So you thought you were ready for anything, all switched over to survival mode, waiting out the deluge with grim-humored Eighties macho, shockproof and impervious to burglars, muggers, child abusers, heavy users, wheelers, dealers and all the other life liberty and the pursuit of happiness threateners that fall from the sky and wait in the weeds? Looked over every enemy-foreign and domestic, real or imagined-and talked through every Disturbing Trend and Major Development until you’re jaded by them all? Well, here’s news. Take another sip and brace yourself.

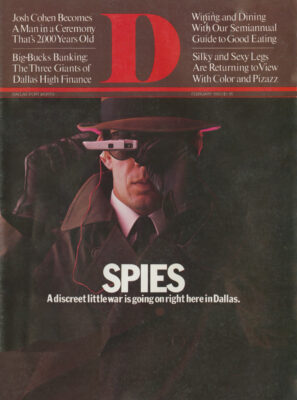

There’s espionage. That’s right, you heard it. Spying. Right here in Dallas, there’s this very discreet little war that pits honest-to-God spooks, as self-effacing and anonymous as George Smiley, loaded with state-of-the-art paraphernalia that puts James Bond’s trinkets in the same pile with Iron Age artifacts. And we’re not talking about your mundane foreign intrigue here, although that probably goes on-that Cold War clash of FBI/KGB/CIA civil servants filling in their forms and shipping off their microdots and waiting out retirement. We’re talking about your high-gain stuff, played out daily for stakes running into the millions, pervading the marketplace so thoroughly that it threatens to suck in all of us-programmers, lawyers, layout artists, construction workers, even writers, all of us-before it peaks out and is accepted into the mainstream of our economic life. If it hasn’t already. What we have here is industrial espionage, a problem that is rapidly becoming a crisis.

In Dallas! Does that surprise you? It shouldn’t. If you make your living peddling hot information, Dallas is a veritable mother lode. Research and development in industry leaders such as TI, E-Systems, LTV, all turn out highly valued know-how as a daily chore. Raw data passed and held by firms ranging from RepublicBank to Blue Cross to Chilton Corp. could be put to a mind-boggling combination of uses. And who makes a profit on information? Right, enter the spook, and a whole industry conducted in whispers and shadows, creating a market for bizarre tools – night-scopes, phone scramblers, acoustic-wave generators -and a bonanza in jobs for investigators, hostage negotiators, microcir-cuit engineers and an entire host of trades.

You don’t have to look very hard to find all this out. Just take a look in your Yellow Pages under “security” or “detectives.” Arcane names, inspired euphemisms: Magnum Force, Total Assets Protection, Sole Source Security, Absolute Security and Investigation, Ace Detective Agency, Fidelifacts, Quattlebaum Investigator and Security. Check the directory from 10 years back and you’ll find small ads for domestic cases and catching thieves on the loading docks. Check a current directory and you find big ads for “information for business decisions,” “personalized bodyguards,” “detection of telephone tappings,” “motion and still pictures,” “undercover agents,” “executive protection.” Some promise to verify your suspicions. Some give you access to a European agent net. One even advertises “document destruction” from billboards on the freeway. You can choose from any of a dozen or so nationwide security giants -Wackenhut, Burns, Rollins, Pinkerton -that have Dallas garrisons, or 60-odd homegrown firms formed up of ex-cops, former FBI agents, retired military-intelligence types, National Security Agency-trained communications specialists, and on and on and on. Those people are there to guard against more than simple breaking and entering.

Ask them. “Just about every practitioner deals with protection of information,” says Lou Tyska, national president of the American Society of Industrial Security, AS-IS to insiders. Tyska, incidentally, heads security for Revlon, a cosmetics firm operating in an industry where losses to pilferage are considerable, but a loss of trade secrets can shut you down cold and dark. This is not news: It’s been going on for decades, and we all know it. How much of it goes on lately, and how far it gets carried, this is what the AS-IS chief describes as a “real horror show.”

What you find after talking to these people for any time at all -and security types are not given to loose talk -is that industrial espionage comes close to touching anyone who works and thus has access to business information. So if you’re charmed and beguiled by the appeal that secret games make to the adolescent in all of us; if you’re into betrayal, fraud and corruption; if you’re blind to the risks and costs, then your best course is to plunge right in. If, on the other hand, you like to know who’s listening and where it’s going; if you want to keep up with who you’re working for; if you have a strong distaste for being used, then there’s a way for you to stay out of it. If you know what to look for and how to recognize what you’re seeing. In either case, you have to learn -intimately -the same motives and methods, techniques and tradecraft, resources and reflexes. Avoiding espionage -from Checkpoint Charlie to Market Hall -demands the same talents as doing it. This is your first briefing. Listen up.

The first thing you have to learn – really get comfortable with -is that you’ll never see the whole picture, just pieces. Nobody ever sees the whole picture, not even the people who do this full time. Especially not them. Compartmentalization and need to know are the first buzzwords you hear in the security trade. You build a dim framework, divine by intuition what each fragment is likely to mean in light of whatever else you know. You must keep it simple, if you’re serious about it, and avoid the impulse to play Dungeons and Dragons, to break the code, to unravel the web. Here we’re playing for keeps: Discover the obvious threats first, set loud alarms around them, then proceed to the next layer. Protect your space, keep your perimeter tight and constantly ask yourself: What does it all mean? Paranoia helps enormously.

What brought all this on? Well, it seems that industrial espionage, and guarding against it, are the chief growth industries of the survival-oriented Eighties. Trendsetters-admen and rock stars, for example-are telling us that life on Earth is not meant to be lived so much as survived, and survival means eating snakes and cutting throats. Against this Dark Ages ethic, the native American drive for success boils down to this: There’s still plenty of money to be made if you just get there first and rip off your chunk.

That’s anywhere. AS-IS claims 16,000 “practitioners” in the United States, another 2,000 overseas. Tyska says security against all sorts of pilferage and plunder has grown into a “multibillion-dollar industry,” with huge conglomerates buying out security hardware and service firms, giving themselves a protective arm. “The bigger the company,” Tyska says, “the bigger the risk.”

There’s a piece of the puzzle you can get at with a couple of phone calls. Businesses make money on the best bets, and they’re betting lots of it on security, setting hard, deep defenses against all sorts of piracy. Why the upsurge? “It may be due to inflation,” Tyska speculates. “Inflation leads to barter, and people tend to sell what’s closest to them.”

It’d be nearly impossible to estimate how many free-lance spooks are out there. The businesses that hire them don’t want to talk about it, obviously, and the spooks themselves don’t advertise. The size of the force that’s securing against them – enough in Dallas to form a world-class intelligence agency -tells you more about how much damage any one spook could do than about how many spies are skulking around the market. There are a few indicators, though. The Defense Department’s security agency – Defense Investigative Service -has recently opened a separate office to deal with protecting classified information used and generated by government contractors. And they let you know right out front that they’re not getting mired down in corporate spying.

“Industrial espionage is a management problem unless, of course, classified information is involved,” the DIS says in its pamphlet for contractors, right after they tell you who they are, and before they define “classified information.” The FBI can’t get into industrial espionage cases without a criminal complaint -which violated victims are loath to lodge -though it does offer free advice. So that leaves you.

You’d better start by locating the spooks first. If they’re in it for profit, then follow Deep Throat’s whispered advice and “watch the money.” Any company that has a competitor has money to lose, and therefore secrets to keep. If that describes your employer, then you need to start looking close-by. The spook is going for the information, which passes through a company like nourishment through a digestive tract. It enters as policy, formed in the board room, converted to paper by word processors, transmitted by mail and telephone, resting on desks and workbenches until the task is under way, then finally ejected as trash out on the loading dock and into the Dumpster. You can tap into that flow anywhere along the path, using different tools at different points. If you want it on cassette, bug the board room or secretaries’ phones. If you want it on floppy disk, buy off some underpaid typist. If you want it sorted and franked, stroke an ambitious mail clerk. If you want it by the ton, lease a truck and underbid the trash contract.

You can see all this happening, but only with specially trained eyes, vision focused on the part of the spectrum that doesn’t show. Walking to your car on any given downtown night, you can see single floors lighting up in the tall buildings as custodians move up, cleaning for the next day. You might see one office on one floor shining above the others. What you don’t see is the janitor in the new crepe-soled boots peeling off from the others, walking perhaps a little too straight and brisk for a graveyard-shift cleanup man. He steps out of the elevator moments after the guard passes, sticks a pistol-grip lock pick into a door, and slips in, locking and wedging the door behind him. Working in well-rehearsed moves, he puts on surgical gloves and begins pulling out files and photographing them. When it’s time to go, he stops at the executive secretary’s desk, almost as an afterthought, takes the film ribbon out of the Selectric and puts in a new one. He’ll read the used tape at his leisure, but you won’t see him do that, either.

Or maybe on the way to pay your rent, you notice a phone company truck parked at the terminal box at the end of the building, with two men fiddling with wires. What you don’t notice is that the logo on the truck is cut from stick-on shelf paper and that the truck doesn’t have nearly as many tools in it as others you’ve seen, or that when they close up and drive off, they leave a short, fat wire in the terminal box clinging to one line like a leech.

Or maybe one night at some Greenville Avenue club, you idly watch an out-of-towner -a real hayseed in a leisure suit, his hair parted low on one side and combed up over his bald spot. And you marvel at how easily he scores with the little silver-haired fox at the end of the bar, and smile at the slightly astonished look on his face as they leave. Later, alone at his home in Borger or San Angelo or Tyler, he gets a phone call, a 30-second tape of moans and sighs, and himself gasping and wheezing silly little nothings in a very high state of arousal. Then the caller assures him that no one else need ever hear this thing, if he’d like to cooperate, say, in talking about some areas where his company is interested in drilling….

If you’ve spent any time in the cold, as they say, then it’s second nature to watch for all this. You can recognize the spook, whether he’s on someone’s payroll -on your side, as it were -or whether he’s working in shadows, by the methods he uses, methods worked out through centuries by trial and error, passed on from master to novice like gypsy lore, simplified with technology but basically unchanging.

Here’s how it works. You know XYZ Corp. has saturated the market. Digital watches, say. You learned that by reading their annual report, which you got by buying a couple of shares of their stock and getting on the mailing list. You know the company’s branching out into something else, and because your tipsters told you – or you heard a rumor at the club, or something-that they’re making inquiries into buying a company that makes, say, small speakers, you have a pretty good idea XYZ is getting into something that talks.

Now all you have to do is hire away one of XYZ’s salesmen and you know where they intend to sell it; watch their loading docks and you know how much; buy a copy of the feasibility study and you know how much is left for you; corrupt one of their subcontractors and you’ve got the designs, and so on. That’s basically what happens, vastly simplified, with thousands of variations.

And just as the mainline dynamics of an intelligence operation follow a well-established thrust, so do the everyday mechanics of each encounter: Spot a source, check him out, move him into your space and take control; find out how much he knows and what he wants for it, do the deal, cut him loose. Some assumptions are standard: Everybody’s using everybody else; nothing is what it seems; everybody in it is playing some kind of game. So there are fixed rules about recognition signals, fallbacks, cover stories, safe houses, security-always security, everywhere security – all the things you learned reading Le-Carre. It’s just a little eerie to see them in natural, comfortable use right here in your hometown. But no one’s immune: From your first Baden-Powell stalking game, there has been this fascination with stealth and deception. Your real desire, deep down in your soul, is to see it happening. Keep that in mind on your first contact. Which can start as easily with the Yellow Pages as with anything else.

A call to Starken Corp. leads you to security consultant Dan Cofall and a 10-year flashback to your own bush-league flirtation with espionage, as a wartime Army Intelligence agent.

You meet in Cafe Pacific, his choice. You’re sitting at the bar drinking a Coke – no martinis, shaken not stirred, and you imagine you’re living by your wits -when he comes in, looks around for a tall guy with a red beard, his recognition signal.

“Are you the one I’m supposed to meet?” he asks.

You nod, handing him a press pass. Your bona fides, it’s called.

“The beard’s new,” he says, looking from face to photograph.

“No. The picture’s old.”

It turns out that Cafe Pacific has stopped serving lunch, so you get into Cofall’s car and drive to another place of his choosing, a deli in Preston Center. It’s empty when you arrive. You already know how it feels to sit on his side of the table: Anyone in this business-however peripherally-lives in terror of being fooled, so for an hour you talk about being a reporter, giving the source time to check you out. And when he’s comfortable, Cofall stops asking questions and starts answering them.

“Well, to begin with, industrial espionage is a terrible misnomer,” he says. “You think of little men in black suits breaking in and rifling the files. The security department in most companies is there to check the drawers. We try to stress that the problem isn’t physical security, it’s people.”

That’s where you come in. Oh, you can find out what’s going on in a company by keeping track of comings and goings – which salesmen are calling, what shows the buyers are going to; or you can plant an undercover agent, a mole, inside the firm -tedious, needlessly expensive, excessively melodramatic. “But the easiest way is just to hire someone away,” Co-fall says.

Of course. Keep it simple. And legal. But how?

“Call up a management recruiter,” says Cofall. “You can order just an accountant, or you can order an accountant from XYZ Corporation.”

Ah! So that’s what was happening, that week you got all those calls from a half-dozen headhunters, all asking for you by name. Kind of gave you the big head, didn’t it? Of course it did. Flattery is a key element of seduction all over the world. Case officers spend it like change. There’s no limit to what you can get for it. Lure someone with a new title and a foxy secretary, pump him for six months, cut him loose and hire someone from another competitor. That’s a good place to set a loud alarm, triggered whenever anyone is taking an inordinate interest in you. Especially if what you do is not particularly interesting. “Nothing passes more easily than information from engineer to engineer,” says Cofall. “They’re so eager to show what they’re working on. It’s their whole life.”

So what happens if you do hire over to the competition? If you just take your pay raise and your company Buick and spill your guts? Sometimes, nothing. If your new employer appreciates a hand who can’t be trusted to keep a confidence, then you’ve found a home. Best to keep a cushion, though, somewhere to land when the information runs out. In espionage, the clean information-commercial brochures, government records, news articles, scholarly and trade papers -comes from “white sources.” Snitches, defectors, turncoats all fall under gray sources, a little soiled, something the firm doesn’t really want to claim. And if none of these work?

Go to black sources. Break the law. If you’re unimaginative -like the Nixon Administration – or just too stupid and clumsy to figure it all out in the clear, you start bugging. Now, Cofall sells and services the equipment to sweep for bugs. An exterminator, it’s called: You can even work out a contract for an initial sweep followed by periodic visits, like the Orkin man.

“When I go in to pitch my service,” Co-fall says, “about one time in two 1 find a bug while I’m demonstrating the equipment. Sometimes it’s one the prospective client planted himself, just to see if the equipment really works. Sometimes it’s not.”

Well, that fact tells you two things: First, people do get bugged and don’t know it; second, “prospective clients” know where to get bugs themselves.

“Yeah, you can buy some of the stuff down at Radio Shack,” Cofall confirms. “For special jobs, you have them made to order here in town.”

“They’re not hard to find,” he says. “Mostly it’s pretty standard designs. You have to have a transmitter powerful enough to penetrate walls and travel at least from the floor it’s on to the street. And you have to have a power supply that’ll keep it running long enough to do any good. And you have to transmit on a frequency no one is likely to scan -almost everybody drops it in between the aircraft and FM bands. All that defines the parameters of what you can use.”

Cofall opens his briefcase and starts showing his line of hardware. There’s this little detector that fits in your coat pocket, with a pickup on your wrist. You use it to sweep an individual to see if he’s wired with a mike or recorder. If so, the little box vibrates excitedly against your chest. Was there an exaggerated slowness in the way Cofall raised his hand to shake, back there at Caf坢 Pacific? Was he just playing the game? Or are you? It’s not cool to ask.

How do you plant a bug? Keep it simple.

“The easiest way is just to walk in and hand it to the target,” Cofall says, pantomiming. ” ’Hey, I’m the new sales rep with XYZ calculators. Here, take this one and carry it for a month. Use it, see if you like it.’ Anyone will carry anything free for at least a week. If nothing else, it’s good for stories about how this schmuck just gave away a calculator. Or send his secretary flowers. No one thinks to dig up a pot of flowers.”

And if you have a sense of irony, you can artfully conceal it in a reproduction of the Trojan Horse, you suggest playfully, something to decorate his waiting room. “Yeah,” says Cofall with a smile. Later, he adds, “I can see you’re no virgin.”

“Then we have this,” he says, offering a small black scope with an odd green glow in the eyepiece. “It’s a pocket night-vision device. Passive: The target doesn’t know he’s being watched. It adapts to this.” He shows you a camera about the size of a pocket harmonica. “This is a Minox C. If you’re going to get a Minox, pay the extra money and get the C model. Far superior to the A and B models, worth the extra money, and it adapts to the Litton nightscope.”

How large a market is there for this stuff? Well, night-vision scopes are bread and butter for Varo Corp. in Garland, though most go to the military, in about 50-odd countries. And Litton’s Tempe, Arizona, plant makes enough of them that it’s worthwhile to advertise on pocket flashlights bearing the slogan: “Look to Litton for night vision.”

Cofall gives you one of these, as a gift upon parting. The whole interview leaves you a little unsettled. Not shaken, really. That won’t come until you’ve checked all this out, confirmed your darkest suspicions. Meanwhile there are other little things: You send out a flurry of calls to prospective sources telling them exactly who you are and what you want, and who to call if they want to check you out. Then the references call: This guy asked… and I told him…what the hell are you into? And when the sources call back, sometimes it’s at the office, a number you didn’t give them. Or maybe you did. Like any spook, you’re working a regular gig and snooping on your off time, which quickly runs you into exhaustion, gives the day a dreamlike tone, so that nothing can be counted on to be what is seems.

But that’s all right, because in espionage nothing is ever really quite what it seems. For instance, you’d think the main espionage targets would be in high and rarified circles -the board of directors, the comptroller, the company lawyers – and the spooks would move in those circles, like double-ought-seven, picking up Essential Elements of Information at the club. Not so. You can get all you want out of the board by planting a tape recorder and servicing it regularly. And the people you use for that aren’t the directors, but the janitors -cheaper to bribe, easier to bully -so why not send in someone posing as a slightly tatty reporter to scout out your security system? It’s not too farfetched: Everyone needs publicity, and reporters are privy to all sorts of confidences spoken “off the record.” A seasoned security aparatchik would check out a reporter as a matter of course.

Ex-FBI agent Dave Leopard, who heads a highly regarded security operation at Mary Kay cosmetics, knows this, and knows you know it. “In a sense, you have to watch everybody,” he says, sitting in his office near the top of the Mary Kay building on Stemmons, leaning back from his desk, from which everything -papers, appointments calendar, everything -has been removed. “And you deny access. Even if someone were to hire on to gather information for the competition -or just to sell to the highest bidder, there are a few entrepreneurs -you can still deny them access.”

So there are honest-to-God moles, deep cover agents, in industry?

“Companies will hire people to work in research and development, when in fact they could be working for some other like industry,” Leopard says, carefully framing his answer. “When you hire people away from other major firms, you have to wonder where they’re really coming from.”

And then there’s the old standby, the disaffected employee.

“If they’re working in a sensitive area, we are sometimes made aware of problems with employees. We have to look at where they’re working, and alert management to watch for a pattern of behavior.”

Leopard catalogs other security measures. Compartmentalization. Shredding the trash. Following up on leaks. And generally promoting loyalty as a by-product of treating people right. Just like any other espionage target. Except that in corporate matters -and this is what distinguishes industrial security from its heavy-handed military counterpart – all this activity has to be woven in with delicate subtlety. You can’t oversell to management without coming off sounding like a crackpot, and you can’t come down too hard on the rank and file with brain police under every desk without burning them out and driving them away, usually to the competition.

“It’s a challenge to make a fortress and still let your people feel warm and at home,” Leopard says.

So there it is, the outline of industrial security-the part that protects the information-worked out over decades in such industries as cosmetics and fashion design, introduced more recently in real estate, computer software and elsewhere.

So recently, in fact, that it’s never occurred to a lot of firms that they’re being watched. Or to a lot of individuals. And knowing this, you might find yourself sliding into the patterns of paranoia, retyping notes in simple code, making sensitive calls from pay phones, dropping false clues here and there. By the end of a fortnight of hanging around with these people, you feel like a complete hick. There’s no game to it anymore. You’re actually finding out more “secrets” than you want to know. So by your second meeting with Cofall, you’re actually on some face-off with the paranoia, going through all the moves, telling yourself-over and over – that they’re silly, and flashing in and out of a sense of giddy adventure, like a teenager dealing lids or a cub reporter eavesdropping on the closed-door school board meeting. The game is a hard addiction.

Again, a place of Cofall’s choosing. The dining room at The Mansion on Turtle Creek. Cofall arrives in a Delorean (you can’t see his Delorean in the dark, he explains later) and they won’t let you in because you’re not wearing a sport coat or a tie or something. So you go to another place again, a Chinese restaurant near Love Field. The luncheon crowd is gone. More small talk, a little gentle pumping for what you’ve learned so far.

“I brought along some things you might be interested in,” Cofall says, opening a formidable-looking Samsonite briefcase with a combination lock. “This,” he says, extracting a metal box about the size of a small cassette recorder, “is a voice-stress analyzer. It does the same job as a polygraph, only it reads minute changes in voice pitch, so you don’t have all those wires and the subject doesn’t know he’s being scanned. You set it to normal stress level and when it picks up additional stress these lights light up.”

A silence passes while you try to track the implications of this device as they split off in a dozen directions, and Cofall pulls out a couple of mikes and patch cords.

“See, you can plug it into your phone and scan conversation from your end. Or you can tape a conversation, run the tape back through the VSA and scan it that way.”

Lord, that means not only can you bug a room, you can also tell if anyone in it is lying.

“And this,” he continues, his cadence picking up into a well-practiced sales pitch, “is a portable telephone scrambler. It’s a two-element system: You need a device at both ends to scramble and unscramble. And here,” he pulls out a telephone and its cradle with a red light and a couple of switches on it, “is a tone-activated wiretap neutralizer.”

A what?

“It picks up a drop in voltage on the line. A tone-activated wiretap usually pulls about 20 volts. The neutralizer picks this up, warns you and compensates for the drop in voltage, shutting off the tap. Of course, for about $40, you can get a cheap detector that just replaces the mouthpiece on your phone and lights up if you’re being bugged.”

How come no one’s ever heard of this stuff? you ask as you drive out to the airport to rendezvous with an out-of-state businessman who has flown in to pick up his order.

“Well, the telephone company won’t let me advertise bugging sweeps in the Yellow Pages,” Cofall says. “They told me only the government plants bugs, and you don’t have any business sweeping for them unless you’re into something illegal.”

Yes, the phone company is well-known for its altruism, isn’t it? Cofall smiles.

“I met this lawyer once,” he begins. “I guess this is all right to tell you. 1 sold this guy a gun, and we were talking about wiretaps. I told him one way to plant a tap was to go in dressed as a phone man checking the switchboard. Secretaries never challenge phone men. I mean, no one challenges phone men. So anyway, about five days later this guy calls me and says he caught a couple of guys posing as ’phone company advance inspectors.’ Well, everyone knows the phone company doesn’t send advance inspectors, so he told them to leave.

“This guy was working on a damage suit. He’d been told how much to settle for. A little later he tells me the lawyer for the defendant gave him a call and offered to settle out of court for the exact amount. I mean, the exact amount. Too close to be coincidence.”

Cofall offers another service, besides weapons and debugging. His ad in the Yellow Pages lists “crisis management,” which is another inspired euphemism.

“Hostage recovery,” he says bluntly. “Kidnappings in South America and the Middle East -anywhere there’s oil money and unstable politics, you have an upsurge in kidnapping.”

Then he lays this real nightmare on you. It seems that if you’re kidnapped overseas, you -and your employer -are pretty much on your own. It’s been street lore since the infamous Sixties drug busts in Mexico, Colombia, Turkey and other places that the State Department isn’t going to help you out. Indeed, a department spokesman confirms that its official policy is to ignore the ransom demand, even if it means losing the hostage. When the agrarian reformers or the Saracen fanatics or the urban guerrillas or whoever gets tired of killing helpless hostages, the thinking goes, the kidnappings will stop. And for a long time, industry went along.

All that changed in 1979, when the Iranian revolution broke loose and trapped two engineers from EDS in a multimillion-dollar ransom demand. State Department policy offered EDS chief Ross Perot one option: Let his employees stay in Gasri Prison and rot. So Perot created an option of his own: Gather a team of commandos, hire a retired Army colonel to lead them, go into Tehran and bust them out. That operation was a masterpiece of innovation: Instead of relying solely on stealth, Perot’s men just increased the level of background noise by “arranging for a mob” and starting their own riot. It excited the imaginations of many corporate types wearied by daily facing the possibility of being taken off.

The problem here is the federal neutrality statutes, which keep Americans from using force in a foreign country. At the same time, the market is loaded with highly trained heavy violence experts, seasoned in operations -Phoenix, Blue Light, Delta Team-that the U.S. Government itself has fronted. The temptation to give way to frustration and capitalize on this resource is great, but it has to be resisted if you want to stay in business and out of jail. Cofall says he prefers to find the legal way, but the lore is common knowledge in the trade.

“You try to keep the team small and get them in and out fast,” he says. “If you’re going to pay the ransom, you have a bagman who’s wired and a radio man off site to relay the negotiations back to company headquarters and a medic standing by in the country.”

And if you don’t want to pay? Cofall relates dark rumors of a new trend in espionage chic: Hire a team to go in and rescue the hostage, then ruin everyone involved, and all that implies. “Five men ought to do it. Three with weapons, a medic and a radio man. But it’s risky, and it’s very expensive, and people don’t want to do it if they can avoid it; the multinationals already have such a bad reputation among the locals. And it’s illegal.”

The State Department, for the record, says Perot’s rescue was the only one of its kind they’ve ever heard of. But then, Perot announced what he’d done at a press conference as soon as everybody made it home. Unless you have an obsession to dig further, that’s probably all you’ll ever hear on the subject. Except that everything you need for drastic action -miniradios, silent weapons, gas masks, flak jackets, night-scopes, parachutes, the whole load -is available on the street in Dallas.

In any case, kidnapping is a reality the security types have to face calmly. “Crisis management should be the goal of every security division in every corporation,” says Mary Kay’s Dave Leopard. “To write and implement a plan that includes where to get ready cash, who to call in, how to proceed. In different industries you have different kinds of problems. Banking is the most prone because the money is right there.”

But we digress. And that’s easy to do when you’re tracking espionage, even superficially. It all laces together like the conspiracy buffs fondest fancies. The basic industrial security service is physically securing the plant. And even that can take you up to international scale, like the E-Systems engineers who are physically securing the Israeli border. Physical security melds into information security. Here again, in Dallas R-and-D shops, information that’s valuable to competitors is often valuable to governments with “interests inimical to the United States.” The FBI says technical intelligence tops the KGB’s priority list, and while they can’t say one way or the other if there’s a KGB station in Dallas, they do point to the strategic materials control list -about as thick as an Irving phone directory -of items we’d like to keep in and they’d like to take out -from computer chips to oil drilling bits -and about 60 percent of it’s available in Dallas. No one’s been caught here yet, but every now and then you hear about someone getting busted in California or Kansas or somewhere.

But that’s not the mainstream: The main energy appears to turn away from the dowdy Cold Warriors and toward the high-velocity industrial sector, where you don’t have to wait for cumbersome government procurement to turn a sensitive innovation into a classified one. In the private sector you can watch it happening. All you have to do is set up a library to read the white sources, keep a discreet recruiter on hand for gray sources and stash away a business card or two – and be ready to risk conspiracy prosecution – for the black ones.

Or, you can warp through all this and wire directly into the corporate medulla, the computer, where all the competition’s information – down to his junk mail list – is stored in a brain that has no judgment, no loyalty, no scruples. None. And neither, it appears, do an alarming number of the people who operate the things. In the newspapers, stories about teen-agers who dial up the line and blow up 10 years research have become a staple item. These are not malicious people: Like the computer, this new menace seems to have no direction at all, except to solve the puzzle, to make the machine do something, whether it’s printing out a naked lady or taking over a multinational. It’s all the same. So finding an idiot savant is no problem at all for an enterprising spook. You practically trip over them like winos these days.

People who ought to know better are finding this out too late. The banks learned it first. They’re closest to the money. Wells Fargo -the nation’s 11th largest -lost about $21 million to a two-year rollover. That’s one example. There are a shocking number of others. And as all this was coming up, the bankers found a loophole in their insurance: They weren’t covered if an outsider tapped the lines. It had to be an inside job, or the banks had to eat the loss. That got the banks interested in computer security.

And the number of outside jobs increased exponentially, hitting seemingly at random, spearheaded by a series of humil-iatingly easy penetrations that did terrible violence to the victims. Some kids at Dalton School in New York City, for instance, wandered into a Canadian financial data chain posing as PepsiCo of Canada. They didn’t steal any money, but while they controlled the machines they screwed up the files of two other firms. Motorola, for example, uses an otherwise innocuous TI computer terminal to pitch computer security by actually tapping into a bank line right before the eyes of enthralled audiences. The equipment to knock over a bank -or anything else – costs about as much as a low-grade used car. The bill for defending against a hood thus armed is a little under a half-million dollars, counting risk analysis, security and audit software, encryption and leasing for backup systems.

But, see, you don’t actually have to steal money or anything, directly. If you can get in, you can actually alter reality, create a new identity -background, references and all -out of whole cloth, like the gang of car thieves in California that stole cars and, plugged into the state computer, simply changed ownership records.

When you first hear all this, the initial impulse is to pretend it isn’t true. Then curiosity -or some self-destructive need to know-gets the better of you and you start asking, confirming. Most of your sources don’t want to be named. A few do. Leopard says, “Industry itself is very competitive.” Tyska says, “There’s no end in sight.” EDS doesn’t even pretend to be anything but a fortress, and says a lot of their business is sold, in part, on their extraordinary security. Which tells you more about the business climate than it does about EDS’ corporate philosophy.

Cofall sits across from you at a table in the Hilton Inn, your last interview before he has to disappear on some job. He’s just finished telling you about acoustic-wave generators, which put out random noise to keep spooks with laser mikes from eavesdropping off the vibrations of your windows-and he pauses while the somnam-bulent waiter goes back for a clean glass. You just have to ask, one more time, before you let go of your innocence. Is it really going on everywhere?

Cofall nods, perhaps a little sadly. “You know the voice-stress analyzer?” he says.

“The lie detector?”

“That’s the one,” he says. “Well, I’ve sold a couple to newsmen.”

A long pause, filled with a vision in which everyone is in the game, free enterprise run amok, the whole work force feeding off each other.

“So how do we get out of this sorry state?”

There follows a discussion that lasts for an hour, covering philosophical territory you forsook when you outgrew Sunday school. What it comes down to is a new religion, a cataclysmic fad in which the satanic Gordon Liddy/Super Fly Mafia-macho syndrome gives way to an obsession with integrity, and all at once people are getting off on being honest and playing fair. In short, the whole marketplace must be inhabited by boy scouts. Mind you, most businessmen are still as honorable as businessmen have ever been and you can win playing by the rules, even if no one else is playing that way. You just have to be more clever, quicker, employ better quality folk. But the hazard remains as long as people don’t mind using each other, and being used. The discussion ends on that somber note.

Any excursion into the cold -real or imagined – takes a little warming up afterward, with great care taken not to burn up on reentry. What you’ve seen is translucent; what you’ve heard is vague, deliberately scrambled in places by subtle phrasing-ambiguous. There’s a chance that everything you know is wrong. So you find yourself asking the question -the spook’s prayer -what does it all mean? And pondering over and over, who do you trust, and how far? And that high-voltage mistrust of everybody and everything, coupled with the sheer energy it takes to see the image through the fog, that, more than anything else, is the ultimate cost of the game. You might dwell on this, trying to lock in on some single fact that means only one thing, as you sit at your desk playingwith the “look to Litton for night vision”penlight and remembering Cofall’s smileas he told you, “The easiest way to bugsomeone is just to hand it to them.” Andyou have to smile, feeling half silly, asyou take the batteries out of the penlightand stash it in your desk. After a whileyou stop smiling and move it out to thegarage.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.