THIS IS A STORY of families and honor and house guests and it takes place in the home of R.B. Caldwell, a cautious man who harbors one obsession.

Caldwell, 57, has been a stockbroker for more than 30 years. “Yeah, that’s what I do for my living,” he says. “That’s what I do. Sell stocks.” But Dow Jones Industrials are not what preoccupy him any time after five o’clock.

The obsession: Caldwell has put together one of the finest Japanese sword collections in the country during the past 25 years; he is well-regarded internationally for his knowledge of Japanese history and his writings on samurai swords. The swords he collects were once status symbols of ruling-class families. Today, Cald-well’s collection gains him entry into a select group of respected sword aficionados, people among whom he is proud to be counted. That privilege comes from having money to invest; the money comes from his wisdom in telling other people what stocks to buy. Caldwell is American gentry by birth, but by collecting Japanese swords he has filled his head and his household with signs and symbols of greatness. He says he doesn’t collect swords; the swords collect him.

“The collection began for investment purposes,” says Caldwell. “But I don’t believe anyone can build a fine collection if money is the first criterion. I’ve gotten to the point where it’s… ah, something more like a passion. Art is an investigation of sorts, and I’ve spent at least fifteen years of my life trying to understand the Japanese sword.”

In addition to being a sword connoisseur, Caldwell is almost solely responsible for bringing a gen-u-ine samuari sword-smith to Dallas every year. Caldwell and plastic surgeon Dr. Masashi Kawasaki saw to it that the first swords ever forged in the Western Hemisphere were made at the University of Dallas in 1980. Since that time, Caldwell has built his own Kajiba, a sacred gazebo-like shed, in his North Dallas backyard just beyond the patio hot tub that belongs to his son, who lives in the house next door. Yoshindo Yoshihara, one of the most accomplished young swordsmiths in the world and a man everyone assumes will become a Japanese “living treasure,” comes to visit the Caldwells every spring, and he makes his swords in Caldwell’s Kajiba in the ancient manner over a charcoal fire, the way it’s been done for thousands of years.

You know the James Thurber story about a unicorn in the garden; well, Caldwell has a similarly mystical visitor, only in this case it’s a swordsmith. The garden Kajiba is nicely situated between several low-lying trees. There’s a waterfall off to one side, and a statue of Buddha positioned beyond that. From this standpoint, it’s difficult to believe the state is still Texas.

Yoshihara, now 35, began to learn the swordsmith’s art from his grandfather when he was 10 years old. Some of the complicated procedures come to him as innately and easily as breathing. That is what fascinates Caldwell. The ability to forge swords is, in this case, a birthright as well as an accomplishment.

“When I watch Yoshihara work,” Caldwell says, “I find myself in absolute, total awe.”

When Yoshihara is in town, everything in the Caldwell household revolves around him. “This is where the swordsmith sleeps,” Caldwell proudly pronounced one evening last April. The swordsmith that night was, apparently, “out on the town.” And there, sure enough, in the indicated upstairs bedroom was an open suitcase and a pair of Japanese wooden thongs so neatly aligned beside the bed that it seemed admirable.

“He likes that gooey rice,” Mary Anne Caldwell remarked on the challenges of entertaining a Japanese house guest, “not the American kind. And he went out and bought a special bowl for it because I didn’t have the right size.”

Members of the Japanese Sword Society, who filter in from all over the country to watch Yoshihara work, pay for the swordsmith’s Tokyo-Dallas airfare. This year, American smiths from Arkansas, Oregon and Michigan came to see Yoshi-hara forge swords in Caldwell’s Kajiba. They were a scruffy bunch, as ironsmiths and cutlery makers are apt to be. One young man spent his days in the Kajiba and his nights at a local campsite, where he slept in a tepee. R.B. Caldwell schlepped around all week in old sport jackets or a favorite cardigan fastened by the center three buttons. On some of those days he neglected to shave or comb his hair. Watching Yoshihara fashion swords for 10 days each year is Caldwell’s vacation. Some of the most memorable times have been when Caldwell has donned the ha-kama (Japanese smithing garb) and forged some blades under Yoshihara’s direction.

Turning a substance that looks like a chunk of asphalt into a silvery, silken expanse of highly reflective blade takes some doing, and the forging process is truly something to see. There are three types of blades: the tachi (a long sword), the katana (of medium length) and the tanto (a dagger). All begin as irregular rocks of specially mined iron ore that are heated in the forge to a temperature of about 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit on a pine charcoal fire sustained and controlled by an animal-skin bellows. The iron is folded over and pounded flat, then reheated to a fiery red glow and folded flat again and again -at least 15 times. A softer core of metal is frequently forged into the center of the blade for greater flexibility and strength. Yoshihara spends days elongating the lump of ore into a blade until it has a nice shape worth tempering in a clay covering of various thicknesses – thin along the cutting edge, thick on the back. After the blade is reheated and quenched in a long trough of water, the swordsmith examines the blade closely for imperfections and impurities. It is then determined whether or not the blade is worth taking back to Japan for an equally laborious process of polishing.

Yoshihara has decorated Caldwell’s backyard Kajiba with ceremonial lanterns and paper cuttings for good luck. The American smiths help Yoshihara by burning fresh hay outside the shed to make special purifying ashes. The iron is rubbed into the ash between bouts in an asbestos-lined charcoal pit. The forge is always filled with sparks of flying iron scales and the hissing sounds of hot air and steam. To R.B. Caldwell this is heaven. It is a place he probably correlates with a centered mind and peace.

It grieves Caldwell that many Americans can gaze at a completed Japanese sword and remain relatively unmoved. Even his wife admits that the swords don’t do much for her; she prefers the ornate casings, knowing full-well they’re poo-pooed by serious collectors as purely decorative.

“Some of the casings or scabbards are beautiful,” Caldwell says. “And some of them are quite good. But the sword is the real issue. The blade is the thing.”

Caldwell tried to get the general public involved in Yoshihara’s most recent visit by organizing a two-day sword show at Hartman Rare Art in the Fairmont Hotel. Ads were placed in weekend newspaper supplements; a postcard was dispatched to those known to be interested. The smiths from the Kajiba showed up, as did some university professors, a local acupuncturist and some students of the martial arts. But no buyers.

“We have so many other things that draw larger audiences,” said Mozelle Abbott, who runs the gallery. “Sword collecting is a comparatively minute field. It’s not something the general public gets very interested in. I suppose it takes a special sort of mind.”

The people who did materialize for the opening seemed to be having an excellent time; they drank wine and conversed gregariously.

“The Japanese have such respect for swords like these that they don’t talk at sword shows,” said an American smith who seemed to be disapproving of the festivities. “They don’t even breathe too deeply near a sword for fear some moisture will fall on the blade and cause it to rust.”

“The Japanese sword is the spirit of the maker,” said Dr. Kawasaki when a sword-making squad was working at UD. “The samurai who wore it revered it as his soul. Together they represented the tone of Japan. In periods of peace, the sword maintained its revered position and was relegated to the province of art.”

Caldwell calls the swords the “finest expressions of Japanese civilization.” There’s something about the weight of the weaponry, the gracious contours of the shiny steel and the razor-sharp edge of each sword that all work to mesmerize him. When he gazes into the face of a blade (whose mirror-sheen is no different than that of the chrome pillars at One Dallas Centre where Caldwell has an office), he sees perfection -something he has otherwise been unable to obtain. Perfection-in the sense of predictability -is something he’s never gotten from selling stocks. With swords, one can gauge quality; there is a standard. There is a value that is real.

Caldwell begrudgingly admits that he leads a bit of a double life. He abandons work to take sword-buying trips to Japan once or twice a year, and he takes time off from the office when Yoshihara comes to Dallas. Someday, perhaps when the sword market is more supportive and the general public is more knowledgeable, R.B. Caldwell might become a full-time Japanese art dealer or critic. But that will take money he implies he doesn’t have. And courage.

Caldwell is not a risk taker. He’s a modest man who doesn’t care to attract attention to himself or his collection, at least not now. He doesn’t like to say how much his swords are worth. They are worth a lot. Yoshihara’s long tachi swords sell for $6,000 to $8,000 brand-new. Antiques go for whatever the market dictates, depending upon their quality, of course, and their condition. Caldwell maintains a steady assortment of 50 blades in a bank vault. If he buys a new one, he resells another. His oldest sword dates from the 12th century.

“R.B.’s always been a compulsive buyer,” his wife says, “whether it’s samuari swords or Tabasco sauce.” But she’s glad her husband has sustained the collection. She thoroughly enjoys the trips to Japan and the two of them have, she says, met some “really wonderful” people through the sword society, people such as Walter A. Compton, chairman and chief executive officer of Miles Laboratories and probably the only collector in the country whose sword collection is more prestigious than R.B. Caldwell’s.

Caldwell says his father, who was an attorney, would not have approved of his interest in art swords. “I don’t think he saw art as something a man would get involved in,” he says. But Caldwell imposes no such outdated dogma on his own sons, both of whom are musicians in a punk rock band.

There are a lot of crazy twists to the Caldwell household, from the kids’ careers to the furnishings. Their son Neal owns a hip record shop on Cedar Springs. In the glassed-in back porch, an imposing Narwhal whale tusk extends from a table toward the ceiling. Two very disobedient dogs are always underfoot, and they contribute to the general confusion of the place during Yoshihara’s stay. Caldwell’s sons are occasionally around, flipping beer tabs and preparing to practice with the band.

Caldwell presides over the household when his wife is out playing tennis or in Fort Worth on a museum jaunt. And he seems non-plussed by all the activity. Members of the sword society hang around the house exchanging sword stories in soft whispers. They speak of polishing techniques, anvils or other tools and famous battles fought by the Japanese.

R.B. Caldwell stands out amid all this. He is an honorable man, a wealthy man, an offbeat man, a man who has only recently realized who he is. Ten years ago Caldwell wrote an essay on swords in which he posed the question: “What does this blade mean in terms of people; who were the men who lived to make this sword and died because of it?”

He was wondering that before he began to take in Yoshihara every year as a house guest. That was before he came to admire, to almost idolize, Yoshihara for being a simple man destined to do only one thing well. Eight years later Caldwell built the Kajiba in the backyard and dedicated it to the memory of Bill Trevino, a practicing sword polisher from Denton who had helped build the Kajiba and had died just before it was fired up for the first time. “Bill was a wonderful, relaxed guy,” Cald-well says, “who just fell in love with the Japanese sword.”

In another passage of the same 10-year-old essay, Caldwell quotes the poet Basho: “Of the Warrior’s dreams, nothing remains but the summer’s grasses.”

“One wishes Basho could have added: ’And his Sword,’ ” Caldwell wrote.

But the poet didn’t say “and his sword.”Nothing remains but the summer’sgrasses. Caldwell has by now worked allthat out. In learning to understand theproperties of the Japanese sword, he hascome to better understand himself. Youcan see that knowledge in his face whenhe’s sitting in the Kajiba staring deep intothe fire.

Get our weekly recap

Brings new meaning to the phrase Sunday Funday. No spam, ever.

Related Articles

Local News

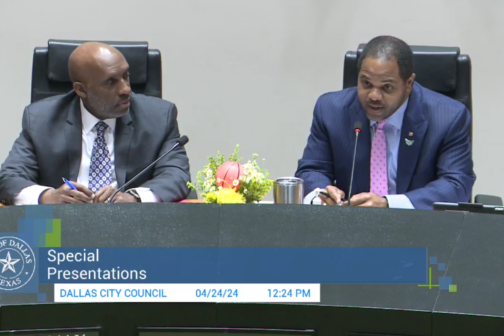

Mayor Eric Johnson’s Revisionist History

In February, several of the Mayor's colleagues cited the fractured relationship between Broadnax and Johnson as a reason for asking the city Manager to resign. The mayor says those relationship troubles were "overblown" by the media.

Media

Will Evans Is Now Legit

The founder of Deep Vellum gets his flowers in the New York Times. But can I quibble?

By Tim Rogers

Restaurant Reviews

You Need to Try the Sunday Brunch at Petra and the Beast

Expect savory buns, super-tender fried chicken, slabs of smoked pork, and light cocktails at the acclaimed restaurant’s new Sunday brunch service.