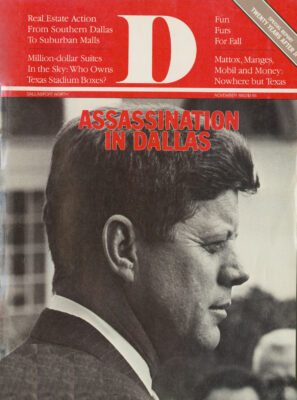

AFTER 20 years of debate and dead ends, the question of who shot Kennedy is still very much alive. Conspiracy theorists point to numerous loose ends, unanswered questions, obvious deceptions. Was Lee Harvey Oswald a Soviet spy? Did he double-cross the CIA? Was he the pawn of organized crime? Did he act alone, or did he act at all? Nothing has fueled the assassination controversy more than the paradox of Oswald, the ex-Marine and avowed Marxist. He didn’t fit the mold of a conspirator to be trusted with such an awesome task as killing a president. Yet he seemed too much of a dolt to have done it alone. He is the paramount mystery, and because of executioner Jack Ruby, he will remain so forever.

Critics have doubted the lone-assassin theory since the assassination. Their questions have not only remained unanswered, they have proliferated. The more we learn about the events of November 22, 1963, the less we know about what actually happened.

Private researchers with their noses to the conspiracy trail as well as sanctioned government bodies-notably, the U.S. House Assassinations Committee-have poked the 1964 Warren Commission Report full of holes. G. Robert Blakey, chief counsel for the 1978-79 House probe, has said that the Warren Commission was “fundamentally wrong” in stating that Lee Harvey Oswald was solely responsible for shooting Kennedy. By not telling the American public that ” ’We’re not sure whether others were involved,’ ” Blakey believes, “the Warren Commission let into our society a kind of poison that has run through the body politic ever since.”

If the ensuing years have cast doubts on our government’s methods and motives in investigating Kennedy’s death, they have also cast the world in a new light. Global intelligence operations have come under the glare of the Freedom of Information Act. We know things now that we never dreamed of in 1963. Who could have foreseen that the Soviet Union would one day be accused of plotting to kill the pope, using a terrorist from Turkey as a hired gun? Does Soviet complicity in the assassination of a president now seem so preposterous?

For that matter, who knew in 1963 that our own CIA had orchestrated international assassination schemes? One member of the Warren Commission, former CIA Director Allen Dulles, knew of the death plots, but he never spoke up. Why did Dulles remain silent when it was obvious that such a formidable target as Fidel Castro might have retaliated in Dallas?

Yet, despite the doubts, even Blakey’s House Committee couldn’t find sufficient evidence to name any conspirators other than Oswald. For reasons not very compatible with information uncovered by the committee, the panel ruled out the possibility of the Soviet or Cuban governments being involved. The panel didn’t, however, ignore the “possibility” of conspiratorial involvement by individual members of organized crime or anti-Castro groups-in-cluding some rogue elements of American intelligence.

It’s difficult to understand why, with the tremendous resources of two heavily financed, government-backed probes, the issue of who killed Kennedy has never been put to rest. But the mystery-at least, in many minds-lingers.

Russian Riddles

In 1959, Lee Harvey Oswald traveled to Russia in a self-imposed exile that lasted more than two years. The U.S. State Department paid his way back. Two days after Oswald’s return-tickets were issued in June 1962, Soviet KGB Officer Yuri Nosenko first talked of defecting to the CIA.

Two months after the Kennedy assassination, Nosenko defected to the United States, claiming that he “personally superintended” the KGB file on Oswald in Russia. Nosenko insisted that Soviet police considered Oswald unstable. The KGB, he maintained, never debriefed the American upon his entry to Russia and never dreamed of using him as an agent.

In 1964, the FBI found what it believed was confirmation of Nosenko’s story from a Soviet diplomat in New York who was then a highly trusted double agent. But in 1980, the FBI re-evaluated its source (code-named “Fedora”) and found him to be a triple agent with allegiances still in the Soviet Union. Fedora returned permanently to Russia before the FBI could complete its in-house probe.

There are other discrepancies that suggest that Oswald may have meant more to the Russians than Nosenko avowed. One is the dubious authenticity of Oswald’s “historic diary’- found among his possessions after the assassination. The diary contains the only written information about Oswald from January 1960 to March 1961, that time he spent in the Soviet Union. In 1978, handwriting experts told the House Assassinations Committee that the diary was written by Oswald, but that it was written on the same paper and in a continuous pattern in one or two sittings. Yet, the possibility of a forgery is substantiated by dates and events described in the diary that occurred well after the time in which Oswald supposedly wrote them. Oswald’s wife, Marina, testified that he brought the diary with him when he returned to the United States, making it seem feasible that if it was a fabrication, it had been concocted in Russia.

Did Oswald return to the United States from Russia in 1962 as a “sleeper,” a Soviet agent provocateur? Why did he refuse an FBI request within a month of his arrival to take a polygraph test to determine whether he had dealt with Soviet intelligence forces? Why didn’t the FBI disclose the incident to the Warren Commission two years later?

The polygraph test was requested by FBI agent John W. Fain during an interview with Oswald in Fort Worth. Despite being questioned in detail by commission members Gerald Ford and Allen Dulles, Fain never revealed his exchange with Oswald concerning the lie detector test. He did reveal that after a two-hour interview, Oswald promised to notify Fain if he was contacted by Soviet agents in this country “under suspicious circumstances or otherwise.” After the assassination, the FBI stated consistently that Oswald never reported any such contact.

In 1975, however, after a 12-year silence, the FBI was forced to acknowledge that Oswald did contact its Dallas office several weeks before the assassination. According to the FBI, he left a threatening note but was not arrested or even questioned. Nancy Fenner, then a secretary in the FBI office, recalled that, in the note, Oswald threatened to “blow up” the place if FBI agent James Hosty continued “bothering” his wife. Hours after Ruby killed Oswald, the note was secretly destroyed. Hosty later claimed that he was ordered not to mention the note by the Dallas agent-in-charge, J. Gordon Shank-lin. In 1975, Shanklin testified that he could not remember the incident.

At about the same time the note was destroyed, another disappearing act involving the FBI occurred. In a search of Oswald’s old Marine sea bag soon after the assassination, Dallas police detective Gus Rose found a Minox camera-a miniature piece of equipment often used for espionage work-loaded with film. The German-made camera and film were listed in the Dallas police inventory and in an initial FBI log.

After the property was delivered to the FBI laboratory in Washington, D.C., however, the listing was changed to read “Minox light meter.” The FBI tried unsuccessfully to pressure Rose into reporting that he had found a light meter, not a camera. Later, the FBI entered into its records the existence of a Minox camera-claiming that it was not Oswald’s but was the property of someone in the Irving house in which Oswald’s sea bag had been stored. In 1978, under a Freedom of Information Act request, the FBI released 25 photographs developed from two rolls of Minox camera film found among Oswald’s possessions 15 years earlier. More than 20 prints from one roll showed civilian scenes apparently taken in Europe; five shots from the other roll depicted military locations either in the Far East or in Central America.

Even more disturbing is information that has been brought out regarding a meeting between Oswald and the Soviet KGB officer for assassination and sabotage in the Western Hemisphere, Valeriy Kostikov, two months before Kennedy’s death. The CIA apparently monitored contact between Oswald and the Soviet Embassy in Mexico City during September 1963.

The public wasn’t made aware of the meeting and the nature of Kostikov’s KGB role until 12 years later. When the Senate Intelligence Committee declassified a CIA account of Oswald’s Mexico City contacts in 1976, it charged that the FBI’s Soviet experts in Washington in 1963 had information about Kostikov’s mission. The committee found it “most surprising” that the FBI “did not intensify their efforts in the Oswald case” after being informed that Oswald had met with Kostikov.

The final report of the House Assassinations Committee in 1979 mentioned Kostikov only once in its 307 pages concerning the Kennedy killing. It stated that Oswald met with “an individual possibly identified as Soviet Consul Kostikov” in Mexico City, but made no mention of his ominous KGB role. A 300-page report published by the committee, entitled “Lee Harvey Oswald, the CIA and Mexico City,” remains classified.

Despite the official silences, it appears that former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover harbored suspicions about Oswald in Mexico City-after the fact. Early in 1964, Hoover dispatched an undercover agent, Morris Childs, to Cuba to interview Castro. Masquerading as a member of the U.S. Communist Party, Childs (code-named “Solo”) returned with word that Castro had accused Oswald, while in Mexico City, of vowing in the presence of Cuban Consulate officials to assassinate Kennedy. The theory is that the Cubans would have relayed such a threat to the Russians, and, after learning of Oswald’s remark, the Soviets’ KGB agent in charge of assassination and sabotage agreed to talk with Oswald.

“First of all, Oswald said [to the Cubans] that he wanted to do it [kill Kennedy],” former FBI agent James Hosty said. “Then he met with Kostikov. And then he did it [eight weeks later]. Now, that doesn’t prove anything. But it sure doesn’t look good.”

Links with Organized Crime

As early as fall 1962, Mafia overlords were rumored to have muttered threats on Kennedy’s life. Their hatred of Kennedy drew a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they were angered by Kennedy’s botched Bay of Pigs invasion during spring 1962. Mafia leaders had suffered when Castro came to power and had closed their gambling casinos in Cuba. They felt betrayed when Kennedy let Castro off the hook.

Most bitter was Santos Trafficante, the La Cosa Nostra leader in Florida and the mob’s chief liaison to criminal figures within the Cuban exile community. Not only had Traf-ficante lost considerable gambling properties in Havana, but he also was imprisoned by the Cuban revolutionary government. After his release from prison, Trafficante recruited Cuban nationals to assist in the CIA’s efforts to assassinate Castro. In September 1962, the FBI received word through an informant, José Aleman, that Trafficante had put out the word that Kennedy was “going to be hit.”

Other irate mobsters were potential victims of Robert Kennedy’s war on organized crime. One prime target, James Hoffa, was facing a prison sentence when he discussed plans to kill the president’s brother, according to tape recordings made by Teamsters officer Grady Par-tin. One of Hoffe’s plans, it states, was to shoot Robert Kennedy using the telescopic sight of a rifle as he rode in a convertible in a Southern city.

A friend of Hoffa’s and Trafficante’s, New Orleans boss Carlos Marcello, had tasted the vengeance of RFK’s crackdown on crime. He had been snatched from his home streets by federal agents, then deported to Guatemala. Marcello had ample reason to want to bring the Kennedys down, and he reportedly favored going after the president, citing an old Sicilian adage that “to kill a rooster you don’t cut off the tail, you cut off the head.” Marcello spoke of using “some nut” to take the blame and to avoid any suspicion of a Mafia hit.

One of Marcello’s men in New Orleans was Charles “Dutz” Murret, Oswald’s uncle. In April 1963, Oswald stayed at the Murrets’ home when he moved to New Orleans to look for a job. Conspiracy theorists have pointed to Mur-ret as Oswald’s conduit to highly placed figures in brganized crime.

Cuban Connections

The five months that Oswald spent in New Orleans were marked by his unusual ambivalence toward Castro. One day, he’d be passing out pro-Castro leaflets; another day would find him begging to join the CIA-backed anti-Castro forces training nearby. In a way, Oswald’s actions reflected the Kennedy administration’s contradictory stance toward Cuba throughout 1963.

Shortly before Oswald moved to New Orleans, Cuban refugees were warned that Kennedy would no longer tolerate the refugees’ use of the United States as a base for Cuban attacks. The FBI stepped up its raids on the exile guerrilla training camps. Dr. Jose Cardona of Miami resigned as president of the anti-Castro Cuban Revolutionary Council, claiming that Kennedy had promised a new invasion of Cuba after the Bay of Pigs.

By mid-June 1963, the Kennedy administration reversed gears and gave the CIA permission to revive a “secret war” of sabotage against Cuba. Although Kennedy didn’t endorse the idea of assassinating Castro, the CIA rekindled its hit-plans on the sly. But by September, the pendulum had swung back again.

Oswald showed an interest in joining the anti-Castro forces. In July, he visited New Orleans leader Ernesto Rodriguez Jr. Rodriguez said that Oswald told him that he “was interested in the Cubans and the Cuban [anti-Castro] cause, and that he wanted to be able to help-that he was an ex-Marine.” Oswald was “aware that there was a training camp across the lake from us, north of Lake Pontchartrain, and he wanted to get into that,” Rodriguez said.

But at the same time, Oswald joined the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), a pro-Castro organization headquartered in New York. Oswald wrote FPCC national director Vincent T. Lee in New York, stating that he had rented an office for a one-man chapter in New Orleans, but that it “was promptly closed three days later for some obscure reason by the renters.” To this day, no one knows where that office was located.

Oswald was arrested 10 days later while distributing pro-Castro FPCC literature in downtown New Orleans. He was charged with disturbing the peace during a scuffle with anti-Castro Cuban exile Carlos Bringuier. Ironically, Oswald had met Bringuier a few days earlier regarding his desire to train Cuban exiles.

From his jail cell, Oswald told a New Orleans police intelligence officer that he “was desirous of seeing an agent [of the FBI] and supplying to him information with regard to his activities with the FPCC in New Orleans,” according to an FBI report suppressed from the public until 1977. Agent John Quigley talked to Oswald in his cell for about 90 minutes, then left with some of his FPCC literature. The address, “FPCC, 544 Camp Street, New Orleans, La.,” was stamped on the last page of one of the pamphlets that Quigley was given. A few days later, an FBI informant sent a second copy with the same rubber-stamped address.

The incongruity of Oswald staging his pro-Castro show out of 544 Camp must have raised an eyebrow or two at the FBI. Agents knew of another tenant in the shoddy three-story building: W. Guy Banister, former Chicago FBI chief and rabid anti-Communist. Banister’s “private detective agency” was actually a cover for his role as liaison between the CIA and Cuban anti-Castro exiles.

The FBI told the Warren Commission that it was unable “to connect Oswald with that address” despite the stamp on the back of FPCC pamphlets. As for Banister (who died of a heart attack seven months after the assassination), the FBI never placed him at 544 Camp. The FBI obscured Banister’s location from the Warren Commission by listing his office at 531 Lafayette Street-the side entrance to the building at 544 Camp.

Banister’s secretary, Delphine Roberts, said she interviewed Oswald during the summer of 1963 for the position of “undercover agent.” Oswald, Roberts said, was given an office for his FPCC work directly above Banister’s. When Roberts saw Oswald passing out pro-Castro literature on the street, Banister assured her “not to worry about him. He’s a nervous fellow; he’s confused. He’s with us.”

A frequent visitor to the building was David W. Feme, who used an office to the rear of Banister’s, Roberts said. Ferrie was a part-time “investigator” for one of Marcello’s attorneys. Two years earher, Ferrie had piloted the plane that flew Marcello back from Guatemala after his deportation. He also had ties to the CIA: he had trained pilots for the Bay of Pigs invasion launched from Guatemala.

Roberts says that Ferrie had worked under Banister as “a detective agent”: “I don’t know exactly what work he actually did. I don’t know whether he was running guns or whether he worked for Banister.” She says that Ferrie talked with Oswald at the offices “as if he knew him-I won’t say intimately.” She also recalls Ferrie and Oswald going to rifle practice together at an anti-Castro training camp.

On the day of the assassination, Ferrie was with Marcello in a New Orleans courtroom at a hearing on the deportation case. After the hearing, he and two others left by car and drove to East Texas to “ice-skate and hunt geese.” After driving all night, they pulled into a Houston ice-skating rink, where Ferrie waited for almost two hours at a pay telephone. The phone rang, Ferrie answered it and after a brief conversation, the trio left.

Three days after the assassination, Ferrie surrendered himself for questioning of the shooting in Dallas. New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison released him shortly after the FBI discredited a witness who accused Fer-rie of teaching Oswald how to fire a rifle. Garrison publicly implicated Ferrie as a chief suspect in 1967. Within days, Ferrie died.

Another secretary in Banister’s office, Mary Brengel, remembers seeing rifles propped up against the wall of Banister’s office and “how they talked over different qualities [of the weapons] in hushed tones over long hours.” As of the day of the assassination, those guns were gone.

Oswald was never grilled about his ties with Cuban exiles or organized crime. He lived only two days after the assassination, all the while claiming he was a “patsy” in the affair. Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby, who silenced Oswald with one shot, was judged by the Warren Commission to be another loner, spurred to kill by patriotism and sorrow.

The House Assassinations Committee discovered that Ruby Had mob ties dating back to the Thirties, in Chicago where he grew up. The panel also stated that Ruby made as many as three mob-related trips to Cuba just after Castro took control. It is thought that Ruby might have met with Trafficante in a Cuban jail. Ruby was known to have been a good friend of Joe Civello, reputed Mafia chief in Dallas in 1963. During the two months before the assassination, he made a series of long-distance telephone calls to acquaintances of Hoffa and Marcello.

Questions of Evidence

While the questions of crime and intelligence links are still troubling many assassination researchers, the issue of who fired how many shots in Dealey Plaza is just as vexing. Many people believe that Oswald didn’t fire a shot. Author Henry Hurt (who is in the process of writing a book on conspiracy theories) found “almost no evidence that Oswald had any capacity for violence. You have the FBI arguing that he did.” Oswald’s closest associate in Dallas, George de Mohrenschildt, thought that one reason Oswald was innocent of the assassination was that he “actually admired President Kennedy in his own reserved way.” Oswald’s wife, Marina, repeatedly referred to her husband’s admiration of Kennedy in testimony before the Warren Commission and the House Assassinations Committee.

Potentially explosive evidence of an assassination conspiracy not necessarily involving Oswald was discovered in 1978, when an amateur photographer re-examined some movie film he shot as the presidential motorcade moved into Dealey Plaza. Studying his film in slow motion, Charles L. Bronson realized for the first time that he had 92 frames showing the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository in which Oswald supposedly was perched at that moment. The eight seconds of window footage were shot about six minutes before Kennedy was slain.

Branson’s film was given an examination by Robert J. Groden, a photo consultant to the House Assassinations Committee. In a memo to the committee, Groden said that “close inspection and optical enhancement reveals definite movement in at least two and probably three of the windows in question.”

Branson’s film was first viewed by the FBI within days of the assassination, but it was returned to Bronson when an agent said that it “failed to show the building from which the shots were fired.” When the House Assassinations Committee learned of the film (about two months before its term expired), the panel had spent almost all of its allotted $5 million. Unable to afford a proper computer analysis to determine whether the figures moving in the windows were people, the committee recommended further scientific examination by the U.S. Department of Justice. An FBI agent who spoke with Branson’s attorney in late 1979 was unable to negotiate a temporary release of the film and hasn’t been back since.

Many unsettling aspects of Kennedy’s deathstill hang in the air: Do police Dictabelt recordings indicate that a fourth shot was fired fromthe grassy knoll? Is there significance in thefact that a known French terrorist was in Dallason the day of the assassination? Perhaps themost disturbing question of all remains: Willthe damning and intricate facts of Oswald’s lifeever be enough to indict a conspirator beyonda shadow of a doubt?

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.