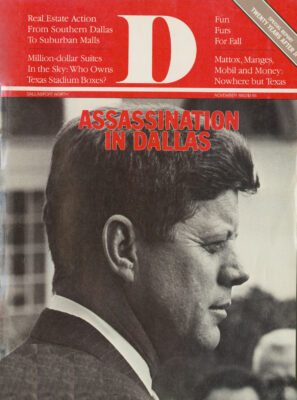

AFTER NOVEMBER 22, 1963, it seemed that Dallas was doomed to live forever under the curse of the Kennedy assassination. Since then, Americans have witnessed the murders of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy as well as the attempted assassinations of Gov. George Wallace and President Reagan. These unspeakable events made us realize that tragedy can happen anywhere.

Still, there was something about the first in this string of national sorrows that seemed to single out Dallas for suffering so comprehensive that it had to be seen as the result of a fatal flaw in our character. Some people called us Philistines, inflicted with a vulgar love of money and untempered by a taste for art or tolerance for views different from our own. Others charged that our greed was grounded in piety and smug self-satisfaction. Willie Morris wrote in North Toward Home that Dallas was a “city of bank vaults and choirs.”

Of course, there were grains of truth in these accusations, but they were exaggerated into a grotesque caricature of the way we really were in the early Sixties. For the most part, Dallas in those days was a city of nearly 700,000 people who had moved here from small towns in Texas or other cities in the South.

These people were seekers and strivers who, Methodist or not, followed the admonition of John Wesley to “work as hard as you can, save as much as you can, give as much as you can.” Whatever wealth had been accumulated was still in the hands of the first generation, which believed in churches and hospitals but not much in museums or universities.

A Fortune magazine article written during the aftermath of the assassination stated, “In general, Dallasites looked upon their city as the center of the universe.” The story quoted local writer John William Rogers as saying, “Dallas as a city never sees any but its own newspapers and follows nothing but its own activities… its life is lived in terms of itself.” Kennedy’s trip to Dallas shattered all that.

There had been premonitions of trouble. Just a month before, U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson had been hit in the head by pickets who were demonstrating outside the Dallas Convention Center in protest of U.S. involvement in the United Nations. And during the presidential campaign of 1960, Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson were mobbed and booed as they tried to enter the Adolphus Hotel. The crowd included not only the usual downtown street people, but also several Junior Leaguers who were celebrating Republican “Tag Day.” Their association with the mob scene was accidental, but it hurt Dallas nonetheless.

There had been considerable debate about what to do for Kennedy on November 22. Naturally, local Democrats wanted to host the arrangements for him, but the word from the White House was that the president wanted some exposure to the fat cats, many of whom had favored Nixon in 1960.

After much squabbling, it was decided that the Dallas Citizens Council, the Dallas Assembly and the Graduate Research Center of the Southwest would host a luncheon at the Trade Mart. The luncheon sponsors were the city fathers of Dallas, and the knowledge that they were finally taking charge of the plans for Kennedy’s visit was reassuring. But their leadership would be severely tested by the events of the next four days.

The assassination turned Dallas against itself in an agony of self-accusation. There were public meetings to ponder our civic culpability. Dallas leaders gathered in homes to grieve quietly and to discuss how we could heal ourselves as a city.

But the city’s reputation suffered terribly. As Rabbi Levi Olan, a local religious leader, recently said, “Every time the name Dallas was mentioned, it represented in the minds of people all over the world that this was the place where they killed Kennedy. Dallas got a bad name. It took a long time to overcome.”

In that 1964 Fortune article, Olan charged that “the business leadership is largely interested in rebuilding the image of Dallas, not in making fundamental changes.” But, in fact, fundamental changes did occur. Under the in- tense pressure that followed the assassination, there emerged a new generation of leaders who broadened their vision and broke out of the insularity that had made the radical right not only possible but fashionable here. Suddenly, it was okay again to be a Democrat in Dallas, where it hadn’t been during the Eisenhower years. Erik Jonsson, a Republican, was elected mayor, so the city kept a foot firmly in both camps while re-entering the national mainstream.

Problems persisted in public education, social agencies and funding for the arts and universities, but a fresh attack was launched on all of these fronts. Dallas began to look outward with the construction of D/FW airport and the new City Hall, and the age of expansion began. The generation that came to the fore to put the pieces back together after the assassination laid the groundwork for the ascendancy that Dallas enjoys today.

But, more importantly, the atmosphere in Dallas changed. We opened ourselves up to the world, both to its criticism and to its bracing opportunities for growth. By enduring our suffering in the wake of the assassination, we learned the habit of self-criticism and the discipline of dissent. Out of turmoil came a new style of public life. We became more complex and less complacent. As Dr. W.B.J. Martin, former pastor of First Community Church of Dallas, says, “We’re a lot more civilized.”

Friday, November 22, 1963, changed many lives, including journalist Hugh Aynesworth’s. His account of that day leads our observance of the 20th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination. Our stories begin on page 102.

We are proud to announce that D Magazinewill be publishing the Official Guide to the1984 Republican National Convention. It’ll bethe publication to have if you want to knowwhere to dine, drink, jog, shop, see good art orplay the political horses while you’re in Dallas.It’ll also feature profiles of important Republicans and a perspective on the Reagan years aswell as the essential political aspects of theDallas/Fort Worth area. The guide will begeared to delegates, media, visitors, public officials and local citizens, all of whom we believe will want a copy to keep as a reminder ofthis historic occasion. Dave Fox, chairman ofthe GOP Welcoming Committee, says that thesummer of 1984 belongs to Dallas. We at Dwant to help make that happen.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Restaurant Reviews

You Need to Try the Sunday Brunch at Petra and the Beast

Expect savory buns, super-tender fried chicken, slabs of smoked pork, and light cocktails at the acclaimed restaurant’s new Sunday brunch service.

Arts & Entertainment

DIFF Preview: How the Death of Its Subject Caused a Dallas Documentary to Shift Gears

Michael Rowley’s Racing Mister Fahrenheit, about the late Dallas businessman Bobby Haas, will premiere during the eight-day Dallas International Film Festival.

By Todd Jorgenson

Commercial Real Estate

What’s Behind DFW’s Outpatient Building Squeeze?

High costs and high demand have tenants looking in increasingly creative places.

By Will Maddox