“This is a court of law, young man, not a court of justice.”-Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

OUTSIDE THE COURTROOM, the hot, bright television lights glare unmercifully on the prosecutor in the gray suit with thick black hair draped over his ears. The cameras are rolling, and pens are hastily scribbling on small pads as Assistant District Attorney Gerald Banks utters his fighting words.

“The NAACP is here today because it’s soliciting contributions,” he says. “As for 60 Minutes, we don’t even consider those people members of the media. They’re a propaganda outfit, not a news organization. The defense is trying to turn this into a media event.”

As the prosecutor speaks, NAACP attorney George Hairston, standing among the crowd of reporters, is listening to his competitor’s every word. “If he’s so worried about this becoming a media event, then why is he talking in front of the cameras?” Hairston mutters under his breath.

Less than a minute after the prosecutor finishes his impromptu speech, the cameras turn, and the pack of reporters huddles around a short black man with thinning gray hair who is dressed in a three-piece suit. This time, the cameras and notebooks are recording the words of Benjamin Hooks, executive director of the New York City-based NAACP.

Hooks appears angry, and he quickly responds to the unkind conclusions of the prosecutor. “I’m not here seeking publicity,” Hooks says. “I’ve been a lawyer since 1949. I’m a former public defender and a criminal court judge in Tennessee. I’m very interested in this case. A man’s liberty is at stake. A man served 14 months in prison on the flimsiest evidence I’ve ever seen. That’s why I’m here.”

Those spirited remarks were made one recent morning at the Dallas County Courthouse in a hallway outside Criminal District Court Judge John Ovard’s court. Cameras are not strangers in the hallowed halls of Dallas justice-after all, it’s through the media that many judges and lawyers get their free advertising. But this is not just another “media circus’-something very serious is going on here.

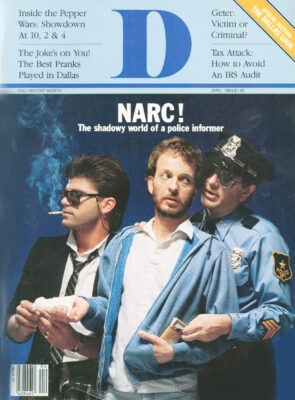

The man responsible for this media event is Lenell Geter, a 26-year-old former E-Systems Inc. engineer who was convicted of armed robbery in October 1982. Geter is a black man, a former “C” student at South Carolina State College who was recruited by the Greenville-based aircraft electronics firm from his native South Carolina. A jury found him guilty of pulling a gun from a blue gym bag on August 23, 1982, and robbing a Balch Springs Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant of $615. From the day he was arrested, Geter has maintained his innocence, claiming that he was at his desk in the Greenville E-Systems office at the time the robbery occurred.

On the surface, the Geter case seems but another grain of sand pouring through the courthouse knothole-one case among the thousands that annually travel through a criminal justice system that has become a slow-moving, inhumane and inefficient bureaucracy. Instead, the Geter case is now bigger than life. It’s been that way ever since the media began devoting a great deal of attention to the notion that sloppy police work and insensitive prosecutors convinced an all-white jury that the young engineer slipped out of his office one afternoon to commit the armed robbery. Geter’s defense team and the media have also raised questions about Geter’s harsh sentence. Although he had no prior arrest record, Geter was sentenced to life imprisonment in the state penitentiary.

Despite months of local publicity about the case and the intervention by the NAACP national office in New York City, Geter remained in a cell at the Texas Department of Corrections. Then, one Sunday evening, Dallas County justice once again went Hollywood. On December 4, television’s 60 Minutes broadcast a segment on the Geter case, portraying Geter as a victim of a criminal justice system riddled with incompetence and a disregard for the rights of the accused. (Television networks and Hollywood movie producers love to portray Texas cops as white-hatted good ol’ boys who wear aviator sunglasses and glue plastic statues of George Wallace to their dashboards.)

The CBS airing of the Geter case was the straw that broke the camel’s back; it put Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade on the defensive. Only a week or so after the segment was broadcast, Wade folded to the wishes of Geter’s defense team and agreed to retry Geter. Wade, a tough-minded man who is one of the Dallas County’s most powerful politicians, even went so far as to offer to dismiss the charges altogether if Geter passed a polygraph test-an offer that Geter declined. The last time Wade made such a generous offer was about five years ago when a number of defendants in a drug case alleged that police officers had planted the dope.

Wade became so concerned with the Geter case that he assigned two assistant district attorneys and two investigators to retry it. At this writing, the trial is scheduled to begin April 9. Ironically, the defendant has taken the offensive and is challenging the methods, credibility and power of the Dallas County district attorney’s office. Perry Mason probably would have called it a case of the accuser becoming the accused.

“About 40 million people saw 60 Minutes and believed the version they saw,” says Gerald Banks, one of the two prosecutors assigned to retry Geter. “We think it was a perverted version, but many people in the community may think that’s what it’s really like. There’s no question about it-it hurt many people’s confidence in our criminal justice system. Mr. Wade is making an effort to restore people’s faith in the law. Hell, he didn’t have to give anybody a new trial.” (Banks has since resigned to pursue his private practice.)

THE ANNALS OF crime are stuffed with “Jekyll and Hyde” villains who have led lives of respectability mixed with iniqui-tousness. Men who have devoted their lives to the study of psychology repeatedly remind us that the criminal mind is a book that can’t be told by its cover.

On the other hand, it seems preposterous that a mechanical engineer earning $24,000 annually would have either the method or motive to knock over a 7-Eleven, Taco Bell or Kentucky Fried Chicken after putting in his eight hours at the drafting table. But under Texas law, a prosecutor needn’t bother himself with such thoughts, because he isn’t required to show a motive to convict a man suspected of committing an armed robbery.

Still, prosecutors are theoretically duty-bound to see that justice is done, even if it means losing an important case and letting a man go free. While most attorneys would rarely accuse prosecutors of intentionally putting innocent men in jail, they often criticize them for moving ahead with cases in which the evidence is not so clear-cut. But many good prosecutors rarely think beyond the courtroom; they know juries well, and they know what it takes to convince 12 courtroom novices that a suspect is guilty.

This is what happened to Geter, according to one of hit attorneys, Edwin Sigel. “Lenell was an innocent guy who just got grabbed up in a net,” Sigel says. “The prosecution had no idea who they were trying. Many of these prosecutors are young and have no experience at representing innocent people. They’re too busy shuffling bodies, clearing people out of the [county] jail. What happens is that when you see an innocent guy, nobody recognizes him.

“When I first met Lenell, I really didn’t know whether he was a criminal. He doesn’t look like a criminal, and he doesn’t talk like one. But when I first explained those feelings to Randy [Isenberg, the prosecutor] before the first trial, he told me: ’He’s a con man. He’s good for these robberies, and we’re going to bury him.’ By the weekend before the trial, I thought he was innocent, but after they started presenting the evidence, I knew he was innocent. It was like a snowball going downhill, and nobody would stop it.”

Prosecutor Banks, on the other hand, says that men often go to prison on less evidence. “Don’t forget that five eyewitnesses identified Geter as the robber,” Banks says. “If I thought he was innocent, I wouldn’t be retrying him. This is a typical case. As for his alibi witnesses, they all knew him as a good worker, a quiet guy who didn’t holler “discrimination.” He just did his job. I don’t think any of them would outright lie, but I think they subconsciously force themselves to remember him being at work. Because for Geter to do something like this just doesn’t compute.”

There’s probably merit in what both the defense and prosecution have to say. In the real world of the criminal justice system, Geter is a rarity. Anyone who spends a little time around the Dallas County criminal courts quickly realizes that justice, in most cases, is tantamount to the best plea-bargain deal a defendant’s lawyer can make with the prosecutor. Anybody who wants to do battle in the courtroom has to first consider the fact that Henry Wade’s boys don’t lose very often.

Here are a few facts for any skeptics: During 1983, Dallas County courts disposed of 14,425 felony cases. Of that total, 10,735 were settled by guilty pleas on the part of defendants. That’s roughly three of every four cases cleared by the felony courts. In Dallas County last year, there were only 1,116 trials: 712 by jury and 404 before a judge. In the instance of jury trials, prosecutors secured convictions in 624 of the 712 trials, an 88 percent conviction rate. In 134 of those convictions, defendants received life sentences.

Those facts illustrate the awesome power that is vested in the men who work for Henry Wade. Many legal scholars would even go so far as to claim that the district attorney has unseen powers because so much of our county’s justice is based on backroom deals rather than jury trials. In jury trials, police investigations are placed under closer scrutiny; such things as forced confessions or improper investigative techniques come to light more often through testimony.

SPRINKLED GENEROUSLY throughout the Geter case are circumstances, questions and contradictions that will hopefully be cleared up in his second trial. For example:

●Although five witnesses identified Geter from photo lineups and in court as the man who robbed the Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant in August, about eight of his co-workers said they saw Geter at work on the day of the crime. Not one of the co-workers, however, could state unequivocally that Geter was at the Greenville E-Systems office at the time of the robbery (between 3 and 3:30 p.m.) The robbery occurred in Balch Springs, which is about a 45-to 50-minute drive from Geter’s office.

As is often the case, the prosecution has no physical evidence linking him to the crime: no gun, no fingerprints and none of the clothing that Geter supposedly wore during the robbery.

● The facts strongly suggest that Geter and his defense attorney, Edwin Sigel, were not prepared to go to trial. Even though the judge was within his legal rights in going ahead with the October 18, 1982, trial (the statutes say court-appointed attorneys must be given at least 10 days to prepare a defense), many attorneys claim that judges are liberal in giving defendants extra time to prepare their cases, especially when a defense attorney flatly states he isn’t ready.

Geter’s parents paid their son’s first attorney a $1,500 retainer fee but later fired the attorney after they became dissatisfied. Geter then signed an affidavit stating that he was indigent, and Sigel was appointed in October-two to three weeks before the trial. However, Sigel claims that he was informed of the trial date only four days in advance, and that he and Geter couldn’t communicate over the jail phone because Geter believed that he was being tape-recorded.

●Were police tactics in the Geter investigation kosher? Defense attorneys say no and point to a “big lie” told by Lt. James M. Fortenberry, a 17-year veteran detective with the Greenville Police Department. According to Sigel, that “big lie” came when Fortenberry formulated a theory that Geter had moved to Texas from South Carolina as a member of a six-man band of black criminals who were committing strings of armed robberies in the Dallas area. Sigel also contends that Fortenberry lied when he testified in the punishment phase of Geter’s trial about his contact with a sheriff in South Carolina, Geter’s home state. According to his testimony, the sheriff told Fortenberry: “Oh, Geter’s a bad guy. . .I know Geter; he’s a bad, bad character.” Sigel claims that post-trial interviews with the sheriff indicate that the sheriff never said any of the things Fortenberry had testified to.

Prosecutor Banks says he is happy with the work of the police officers, and he denies allegations by the NAACP that Geter was the victim of racism. “I guess you should put a white man in a police lineup if the people who were robbed tell you a black man committed the robbery,” he says.

●Why did Geter refuse to sign an application for probation even after the presiding judge and his own attorney repeatedly advised him that if he were convicted of the robbery, the jury would not even be able to consider probation as a punishment? That decision on his part meant that he would go to the penitentiary if he was convicted.

●Why didn’t Geter live up to the deal that his attorneys made with Wade and submit to a polygraph? Geter’s attorneys say their client is a nervous individual-a “passive-aggressive”-and that he stands to lose more by taking it. Geter’s attorneys say that their client has passed three defense-commissioned polygraphs, but prosecutor Banks says they are unacceptable for a variety of reasons. Banks is quick to point out that even if Geter should fail the test, the results would not be admissible in a Texas court.

GETER’S SECOND TRIAL, scheduled for April 9, is slated to be the most-publicized in recent Dallas history. If Wade and company have their way, not only will Geter be on trial, but so will 60 Minutes.

Judge Ovard has approved a prosecution request to subpoena all the other tapes that the network news program made (commonly called “out-takes”) and has even subpoenaed newsman Morley Safer. Banks claims the prosecution just wants to know if CBS researchers might have developed any new information. But it’s quite clear that the district attorney’s office is very upset that its image might have been tarnished. “I think they raped us,” says Banks. “We know they interviewed a number of other people, including our investigator and the five eyewitnesses who identified him as the robber. Why weren’t any of those interviews shown?”

With the exception of saying that they will do what they can to avoid producing the tapes or Safer, 60 Minutes officials aren’t commenting on the recent events. At the time of this writing, it’s unknown if the subpoenas will ever be officially served. For example, if Safer is required to appear, he must be subpoenaed by a judge in New York.

Even though the district attorney’s office has reinvestigated Geter extensively, the state’s case against Geter likely will include much of the same evidence and many of the same witnesses. This time, the defense will be fully prepared (it subpoenaed 55 witnesses for Geter’s pre-trial) and the public should be able to feel a bit more confident that the verdict will be a just one. But as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. implies in his advice to a young law student, the final decision will rest in the hands of the 12 people who will make their decision solely on what they hear in the courtroom.

Whether one believes Geter is innocent or guilty, victim or criminal, his legal experiences illustrate that the criminal justice system does have its safeguards. Yet, those safeguards sometimes need prodding-in this case from two long-standing adversaries of the system: the NAACP and the media.

When you consider the alternatives, maybe an occasional “media circus” isn’t too much of a burden for us to bear.

Related Articles

Restaurant Openings and Closings

Try the Whole Roast Pig at This Mexico City-Inspired New Taco Spot

Its founders may have a fine-dining pedigree working for Julian Barsotti, but Tacos El Metro is a casual spot with tacos, tortas, and killer beans.

Visual Arts

Raychael Stine’s Technicolor Return to Dallas

The painter's exhibition at Cris Worley Fine Arts is a reflection of her training at UTD—and of Dallas' golden period of art.

By Richard Patterson

Dallas History

Tales from the Dallas History Archives: Scenes from 1949, When the Mob Ruled Dallas

In 1949, streetcars still roamed Dallas' streets, the Adolphus Hotel towered over its neighbors downtown, the State Fair was still segregated, and Benny Binion wanted his money.