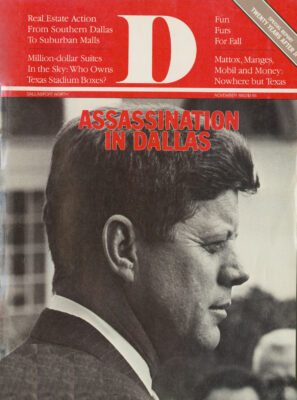

Hugh Aynesworth is the only reporter to witness not only the Kennedy assassination, but also Oswald’s capture and murder. Aynesworth covered all aspects of the Kennedy assassination for The Dallas Morning News and Newsweek and has written about the subject for newspapers from all over the world. He also has been a consultant to the three major TV networks and has appeared on more than 75 talk shows and documentaries about the case. He now lives in Dallas and is a free-lance investigative reporter.

November 22, 1963; Fort Worth, Texas.

John F. Kennedy awakens in suite 850 of the Texas Hotel, summons aide Kenny O’Donnell and asks him to order break-fast while he showers and shaves. Two eggs, boiled exactly five minutes, orange juice, toast, marmalade and a large pot of coffee.

Jackie Kennedy is still asleep in an adjoining room when O’Donnell makes a quick newspaper run, bringing back papers from Houston, San Antonio, Dallas and Fort Worth. The president is clearly pleased at the papers’ coverage of the previous day’s stops in Houston and San Antonio. Warm, responsive crowds had buoyed the spirits of the entire Kennedy party, particularly Jack and Jackie, who had been anticipating this foray into Texas.

Then Kennedy sees a full-page ad in The Dallas Morning News. It has a black mourning border and the headline “Welcome Mr. Kennedy to Dallas”; it’s signed by The American Fact-Finding Committee. The ad poses 12 questions to the president, each tinged with an archconservative slant.

Jackie hears the waiter bring in breakfast and walks, yawning, into the president’s room. Jack folds the paper with the troublesome ad on top and tosses it to her. “We’re really in nut country now!” He shakes his head. “How can people write such things?”

Kennedy hasn’t even seen the leaflets that were distributed around town the previous few days-fliers similar to FBI “Wanted” posters, complete with frontal and side photos of Kennedy with the caption “Wanted For Treason” written at the top. The newspaper ad pales in comparison to the leaflets: They accuse the president of betraying the Constitution, turning the government over to the Communists and lying to the American people.

Kennedy’s day will begin shortly with a speech in the large parking area adjacent to the hotel. From there, he’ll move on to a Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce breakfast and then to Dallas, where he’ll ride in a lengthy motorcade through downtown, up Sternmons Freeway to the Trade Mart for a luncheon. Here he’ll deliver a major address-a speech designed to mollify critics of the New Frontier policies and help heal the political rifts between the right and left in Texas, which is a “must” if Kennedy expects to be re-elected in 1964.

It’s raining, softly but steadily, and has been for much of the morning. In Dallas, the weather has cleared somewhat. But there’s at least a chance that the motorcade will have to proceed in the rain.

Secret Service Agent Roy Kellerman tells Kennedy and O’Donnell that agents in Dallas want to know if they should install the bubble-top on the president’s limousine. Both Kennedy and his aide snap, “No.” The entourage steps out into the hall, en route to the burgeoning crowd downstairs.

November 22, 1963; Irving. Texas.

Lee Harvey Oswald, a lean, rather uncommunicative man, rises early at a small bungalow at 2515 Fifth Street. He fixes himself a cup of instant coffee and dresses hurriedly before slipping into the garage, where he pulls a cheap Italian rifle from the folds of an old blanket, then conceals it in plain wrapping paper.

Back in the bedroom, he quietly pulls off his wedding ring and places it in a Russian cup. He stuffs $170 into a black wallet that his wife keeps in a drawer.

Oswald lets himself out of the tiny house and trudges half a block to Wesley Frazier’s house to hop a ride to Dallas.

November 22. 1963; Dallas, Texas.

I’m sitting in the Dallas Morning News cafeteria, sipping coffee and talking about the presidential visit. Bob Gooding, a Channel 8 anchorman, and James Hood of the News are with me. We talk about how everybody else seems to be madly involved in the preparations and how he and I don’t have much to do but relax and watch.

I tell Gooding that I hope there won’t be any embarrassment. I had spent the previous day trying to find out who had circulated the “Wanted for Treason” leaflets. I mention an ugly scene that had occurred a month earlier in which U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson was harassed. I’m afraid that current feelings in Dallas have escalated to a pitch at which radicals may try to prove a point before the national media.

Several reporters and photographers stop by our table. It’s about 11:30a.m., an hour before Kennedy will drive through downtown. I’m beginning to feel left out. For the previous three years, I had been fortunate enough to have one of the hottest beats on the newspaper: science, aviation and aerospace. I had covered several U.S. manned space flights; I had been to Cuba, Europe, Mexico and elsewhere; I’d flown many of the current military and commercial aircraft and had tested weaponry. At this point, the Morning News is one of only a few U.S. newspapers that covers such activities. But today, I feel left out. The more I talk with the other reporters, the more I wish I had been given an assignment downtown. It’s hard to stay out of the action. I’m reminded that I have a 2 p.m. interview with a scientist at SMU. I have to think hard to even recall the man’s name.

Shortly after 11:30,I spot a familiar face at the cashier’s station, a chubby little man dressed in black with an atrocious red-and-white tie. He’s carrying an overcoat over one arm and is carrying a tray with eggs, toast and coffee. An advertising salesman nearby shouts “Good morning” to him.

I turn to Gooding and say, “There’s that smart-ass, Jack Ruby. I guess he’s up here trying to get Tony Zoppi to put his name in the paper again.”

I can’t think of five people I have ever disliked intensely, but Jack Ruby is one. I have seen him beat up drunks in his clubs; I’ve seen him try to impress young, naive women with a roll of $1 bills, covered by one $100 bill. I’ve even reported him to the police for cutting a wino’s head open on Commerce Street, just across from the Adolphus Hotel. The wino had tried to bum a quarter.

Ruby has come to the News to see Zoppi, but the entertainment columnist has gone to New Orleans for a few days.

I decide to watch the president drive by. I can still make it to SMU by 2 o’clock. I turn and look at Ruby one more time, who feigns reading the paper as he tries to gaze up the switchboard operator’s dress at the next table.

WITHIN HOURS of that moment, Kennedy, Oswald, Ruby and I became victims of fate. Although the three of them arc long since dead, I have been unable to extricate myself from their presence in Dallas that day. Within the hour, I saw Kennedy shot. I was in the Texas Theater when Oswald was captured, and, two days later, I saw him gunned down by Ruby.

Although I wasn’t on the scene when Ruby died 38 months later, I did ride to the funeral home with his family.

That’s a strange sequence of events for a reporter who wasn’t supposed to be there…

THERE WAS an air of anticipation in Dallas that day. I don’t recall anyone expressing any serious concerns about Kennedy’s safety, but some expected embarrassment from the lunatic fringe, which seemed to have found a home here.

The previous day, I had received a call from a Grand Prairie group that protested being questioned by Dallas police after publicly stating that it planned to picket the president’s entourage at the Trade Mart. The Dallas police had visited several well-known far-right groups during the days before the presidential visit. They were told that freedom of speech was one thing, but that any embarrassing display similar to the one that Adlai Stevenson had endured in late October would be met with firm force. The message was clear: Better stay home and watch the procession on TV.

The members of the Grand Prairie group (six or eight die-hards) insisted that they would show up anyway, that they had a right to protest. Emotions were running so high that I thought the group might stir up something. I suggested to City Editor John King that I write a story about their plans, explaining what they wanted to prove. King snapped, “Hell, no. To do that would bring out another SO crazies. Let’s just ignore ’em.”

When I dropped by the photo department to see who would be going to SMU with me to shoot a picture of the person I was to interview, I saw staff photographers Jack Beers and Joe Laird heading out to photograph the crowd. I decided to walk up to the police station to visit longtime police reporter Jim Ewell. I wanted to know whether the police were onto anything else with the extremist groups. I had this funny feeling…

Ewell wasn’t in the police press room, so I wandered back down the streets. The crowd was growing. Many people were carrying transistor radios, listening to coverage of Kennedy’s arrival. The throngs along Main Street were already two- and three-deep.

Kennedy’s motorcade wasn’t due to arrive for a few minutes. As I headed west, I stopped several times to speak with people I recognized. I guess it isn’t every day that you get to see the president, but the crowd’s excitement seemed more intense than I had expected. There were more buildings along the route back then, and in almost every window, two or three people watched the scene below.

As I approached Houston Street, I saw several fellow News employees and some county employees I knew. The Kennedy entourage had left Love Field, the radios blared. I decided to swing around Houston Street and head for the intersection at Elm. The motorcade would have to make a rigid left turn there, and I knew the cars and buses would have to slow down. I wanted to get a close look at the Connallys and Kennedys and my buddies on the press bus.

There seemed to be plenty of police around, barking orders to each other. Near the intersection of Houston and Elm, I chatted with an assistant district attorney I had known for several years. He was always interested in hearing about the manned space program and the astronauts; I told him how chaotic the covering of the launches at Cape Canaveral had been. I didn’t really know what chaotic meant yet.

I could hear the clapping and cheering on Main Street before the motorcade turned onto Houston. It was 12:29. Here they came- gliding along, maybe 10 to 12 mph. Two teen-agers jumped in front of me, jostling each other in their excitement. I moved a few feet closer to the intersection to get a better view.

To my left stood a large woman holding a small child in her arms. A woman standing beside her squealed, “Hey, look! She’s got your dress on,” referring to the pink suit that Jackie Kennedy was wearing. It was the same color, but it was at least 10 sizes smaller.

As the presidential car drove by, Gov. Con-nally and his wife, Nellie, radiated pride. They too had been anxious about Kennedy’s visit, but it appeared that, so far, everything was going beautifully. Both Connally and Kennedy seemed to notice the huge woman waving frantically with one arm, the small child dangling from the other. (Nellie Connally later testified that she had just said, “Well, Mr. President, you can’t say there aren’t some people in Dallas who love you!”)

The rest of the motorcade passed by. I could see Sen. Ralph Yarborough sitting to the left of Vice President Johnson and Lady Bird. He had a frozen smile on his face, but he didn’t really look like he was having much fun.

Then it hit.

A pop, like the backfire of a police motor-cycle. A nearby cop was tensed. A few seconds later, there was a second pop, then a third. Gunfire! “Hey! Hey!” a big man in a cowboy hat shouted, as though he could stop whatever was happening by being assertive. Two or three cops stopped short, then ran in different directions. A motorcycle policeman veered to his right. People started yelling and running. The woman in the pink dress turned, clutched her stomach and threw up on the street. A man holding a small boy threw him down on the sidewalk, shielding the child with his body. Some people clung to each other. Some ran. It happened so fast. People pointed at the Texas School Book Depository building and the Tex-Mart building across Houston Street. I couldn’t see much of the president’s car. It had dipped down and was headed southwest on Elm Street. The rest of the caravan sped up a bit. People were crying and screaming.

“The president’s been hit,” one man cried. “Oh my God, the president’s been hit.” “I think Lyndon Johnson was hit, too,” another said.

It’s hard to recall the next few minutes. I remember running over to the front of the Depository building and listening to people there tell how they had seen the president shot. I looked at the triple overpass and saw three or four people running along the tracks. That’s where the shots must have come from, I thought. About that time, several policemen ran into the Depository building. I tried to follow but was stopped by a menacing cop with hands like hams. As he blocked me, a WFAA newsman ran inside.

Somebody said that a Secret Service man had been hit off to the west side of the building. Five or six of us ran in that direction. We didn’t find a thing.

I didn’t have a notebook with me, but I had some envelopes and started making notes on them. Jim Underwood, a KRLD newsman, was interviewing a man who kept pointing up to the top of the Depository building. I quickly nosed in. The guy said his name was Howard Brennan and that he had seen the assassin.

Brennan said that he had seen the man before the motorcade arrived. Brennan had scoured the windows of the TSBD from directly across the street. At that time, he said, he hadn’t seen a gun. Later, when he heard what he thought was a firecracker exploding, he looked back up to the sixth-floor window and saw the man aim, fire, then hesitate a few seconds-as if to see whether his shot had hit its mark.

A cop asked Brennan a few questions, then took him away to a car parked near the Depository building. Brennan described the assailant as being about 5-foot-10, in his late 20s or early 30s, thin with a khaki-colored shirt, about 160 to 165 pounds. (Later, I found out that Brennan’s description was the first to go out over the police radio. I also learned that during the procession of Kennedy’s motorcade, News employee Sally Holt had focused her camera at the back of the limousine, directly toward the TSBD at just about the time the car slowed to make the turn onto Elm. After it was determined that the shots had originated from the TSBD, she ran back to the News, where in her haste to unload the film, she exposed the roll. This might have been the only photograph taken that would have shown the assassin in the window; no other such photograph has ever surfaced.)

I interviewed at least 10-maybe 12-people until my envelopes were covered with notes. Oddly enough, all but Brennan said that there were definitely three shots. Brennan, the sole eyewitness, recalled only two.

A few minutes later, I strayed back to the front of the TSBD building, where I saw several Times Herald reporters huddled in a tight circle. I don’t recall all of them, but John Schoellkopf and Paul Rosenfield were there. I tried to inch in to see what they knew. Schoellkopf pushed me aside and told me to go away. They were planning their coverage and didn’t want the competition listening in. I got angry at Schoellkopf and was about to push him back. Rosenfield calmed the situation. I left. I saw four women from the News’ women’s department (as it was called then) and talked to them briefly. They agreed that the shots had come from their left-the direction of the TSBD. Later, one of them would incorrectly state that she had heard shots from over her right shoulder-a remark she quickly corrected. (Conspiracy theorist Mark Lane used that misstatement to “prove” his “grassy knoll” theory years after she explained to him that she had erred in the chaos of the moment.

Jim Ewell, a News reporter, had arrived at the TSBD; we talked about what we should do from there. Rumors were circulating that the president was dead and that LBJ had been badly injured.

One woman swore to me that she had seen Johnson slump over in the car. Later, we learned that Secret Service Agent Rufus Youngblood had tossed the vice president onto the floorboard and had covered him with his body. LBJ suffered a sore shoulder, but no serious injury.

Vic Robertson and another WFAA-TV newsman arrived shortly, and we all milled around-talking, interviewing, sticking close to radios. We wanted to watch the search in the TSBD and hear what was going on at Parkland Hospital at the same time. Soon the radio on a parked police cycle blared that a police officer had been shot in Oak Cliff. Then a policeman told Ewell that they thought they had the gunman trapped on the top floor or the roof of the TSBD.

The call about the shooting in Oak Cliff spelled conspiracy to me. It has to be connected, I told Robertson and Ewell. I suggested that Ewell stay at the TSBD (he knew the cops well after 10 years of police reporting; they weren’t likely to tell me anything) and I would high-tail it to Oak Cliff where the policeman had been shot. Robertson and the other Channel 8 reporter said they had a WFAA news unit. We all left together.

Robertson and I hung out the windows, waving and shouting as the driver of the WFAA unit raced toward the scene of the officer’s killing. We ran red lights and hit 90 mph; a couple of times we almost crashed at intersections. Five minutes later, we were on 10th Street, watching a distraught woman named Helen Markham describe how Officer J.D. Tippit had been gunned down. The ambulance had just removed Tippit’s body. Several police cars, FBI agents and newsmen began to arrive. Two girls said they had seen the assailant run from the scene. A man said the gunman ran into an old house on Jefferson. Several of us ran to the house. It was a furniture storage facility; some rooms were stacked high with old furniture. Bill Alexander, an assistant district attorney, ran into the house with some cops. I ran after them. We could hear somebody running upstairs.

Nobody stopped me, so I inched my way into the old, cluttered house. A few seconds later, whoever was running upstairs gave an agonized shout as the floor gave way and he fell partially through the ceiling. I gave a terrified scream myself; I was standing right below. About that time, I realized that everybody in that building had a gun except me. I hurried outside to watch from a more sensible vantage point.

It soon became apparent that no one other than police were inside the house, so we drifted back out into the street. We heard a report on the police band that someone had sighted the gunman in the public library. Moments later, word came that it was a false alarm.

Meanwhile, police had scoured the TSBD and had found the assassin’s rifle but no suspect. Many police were reassigned to search for Tippit’s killer.

I have no idea who was with me at that point. As I moved westward on Jefferson, a man ran out of a used car lot and shouted, “I saw him. I saw him. He went that way. I tried to stop him, but he moved too fast for me.” He pointed to an alley. Police stopped to get more information as I moved on.

A block or so up Jefferson, I saw an old woman, probably 75 or 80, sitting on a curb and sobbing quietly. She looked up at me, alarmed. “Do you live near here?” I ventured. “Do you know where I could use a telephone?”

Before she could answer, two police cars sped around the corner with an obvious destination in mind: the Texas Theater, which I could see up ahead. Eight or 10 people were milling around in front. Another dozen or so had arrived before I could get there.

“They’re both inside,” shouted a wiry man, pointing to the theater. “Both of ’em. I saw ’em as I was drivin’ by.”

A woman in her early 30s talked to several policemen. “He’s inside. I don’t think he bought a ticket. I don’t remember what he looked like.” The woman, later identified as Julia Postal, sold tickets at the Texas Theater. She said she had sold 23 tickets, but later we found no more than 15 or 16 persons inside.

As I ran inside the theater, my immediate thought was to run up to the balcony to get a better view of what was happening. But, frankly, I was afraid. The scare at the old furniture storage house had gotten my Adrenalin pumping, but it also had caused me to exercise some caution-if you can imagine a reporter chasing an assassin being cautious.

I decided not to go upstairs. I figured that if I were running from police, I would probably head for the balcony. I was also afraid to barge into the downstairs area.

I didn’t know who was in there or if he was armed, but I was so wired that I had to see. I slinked rather cowardly over to the right aisle doors and peered in. Two cops almost ran over me. I plastered myself up against the wall.

The house lights had been turned up-not all the way, but they were considerably brighter than usual. The movie was still running. Four or five men were walking matter- of-fectly up the aisle-two directly in front of me and two in the left aisle. There seemed to be additional movement as though another person or two were converging from the left. (Later, I found out that two men sitting close to the front had been shaken down.) Then, a man walking toward me (later identified as Officer N.M. McDonald) suddenly stopped, turned toward a man sitting five seats off the aisle and said “Get up” or “Get out.”

McDonald moved quickly for a large man. So did the smaller guy, who jumped up and said something I couldn’t hear and then threw his hands up in the air. Officer McDonald reached toward his waist to check, I assumed, for a gun. Seconds later, the suspect threw the officer a glancing blow with his left hand, then a solid hit with his right.

On August 2, 1982, then-Land Commissioner Bob Armstrong wrote Attorney General White suggesting that White sue. On December 31, 1982, after negotiations had broken down, White finally did. Mattox inherited the suit.

Seafirst Bank, meanwhile, had watched some of its energy loans go sour and tried to foreclose on Manges. He says his deal with Seafirst was that he would pay only the interest on his notes, leaving the principal to be paid after the Mobil suit was settled. But in the process, the facts of the $125,000 loan to Mattox’s brother and sister and the subsequent loan of $125,000 by Mattox to his campaign were leaked to The Dallas Morning News. The News reported that when Mattox’s campaign repaid him for his loan, his siblings, Janice L. and Jerry S. Mattox, repaid Seafirst the next day- the exact amount of $133,797.57 (the loan plus interest) that Mattox had repaid himself.

Mattox reportedly grew incensed that Mobil attorney Tom McDade of the powerful Ful-bright & Jaworski firm of Houston wanted to depose Mattox’s sister about the loan. He allegedly threatened J. Wiley Caldwell, also of

suspect was screaming, “I protest this police brutality,” as they shoved him through the front door toward a waiting police car. One man preceded him into the back. Four others got in the car as it sped away.

At least 200 people had arrived by then, and many were chanting, “Kill the son of a bitch!” “Let us have him.. .We’ll kill him!” One cop wiped tears from his face and ran around the corner toward the back of the theater. I felt like crying myself.

I called the city desk and told an editor that I had seen the capture and that a suspect was en route to the jail. Somehow, they already knew. I was told to interview whoever was left and then get back to the office. I don’t remember how I got there-probably with another newsman-but I returned about 2:30 to begin typing my notes. The suspect, we were told, was a one-time Russian defector, Lee Harvey Oswald.

The newspaper was a madhouse. Some people reacted to the day’s stress with dignity and professionalism; some didn’t. Some openly wept as they exchanged views or talked to loved ones on the phones. Several members of the visiting press had returned from Parkland Hospital and were typing frantically. The News’ reference department was already a shambles, with out-of-towners scooping up files on all the leading participants.

City Editor Johnny King personified grace under pressure. An old pro, King had become somewhat disenchanted with the routine of his job. But now he was superb, barking orders, sending his troops into battle, running back and forth to assist Managing Editor Jack Krueger and his assistants, Bill Russ and Tom Simmons, in planning the day’s presentation.

By midafternoon, we had learned that police and FBI agents had confiscated the suspect’s belongings from two different places: a house in Irving and a rooming house in Oak Cliff. We got the addresses. Someone sped off to Irving; I headed for the Oak Cliff address. Trouble was, Oswald’s wallet had held two street numbers in Oak Cliff. I picked one on Neely Street. I was amazed that no police or other reporters were there. I could hear people talking inside. God, I thought, could I be lucky enough to find some people who knew the man?

I knocked. A radio was quickly shut off. I knocked again. No one opened the door. I kept rapping. Finally, a huge, scowling man clad in nothing but shorts two sizes too small opened the door. He spoke Spanish. Behind him, I saw a busty, nude woman on a rollaway couch struggling to cover herself.

“Do you know Lee Harvey Oswald?” I asked several times, backing up a step or two as the man continued to glare at me.

I had seen enough violence that day so I turned and said, “Sorry,” and got out of there.

The second address, on Beckley, was more fruitful. I encountered an elderly woman, Earlene Roberts, who said, “They’ve just left. I told them everything.” She obviously thought I was a cop. “I just want to make sure I know everything,” I said.

“You wanna see his room?” she asked, as she stepped back inside. “It’s right there-not much to it.” Right off the living room was an 8-by-ll-foot room, with crummy curtains, a bed and a small dresser. A banana peel lay in an otherwise empty wastebasket.

She told me that the man had registered under the name “O.H. Lee” and that he had only been there for a few days. Mrs. Roberts said she had been watching TV coverage of the president’s assassination when her tenant had come running in. She said that he wasn’t too friendly and that he had run back out a few moments later without answering her. “He was a weird one, a real weird one,” she said.

She tried to tear out the page to give me the receipt on which he had signed “O.H. Lee.” I figured that police would eventually want that handwriting, so I declined, thanked her and left.

I headed back to the office, where I wrote a few more inserts for the main story, then called home. My wife, Paula, was about three months pregnant, and I wanted to assure her that I was safe.

I finally left the newsroom at about 10:30.

Although I had lucked into some incredible leads that day, I wasn’t assigned a story to work on over the weekend. The News had fine, established police reporters, court reporters and general-assignment reporters to handle every aspect of the story now.

Again, I felt left out. On Saturday, I stationed myself in front of the TV and watched the nation launch its “Hate Dallas” stance. I had an odd premonition about the plans to move Oswald from the Dallas City Jail to the Dallas County Jail.

I called Johnny King and volunteered my services. “You’re the science editor,” he said cajolingly, adding, “but if I need you, I’ll call you.”

November 24, 1963; Dallas, Texas.

I awoke very early. TV commentators announced that the move still hadn’t been made. Oswald would be moved at 10 a.m. Live coverage was promised.

“I’m going down to the police station to watch,” I told my wife. “Not unless I go with you,” she said.

We sped downtown, parked a block away from the City Building and ran toward it on the Commerce Street side. I tried to enter the basement near an armored car parked half-in and half-out of the building. Paula was stopped. My press credentials were checked three times, but finally I eased down the ramp. Some 75 people were jammed in a semicircle around the doors that led to the police department.

I hadn’t been there two minutes before I heard somebody shout, “Here they come!” The strobe lights went off, and a couple of dozen reporters inched toward the doors. Capt. Will Fritz and two of his homicide detectives walked out with a handcuffed Oswald. Two seconds after they were outside the doors, a blur leapt in front of the group. A shot rang out. “Oh my God,” I thought, “not again]”

Several cops immediately jumped on the man holding the gun and wrestled him down. It seemed as if there were so many wrestling that there was no room for the gunman on the ground. He held his arm high-the gun still in it-as the mass struggled to get him under control . It was a full five minutes before I found out that Ruby was the killer.

Some officers pulled Oswald to a nearby holding area. An ambulance arrived. It must have been very close by. Thrown onto a stretcher, Oswald was hoisted into the ambulance, as reporters stared at each other in disbelief. Then almost as one, they bolted to telephones. I tried to get inside to see where the gunman had been taken, but the door had been shut off by cops.

A Kansas City reporter staying across the street at the Statler Hilton Hotel offered me a phone-after he finished. I told him that I needed to check on my wife, who was somewhere outside.

I found Paula out in front, and we drove home to drop her off. I had to get back to the News to report what had happened. I was excited about seeing the picture that News photographer Jack Beers had taken. Beers, an old pro, had been standing to Oswald’s left as he was escorted through the basement doors. I knew that Beers must have taken a great picture at just about the time the gunman shot. (As it turned out, Beers’ photo ran a full front page the next morning. The News thought it would be a sure-fire Pulitzer Prize winner, until Bob Jackson developed his film over at the Times Herald. Jackson’s photo showed Oswald being hit by the bullet; Beers’ photo was taken about a second before that. Jackson won the Pulitzer.)

WITHIN HOURS, Eva Grant, Jack Ruby’s sister, had hired Tom Howard as Ruby’s lawyer. She came down to visit Ruby in jail and went across the street to Howard’s law office. She talked briefly with me and a couple of other reporters, but she offered nothing substantive.

Accompanying Mrs. Grant was Tony Zoppi, the News’ entertainment writer, who was as close as any newsman to being a friend of Ruby’s. Zoppi, now the public relations director at the Dallas Fairmont, was of no help. I followed them into Howard’s office, anyway.

Howard, Zoppi and Grant were soon ensconced in a front office, making phone calls. They called Ruby’s brothers and sisters in St. Louis, Chicago and Detroit; they tried to get in touch with superlawyers Percy Foreman in Houston and Jack Erlich in Los Angeles. I slipped into a back office and gingerly lifted up the phone to eavesdrop as they dialed each call. As they searched for Foreman, I began sneezing and had to hang up. I never learned the contents of that conversation.

It was almost midnight when I finally got home. If Friday’s events at the News had been traumatic, the scene on Sunday night was even more bizarre. The unthinkable had happened .. .and then happened again.

I still wasn’t ready to go back to science writing on Monday morning. My best buddy, News columnist Larry Grove, and I decided over coffee that since no one knew how Oswald had gotten from the sixth floor of the TSBD to the Texas Theater in Oak Cliff, somebody needed to dig up information on that. King was kind enough to let Grove and me loose to work together on that story. Five days later, before the Warren Commission was even named, we had an exclusive story on Oswald’s comings and goings, the time sequence of events and a list of the people Oswald had encountered along the way.

I guess I forced myself into the fore. No longer was I shut out of the big story. I later covered the Ruby murder trial, wrote exclusively about Oswald’s Russian diary, was the first print journalist to interview Marina Oswald and was the only reporter inside at Ruby’s funeral.

For years I was called upon to respond to the myriad conspiracy theorists who dropped their offerings on an uninformed (or misinformed) public. When New Orleans Dist. Atty. Jim Garrison revved up his Clay Shaw conspiracy case, I spent nearly two years covering every aspect of it for Newsweek.

The entire experience entailed a lot of work,intrigue and pressure. For a newsman-and fora lot of citizens-the weekend of November 22through 24, 1963, was unforgettable. Believeme, at times I’ve tried.