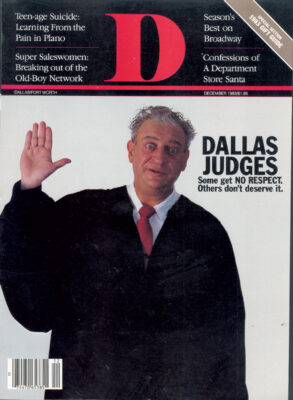

SOME PUBLIC OFFICIALS play their power to a fully lit house, inviting scrutiny from all around. Every president has his James Watt; every mayor, his Elsie Faye. To them, a scathing media blitz is the nature of the game.

But not judges. Even humble jurists-if there are such animals-wield their power from on high. The simple donning of a black robe has the effect of transcending the code of mortals. We’re not quarreling with that. These days, authority figures need all the authority they can muster.

But once in a while, somebody needs to peek behind the bench. There will always be judges who don’t do justice to the job. Judges are human. Worse, they’re elected. The majority of voters wouldn’t know an Annette Stewart from an Annette Strauss. We’d go so far as to bet a back cover that eight out of 10 registered voters in Dallas County can’t name a single judge.

The power vested in these mystery men and women is awesome. The responsibility they carry is even more so. In the course of a day, a judge makes more profound decisions than most of us make in our lives. A single rap of the gavel can send a felon to prison for life. A swipe of the pen can return a dangerous criminal to the streets. A yea or nay can award a plaintiff millions of dollars or deny him a cent.

Applauding a judge with that elusive mixture of intellect and integrity is a welcome task. Bearing the bad news of an idol who has fallen is not. We have been raised to regard judges as somehow deified, rare, above reproach. In most of our minds, judges rank somewhere between the elementary school principal and God.

But the cold, dispassionate facts are these: By and large, Dallas County has a stable, strong judiciary. The last election (November 1982) ushered in several bright new stars, preserved some seasoned pros and, in at least one case, restored to the bench a veteran who had previously gone down in defeat. A few bad apples were left on the tree.

It’s mind-boggling how little we’ve known (for how long) about these ministers of fate. On that score, we owe a debt to the Committee for a Qualified Judiciary (CQJ). The CQJ, a hand-picked, diverse group of citizens-lawyers and otherwise-was formed to do our pre-election homework when judicial ballots are cast. On a volunteer basis, these men and women wade through stacks of exhaustive questionnaires and conduct lengthy personal interviews, then otter their picks in each contested race. The last election was the first the CQJ worked, and there’s no way to gauge how many voters took its slate to the polls. But 18 out of 20 endorsed candidates won.

The Republican sweep of 1980 (when President Reagan and Gov. Clements rode a ballotful of candidates on their coattails) got rid of some judicial deadwood, but it also shooed out some fine judges. The election had the effect of hammering home a point that many people already knew: The two-party judicial election system stinks. First, it requires would-be judges to wage a real political battle, and that requires cash. Who, besides a few close friends, is going to contribute to a judge’s campaign? Lawyers. And what judge, looking at two lawyers in front of him, one of whom contributed money and the other of whom didn’t, is going to rule impartially? Politicking has other costs as well: namely, time and privacy. Stepping into the ring in your sweats is not always appealing to the type of person who aspires to be a judge.

That’s not to say that judges should be immune to scrutiny. Accountability is essential and must be preserved. Some options under consideration include ballots without party labels and appointments with the right of recall. Neither is a perfect system, but more is at stake than simply the ferreting out of the bad judges from the good. The method must also encourage well-qualified, worthy candidates to run. Well-qualified, worthy judges are not yet on the endangered species list. But as you will see, we have, along with the good, our fair share of the bad and the in-between.

A valued spinoff of studying Dallas’ 70 plus-member judiciary was that we walked away with a sharper insight into what makes a good judge. We discovered that knowledge of the law must be countered with a gut instinct for doing what is right. Good judges don’t inject themselves unnecessarily into the process of a trial. But neither do they fear going out on a limb: A strong jurist makes rulings and is not afraid to make law. The more highly-rated judges operate free from interference or overt bias toward either the prosecution or the defense. They temper punitiveness with mercy.

How did we rate the judges? We drew our conclusions from several sources. First, we looked at data that is part of the public record: court costs, collected fines, total case dispositions, grievances filed. Then we studied the Dallas Bar Association’s judicial evaluation polls, the most recent of which was issued in November. Some lawyers attack the bar poll as being a popularity contest. The theory is that even though opinions are offered anonymously, attorneys hate to berate the powers by which their clients stand or fall. Some judges who are known to be fully competent but who are consistently rude to lawyers get bad marks. Still, almost 1,000 attorneys respond to the bar polls when they appear every off-election year. They’re useful for pointing out the judiciary’s best and worst.

Our third and most productive means of gathering information was private interviews with some 35 lawyers. Offering their insights confidentially, our panel of attorneys spoke with candor about legal acumen, judicial temperament, bias, creativity and courtroom style. It was reassuring to watch profiles develop as one attorney after another echoed the characterizations of his peers. Unintentional but inherent prejudices on the lawyers’ part were stacked up against the facts.

All in all, we emerged with a healthy respect for judges who do their jobs well and with an outrage at the longevity of several who don’t. No elected official has an influence that is more direct. Justice is not always swift or sure, but it is inevitable. By the same token, frightful are the dangers of abuse. So many factors can stand between a judge and justice: an overcrowded docket, a personal slant, fear of reversal, human error. The system is complex enough to require seasoning before mastery. In the immortal words of Federal Judge Jerry Buchmeyer, whose pen is as mighty as his gavel, “Doing Justice is like a love affair: if it’s easy, it’s sleazy.”

Best of the Young lurks

Sid Fitzwater

298th Civil District Court. Born: 1953. Baylor Law School. Admitted to bar: 1977. Appointed to bench: 1982.

A good judge, lawyers tell us, blends intelligence with insight; an understanding of the law with an understanding of the human plight. Seasoned judges bring to the bench the sum of their experiences; newer judges add a fresher slant on the law and the enthusiasm of youth. One distinguishing feature of the 1983 civil bench is its crop of the latter-a group that attorneys have nick-named “The Young Turks.”

The Young Turks-Sid Fitzwater, Nathan Hecht and Craig Enoch-have been judges for less than two and a half years. All three are under 35 years old. Besides dispelling the myth that judicial demeanor requires a crop of white hair, these young jurists have brought an invigorating breath of fresh air to the courtroom. Our panel of lawyers applauded their willingness to work hard, their exuberance for the job and their superior ability to grapple with complicated legal points.

The youngest of the lot-who recently reached 30-is Sid Fitzwater; a man who, despite his Wunderkind image, inspires comments from usually cynical lawyers such as, “He may become the best state court judge we have.” Fitzwater is said to be smart, careful and absolutely dedicated to being a judge. How can you fault a guy who says that his judicial aspirations date to his Little League days when he “always wanted to be umpire.” Fitzwater and the other young judges have not been content to sit back and watch the wheels of justice creak with age. They’ve made changes where changes were due-like Fitzwater’s assignment of specific times for attorneys to show up for hearings so the lawyers wouldn’t have to sit around all day.

But you can’t please all the people all the time, and there are those who fear that Fitzwater’s “intense Republicanism” will influence his rulings. Formerly an active party member and one of Gov. Clements’ appointees, Fitzwater seems eager to put politics aside. Ironically, he may be damned if he does and damned if he doesn’t; one civil defense lawyer complained, “He’s not as conservative as I’d hoped.”

Most Compassionate

R.T. Scales

195th Criminal District Court. Born: 1923. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar: 1951. Appointed to bench: 1969.

“Rootin-’Tootin’ ” Scales takes the prize for having the most staying power as well as for having the biggest heart on the Dallas bench. Scales underwent sextuple-bypass heart surgery in 1978. After the operation, he discovered that he could no longer read and he had trouble remembering things. But he didn’t give up.

since returning to the courtroom a little more than a year later, Scales has worked hard to relearn reading skills. He spends hours wading through cases at home every weekend. His progress has been slow, and the legal community has had every opportunity to call for his resignation. But that call hasn’t been heard. This judge’s record remains spotless and he routinely goes out of his way to keep from sending someone to prison. He hasn’t been hardened by the parade of rapists, robbers and murderers that passes before him, as so often happens to criminal district judges, but instead has maintained a fair outlook, according to attorneys from both sides. He is considered by many to be one of the most lenient judges on punishment, but he’s tough on parole violators.

“Scales is a really refreshing individual,” one attorney says. “If there were more like him, the judicial system would be all right.”

Least Compassionate

Gerry Meier

291st Criminal District Court. Born: 1949. Texas Tech Law School. Admitted to bar. 1975. Appointed to bench: 1981.

If you’re thinking of committing a felonious crime, pray you aren’t sentenced in Gerry Meier’s court. The first female criminal district judge-known around the criminal bar as the “Iron Maiden’-will probably sock you away.

Gerry Holden Meier, say fans and foes alike, is tough. Lawyers are divided on whether she is also fair, and it’s no coincidence that most of the criticism comes from the defense. Meier came to the bench straight out of Henry Wade’s office, where she rose to prominence as one of the best- and the only female-chief felony prosecutors that Dallas County has had. She was so convincing in front of a jury that defense lawyers still quake at the memory of facing her on the state’s side. Some say that if she hadn’t been appointed judge, she might have been the first female district attorney.

The jury is out on whether Meier will rise to the same level of competence as a judge that she achieved as a prosecutor. Some fear that she is “too cold a person” to ever fully comprehend the human condition. One verdict is in, though: Meier is tough on punishment. “I think she’s really fair on guilt or innocence, but when it comes to punishment, she’s hell on wheels,” one attorney says. Another adds, only half in jest, “Any lawyer who willingly submits his client to punishment in Gerry Meier’s court has probably laid the grounds for a malpractice suit.”

Most Controversial

Tom Price

County Criminal Court #5. Born: 1945. Baylor Law School. Admitted to bar: 1970. Elected to bench: 1974.

If you’re looking for the judge who leads the pack in notoriety, you’re looking for Tom Price. His span on the county criminal bench has been marked by one screaming headline after another. Most recently, Price drew fire (and, from some people, a measure of muffled praise) for acquitting Sheriff Don Byrd in his infamous run-in with a lamppost in University Park.

When Price came to the bench in 1974, he was 29 years old and the youngest judge ever to be elected in Dallas County. The fact that he was elected at such a young age and on a first run was itself noteworthy. More often than not, judges are appointed and later run for election.

Price caused a flap almost from day one. At times, he seems to revel in being in the hot seat. Even his staunch supporters admit that “he’s a bit of a self-promoter.” Somehow, cases that are accompanied by heavy news coverage-such as the Mexia drownings and the Byrd trial-happen to land in Tom Price’s court.

No issue has received more publicity than the longstanding feud between Price and District Attorney Henry Wade. Price claims that Wade has been out to get him ever since it became obvious that Price ran his court without kowtowing to the district attorney. Wade contends that some of Price’s courtroom practices are sloppy, at best-and at worst, outright illegal. A complaint from Wade detailing Price’s misconduct on a number of counts resulted in an official rep-rimand from the Texas Commission on Judicial Conduct.

Price has thrown fuel on the fire by admitting to the press that he regularly “borrows” weapons from the evidence room to arm himself on the bench. If that didn’t make the point, he added, “I want to be able to blow their heads off if I have to.”

Despite the furor that follows Price, he has his friends; friends who respect the fact that he is, in one’s words, “very much his own man.” Then there are those who insist that Price flirts with the unscrupulous, if not the corrupt. In the end, everybody picks sides on this judge. Says one attorney, “You’re either against him or you’re not.”

Most Pleasant Surprise

Mike Keasler

292nd Criminal District Court. University of Texas Law School. Admitted to ban 1967. Appointed to bench: 1981.

Loud groans echoed all the way from the Dallas County courthouse to the headquarters of the criminal bar when Mike Keasler took the bench in September 1981. “Mad Dog Mike” was one of the least popular prosecutors-in quite a large field-who had ever worked for the district attorney. His exploits as a state’s attorney were legendary. Defense opponents remember him as antagonistic and manipulative, with a dirty trick up each sleeve. One lawyer recalls, “Every time I tried a case against Keasler, I wore out a pair of shoes, I was on my feet so much.”

And then Mike Keasler became a judge. The same group that had bemoaned Keas-ler’s lead-pipe trial style now offers him nearly unanimous praise: “He has an innate sense of fairness and forgiveness.” “He is courteous to both sides.” “He’s doing his damnedest to be Mr. Good Guy.” And finally, from the one who professes to have moaned the longest and loudest of all: “Mike Keasler may just be one of those people who was meant to be a judge.”

Most Judicious

Thomas B. Thorpe

203rd Criminal District Court. Born: 1929. St. Mary’s University Law School. Admitted to bar: 1951. Appointed to bench: 1973.

Few disparaging words are heard about the man they call “Thoughtful Thorpe.” Adjectives we recorded again and again describe, as one lawyer says, “the archetype of a good judge.” Thorpe is, according to our panel, unbelievably hard-working, a superior legal scholar, even-tempered, principled and fair.

Much of Thorpe’s judicial wherewithal comes from within. He is a devout Catholic, and although he doesn’t “wave his beliefs around in the courtroom,” he often slips away to pray before assigning sentences. Says one counselor, “You may not agree with him, but you can’t fault him for absolute fidelity to principle and for trying to do right. He works hard; he struggles. He has ideas and notions of how things ought to be.”

For those reasons, trying a case in Thorpe’s courtroom is no piece of cake. If an attorney wants something special for his client, he’d better have the case law to show the judge. One panel member says, “He makes me a better lawyer.” The only problem is that Thorpe sometimes has a little trouble not being a lawyer. Often, there are three voices for the jury to listen to. Another complaint about this jurist so girded with superlatives is that he’s awfully tight with the state’s money. The legal minimum for appeals cases involving court-appointed indigent defense is $350; Thorpe pays not a penny more (most other courts pay at least $500). As a result, several fine attorneys refuse to practice anywhere near him.

But thrift is forgivable. More memorable Is that even after 10 years on the bench, Thorpe still agonizes over the right thing to do. Before the last judicial election, “when the rats were jumping the sinking ship of the Democratic Party” and becoming “Lady Clairol” Republicans (only their precinct chairman knows for sure), Thorpe remained steadfast, risking his retirement income in an election that could surely have been thrown by party lever-pullers.

All that’s left, then, is the usual question: “But can he dance?” Our panel says “yes.” As one fan puts it, “Thorpe’s a good judge and one hell of a dancer.”

Biggest Buffoon

Dee Brown

Walker

162nd Civil District Court. Born: 1912. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar: 1935. Appointed to bench: 1963.

Anybody who has spent time in Dee Brown Walker’s courtroom knows this routine: The judge takes the jury for a tour of his chambers after the trial. His bailiff happens by and says, “Say, judge, did you show them the book you wrote?” “No, by golly,” answers the judge. Then, turning to the jury, “Let me show you the book I wrote.” He hands a juror a copy of a book entitled Everything I Know About the Law by Dee Brown Walker. The pages are blank. Guffaw, guffaw.

Some people don’t think Walker’s antics are funny. In 1981, law librarian (now attorney) Sheila Porter filed an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint against the judge on the basis of sexual harassment. Another lawyer says that in a recent personal injury case, while he was attempting to obtain the medical records of a defendant, Walker asked him “if the guy was a nigger.” The attorney remembers Walker saying that if the man was, it’d be more important to get the records ” ’cause those guys have more VD than white folks.”

Walker regularly receives among the lowest ratings in the Dallas Bar Polls. His docket is stacked up like Central Expressway. Lawyers say that trying a case in his courtroom is “similar to being in quicksand.” He is known for getting bogged down in complicated disputes, for getting side-tracked and for whacking jury settlements in half.

In our last poll, D named Walker “Worst Judge,” and he may well deserve the title again. But for many attorneys, the relationship is love-hate. “The best thing about Walker is that he’s always there,” says one. Walker is known far and wide for issuing TROs (temporary restraining orders) at the drop of a pen. Fans say that he’s a caring man: “He tries to do what’s right regardless of the law.” When all else fails, he’s worth a laugh. As one attorney put it, “If Judge Walker knew two languages, he’d be bi-illiterate.”

Most Volatile

Charles Ben Howell

191st Civil District Court. Born: 1925. St. biuis University Law School. Admitted to bar: 1951. Elected to bench: 1980.

In the biggest and the best of district courtrooms, where six giant ceiling fens stir the still air, presides Judge Charlie Ben. A founding member of the CQJ calls the man “a disaster.” County Democratic Party chairman and attorney Bob Greenberg, who insisted that we quote him by name or not at all, says that Howell (a Republican) is “totally incompetent to wear the robe of a judge.”

Greenberg once appealed a case that had been tried in Howell’s court on the grounds that the judge had influenced the jury by breaking down in tears during testimony. “Howell is unable to separate his emotions from the cases he tries,” Greenberg says. “If he’s touched, he’ll let everyone in the courtroom know, completely contravening the legal style of the United States. Everyone does not receive a fair and impartial trial.”

Even when Howell is dry-eyed, he’s been known to go off on emotional tangents. His mercurial nature has garnered him bad marks for some time. He logged time in jail for contempt of court and was reprimanded after a suit was filed against him by the State Bar of Texas.

How Howell managed to get elected is a mystery. Or is it? He probably owes his campaign victory in 1980 to lever-pulling Republicans-although he has never enjoyed the official support of the GOP. Howell’s contest with Joan Winn, a black Democrat, was bitterly fought. Winn had 91 percent of the support of the Dallas Bar; Howell ran ads with her picture, dubbing her an “equal opportunity candidate.”

Attorneys say that Howell is “smart as hell” but lacks good judgment .’One lawyer says, “He knows exactly the right thing to do and does just the opposite.”

Biggest Disappointment

John Mead

Criminal District Court #4. Born: 1922. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar: 1950. Appointed to bench: 1959.

Many people are sad that John Mead doesn’t seem to care about his job anymore. On the other hand, many aren’t: They’re sitting around hoping that he’ll retire. Just about everyone agrees that Mead-who was once the dean of the criminal courts-is marking time.

The mention of Mead’s name, more than any other judge’s, has the effect of splitting lawyers right down the Establishment/anti-Establishment line. Depending on which side you’re on, Mead is either an erudite, “judgely” scholar or an ineffective, patrician snob. One particularly vehement critic went so far as to charge that Mead is “prejudiced against anyone who isn’t a member of the Dallas Country Club.”

That he is well-educated, well-traveled and well-connected cannot be denied. He is married to an heir to the Phillips oil fortune and spends much of his time at their vacation home in Carmel. According to statistics compiled by the district attorney’s office, his total disposition of cases in 1982 was about half that of his peers. He makes no secret that he would rather be in Carmel than in court.

The last time D rated the judges, Mead was off politicking for bigger and better things. He ran a hard-fought campaign for Congress against Jim Collins and lost. Says one trial lawyer, “In my view, [being a] district judge wasn’t John Mead’s first choice for a career.”

Whether he’s battle-weary from running for office or simply bored with being a judge, speculation is heavy that Mead won’t be around for long. “He’s like one of those sad characters out of the Spoon River Anthology,” one lawyer says, “He might have been a big fish in a little pond-if he ever could have come to terms with that pond.”

Longest-Running Feud

Craig Penfold

304th Family District Court. Born: 1942. University of Texas Law School. Admitted to bar: 1968. Elected to bench: 1976.

VS.

Pat McClung

305th Family District Court. Born: 1923. University of Oklahoma Law School. Admitted to bar: 1949. Appointed to bench: 1975.

The legendary feud between Dee Brown Walker and Charlie Ben Howell gave off so much steam that it finally puffed itself out. But there’s another-albeit more polite-little war going on over at the courthouse. It’s between Judges Craig Penfold and Pat McClung.

Dallas’ two juvenile judges get good marks individually (although there are dissenters on both sides) for being sensitive and fair to the county’s troubled youth. But as a team, Penfold and McClung are about as friendly as Rocky Balboa and Mr. T.

First, there’s the question of style. Descriptions we collected indicate that it would be hard to find two judges less alike. Penfold is classy, solicitous and hails from Beverly Drive. McClung is gruff, an Okie and tinkers with airplanes in his spare time. Penfold’s approach to wayward kids is tempered with gentleness. McClung is a hardball. Says one attorney of McClung’s style: “He likes to give the youths a talking-to, and if it impresses them half as much as it impresses me, they’ll walk out of that courtroom scared stiff.”

A personality clash is only part of the story. Family lawyers say that the basis of the feud is a blatant contrast in philosophies. Penfold tends to put stock in the mental health professionals; he “bends over backwards for the state social workers at the Department of Human Resources.” McClung, on the other hand, has an ill-concealed antipathy for people with MSSW (Master of Science in Social Work) degrees. Says one female attorney, “McClung doesn’t have much use for the little ladies at the DHR. In fact, he flaunts his male chauvinism to the point that you could say he doesn’t have much use for little ladies at all.”

It’s been a cold war at the juvenile courts for some time. Things began to really bubble when a former Penfold aide ran in the last election against McClung. It was a bitter, controversial contest; the CQJ didn’t endorse either side. McClung won, but it’s been open warfare ever since.

Are feuding jurists a detriment to the justice machine? Outside of the fact that when one is on vacation, the other refuses to intercede in ongoing matters of his court, probably not. One lawyer even poses the argument that opposing philosophies make for balanced courts. Stay tuned.

Unsung Hero

David Jackson

Probate Court #2. Born: 1942. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar: 1967. Appointed to bench: 1973.

We’ll be honest with you. When you’re talking judges, most of the barbs and kudos go to the big guys in the county and district courts. But there’s another realm of activity in a place few lawyers even see: the pro-bate courts. The job of the probate judge is, to a large degree, thankless. These jurists have the unenviable task of presiding over families during the tragic circumstance of dividing the spoils after a loved one’s death. They hear cases of mental competency and bear the stress of deciding whether or not a person is fit to live in society. Decisions like that aren’t easily left at the office. As one probate lawyer says, “Theirs is a burdensome but essential task.”

All the probate judges generally are looked upon favorably by lawyers who practice in front of them. But Jackson is consistently judged outstanding for being “what you expect in a judge.” During his 10 years on the bench, Jackson has managed to impress many while remaining obscure to most. He is known both as a scholar of the law and as a gentleman, the type “who will sit down and talk things over with you.” One lawyer says, “I’d put David Jackson up against any judge in Dallas County.” We just thought you’d like to know.

Overnight Wonder

Dee Miller

254th Family District Court. Born 1947. Baylor Law School. Admitted to bar: 1971: Appointed to bench: 1981.

When Domestic Relations Court Judge Dee Miller first took the bench, rumors flew that she couldn’t even spell divorce. What she could spell was juveniles; Miller’s experience had been as a prosecutor in the field of child abandonment and neglect.

But Dee Miller is no fool. She buried herself in the voluminous tomes of family law and sailed through a specialty refresher course. She asked questions of the other courts and enlisted the aid of lawyers who would practice before her. One lawyer says, She built a base or support-even among lawyers who went to Austin to lobby against her appointment.”

Judge Miller is known for giving men in divorce cases a fair break, and for not taking any lip off lawyers. She keeps her docket clean and has earned the reputation of a streamliner, sometimes letting attorneys know where they stand before a trial begins. One complaint? “She has a hard time keeping a stable staff because she works too hard.”

Most Tarnished Record

Joe B. Burnett

134th Civil District Court. Born: 1932. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar: 1959. Appointed to bench: 1969.

Hell hath no fury like Henry Wade scorned. Just ask Joe Burnett. A judge of some 14 years, Burnett was all but run out of town on a rail last year when he got trapped in a messy conflict of interest. Burnett had granted an injunction against Wade in favor of a Dallas businessman, who, as it turned out, had given the judge a hefty (more than $42,000) loan. For not disqualifying himself from hearing the case, the State Commission for Judicial Conduct gave Burnett a “private admonishment”-discipline roughly equivalent to a lashing with a single spaghetti strand. That prompted an investigation into the commission by a subcommittee of the Texas Senate.

Naturally, the sordid details were duly recorded by the press. And if the sordid weren’t bad enough, reporters filled the rest of their column inches with tidbits like the fact that some fellow judges think that Burnett takes too much time off from court to go hunting.

The legal grapevine is still buzzing about whether Burnett was framed, desperate or just incredibly naive. Given all the bad press, it’s a wonder he’s able to function in court at all. But in spite of the political smudge, Burnett has a reputation for being fair, a good arbiter, dutiful in his research, and-allegations to the contrary notwithstanding-guileless. If he has a failing, it’s that “he works pretty much nine to five.” In the last election, the CQJ reneged on its endorsement when the issue of Burnett’s conduct began to heat up. But he won another term, anyway. Maybe the next time he runs, the name “Joe Burnett” will work to his favor: Voters will recognize it but won’t remember why.

Best Criminal Judge

Richard Mays

204th Criminal District Court. Born: 1939. University of Texas Law School. Admitted to bar: 1965. Appointed to bench: 1973.

Richard Mays comes on like a cowboy. He wears his lizard-skin boots and gold-plated belt buckle with aplomb. But this gruff, gavel-wielding, y’all-tongued former backfield player for Highland Park is not your average cowhand. He’s by far the best criminal judge on the Dallas district bench.

The last time D called attention to Mays, the jaws of the legal community were still dropping in surprise at the judicial prowess of the former chief deputy from the Henry Wade school. Mays ran the grand jury sin-glehandedly for two years and did his part to earn the reputation that comes with the job. He was expected to become another of Wade’s “hanging judges.”

But four years later, the real Richard Mays is highly respected for maintaining a delicate balance between legalism and fairness. He’s courteous to attorneys and allows each side to speak its piece. One attorney described Mays as “one of those guys with an inner gyrocompass-a sense of right and wrong that guides him and has nothing to do with legal education.” He’s known to be tough on punishment (he sent Bob Hayes to prison), but is aware of the concept of reasonable doubt. It’s always a relief to learn that a man his size doesn’t throw his temper around, but Mays knows how to keep tabs on his courtroom. If he suspects that some young whip-persnapper is trying to take control, he may just rise from the bench, go into his chambers and shut the door. No problem.

Most Likely to Succeed

Ed Kinkeade

194th Criminal District Court. Born: 1951. Baylor law School. Admitted to bar: 1974. Appointed to bench: 1981.

Ed Kinkeade was a dark horse in 1980 when he ran against established criminal defense attorney Michael Byck for the bench of the newly created 10th County Criminal Court. He took his Republican political clout from First Baptist Church, Irving, where his father is pastor, and won the race by a 59 percent margin. Less than a year later, he received an appointment from Gov. Clements and made an ear-popping ascent to a seat as district judge.

The city’s judicial groupies snarled suspicions about Kinkeade’s motives and background. He had zero criminal law experience and barely enough civil know-how to be dry behind the ears. His reputation as a lawyer in Irving was for practicing “don’t-say-no law,” a demeanor understandable in a hungry young lawyer but hardly befitting a judge. He seemed to be a prime example of everything a gubernatorial appointment shouldn’t be.

But now his critics are silent-even embarrassed-at their former lack of faith. Kin-keade is being praised as a pleasant surprise, a hard worker with confidence, strength and style. He doesn’t pussyfoot around with punishment, but is a firm believer in alternatives. He believes that some DWI offenders learn more from picking up after alcohol-related auto accidents than by spending months in prison.

Most of the lawyers on our panel predict big things ahead for Kinkeade. But they suspect that he may not stay a judge forever: “He has real political possibilities.”

Most Unwelcome Visitor

James F. McCarthy

Visiting Judge. Born: 1920. SMU Law School. Admitted to bar 1948. Appointed to bench: 1963.

The last time D rated the judges, Jim McCarthy sat on the district bench. Now he’s retired, but his courtroom style is not. The man D labeled as “too busy playing Don Rickles to play judge” is now a roving jurist.

Of all the visiting judges brought back from retirement or defeat at the polls, McCarthy seems to be the most dreaded. When he served, he got bad marks for being consistently insulting to lawyers. He gets worse feedback now. To wit: “He is rude, bad-mannered and obnoxious.” “Jim McCarthy didn’t like being a judge when he was on the bench, and there’s no justification for bringing him back now.” In the 1981 Dallas Bar Judicial Evaluation Poll, only one notoriously bad judge got a worse response for judicial temperament and demeanor.

The subject of visiting judges is a hot topic. Lawyers don’t like them. And understandably: There’s little certainty in trial law; it is difficult-if not impossible-to predict with any accuracy the outcome of a case. Knowing the judge he’s docketed for can help a lawyer gauge the odds. Unfortunately, what you see isn’t always what you get.

But in the real world, visiting judges keep the system chugging when the designated jurist is away from court. And there’s no limit to how much time a judge can take off. As elected officials, judges are accountable only in the sense that they must get past the voters every four years. Some attorneys complain that the older judges, especially, fall back on the practice of regularly bringing in visiting judges. They do so in the name of docket control, “but actually it’s to help these guys augment their retirement pay.”

Most Innovative

John McClellan

Marshall

14th Civil District Court. Born: 1943. SMU Law School. Admitted to ban 1976. Elected to bench: 1980.

When John Marshall ran for judge in 1980, he came out of nowhere to defeat veteran Fred Harless in the 14th Civil District Court. He was not well-known except for an occasional rumor-like the one claiming that as a Muenster, Texas, municipal judge, he wrote opinions in traffic cases. His win was largely attributed to the fact that the name “John Marshall” has a familiar, judicial ring.

Since talcing office in January 1981, Mar-shall has been something less than obscure. He has tried all sorts of novel twists to administering justice, some of which have been more successful than others. He abolished the time-honored practice of hearing pretrial motions one day a week. His hearings are set every morning at 10-minute intervals from 8:15 to 9. He claims that the quality of motions has improved while the quantity has decreased. “Only a lawyer who’s serious about a motion is going to come down here at 8:15,” he says.

But another innovation in docket control backfired. To his credit, Marshall admitted his mistake. He had decreed that until a case was disposed of, it would come up on the docket every week. That way, no lawsuit could fall between the cracks. But as one lawyer puts it, “That’s fine in theory, but some weeks he would have 150 cases set for trial.” A number of letters from lawyers convinced Marshall to find a better way.

If Marshall has anything to say about it, he’ll become the state’s first video judge. An experimental trial staged at an SMU video facility convinced him that pre-taped trials played to a jury are the wave of the future. Courts could increase their jury trials, he predicts, from 30 or 35 a year to more than 400 by adapting an all-video format. “Historically,” Marshall says, “institutions that don’t adopt the technology around them tend to ossify and, eventually, to disappear. That could happen to the courts.”

Pontificating is a characteristic of Marshall, too. “He loves to hear himself talk,” is an observation voiced often by those who work in his court. Marshall has also been criticized for what some people view as his pretentious habit of wearing the striped robe of academe. Despite criticism, Marshall seems all too aware of the follies of pomposity: “I’ve seen a lot of judges fall prey to the foible of taking themselves too seriously.”

The Great Black Hope

H. Ron White

301st District Court. Born: 1941. Howard University Law School. Admitted to bar: 1972. Appointed to bench: 1983.

When Ron White was appointed by Gov. Mark White in June, he was expected to be the kind of judge Dallas didn’t have: bright, hard-working and black.

White isn’t taking the honor lightly. He bemoans the fact that there is “an absolute void of black representation” in the Dallas judiciary (Berlaind Brashear, who consistently rates at the bottom of the Dallas bar polls, is the only other black county or district judge), but emphasizes that one person won’t solve the problem. “Although maybe if I do a good job, people won’t be so apprehensive about electing them.”

So far, White is doing a good job. He’s impressing the legal community with his intelligence, and his experience as counsel forAtlantic Richfield gave him some good business sense: “He runs his courtroom a littlelike a corporation,” one attorney says. “He’sresponsible to his stockholders.”

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.