I HAVEN’T MET him yet, you understand, but he’s out there somewhere, my third husband. Once seven or eight years ago, not long after my second husband and I were married, I heard news of him at a party. After the drinks and hors d’oeuvres, after dinner and coffee, after brandy and conversation, one of the other guests read palms. Peering into the intricacies of my hand, she brushed her long, dark hair back over her shoulder, moved in closer for a second look, and there he was, hovering guiltily in a crevice between lifeline and love line — my third husband.

He should have felt guilty, uninvited and obtrusive as he was. No one wanted him around. It was hard enough for my mother, father, children, friends, to get used to the idea of my second husband, for heaven’s sake, without this third specter — let’s call him Trey. From their point of view, enough is enough.

Nevertheless, sometimes on quarrelsome Sundays or on evenings when my husband is working late, I gaze deeply into the lines that cross my hand and I can make out a charming little figure slouching back against the mound of Venus, debonair yet patient, waiting for the cue for his buck and wing.

Will that cue ever come? I hope not. My present husband and I are, knock on wood, happy. We have a good thing going and we know it. But I am aware that about half of the Dallas marriages made in the year we were married, 1974, end in divorce. So I can contemplate Trey with curiosity, even with a chilly pleasure. What he stands for is my American faith in marriage.

The most beautiful woman I know said to me once, “In my next reincarnation I won’t have to get married; I’ll have outgrown all that.” She’s a decade older than I am and several decades wiser, and I have no doubt she can envision such a state. I’m not ready for it. I love marriage, love being married, and I have been married to one person or another for the past 24 years, from 1958 on. My present husband likes to say that I was single for 10 minutes once. Actually it was eight months, from October 1973 to May 1974. My mother knows the number of hours.

Both times I married to please myself. The first time I was a rebellious child, marrying another rebellious child. That it lasted for 15 years and ended with affection is a testimony to both our characters.

The second time I had been through years of alienation and anger, and had endured a miserable and lengthy separation. Though I steadfastly resisted divorce till it was unavoidable, for almost four years I had felt single and was even beginning to see the charms of the single life.

Not that I ever enjoyed being, or even really was, a “single.” All the machinations of the singles set, if there is such a thing, were impossible for me. I’ve never been to a bar alone in my life except to meet a friend, haven’t picked up a male since I was on the beach at 18, and in my loneliest moments have never resorted to computer dating, personal ads or such tricks on fate.

Just “dating” was hard enough. The absurdity of a mother in her 30s going out on “dates” crippled my imagination and pride. The few men I saw during that time I prevented from coming to my house, fearful of the reactions of my children. During the long separation, I kept up a front as well as I could — to the kids it was one of cheerful independence; to my parents, one of marital solidarity. So I’d meet my male friends at a restaurant or a bar, and go home by myself in my own rattletrap car.

After a while that felt fine. Getting, at last, the long-delayed divorce helped, too. Stronger and more capable than ever before, I came to like myself. My life was in order. My two children and I were living together peacefully. I had friends, work I loved, a feeling of control.

A letter from my friend Jan, herself remarried and living in Connecticut, put the pleasure of single life very well.

Dear Jo,

It was so nice talking to you and I wish I could be sitting there right now and we could go on for hours. It should be that you could just go and find more friends but it doesn’t seem to be that simple for me. I guess the happiest time I can remember was when you lived next door. Special friends make all the difference in my life.

I would like to know all about you and how you are feeling. I envy you your ability to earn a good living and I think that must be helpful in adding to your feelings of security. I think, Jo, that being divorced was difficult for me because of my emotional insecurities and primarily because of my financial problems, which were horrendous.

I think this can be a good time for you to weed things out and perhaps to have a few nice experiences and times that you are not able to when you are married. I think that not answering to anyone is a very definite plus. I don’t know about Dallas but up here there are so many activities for people who are no longer married that you could be busy all the time. And I mean things that are interesting, not just places to meet men. I know many women who have been living alone with their children for some time and seem to be functioning very well.

You shouldn’t be at all worried if you want to remarry. I remember my analyst saying to me once, “You must know somewhere deep down that you are far above the ordinary, and if you want another husband you’ll have one.” If you will excuse me for quoting my doctor to you, I must pass on the same words. Wait for some nice man with white hair who knows who he is and isn’t struggling to prove anything.

Meanwhile do let me hear from you and give love to Erin and Winton. And of course to yourself. Keep busy and happy, hear.

Jan

Actually, Jan, who had never worked in her life, had conceived a somewhat grandiose idea of my status as a university teacher. That fall of 1973 I was making $8,000 a year, hardly sufficient for food, rent and kids’ shoes, much less the twice-a-week psychiatrist Jan was seeing. Such stabilizing as I got, probably not enough, I managed myself, with a little help from my friends. The regular child support that began with the divorce decree helped more than a little, but things still weren’t easy.

No doctor had to tell me that I could marry again if I wanted to. I sensed that my days as a married woman weren’t over, and sometimes put myself to sleep at night with dreams of Jan’s white-haired man, nice and rich, who would see me as the essence of springtime delight and take me and the kids around the world.

Build thee more stately mansions,

O my soul,

As the swift seasons roll!

Leave thy low-vaulted past!

Let each new temple,

nobler than the last,

Shut thee from heaven with a dome

more vast,

Till thou at length art free,

Leaving thine outgrown shell by life’s

unresting sea!

—Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Chambered Nautilus”

For we Americans believe in marriage and embrace it eagerly, over and over again. We bemoan our high divorce rate, higher in Dallas than anywhere else in the country. We pay lip service to the ideal of marriage for life, till death do us part. But in reality, if half of us divorce, four out of five of those who divorce remarry within five years, for the second, third or fourth time. One-third of all American marriages are remarriages.

And why not? As a nation we have historically prized starting over, wandering off — gone to Texas; California, here I come — in pursuit of happiness. Of course, strictly speaking, as my mother has pointed out, divorce and remarriage are not part of the Judeo-Christian tradition. But then, as William Faulkner once said, “The trouble with Christianity is that we haven’t tried it yet.” With the frontier gone, what easier, better, more American way to start over than in the dream landscape of a new marriage? Gone to Richard. Marianna, here I come.

After all, the next marriage might turn out to be the right one, the one we knew was possible all along, full of the simultaneous fireworks and serenity the pursuit of happiness promises us. “Yes,” breathed one divorced friend when I told her about Trey, “that’s one reason I haven’t remarried. Suppose I did, and then I found someone better?”

You pays your money and you takes your chance. Granted, it’s a heady thing, this marriage mania, but I can’t disapprove of it, even in my admittedly moralistic bones. “The man who hasn’t been married four times,” a well-known and often-married American writer joked recently, “is afraid of life.” So help me, I see what he means.

Sometimes I wonder why we insist on marriage, the thing itself. Surely, one would think, that by the fourth go-round anyway, two grown-up people could simply start living together, could create a “relationship.”

Many do. But with a curious blend of idealism and tenacity, we far more often insist on the real thing, the sacrament of marriage. For even, maybe especially, in our hedonistic age, marriage retains its mysterious power, its symbolic significance.

First marriages are touching, sure, statements of faith in human connections. But the couple, usually young, marrying for the first time is about as conscious of what’s happening to them as two blind puppies playing happily in their sack on the way to be dumped into the river. He jests at scars that never felt a wound. It’s the old veteran, limping courageously to the altar yet again, who stirs my admiration.

We marry for various reasons. I know one couple, already living together, that married in order to get a house loan. We marry to please department stores, the IRS, our life insurance company, the network of computers all over the country. We marry because our children need a mother or a father, because we’re afraid to be alone at night, because we want to pool our resources. Some of these reasons are good, others are not so good. The best reason to remarry is to please oneself.

Why marriage? Because, as John Leonard writes, relationships are to marriage what chewing gum is to nutrition.

Let’s assume the best, which I was lucky enough to get: We fall in love, for the second (or third or fourth) time in the real old-fashioned sense. The words of all those songs come true. Drink to me only with thine eyes. You walk in and the song begins. You’re the cream in my coffee. Bess, you is my woman now.

Once again we experience the miracle. In gratitude and hope, we marry.

Often afterward another miracle is required.

Here comes the bride,

God bless her hide.

See how she wobbles

From side to side.

—Folk parody, to be sung by derisive juvenile voices to The Wedding March

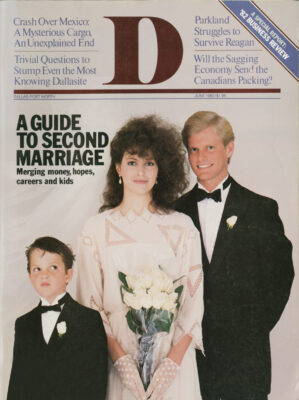

Second brides are wobbly brides. First time down the aisle, one’s responsibilities are simple. Veil on straight, say “I do,” kiss the groom, glow beautifully, throw the bouquet, live happily ever after.

The second time it’s not so easy. Things to consider include the children, the children’s father, the groom’s children and their mother, two sets of confused parents, various assorted grandparents and numbers of partisan friends. No wonder the bride wobbles.

According to The Bride’s Book of Etiquette:

Traditionally, a second-time bride avoids a very formal ceremony in favor of a semi formal or informal wedding for close friends and family only. But if you missed a big wedding the first time or want very much to walk down the aisle in a long white dress escorted by someone close, you may. Just be sure to share your plans with your parents so they can tactfully inform the rest of your family. That way your most conservative guests won’t be surprised on your wedding day.

Willem Brans and I were married on May 18, 1974. Our marriage was as traditional as a second wedding can be. I took his name, we exchanged rings, we used the time-honored vows. Often the accumulated beliefs and desires of maturity are more clearly represented in the ceremony than they were in ours. One couple we know, for example, insisted on being married at exactly 4:28 p.m. on a certain day, an auspicious moment selected by the bride’s astrologer.

We second brides aren’t given away; even the thought suggests to the cynical that we’ve already been returned once, as some of the wedding gifts undoubtedly will be. Instead we agree to share our lives.

For the groom, getting to the church on time may mean picking up the children first and trying to soothe their mother, who’s not too keen to have them go.

For our wedding, Willem’s friend Pat played The Wedding March from Lohengrin as I came down the hallway to stand by Willem under the arch of flowers in his family’s den. I was wearing a long pink organza dress with white polka dots, and was carrying a bouquet of wildflowers. My brother’s wife, Susan, attended me, and my new mother-in-law had arranged the simple home wedding; Elly and John have no daughters, and she wanted to do it.

My parents had come from Mississippi for the occasion, our friends were there, and looking around at them I beamed as I saw how moved they all were during the service. My children — Erin, 13, and Win-ton, 10 — had eyes as round as the polka dots in my dress, and my mother was wiping happy tears away with a sodden handkerchief.

Only later did I learn, from Erin, that Mother’s tears were not happy ones. “Mommy, Grandmamma cried and cried before the wedding, too,” she told me. “She kept saying, ‘It’s just so soon, so soon. I think Jo’s rushing into this.’ Granddaddy said so, too. And when Daddy came to pick me and Winton up after you left for your honeymoon, she told him the same thing. I think Grandmamma is worried about you, Mommy.”

I’m sure she was. Now my parents think Willem is great, but then they had their doubts, not so much about him as about me. In part it was my fault. I’d not told them anything much of the four years of trouble in my first marriage, and the divorce hit them hard.

My mother is the best woman who ever lived, but underneath her genuine Southern sweetness lies a hard Calvinist rigor regarding conduct. Marriage is for life, a woman’s duty is to her husband and children, and whatever is not a duty is a sin.

To such a woman, no matter how loving, the sin of divorce is mortal, and I had committed it. I should have had at least the decency to live like a spinster missionary until such time as an older widower, preferably a minister, noticed my decorous ways and stalwart faith. When this second marriage to a tremendously attractive young man followed on the heels of my first, she despaired of my soul.

Bravely, Mother kissed me, holding me to her wet cheek. She even drank a glass of unholy champagne. In a kind of delirium, I wasn’t conscious of her pain or how desperately my little boy clutched my knees when he kissed the bride or how thoughtful my gangly daughter looked.

If I had it all to do over again (how many times have I said that in my life?), I’d level with my mother from the beginning, tell my dreaming daughter how much in love I was, make my son more a part of the event. At least the children were there, dressed out in new clothes. “Don’t let them be anywhere else,” John Leonard writes.

A son shouldn’t go to the movies while his father is being married. If they stand around variously impersonating book-ends, alarm clocks, ghosts, sentries, tourists or refugees, give them a poem to read or some flowers to hold. They are important witnesses. It isn’t necessary that they altogether understand you; it is necessary that they take you seriously.

Since, however, I have seen children more significantly there than my children were at my wedding — bringing around a guest book to sign, demurely serving punch, taking photographs. I have heard them refer to “our wedding.” I once heard one little boy, whose father has been married several times, complain, “Why did I have to wear this old suit for Dad’s wedding? Last time I just wore shorts!” I remember a little girl with long dark hair walking down the aisle of a chapel with her hand on the neck of her companion, an enormous St. Bernard belonging to her new stepmother. Now that’s being there.

In the meantime I had to face the music, and it wasn’t Lohengrin.

The raison d’etre for the honeymoon today is fundamentally similar to its ancient purpose — to provide a transition between one’s past and future lives, a smooth path from leaving the childnest to become one’s own adult. Then, too, it is a means of prolonging the delirious high that surrounds the wedding festivities, a way of staving off the mundane realities of married day-to-dayness. —Marcia Seligson, The Eternal Bliss Machine

Maybe the troubles came because we insisted on a honeymoon; not every rewed-ded pair does. One couple I know loaded his two daughters and her son into a camper and set out for two weeks at Padre Island. Another pair tied the knot in their newly purchased family home, had a big reception complete with a string quartet and both sets of children, and went to bed as a large family, already settled in.

Willem and I slipped away to a quiet motel in Athens — Texas, not Greece — in the heart of the piney woods. The trip was a disaster. The first day we took a long walk through the thicket and came back to sit by the pool in the sun. When we went inside to shower for dinner, I was a funny mottled pink color all over and I burned with fever. Thinking I’d had too much sun, I rubbed myself with lotion and we went down to eat and try to be romantic.

The next morning the curious mottled rash was worse and my temperature had gone up. I took aspirin and decided to ignore it. Suddenly after lunch, one after the other, all my joints began to ache and then to swell — ankles, knees, elbows, knuckles. Whatever it was ricocheted around my body like a demon, hitting out at point after point.

Willem, alarmed, wanted to take me to an Athens hospital. “No,” I said, irritable with frustration and pain, “let’s just go home.”

All my upbringing came down on me. I was convinced that I was being punished for my sins and was feeling a tremendous guilt for having enticed this marvelous man, who’d never been married, had no children, no ex-spouse, no disturbed parents, no past, into the rat’s nest of my life.

So we drove back to Dallas three days early. My doctor diagnosed my ailment as a virus brought on by low resistance and high tension, and Willem and I took up married life.

Second marriages are the triumph of hope over experience. —Samuel Johnson

Dr. Johnson’s cynicism bothers me. I’d like to believe that they are the triumph of hope and experience, and that marriages are in fact a little like pancakes: If the first one turns out lumpy or thin, throw it in the garbage and start again. Surely we couldn’t make the same mistake twice. Or could we?

We certainly could. The divorce rate is higher and divorces come faster in remarriages than in first marriages. First marriages that end usually last at least seven years, remarriages three or less. Yet that’s not such a grim statistic for remarriages as it may appear to be. Remarriages simply have more danger areas immediately after the ceremony. Let’s look at the intrepid pair.

He has friends: Marge and Allen and Sue and Bob had him to dinner during his divorce trauma, introduced him to women later. She has friends: Alfred who takes her to the opera, Jim and Joanne who held her hand while her youngest had an emergency appendectomy, Lynn who saw her through the singles jitters.

Fact: These friends will not like the new spouse or each other.

Often the closer the friend, the more skepticism expressed about the marriage. Much of the disapproving world may be dismissed, of course. Willem calmed my fears about what people might say. “Let them talk,” he said, laughing. “It’ll be fun for them. But don’t you know, Jo, that really nobody cares? All those people out there don’t actually give a damn what we do. Nobody cares but us.” Well taken.

But some people do care, do worry about the marriage for selfless or selfish reasons. I’ve always thought this letter of capitulation from Willem’s friend Pat stated those natural concerns with an admirable honesty and kindness.

Dearest Jo,

Your call today was more welcome than you know, for I have wanted to tell you how happy I am for you both. Naturally I have wanted to withdraw my earlier disapproval of marriage plans. I did not know you then, but having gotten a load of some of the winners W. had picked out among women I had become inclined to distrust his good judgment in that regard. Truly, then, and with all my heart I can say that I think you are the best thing that ever happened to him, and I hope he in some fraction realizes his great good fortune in having found you.

So now, speaking of my state of mind since the end of last year, I look at Willem and say, “Christ, you’re a grown man; why aren’t you married or something?”

Love,

Pat

How could such a person but become a friend of us both?

If each newlywed has a coterie of loyal friends who might not meld, consider also the perils of employment. He has a job and she had a job. While Beth (or Jack) at 25 might cheerfully leave an entry level position at Modest Enterprises to follow a new mate to Dubuque, Elizabeth (or John) at 35, with rising status in Impressive Inc., is not about to do the same thing, still less at 45 as vice president of Controlling Corp.

Conflicting careers weren’t a problem for Willem and me when we married, though someday they might be. Money worries were. So were my children.

Willem had no nieces or nephews and had hardly been around children except in very structured situations. I remember coming back from that disastrous honeymoon, how eagerly and naively he looked forward to the joys of family life. Ha.

There are two kinds of travel: first-class and travel with children. —Robert Benchley

The joys of family life that first summer were similar to the joys of the honeymoon. We were both teaching then, and, jobless until school started, had to borrow money to live on until the first checks at the end of August. The four of us had moved into a big house on Rankin in University Park because I’d concluded that we needed space between Willem and the kids. The house was shabby and tasteless; the rent was high.

Even worse, the kids and their friends ran in and out of the central air, came from the pool tracking chlorine to take constant showers in their upstairs bath, and after a summer of their water games, the old bathtub upstairs began unmistakably settling down through the dining room ceiling; we could see its watery outline as we sat at dinner. Some evening I expected to have it crash through as a main course.

Poor Willem, so bookish and musical, with his Greek dictionary and his journals and his piano and his flute. He often looked like a bull that had been stabbed through the heart by the matador but hadn’t yet fallen down.

Then we discovered I had a nasty skin cancer on one shoulder and needed surgery. When I came out of the anesthesia, Willem told me what had happened. The operation had gone on much longer than we’d expected. At one point, my Egyptian surgeon came out shaking his head gravely, and said —

“Either melanoma or carcinoma, I couldn’t tell. I panicked,” said Willem. “I could hardly listen.”

Groggily I patted his hand.

“No, don’t get me wrong,” he went on dramatically, in mock despair. “All I could think was that if you died, I’d be left with no money, a bathtub in the dining room and those two kids for life!”

The honeymoon, such as it was, was over.

For, more than friends, careers or money, other people’s children make remarriage difficult. If I may offer a word of advice to those eager to become retreads, don’t try or expect to re-create a nuclear family in this remarriage. You had your chance at that and blew it. Your child, unless he’s very young, doesn’t need a new father; he has a father. The most your children can hope for is another friendly adult living in the house.

Recognize that you have, by marrying, brought into being a new kind of extended family, a group of households linked by children. There are no rules for treating these “family” members: How should your new wife behave toward your child’s mother, after all that you’ve told her? What etiquette applies to your ex-in-laws, your child’s grandparents?

No etiquette — just common sense and common humanity. In remarriage, by living together you learn how — or if — you love each other. Not all children are lovable, nor all adults, and these new family members are strangers to each other. Trying to impose preconceived ideas about togetherness gleaned from Eight Is Enough will only make liars of you all.

Anticipating problems might help: setting up arrangements about money, visitation, custody. But not all problems can be predicted. How can you know that your 5-year-old will suddenly start wetting the bed, as happened in one family I know? Or that you’ll call your new spouse by your old spouse’s name, especially during arguments? How can you prevent your child from saying, “You’re not my mother; you can’t make me”? You can’t.

If, as Freud said, two sets of parents are in bed with bride and groom in a first marriage, a remarriage is a Cecil B. DeMille crowd scene.

Dear Mom,

I miss you very much! The first night you were gone we had slightly burned cutlets, uncooked rice, and boiled parsley? He [Willem] thought it was greens and boiled it!

I saw the puppy from the Branses they said they are going to show him, but, they don’t want to see Scofia suffer and are putting him to sleep. I love you very much! Write me a long letter and I’ll write you a longer one.

lovingly,

your sonp.s. I love you

The summer of ’75 we moved from the house on Rankin to the world’s tiniest three-bedroom on Caruth. This move took place while I was ostensibly in Austin for eight weeks attending a seminar at UT and Willem was keeping the children. I would leave class on Friday, run by my apartment and grab a few things, and drive to Dallas. After a weekend of packing or, later, unpacking boxes, Sunday night I’d hop in the car and beat it back to Austin. It’s no wonder I got three speeding tickets cruising through Waco.

In the meantime, Willem and the kids were getting to know each other without my constant surveillance. The Branses are dog people, so when Erin wanted a puppy Willem bought her one, a registered Sheltie, which in Erin’s passion to be total Mommy she would never allow to be housebroken. In addition to all the other strictures on his life, scrupulously neat Willem now had a dog that had decided that the proper place to poop was behind the dining-room table on the gold carpet. He and Erin went around and around on that one.

Panicky because of our lack of money early that summer, Willem began to sell encyclopedias door to door. So after cooking parsley or whatever (he still hasn’t lived that down), he followed “leads,” for which he had to pay 50 cents up to $10, all over Dallas. He showed the presentation material, which had cost about as much as the puppy, repulsed the advances of lonely women, then returned to his makeshift family sans me. Finally, his personal goal became simply to sell enough encyclopedias to get one for our family. But he never came close. We borrowed again.

Nevertheless, at the end of the summer before school started, the four of us took off for a week, first to visit my parents in Mississippi, then to drive on down to the coast and New Orleans for a couple of nights. After a year, we had our family honeymoon.

Mother and Daddy, hearing our stories of the summer, especially the “parsley” tale the kids regaled everybody with, viewed Willem with new respect. Clearly this man meant to do right by their strange daughter and, even more important, by their grandchildren. Mother in particular took Willem to her heart. The two would huddle conspiratorially at the kitchen table while she told him what a difficult child I’d been and he brought her up to date.

“Her grandmother always said, ‘If you can get Jo headed in the right direction, all hell won’t make her change her mind,’ ” I heard Mother tell him once.

“Stubborn as a mule, you mean,” Willem answered, and the two laughed knowingly.

Yes, he took up expressions like “stubborn as a mule.” In his mind he’d married into a family out of Faulkner, though he couldn’t quite decide if we were aristocratic Sartorises or white-trash Snopeses. But he loved the big old white house across the street from the Baptist church, the long lazy days reading in the porch swing, the unlocked doors and constant comings and goings of family and friends.

“You wouldn’t if you had to live here,” I told him darkly.

But he wasn’t convinced. Born in Rotterdam, come to Texas by way of Maryland, this exotic foreign product charmed my folks with his interest in Southern food, flora and fauna, family tales, everything authentically Mississippian. He especially longed to meet my legendary cousin Willie Joe, almost the only one of my generation who’d stayed put to take over his daddy’s cotton land in the Delta, and even accused me of making Willie Joe up.

After our stay in Olive Branch, we meandered on down to New Orleans. We got kicked out of a Dixieland place because the kids were too young. “But they’re with their parents!” Willem protested, uselessly. All afternoon and night we walked the streets, buying T-shirts, junk jewelry, souvenirs. Erin got herself up for the evening, Willem groaned, like a Bourbon Street hooker.

But we let her be, and she had the loveliest adventure of her young life. Late that night as the four of us came back into the Cornstalk Hotel where we were staying and started up the wide stairs to our rooms, a handsome and inebriated young man walked up to Erin, brought his hand out from behind his back and handed her a long-stemmed red rose. “I’ve been following you for blocks,” he said. “Honey, you’re the prettiest little thing I ever saw.” With Willem, Winton and me watching, he bent over and kissed her gently on the cheek. Then he straightened up, turned and marched away with dignity.

I looked over at Willem and smiled. He was visibly shaken. “And she’s just 14,” he moaned. “What have I done?”

If Willem took my Mississippi relatives to his heart that summer, I had already learned to care about Elly and John and Willem’s brothers, Jan and Jacobus, called Jay. They had brought me and the children into the family warmly. My new connections had a great sense of festivity and celebration — no teetotalers in this crowd.

The kids and I discovered holidays and customs we never knew existed. I’ll never forget the first December 5 that Elly and John showed up with presents that included giant chocolate initials for the names of all four of us — St. Nicholas Day. These gifts led to a lot of family feeling, as we sneaked bites of each other’s W or B. “You ate my E,” Erin accused Winton. He denied everything. Willem is the worst culprit. I know for a fact that for the last five years he’s finished off the loop of my J, if I could just catch him at it.

At Easter, homemade baskets composed of ladyfingers and chocolate appeared. At Christmas came the Dutch breads and pastries: kerstkrans with almond filling, olie bollen covered with sugar and kerstbrood with raisins and fruit. John had been a baker in Rotterdam during the war, and he had learned his craft well.

This family had stories too: of Willem’s Uncle Willem killed by the Nazis, of the war years when John was in hiding part of the time, of the big ship Groote Beer they sailed to America on in the postwar years.

The whole family had been naturalized on November 22, 1963. “We were in the courtroom when the news came over the loudspeaker about Kennedy, and we almost changed our minds.”

Sitting at their dinner table, Erin nudged Winton to see the rug on it under the white cloth and the Dutch plates. We drank endless glasses of wine, ate stimp stamp or aardappelen-sla-en-eieren and felt the world grow as small and cozy as the dining room.

Marriage, as I have said, is a form of action, of violence almost: an assertion of the will. Its orbit is not to be charted with precision, if misrepresentation and contrivance are to be avoided. Its facts can perhaps only be known by implication. It is a state from which all objectivity has been removed —Anthony Powell, At Lady Molly’s

Over the years, Willem and I have had our biggest battles where the children are concerned. Discussion: Willem says his theories of child rearing are from the ’50s and mine are from the ’60s. Hotly I answer: “What d’you mean, theories? I have no theories.” You see what I mean.

But I think our differences lie elsewhere, perhaps in our family or even our cultural backgrounds. We liked each other’s family, reveled in the differences between the two, but those very differences made trouble for us. The children were a ready-made battlefield.

My attitude toward my children is laissez faire: Trust them and worry a lot. His is disciplinary: Watch them, control them, don’t let anything go by. With his Old World expectations, Willem saw the children as malleable creatures, needing constant training. With my peculiar American and Southern romanticism, I saw them as pure beings, trailing clouds of glory, who only needed love.

We have fought this battle openly, even in the presence of the children and to their utter confusion. Bad, bad, very bad. The funny thing is that I often know he’s right, but my hackles still rise. The friend who introduced the two of us a decade ago exclaimed in horror when I told her we were getting married, “But, my dear, he can never handle your children!” — emphasis on “your.” She had a point.

On the other hand, he can handle our money, their schools and our cars and house and pets and lawn and all the rest of it — what Zorba the Greek called “the full catastrophe.” He can handle me, and according to my mother, that’s not easy.

And if, thinking over these things, I remember miserably the entire contents of a note from Winton I once found on my pillow: “I HAT Willem!,” I also recall Erin’s recently telling me about a new boyfriend: “You’ll like him, Mom. He’s great.” She grinned. “Isn’t it funny? He’s a lot like Willem.”

Freud works in mysterious ways his wonders to perform.

Hester assured them, too, of her firm belief that, at some brighter period, when the world should have grown ripe for it, in Heaven’s own time, a new truth would be revealed, in order to establish the whole relation between man and woman on a surer ground of mutual happiness. —Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter

Like Hester, I believe in remarriage. By the time you read this, Willem and I will have been married eight years, knock on wood again, and Trey is just a leap in my fancy on those occasions when I too “HAT Willem.”

Of course I hate him sometimes. Even Mrs. Ramsay, that paragon in To the Lighthouse patterned after Virginia Woolf’s mother, herself a second wife, looks down the dinner table at her husband and countless children and meditates, “But what have I done with my life?”

We spoke of miracles. The biggest miracle is those eight years, and the eight to come, I hope, and the eight after that. For in addition to the potential mine fields I have already mentioned in the dream landscape of remarriage, the characters of the partners themselves contribute to readier divorce. Those who remarry have of necessity gained some expertise in living alone. They change spark plugs, sew on buttons, read insurance policies, concoct a mean curry as the need arises. Less willing to accept the neat demarcations of duty in traditional marriage than they were, they are also less willing to tolerate unhappiness. They know they can make it separately, so it’s not a matter of life and death to make it together. The world will turn, the stars will shine in the night sky, the sun will come up on schedule even if they divorce, something mates in first marriages genuinely doubt as disaster hits.

Such independent souls will remarry, for love, for comfort, for companionship, but they can handle life alone. Robert Frost once said of the woman to whom he was married for a lifetime, “Elinor is of no earthly value to me.” Quite as it should be, in my opinion.

“Where were you born?”

“Out of wedlock.”

“Mighty pretty country around there.”

—Ring Lardner

Perhaps all marriages ought to occur, like one second wedding I attended, on the Feast of St. Thomas the Doubter. A little healthy mutual skepticism, a certain ironical cast of mind, never hurt any marriage worth having.

Certainly all marriages ought to be remarriages in a sense, even if the same two people remarry. As Frost implied, marriages are spiritual as well as physical dwellings. No growing human being will be the same at 25, 35 and 45. Growth and change are the laws of nature, and the soul may outgrow its habitat as the chambered nautilus outgrows its shell. Then something has to give — the dimensions of the spirit or the terms of the marriage. Far too often partners cut off their legs or move out.

But some marriages grow with the partners, stretch and extend, and they are wonderful to see. And I have a need for my legs. Remarriage belongs to pilgrims, to people who discover truth in process.

We may never reach the Celestial City, but we’ll see some mighty pretty country on the way.

Remarriage is not art. It’s better. It’s life.