Rodney Dangerfield likes to talk about the time he looked up “ugly” in the dictionary and found a picture of his mother-in-law.

By the same logic, a dictionary entry for “conglomerate” should carry a picture of Jim Ling, or at least a cross-reference: see also Ling, James J. Through the Sixties and early Seventies, conglomerate-in Texas and throughout the country -meant Jim Ling, creator of the huge Dallas-based Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV).

How big was LTV? Massive.

At its peak in 1969, Ling’s company controlled Wilson, the nation’s largest producer of sporting goods and its third-largest meatpacker; Jones and Laughlin, America’s sixth-largest steel company; Braniff, the eighth-largest airline; and Vought, the eighth-largest defense contractor. Toss in a string of other companies with their innumerable subsidiaries and you have Ling-Temco-Vought, at the time the 14th-largest company in America.

How big was LTV? So big, some say, that only the U.S. government was big enough to stop it. Calling LTV “a force destructive of competition,” the Justice Department filed an antitrust suit to force LTV to give up Jones and Laughlin. Ling, not his lawyers, devised a settlement to placate the feds.

How big was LTV? So vast, according to some observers, that not even the man who created it really understood its inner workings. And Ling, an idiosyncratic genius, was finally caught up in a swirl of circumstances-market reversals, government harassment, personal conflicts with associates-that led to the famed Palace Revolt of 1970, when Ling was booted out of the company he built.

Since his LTV days, Jim Ling has been anything but idle. Immediately after the Palace Revolt he formed Omega-Alpha Inc. as a comeback attempt, but that company filed for bankruptcy in 1973. Since then he’s formed other companies, sold his huge $3.2 million house and moved to less opulent quarters, and is on the way to conquering a rare and debilitating disease that left him virtually paralyzed for several weeks last year.

His current business venture, Matrix Energy, is nowhere near the size of brontosaurian LTV-and that’s just fine with Ling. His work seems to be thriving; he’s happy, and, as always, his mind is humming with new ideas. For many, he will always live in the giant shadow of his former self, and he’s learned to accept the public’s penchant for the comparison game: Yeah, that’s fine, but it’s not LTV. But that’s the public’s problem. Jim Ling doesn’t waste much time looking back.

James Joseph Ling was born in 1922 in Hugo, Oklahoma, the son of Henry William and Mary Jones Ling. Jim Ling’s grandfather had been a Bavarian immigrant, and Henry Ling was a Roman Catholic convert. With World War I a recent memory and anti-Catholicism on the rise, Henry Ling faced constant subtle and not-so-subtle attacks from local bigots-in particular the members of the train crew with whom he worked as a fireman. Finally, harassment led to violence; the elder Ling killed a fellow worker in a fight. Pleading self-defense, Ling was acquitted, but he carried the burden of guilt for the rest of his life. A few years after the incident, Henry Ling gave up on the world and joined a Carmelite monastery.

When Jim Ling was 11, his mother died of blood poisoning. His older brothers, Michael and Charles, were sent to Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Town in Nebraska. Jim went to live with an aunt in Shreveport, Louisiana, and began to discover his intellectual gifts at St. John’s College, a Catholic boys’ prep school.

“Somewhere somebody got the idea that I’m a publicity hound,” Ling says. The legend has grown. Some parts of the myth have strayed so far from the truth and been repeated so often that Ling hardly bothers any longer with setting the record straight.

Ling used to bristle, for instance, at being called a high school dropout. The label is accurate only in the narrowest sense. True, Ling has no high school diploma, though he had enough credits to graduate the year he left school. But St. John’s would not let him graduate early, and he was getting bored with school. For a time he had flirted with the notion of attending Notre Dame and entering the priesthood. But, Ling says, he reached puberty about the same time -“and puberty won out.” Ling left school and became, in his own words, a “bum” for a while.

In the early Forties, Ling found himself in Dallas, where he became an apprentice electrician to a local contractor. While still in his teens he married, and when he was 21 his first child was born. Hoping to make his family financially secure before he went to war, Ling worked as an electrician during the day and held another full-time job, in an aircraft plant, at night, thus earning a draft exemption.

Ling joined the Navy in 1944 and was sent to electrical school in Mississippi. There he found himself in a class of 200 men, most with high school or technical school backgrounds. He finished second in his class. “That made me feel comfortable, from an intellectual viewpoint, that I could compete,” Ling says.

“I could make a case that I might have been a better businessman had I gone to college,” Ling says. “Or, 1 could make a case that I might have gotten into a structured environment that wouldn’t have allowed me to do what I wanted to do. But I’ve been a voracious reader and I’ve always done my homework.”

In late 1946, Ling was discharged from the Navy and decided to go into business for himself. With one truck and $2,000 worth of war-surplus electrical equipment, he began the Ling Electrical Company. He barely made expenses the first year but doubled his volume to $200,000 in 1948 and doubled it again in 1949, branching out to work on hospitals and larger operations.

By 1954, Ling Electrical was grossing more than $1 million a year and had contracts all over the Southwest. The business had grown beyond needing Ling’s everyday attention so he was playing a lot of golf (then, as now, a passion) at Preston Hollow Country Club. He was a bit bored, and he was thinking about a move that would mean a quantum jump in his career: going public.

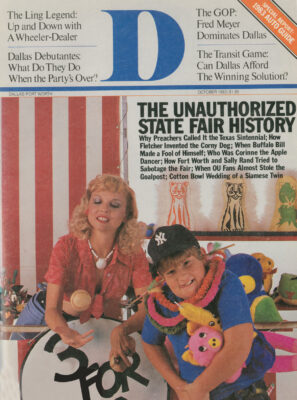

Ling was unable to persuade Dallas investment bankers to back his stock offering, but he formed a board of directors and with their support got the authorization to issue one million shares of stock at $1 a share. To push the new corporation, Ling Electric Inc., Ling set up a booth at the Texas State Fair to hand out copies of his prospectus. Public sale of Ling Electric shares brought in some $800,000, and Jim Ling was on his way to becoming an American legend.

Ling made several acquisitions in those pre-LTV days, the biggest coup being the purchase of the Altec Companies, makers of commercial sound systems. Altec was larger than all of Ling’s holdings at the time, had a sound balance sheet and considerable nationwide prestige. Realizing the clout of the Altec name, Ling changed his corporation’s name to Ling-Altec Electronics Inc.

Even in those early days, the name of Ling was taking on a certain magic, says Joe McKinney, a Ling associate in the early Sixties and now president of Tyler Corp. And there was another allure: The electronics industry itself, because of the public craze for “space-age” technology, seemed very much the wave of the future. McKinney’s first impressions of Ling were echoed by many who met him and invested in him: “I was spellbound from the beginning by his energy and imagination.”

In 1960 came Ling-Altec’s merger with Dallas-based Temco Inc., makers of military aircraft. The move looked particularly promising since Temco had landed a hefty government contract for work on the Corvus missile. Also, the merger helped Ling reach one of his personal goals, a place on the Fortune 500 list of America’s largest companies. Soon after Ling-Temco was formed the government canceled the Corvus contract, but by that time Ling was already concentrating on the acquisition that would make his name synonymous with conglomerates: the Chance Vought deal.

Chance Vought was, in a sense, Ling’s Rubicon. Once he had acquired this respected old-line New England company – which had developed the Navy’s World War II Corsair jet, the Crusader fighter plane and the Regulus missile – Ling was a national power to be reckoned with. And locally, the battle for Chance Vought would color attitudes toward Ling for two decades. Jim Lawson, a Ling associate for 11 years, says that many people in Dallas and elsewhere read the struggle this way: “An upstart company led by an upstart entrepreneur trying to take over blue-blooded Chance Vought.”

Chance Vought executives such as Robert Detweiler were among the leaders of Dallas society at the time, and the company gave generously to local civic and cultural organizations. Ling must have known that his attempt to take Chance Vought would make him some enemies, but the prize was worth the risk. Chance Vought’s sales were running at more than $250 million a year, almost double Ling-Temco’s. The acquisition would mean moving even further up the Fortune list.

Some of Ling’s investment bankers balked at the deal, but Ling persuaded his Ling-Temco board to put $10 million -a figure that represented most of the company’s working capital -into a fund for buying Chance Vought stock. In addition, Ling went deep into debt to raise money for the attempt, borrowing $6 million from insurance king Troy Post, who would later figure in Ling’s demise at LTV.

By early 1961, Ling and Ling-Temco had garnered more than 10 percent of Vought’s stock, at which point the Chance Vought management grew uneasy. A letter was sent to Vought shareholders that painted Ling as a vicious opportunist; in return, Ling increased his offer for 150,000 Vought shares to $43.50. Chance Vought, in an obvious delaying action, filed a civil antitrust suit against LingTemco. The suit was later dropped, but the government threatened its own suit, which Ling insists was “purely politically motivated.” To this day, Ling believes that he was on Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s “hit list” because he had supported Lyndon Johnson rather than John Kennedy for the presidency in 1960.

In March of 1961, Chance Vought yielded to the inevitable. Ling had bought up almost 40 percent of Vought’s stock, so a merger was arranged. Eventually, the government suit was decided in favor of Ling; and Ling-Temco-Vought, one of the most personal conglomerates ever constructed, was born.

The battle for Chance Vought was over, but Jim Ling remained in the public eye. That year he built a house in North Dallas – quite a house indeed. As Esquire magazine put it, “What do you do when you have laid out more than $3 million for land, buildings, fountains, statuary and paintings, marble floors, 24 gold Louis XV chairs, monumental bathtubs, a Japanese teahouse and a water bill that would run to $700 a month in the dry season?”

Answer: If you’re Jim Ling, you stay visible. Whether or not you want publicity, you get it. And you continue to build your empire. Ling’s 1964 Project Redeployment, considered a master stroke in American financial history, created three new publicly held corporations out of Ling’s parent company: LTV Aerospace, Ling-Altec and LTV Electrosystems (now E-Systems). Stockholders held fewer than 125,000 shares of each new company while LTV bought more than a million shares in each. In other words, the LTV offshoots both were and were not publicly owned. If one of the divisions lost money, Ling hoped their “separate” status would keep the public from losing confidence in the other branches.

Project Redeployment worked. Ling’s biographer, Stanley Brown, calls the favorable public response to the project “an essentially irrational behavior pattern” since none of the companies was really changing at all, “redeployment” or not. All would be managed as before and would produce the same goods and services as before. What was different was that people would be paying considerably more for the stock of these LTV “children” than they had before. “LTV would literally create new borrowing power out of the air as the price of subsidiary shares rose on the stock market,” Brown wrote.

Ling’s plan bewildered some of his associates and much of the financial community, but there was little arguing with his success. Those who know Ling well say he’s always been hard to follow because of the lightning-like pace of his thinking. “He does take a lot for granted, and he skips a lot,” says Jim Lawson. “When he’s conceptualizing, he can lose people in a minute.” Securities lawyer William Tinsley, a Ling associate since the LTV days, recalls meetings in which directors would nod in apparent understanding as Ling outlined another innovative plan. Then, when the meeting broke up, some frustrated director would turn to Tinsley or someone else with a reputation for deciphering Ling: “Damn it, what did he say? Explain it to me.”

When Ling’s mind is in high gear, he can range over his 40 years of financial wizardry and confound a listener with his canny recombinations of assets, possibilities and personnel. Chatting casually about the new Aerobics Center and the work of Dr. Kenneth Cooper, Ling abruptly segues into a long reverie involving Cooper and Wilson Sporting Goods and….

“We used Ken Cooper as an inspirational guest speaker at LTV in 1968 or 1969,” Ling says. “We looked carefully at trying to tie Cooper and the Aerobics Center into Wilson. You’d set up a number of tennis and health centers and sell your Wilson merchandise there. But I’m afraid that due to a lot of diversionary activities, that thought was never pursued. I don’t remember the reasons why, but two or three years ago I came across a memo delineating the concept. I’m not sure Cooper would ever have fit into that structure, either. But the real estate [for the tennis centers] would be a holding ground. There’s not much involved in building tennis courts, but it would have been a great way to inventory real estate. You’d buy three or four acres in a growth area, and then if tennis sort of phased out…. It would have been a hell of an investment.”

And on and on. For a moment, the listener is carried along on the crowded stream of Ling’s thought. He sounds as interested in the plan as he must have been 14 years ago when, for a fleeting moment, the deal might have been plausible. Of course, Ling knows that the time for such a venture is long gone, but in a strange way this immensely practical, detail-conscious man shares something with the scholar and the pure scientist: He enjoys the play of mind over ideas, even when the creative process adds nothing to anyone’s balance sheet. Had the circumstances of his life been vastly different, it is not hard to imagine Ling as a college professor of European history or medieval philosophy, debating arcane points with his students. “You can always feel that restless mind of his,” says Joe McKinney. “He’s always prowling like a tiger, nosing around those chunks of ideas.”

In mid-1966, Ling’s fertile mind had been occupied with moving LTV away from its heavy dependence on government military contracts. Ling remembered the Corvus missile cancellation and knew that no thriving company could count on government largesse forever.

Enter Project Touchdown. Ling set his sights on Wilson and Company Inc., the third-largest meatpacking company in the United States. Wilson Sporting Goods was the world’s largest, and its pharmaceutical operation was attractive, though small. Wilson’s stock had never sold at more than $57 a share, so Ling pitched his tender offer at $62.50 for 30 percent of Wilson’s outstanding shares. Wilson management fought back with a counteroffer of a 50 percent dividend and an increase in the cash dividend. But Wilson’s brass owned very few of the company’s shares outright so they could do little other than ask shareholders to cooperate. Most did – with Ling. Project Touchdown scored big, and Wilson was redeployed into Wilson and Company (the meatpacker), Wilson Sporting Goods and Wilson Pharmaceutical and Chemical Corporation – “Meatball,” “Golfball” and “Goofball,” in stockmarket slang.

Again, as with the Chance Vought acquisition, LTV was the smaller fish swallowing up the big fish -a veritable whale in this case, since Wilson’s 1966 sales were close to $1 billion.

That year, Ling was invited to speak to the students of the Harvard Business School. A young man who had obviously done his homework asked Ling why he was buying into Wilson when, after all, the meatpacking business had less than a 1-percent profit margin and was subject to the vagaries of weather, cattle disease, etc. “I told him he had missed the entire point,” Ling says. “We didn’t buy the meatpacking business to be in the meatpacking business. We bought it because it was an asset play.”

The play succeeded beyond anyone’s dreams -except, of course, Ling’s. LTV stock, which had traded as low as $16.75 in 1965, soared to $169.50 in early 1967. Ling’s own LTV stock was worth more than $70 million.

Experts and interested laymen will always disagree about just when Ling’s star began to fall at LTV. Jim Chambers Jr., former chairman of the board of the Dallas Times Herald and an LTV board member for three years, believes that Ling overreached himself after the Wilson triumph. “He’s a tremendous entrepreneur but a poor manager,” Chambers says. “It [LTV] got so big and far-flung that it was hard for him to continue his entrepreneurial drive and manage well.”

John Dixon, now chairman of the board of E-Systems and a vice president of planning under Ling at LTV, agrees with Chambers. “Ling was not as interested in the managerial aspects,” Dixon says. “He’s a putter-together. He loves the challenge of doing new things. He’s not so good at the routine of day-to-day management.” Says Chambers: “Had he stopped with Wilson and consolidated his company without further growth, he would still have a damned big company and he’d still be running the thing today.”

Perhaps. But those who know Ling cannot imagine his stopping and consolidating. He was Ulysses, not Telemachus, and he needed newer worlds to conquer. Or, to change the metaphor, Ling was the pioneer forever striking out to blaze new trails into the financial wilderness. He’d carve out a clearing in some new place no one thought he could reach. But let someone else build the general store and wait for the schoolmarm.

Why? What drove Ling? Not the money or the executive perks such as the company jet and the Fifth Avenue apartment and the sprawling ranch for LTV’s “offsite” meetings. “To Ling, money is like a hammer to a carpenter,” one friend says. “It’s something he can create with. A plane was just something to get him somewhere to pull off a deal.” A former Ling associate recalls seeing Ling work around-the-clock in New York hotel rooms, keeping five assistants busy while he researched and phoned, shaping a new merger. “He wasn’t just sitting up there drinking champagne and living it up. He might be in his pajamas until one in the afternoon, but he’d be working like hell.”

Why, then? “He’s got an insatiable appetite for growth,” says Jim Chambers. “One acquisition triggered the appetite for another. Guys like him never think they won’t be able to do one more deal, reach for one more brick. Finally, he just reached the barrier.”

According to many Ling watchers, that barrier was made of solid, durable Jones and Laughlin steel and specially reinforced by the U.S. government.

By 1967 LTV sales exceeded $1 billion. Ling tried that year to buy Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Co. of Milwaukee and the American Broadcasting Companies, but the boards of both companies turned him down, and his strategy that year ruled out any forcible takeovers -“hostile mergers” in business parlance. Ling did buy Troy Post’s Greatamerica Corporation, which brought Braniff Airways and National Car Rental into the LTV fold.

And then, looking around for another redeployment target, Ling found Jones and Laughlin Steel of Pittsburgh. Ling-Temco-Vought made a tender offer for 63 percent of J&L at $85 a share, considerably above J&L’s market price of $50. To assure officials and employees of J & L that he was not a “corporate raider” out to break up the company and sell its assets, Ling even promised to put the stock LTV would buy into voting trust for three years. During that time the majority of the J&L board would be made up of J&L appointees, thus assuring that matters would remain status quo with the company for the foreseeable future.

Ling paid more than $425 million for J&L, the largest cash tender offer ever made to that date. He has been endlessly second-guessed about paying so much for the steelmaker, but his board at LTV approved the deal without qualms. J&L’s average earnings were approximately $40 million a year, so the price did not seem terribly high in that context. But much of the purchase was made with borrowed money and much of it would have to be repaid within two years. Then, despite rosy projections of earnings from the J&L people, the company went into a nose dive amid a general downturn in the market. And then, things really got bad for Ling.

While he had been wrestling with the problems of Jones and Laughlin, an anti-conglomerate mood had been building in the country. The incoming Nixon Administration, sympathetic to the pleas of corporate “fat cats” who feared that their companies might be swallowed by an LTV, a Litton or a Gulf & Western, announced a crackdown on conglomerate activity. Richard W. McLaren, the assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, pledged to stop the growth of the giant corporations.

Angry, Ling placed two-page advertisements in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal in March of 1969. Titled “Plain Talk From LTV,” the ads defended LTV against McLaren’s threats in blunt language that worried some LTV officials. Later that month, the word came down: The Justice Department planned an antitrust suit to force LTV to divest itself of Jones and Laughlin. LTV was at that moment tendering for the final outstanding shares of J&L stock, so the spectre of an antitrust suit could not have been raised at a worse time.

No one, Ling included, has ever claimed to understand the government’s rationale in the LTV case. Ling-Temco-Vought was called “a force destructive of competition,” but Ling was never told just how his company was bad for free enterprise. Traditionally, government trustbusters have moved against companies owning more than one subsidiary in the same field, arguing plausibly that a. company’s left hand is not going to fight very hard to keep profits out of its right hand.

Such reasoning did not apply to LTV, Ling says. “It was absurd. The only possible conflict might have been with the cars we were leasing [National Car Rental]. Apparently they thought we might get some kind of deal going selling steel to the auto makers, but that wouldn’t stand up in court. We were in the process of selling National at the time.”

Ling was confident of winning if the case came to trial. “I’d had another political lawsuit before [with Chance Vought], and I wasn’t afraid of it. I happen to have a damn good understanding of antitrust law, plus we had legal opinions galore stating that the government couldn’t move against us just because we were big.”

Hoping to prevent a shareholders’ panic, LTV asked for an expedited hearing. Nothing could be worse than for the corporate body of LTV to twist slowly in the wind for months while the price of the stock dropped. And that’s exactly what happened. The Justice Department promised LTV a speedy hearing. “Then they came back with interrogatories that would have taken 200 man-years for us to answer,” Ling says. “So I knew they weren’t serious about going to trial. That’s when I made the decision to settle.”

Ling describes his compromise agreement with the government as “a ludicrous settlement for a ludicrous lawsuit.” He sent a message to Attorney General John Mitchell [using an emissary who is now one of Texas’ best-known businessmen] offering to divest LTV of Braniff and Okonite, a maker of wire and cable, instead of Jones and Laughlin. Ling had been wanting to sell these companies for some time, so he was relieved when Mitchell’s answer came back: “Throw the bureaucrats a bone.”

The settlement was arranged, but the damage had been done -and it was serious. LTV stock had dropped after the J&L tender offer; now, after weeks of much-publicized wrangling with the government, the company saw its stock plunge even lower, to $20 per share – down from $29, its high that year -and no end was in sight. That unprecedented decline in LTV’s value would be a major factor in Ling’s undoing.

Perhaps worst of all, the government hampered LTV in its dealings with Jones and Laughlin. J&L dividend payments of $16 million – 80 percent of which would have gone to LTV -were halted. “They felt obligated,” Ling says sarcastically, “to protect the 20 percent of capital reserves not held by us -the pontificating sons-of-bitches.” In addition, LTV representatives were not allowed a voice on the J&L board while the antitrust investigation was in progress. In effect, Ling had no control over his costliest asset.

For years, Ling toyed with the idea of writing an autobiography, saying that the full story of his final days at LTV had never been told. Now he says he’s abandoned the idea, so the truth of what happened in the Palace Revolt may never be disclosed. It’s completely possible that Ling himself holds only part of the puzzle. Others holding clues are Robert Stewart, then chairman of the board of First National Bank of Dallas; E. Grant Fitts, president of Gulf Life Holding Company; and Troy Post, who sold Greatamerica Corporation to LTV.

The convoluted financial dealings that linked these men to Jim Ling are too complex for summary. But it would not oversimplify to begin with the Fives of 88. When Ling acquired Post’s Greatamerica, he arranged a stock swap in which Greatamerica shareholders would receive 5 percent debentures (similar to bonds), payable in 1988, in exchange for their Greatamerica common stock. Troy Post wound up with about $100 million of the Fives of 88 in exchange for his 20 percent of Greatamerica. The value of the Fives would fluctuate, of course, in relation to the value of LTV stock.

Fitts’ Gulf Life Holding Co. had bought Greatamerica’s insurance companies from LTV. Both Post and Fitts stood to lose heavily if LTV stock dropped in value, which it did during the J&L antitrust problems. Post also owed Stewart’s First National Bank several million dollars, his loan secured with the Fives of 88. If the Fives dropped far enough, Post’s loan could go “under water.”

Stanley Brown, author of Ling, believes that one of the principals-Post, Stewart, or Fitts – suggested demoting or ousting Ling, perhaps reasoning that such a “public execution” would rekindle public faith in LTV. Inspired by the company’s new leadership, the market for LTV securities would strengthen. The Fives of 88 would then rebound to something like their original value. Thus, Ling would become a highly visible scapegoat to blame for the company’s problems -after all, he had led them into the Jones and Laughlin quagmire.

So, after a week of meetings and rumors of meetings, the Palace Revolt came to a head. Different accounts exist of what happened at the special board meeting on Sunday, May 17, but it ended with Ling’s demotion and the resignation of several pro-Ling directors. Robert Stewart became chairman of the LTV board. Later shuffles and intrigues reduced Ling’s influence to almost nothing, and he soon faded out of the picture.

Sources close to Ling disagree as to whether the Palace Revolt was a dispassionate business decision or the result of anger, jealousy and other emotional baggage carried by the principal players. Jim Lawson believes that there were more personality conflicts than sound business reasons at work during the Revolt. But Jim Chambers, then an LTV board member, disagrees. “There was not a damn thing personal in it,” Chambers says. “I never saw any animosity, just great regret and real sadness.”

“I really believed that they’d see that this routine wouldn’t solve any of the problems they envisioned,” Ling says. “I didn’t think of it personally at all. I’m still closely allied to one of them, and I have no grudges against the other. They just didn’t know what the hell was going on, really. They couldn’t see the big picture.”

Ling dislikes playing what he calls “the game of ifsy,” sifting through the cold ashes of the past in search of what might have been. He’s not bitter about the manner of his leaving the company he built, though he admits to “a special possessive feeling” about LTV. He’s aware that some of his problems can be attributed to his own personal style.

“I never meant to be arrogant or rude,” Ling says. “But I’m sure there were times when I appeared that way. I don’t mean to say that I didn’t take them seriously…. I took every director seriously, but 1 thought they were well-informed enough. I can be provoked, especially when someone has not done his homework.”

“My mistake, I’ve been told many times, is that I perceive people knowing what I know when in fact they don’t,” Ling says. He believes that he spent ample time keeping his board members informed but says that some members just did not assimilate the information. “Some of them wanted to spend a lot of time in a board room rapping about it. 1 liked to have a general discussion but I didn’t want to reinvent the wheel at the board meeting.”

Ling’s greatest challenge since leaving LTV has not been financial but medical. Slightly more than a year ago, Ling and his wife, Dorothy, returned from a vacation in the Carmel Valley of California. A day or so later, Ling jogged his normal three miles, then discovered that his calves were unusually sore. He also had a fever blister and a slight fever for a day. On the Friday before Labor Day, his legs felt heavy. Then came a tingling sensation that started in his finger tips and ended in his wrists. He clumped around the house “like a Frankenstein,” moving only with difficulty.

By six that afternoon, when he tried to get out of a chair, Ling found that his locomotion was almost gone. He slid out of the chair, unable to stand or crawl. The next morning, he was driven to Presbyterian Hospital, where he was diagnosed as having Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare disease that attacks the nervous system. Guillain-Barre s incurable; the disease comes on without warning and runs its course, causing varying degrees of paralysis, and, often, death.

Ling’s case was severe. Within a week he was completely paralyzed, requiring a tracheotomy, a respirator and intravenous feeding. At the peak of his illness he could move only his left eyelid. His heart went into wild fibrillations, once racing at 180 beats per minute. When Guillain-Barre is this extensive, the fatality rate is approximately 65 percent from the side effects: the heart problems, bladder infections, pneumonia.

“I had all of them,” Ling says. “At one point a priest came in and gave me last rites. I really didn’t think I was in that tough a position, though. I knew I was in damn good shape and figured I’d beat the law of averages if anyone was going to beat it.”

After three weeks, Ling’s paralysis began to recede. After six weeks in the hospital, he was eating cereal and standing with the aid of a slant board. Now, more than a year later, he walks and shuffles two miles in 32 minutes, but he pays the price -a burning sensation in his feet and ankles. His feet are still partially paralyzed and extremely sensitive to pressure, so he wears house slippers around the office. At times, a fine tremor runs up his arms.

Ling undergoes five hours of therapy a day; as his atrophied muscles come back to life, he must drive himself to regain his strength and flexibility. “I feel like I have a thousand rubber bands wrapped around my legs,” he says. “Occasionally, one of the bands will pop off and I’m a little looser, more flexible.”

Always a man of strong self-discipline, Ling is rigorous with himself now, refusing to live the life of a semi-invalid. Getting into the shower, for instance, presented major problems. If he began to slip, he could not move his feet to recover his balance. The glass doors of the shower were a constant danger. Until a few months ago, Ling braced himself on a stool placed on a rubber mat. Then it oc-cured to him that a wet towel on the shower floor would do as well. “That removed another crutch,” Ling says.

Ling does not talk much about his current venture, Matrix Energy. An oil and gas exploration company with reserves of more than $100 million, Matrix bought the L.G. Williams Oil Co. in 1981. Williams, of Oklahoma City, has interests in some 150 producing wells in Texas and Oklahoma and thousands of minority investors in the wells. Currently, Matrix is involved in a “roll-up” operation with the many Williams investors, offering stock in Matrix in exchange for their interest in the wells. Ling and Lonnie Williams, his partner, have plans for taking the company public within a few months. “Then I’ll be eager to blow my horn about lots of things,” Ling says.

Ling says he is not interested in owning another company the size of LTV, and most who know him take him at his word. “Yes, he suffers by comparison with himself,” says Jim Lawson. “But so did Henry Ford. He didn’t keep coming up with more innovations. Ling doesn’t even aspire to those heights anymore.”

Another friend of Ling’s has a different view: “I think if he had an opportunity, he’d try to take LTV again. He could stay private with no zebras [Justice Department officials] to change the rules on him, but his instinct to vindicate himself is so strong that he’d try to do it.”

“Jim wants to do something noteworthy, but he’s not trying to get back toLTV size,” says William Tinsley. Still, itwouldn’t be wise to bet that Jim Ling willever stop building, planning and gambling. Guillain-Barre has slowed his body- if only temporarily -but not his mind.”He’s going to be the same guy,” says afriend. “He’ll run awhile, then he’ll pause.This is a pause.”