these two needs. Everyone seems to build the same four sides, as though a building sits in a vacuum.”

David Dillard

Many a Dallas architect has been frustrated by a client’s demand for safe, conventional design. Not David Dillard. “When clients come to me and say, ’By golly, I want a traditional building,’ I give them a traditional building. But I’ve been influenced by Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, which advocates introducing symbols, suggestions and ambiguity in a building. Through little details that are ambiguous and suggestive, I satisfy my own need to do something of this time.”

Dillard’s penchant for complexity recently led to a Texas Society of Architects Award. His design for the Pella Showroom on Cedar Springs, once a quiet restaurant in an older, traditional building, is provocative on the interior-dazzling color, crazy angles-yet unobtrusive in its context. “I didn’t want to disturb the setting,” Dillard says, “but to give passersby a glimpse of the interior, I placed a bold neon sign just inside the door. You can catch a peek of it if you drive by.”

Other projects by this cheerfully eclectic architect bear little resemblance to the sophisticated solution for Pella Products. The Addison Fire Station, required by the mayor to be traditional and with historical overtones, is a simple red brick structure reminiscent of turn-of-the-century Texas. His Benchmark Office Building on Preston Road north of Arapaho is so skillfully blended into its residential context that it is often mistaken for a house. The structure’s gabled roofs, wood siding and subdued colors are proof that mixed zoning doesn’t have to undermine the quiet character of a neighborhood-if the architect is willing to take his cues from the surroundings.

The Oglesby Group

“I get tired of ’look-at-me’ buildings and people,” says courtly, mild-mannered Enslie ’Bud” Oglesby, the best known and most respected architect in Dallas. “We’re bombarded by ’newsworthy’ things. We’re at a point where people and things scream for attention. We need a lot more architectural equivalents for dark gray and navy blue suits.”

Oglesby’s idea of quiet architecture doesn’t translate into dark and dull. To this thorough modernist, “blue-suit” is haute couture quality-elegant, understated, with an occasional surprise.

“What’s missing from Dallas architecture,” says the man who was bred on tenets of simplicity and clean lines, “is a sense of place. Cutesy regionalism can be overdone, but when I travel, I enjoy the uniqueness of each city. When you are attracted by another part of the world, often it’s the consistency and naturalness of the setting that is pleasing. In Dallas, so many architects want to do a standout building; few are willing to create the quiet fabric of the city.

“One of the biggest challenges in Dallas is to have buildings fit their sites and to handle the intense light. How you deal with light is extremely important. How you let it enter a building, how you treat it on outside surfaces-through trellises, shutters, courtyards and recessed windows-is crucial.

“Next to that,” he says, “the rest doesn’t make much difference-whether it’s premodern, modern, postmodern or post-postmodern.”