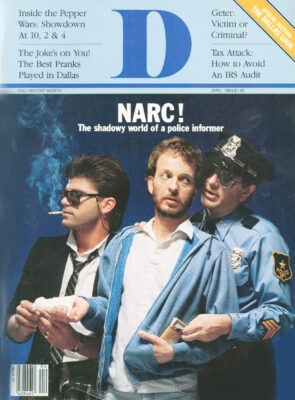

On the street, in the seamy world of thieves and dope dealers, the wiry little man was first known as Hugo but later took the name “Rabbit.” A silver-tongued man of many faces, Rabbit was an admitted outlaw by the time he was 14, but did an about-face in his early 30s and decided to join the good guys. Ironically, though his business requires anonymity, Rabbit has become Dallas’ best-known confidential police informant. Now, at 33, he has become a silent legend, described as one of the most productive and able narcotics informants to ever work the Dallas streets. In 1981, Rabbit worked with police full time to help topple the drug empire of the notorious “Z,” and last year, posing as a “meth cook” from Houston, he played a major role in a mammoth undercover operation known as the “Ron Baker multi-agency roundup,” a three-month investigation that put more than 100 Dallas narcotics dealers behind bars. These days, Rabbit has temporarily retreated from street life and is leading a quiet life working construction in a tiny Central Texas town. This is his story.

IF THE TENUOUS world of dope dealing could be compared to life in the corporate board room, it would have been a bad day at the office-a very bad day. The kind of day every confidential police informant hears stories about but hopes never to experience. On this fall day in 1981, a pencil-thin, bearded, long-haired police informant was portraying a dope dealer named Hugo. Hugo had $500 in his pocket to make a quarter-ounce drug purchase from an associate of an infamous North Texas dope dealer known as “Z.” Although dope deals are rarely routine, this speed deal with “Buckets” was considered safe enough that Hugo went alone into the office adjoining a mini-warehouse in the Harry Hines industrial district. “Buffalo,” Hugo’s undercover police partner, waited in a car outside.

Not that anybody who worked for the demented speed czar Z was to be taken routinely. Even Hugo had seen the lengths to which Z and his band of outlaws would go to protect their illicit business ventures. Hugo still can recall the day he watched Z and a companion handcuff a beautiful young woman to a bedpost and systematically kick all her teeth out, making sure that she swallowed each. The beating was a punishment because the woman had lost 2 ounces of methamphetamine powder, the substance from which Z made his livelihood.

But on this day, Hugo’s mind was preoccupied with the dope deal as he entered the office where Buckets was sitting behind a desk. After greeting Hugo, Buckets reached in a drawer and pulled out a 1-pound bag of the white powder to measure out the quarter-ounce. Suddenly Buckets pulled a pistol, spoon, rig and syringe from the desk drawer. “You’re going to shoot this with me,” Buckets said, pointing the gun at Hugo’s head. “You’re going to shoot this, or I’m going to shoot you.”

In the past, Hugo had always been able to avoid the precarious position of shooting with dopers. But this time there was no backing out. Buckets was testing Hugo. Cops nearly always back down when given the opportunity, since they’ can’t legally shoot with the dealers and then turn around and bust them. To stay alive and preserve his credibility, Hugo injected the melted-down powder into his arm. After successfully completing the drug buy, Hugo went back later that day to repay the debt to Buckets, but it was a revenge that he doesn’t care to discuss. “I don’t like people telling me what to do,” he says. “I especially don’t like anyone to point a gun at me and tell me he’s going to kill me. If a man pulls a gun on me, he’d better use it, or he’ll regret it later.”

But such bad days were rare for the cocky little man who later changed his name to Rabbit. Those who know of Rabbit’s work as an informant say he is to the street what Olivier is to the stage. Those same people say that the gangling fast-talker seems to be at his best operating in a world of con men, thieves, dope dealers, prostitutes and junkies. Sgt. Kim Sanders, a narcotics agent with the Dallas Police Department, spoke glowingly of Rabbit’s qualities and dedication in an affidavit he gave last summer for the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles.

“From the time this operation [the Ron Baker roundup] started until it ended, Rabbit was nearly always around police officers, although in an undercover capacity,” Sanders wrote. “He would make an introduction, and we made all the undercover drug buys. We were all under a great deal of pressure, because most of the individuals were violent and armed. We made an extremely large amount of drug buys, and the operation’s success is a matter of record now. Rabbit, I must say, put the officers’ safety first and helped us in a professional, methodical manner. He helped on more than just drug cases; he helped us make a case on the two individuals that tortured and murdered a Vietnamese man. He helped us find an armed robbery suspect. When Dallas police officer Ron Baker was killed, he found out which people we were dealing with might know the suspects and arranged where he could meet them. The people we made cases on were dangerous career criminals, and he knew it.

“He got very little for his efforts, but he told me his reason for helping. He said he just wanted to help society. He said if he could keep one kid from shooting dope by what he did, then he was satisfied.”

Unfortunately, all Rabbit received for three months of undercover work in the Ron Baker operation last spring was $500, 40-plus days in the Dallas County Jail and a terse letter last September from John W. Byrd, executive director of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, because Rabbit had informed while on parole.

“I want to personally deliver to you the sternest reprimand that I am capable of,” Byrd wrote. “You not only violated the letter of your agreement with the State of Texas, but you failed to heed the advice and warnings of your parole officer-the man who is responsible for assisting you in living a law-abiding life as a productive member of society. Instead, you chose to listen to and follow the guidance of someone who did not have your best interest at heart, and it very nearly cost you your freedom.

“This whole incident makes it abundantly clear that you need to be reminded that you are not a policeman. Therefore, I think it’s high time that you begin to make some realistic plans for your adjustment in the free world somewhere in between the storybook extremes of cops and robbers.

“(I do want to emphasize that the Board believes that the Texas Department of Corrections is eminently capable of housing you safely, regardless of how notorious you may have made yourself amongst the inmate population as a result of your undercover activities. I hope that you do not feel that you are insulated from the natural consequences of your actions by virtue of your reputation as a ’snitch.’)”

“Snitch” is a dirty word to an informant who takes his work seriously. It’s a term that makes Rabbit see red. Although telling on people is generally a trait frowned upon, Rabbit views informing as a noble calling. “In today’s society, your parents raise you not to tell on your brother or sister. They say, ’Don’t be a tattle-tale.’ But is that right? I’m a professional. I put a lot of pride in what I do. Informing is just like anything else. If you put forth your very best, you’ll be No. 1. There’s no excuse for being No. 2. There’s no room for No. 2. When I say I’m going to get a dope dealer, I get him.”

Informants like Rabbit are extremely valuable to narcotics agents. Not only do they help infiltrate the organizations of drug dealers and introduce undercover cops to the dealers they want to put behind bars, but they also help train inexperienced narcs to the ways of the drug world. Perhaps even more importantly, since they virtually live with the dopers, they keep a pulse on what dealers might be saying about the informit was in the fall of 1981 that he got caught up in the excitement and danger of the informant business and began to carve his reputation with the search for the notorious Z.

“Z WAS THE coldest person I’ve ever met in my life,” Rabbit says of Richard Larry Rusk, the notorious dope dealer known as Z. “I can remember sitting across from him, and hed look at me with this strange glare. It was a constant look of hate. I’d say to him, ’Z, you look like you want to kill me.’ He’d tell me he liked me. He was a nut-the weirdest person I’ve ever known.”

In the fall of 1981, police began to hear about Z, a former biker who was on the rise in the dope world. At the time, Rabbit was working off his forgery case by setting up small dope dealers for the Dallas County Sheriffs Department. Now, with the FBI, DEA, state and local police looking feverishly to find out who Z was and to locate him, Rabbit was asked to join the search for the mysterious man believed to control dozens of methamphetamine labs.

By definition, dopers are unstable personalities. They get strung-out on their own drugs, they do something stupid, and they get caught. Then, to save their own hides, they give up their former business associates when they face jail time. Z was well aware of this and had developed a drug network with a minimum of organization. Z dealt with each of his manufacturers and dealers independently, so each dealer never knew who the other associates were. But even more importantly, Z had picked up his managerial techniques from his old days as a biker; he dealt with subordinates by intimidating them. Anyone who worked for Z knew that if he informed or disobeyed, he faced certain death. (Police believe that Z may have killed as many as 35 to 40 people.)

Z was a paramilitary zealot. He was so paranoid that at times he was known to walk around carrying a hand grenade with the pin pulled, so that anyone who came close enough to kill him would also die three seconds after his hand relaxed. All of Z’s labs and houses were wired with explosives. When the labs were abandoned at night, light bulbs that contained nitroglycerine were inserted so that anyone entering the lab would be blown up the instant the lights were turned on. Refrigerators that contained dope were wired with explosives in the event that cooks decided to use the very drugs they manufactured. Z, who hated police officers with a passion, had even devised a plan to retaliate against cops in the event they raided his labs. Each of his labs had a jar of crystal laced with cyanide powder. Z was familiar enough with police procedure to know how the police field-tested the drugs that they confiscated. When police officers dropped acid on the powder to verify that it was speed, the cyanide-laced powder would produce a deadly gas.

“I think that Rabbit has always felt he wasn’t appreciated enough, so this whole thing about finding Z was tailor-made for him,” says attorney Jones. “They were telling him, ’Nobody could do it, can you?’ He said, ’Oh, sure, I can find that mother.’ I think that’s what makes Rabbit run-to be somebody. He desperately wants respect, and not just from anybody. He wants respect from people he respects.”

Rabbit did find Z. It wasn’t long before Rabbit was led by a street associate to Z’s farm at a secret location in Oklahoma just across the Texas border. “I’ll never forget that day,” says Rabbit. “I saw this spaced-out-looking guy sitting on the porch. He had long hair, a long beard and a blank stare, and when I looked at him, I couldn’t believe my eyes. Dimetri!’ I yellea out to him. Hugo! he yelled back. Here, I’d been hearing about this guy named Z, and it was this biker/dope dealer I’d known in the Sixties.”

For some reason, Z had a positive memory of Rabbit and instantly befriended him. “He was kinda funny,” says Rabbit. “If he liked you, he liked you. If he didn’t, then he’d just as soon kill you as look at you. I remember one night we stood looking up at the stars. He’d point and say, ’This can be your star, and that one is mine.’ He was going to conquer the earth and then take over Mars.”

During those few days at the Oklahoma ranch, the demented biker also told Rabbit that he owned a Bell Cobra attack helicopter, the type that was used in Vietnam. Z said that if the cops ever raided his labs, he had a plan to destroy the county courthouses in Dallas and Denton. (Although the helicopter was never found, police later raided one of Z’s warehouses and found air-to-surface missiles and napalm.) It was during those days at the ranch that Z also talked of his plan to kill 200 or 300 federal agents in one fell swoop. Z said he was going to bury several hundred pounds of explosives around his ranch that would be detonated by remote control. He would then see that the agents received a tip about a lab at the ranch. As they surrounded the ranch for a raid, he would detonate the explosives.

The rest is history. Rabbit spent several weeks leading undercover police officers to Z’s cooks and dope dealers. Rabbit only dealt with Z personally on the one occasion, and he was nowhere near the Denton KOA Campground on the day Z met a violent death. As Z left his trailer that day, he was cut down in a police crossfire. Z reportedly died with grenades in his pockets and a pistol clasped in his hand.

IN JANUARY OF last year, Rabbit got a curious phone call from attorney Lowell Jones that resulted in his returning to the street. Jones had a 17-year-old client, a kid in trouble, who was facing eight years in the state penitentiary for some small-time dope dealing. The youth was arrested in connection with a police undercover operation at Spruce High School in Pleasant Grove. Jones said that the kid came from a rich family and asked Rabbit if he knew some way his client could be helped.

Jones had quickly realized that the youth was not savvy enough to work his cases off by turning in other dope dealers. “It takes a certain amount of cold-blooded nerve to play an undercover role,” says Jones. “My client would have lost his cool.” After talking with the Dallas Police, who had offered to give the 17-year-old probation if he could turn in roughly four dealers for each of the four cases pending against him, Rabbit had an idea.

For $500 and the use of an apartment and telephone, Rabbit would help the youth work off his cases. But since Rabbit was still on parole himself, police decided that they would need the written approval of his judge, Criminal District Court Judge Kelly Loving. After securing approval from Judge Loving, Rabbit and the 17-year-old defendant rented a Balch Springs apartment, stocked it with rented furniture and put in a phone. The youth’s family put up the money for the apartment. The youth introduced Rabbit (who posed as a large-volume meth cook from Houston with an Italian surname) to many of his former drug associates. Since he was so widely known in the drug underworld as Hugo, it was now agreed that his new street name would become Rabbit.

Large-quantity transactions are the ones that so often bring down dope dealers. Many dealers are too quick to bite on big deals, since it means they won’t have to work the streets with nickel-and-dime deals. Within a short time, Rabbit had the dealers coming to him with samples of their dope.

One woman who police knew had connections with a major dope dealer kept hanging around the apartment, but she never gave Rabbit or the undercover officers any information about the high-level cook and dealer. So one day, Rabbit and one of the officers put on a show for her. Rabbit borrowed a rock ’n’ roll bus once owned by Willie Nelson and picked up the woman, telling her that they had to pick up one of his Mafia friends at a private airport in Mesquite. When Rabbit and the girl picked up the undercover officer, the officer was carrying a briefcase containing $10,000 in cash. After the officer flashed the money, it was only a matter of a few days until the dealer was attempting to get in touch with Rabbit. Before long, officers were making undercover buys right and left.

But Rabbit’s cockiness is one of the traits that so often frustrated the undercover officers he was living with. His outspoken, brash nature had created a kind of love-hate relationship between him and the officers. One night, one of the officers beat Rabbit within an inch of putting him in the hospital because of a phone call that came to the apartment. “Two officers had to pull the other officer off Rabbit,” says Jones. “Why? Picture this: The cops have been sitting next to the phone for days, waiting for this big-time dealer to call. The guy calls one night, saying that he wants to come over. Rabbit, playing hard to get, says, ’Hell no, you can’t come over. Don’t bother me,’ and slams the phone down.”

For the most part, the undercover operations were running smoothly until Dallas police officer Ron Baker was slain not too far from Rabbit’s “safe house” apartment. “After the officer was killed, everything just tightened up on the street,” Rabbit says. “Since one of our undercover officers had a van similiar to the one involved in the killing, the cops were knocking on our door. So we got busy leaning on everyone we knew to find out who did it and where they were.”

Jones says that he got a call one night from one of the officers in charge of the undercover drug operation. The officer claimed they were going to Arkansas but refused to say why. Jones says he learned later that Rabbit had helped police find Baker’s killers, who were in a house in Arkansas.

The three-month operation that ended in May of last year netted 112 suspects and 160 arrest warrants. Dallas police called the Ron Baker Roundup (named after the slain officer) the biggest drug bust in the department’s history. Rabbit was directly responsible for about 50 of the dealers arrested.

The operation was originally expected to last only a month. But Jones said that after Rabbit had ensured his client’s probation, he didn’t want to stop. “One of the officers asked me if I thought Rabbit should keep on going,” Jones recalls. “I felt it would be dangerous for Rabbit to continue. I mean, you can only play this song so many times. They [dealers] might be stupid, but they ain’t that stupid.” Jones also said that his client’s family had grown weary of supplying money for the operation. In all, he says, it cost the family $3,000 to nab enough dope dealers to ensure their son’s probation. As it turned out, Rabbit, ironically, was the one going back to jail because he had helped the police and the 17-year-old in trouble.

A MONTH LATER, on June 6, Rabbit was arrested for violating his parole. Specifically, his parole officer said the parole revocation was necessary because Rabbit had failed to submit monthly reports in April and May of 1983 (months during the Ron Baker operation), had changed his residence without prior permission of his parole officer and had acted as an informant for a law enforcement agency without permission of the parole board.

Rabbit spent the next 40 or so days in a single cell in the Dallas County Jail until he was released in August following an appeal hearing. Even Rabbit’s attorney admits that the parole board was within its rights, since he was technically supposed to secure written permission from the parole board in Austin to work with a law enforcement agency while on parole. During the appeal hearing, several police officers came to Rabbit’s defense, claiming they were unaware that the approval had to come from an authority higher than the judge who had handled his criminal case. But Rabbit’s attorney, Lowell Jones, also believes that the parole board and the police got into a power struggle over just who “owns” parolees, and Rabbit came out the loser.

Today, Rabbit is off parole. “I feel like I accomplished something. I got a lot of dealers off the street and gave the police a little more intelligence,” Rabbit says. “The community came out smelling like a rose-they got something out of it: getting the dealers off the street.

“So what have I accomplished? Nothing, really. I didn’t get no reward. I got $500, and what’s $500 going to buy me? That wouldn’t even buy my funeral. It’d barely buy the flowers. The only thing I’ve done is get into a situation of getting closer to being killed.”

Yet there is a sentimental side to the gutsy informant, a side that somehow tells him what he did was worth the risk. “I sat up one night watching a 16-year-old girl shoot her arm full of dope [and] I seen my own kid. [My daughter’s] face was painted on that kid’s face, and it liked to kill me. I broke down and started crying and thought about what I’d done to a lot of kids.”

What seems to disturb Rabbit the most about his life as a criminal is that his own association with drugs was responsible for his having to put his 5-year-old son in a foster home. “Now I realize what I’ve lost because of dope,” he says. “My little boy’s gone, and he’ll always be gone. There’s not a night that goes by that I don’t wake up and think about my little boy. I let him down, and that hurts a lot. It tears me apart.

“To deal with a kid being on drugs is hard. It’s hard to accept your child being on drugs. But you’ve got to figure out a way to handle it-to show him that you love him, to let him know he’s a somebody without drugs. Most parents don’t take the time to understand their kids. That’s what really kills me.”

Will Rabbit ever work the streets again as an informant?

Bobby Johns of the Garland Police Department spent many hours working with Rabbit on the Z busts. Johns says that Rabbit has made himself far too visible to ever be effective on the streets again. “Rabbit’s trying to make a legend of himself,” Johns says. “That’s not the way you do it in this business. He thinks he can walk on water, thinks he doesn’t drown when he’s in over his head. I know I’ll never work with him. I won’t work with a hot-dog police officer who wants to be a hero, let alone an informant. That’s what gets people killed.”

For now, Rabbit says he has retired from the street and that he’ll be content with the 9-to-5 world. He says his family would disown him if he went back to informing. Yet, listening to him, it’s obvious he misses the street and the excitement of out-conning the cons.

No sir, no more for the Rabbit. No more looking down the barrel of a gun. No more looking over his shoulder. No more nerve-racking meetings with dope dealers. No more teaching cops how to act on the streets.

Then Rabbit throws down another swig ofCoors and talks about leading another dopedealer straight to the penitentiary.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.