THE MAYOR of Dallas was trying to persuade the other 10 city council members to rise above politics.

The council was discussing the most racially and politically sensitive issue in city government: redistricting. After hearing minority plans that called for the addition of a third black council member and the end of white representation for Oak Cliff, Mayor Jack Evans presented his own plan. It would essentially leave the current districts intact.

“I hope this workshop will look objectively at this, ” Evans said.

“How can the mayor expect politicians to be objective about redistricting?” I whispered to a veteran city hall reporter.

“It’s objective, all right, ” he said. “Everybody objects. “

At-large council member Wes Wise objected to the implication that he couldn’t represent the interests of blacks. Don Hicks objected to the “resegre-gation” of his Oak Cliff district, implying that whites would leave the area if blacks had an overwhelming majority in his district. Max Goldblatt said he would see anyone in hell who said a council member had to be a certain race to represent a district. Black council member Fred Blair warned that Dallas is 30 percent black and 40 percent minority and will soon be 50 percent minority, and minorities needed more representation.

While defending his plan, which would leave Oak Cliff with a white council member. Mayor Evans asserted that a black could win an at-large seat on the council or even the mayor’s office.

This was too much for Blair, whose reputationfor compromise and negotiation is stronger than thatof the other black council member, Elsie Faye Heg-gins. “Let’s deal with the facts at hand. People don’twant to go to school with us. How can they vote forus?”

By the end of the meeting, Ricardo Medrano (the other minority member of the council) had yelled at Mrs. Heggins and stomped out of the room. It appeared that the blacks would have to take redis-tricting to the courts if they were to get a black district. “Objectivity” had yielded to simple politics.

But who could reasonably expect anything else? Rising above politics on redistricting was about as likely as giving downtown Dallas back to the Comanches.

Most observers and participants agree that Dallas; city politics is undergoing a transition. The creation of single-member districts, the rise of neighborhood groups and increased demands for participation by minorities mean more players at the table than ever, before. The time is gone when a few Dallas businessmen and civic leaders could decide who would be mayor and who would be on the city council, what would be developed and how city money would be spent.

Dallas has grown too complicated for that.

The time has also gone when the city council would respond to the city manager in the same manner that a rubber-stamp board of directors responds to a board chairman. In the old days, when Dallas was more of a homogeneous community with a monolithic power structure, city politics wasn’t really politics. You had a city manager who ran the city like a business, a mayor who usually was a member of the city’s power elite and a group of city council members whose goals were generally the same as those of the city manager and mayor. There was little horse-trading, coalition building or other political gamesmanship. The main business of the city council was simply to see that city government provided the necessary services and atmosphere to make sure that Dallas grew. They did. And it did.

But the city grew in more ways than anyone might have envisioned 25 years ago. Dallas has grown more politically and diversified ideologically. The council is no longer a group of like-minded citizens out to do their bit for civic service and then go home and forget about it. The council is now made up of a diverse group of people with different goals and widely different constituencies. The battle of the haves versus the have nots, that struggle that has gone on at some level as long as there has been civilization, has now moved squarely into the city council chambers. The council members who win the majority of the day-to-day battles in that struggle are those who excel at the mechanics and strategy of the game: politics.

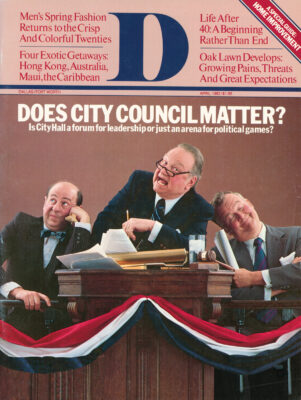

Every odd-number year Dallas elects 11 people to city council, eight from single-member districts, two at large and one as mayor. Their charge is to represent both their districts and the city as a whole. They’re supposed to make intelligent decisions on issues that directly affect the safety, health and comfort of 900, 000 people who live in 385 square miles of one of the fastest growing cities in the country. Those 11 people are given 13, 000 employees and an annual budget of around $500 million with which to work. Every decision they make is broadcast on the radio Wednesday afternoon and written up by two of the most competitive newspapers in the country on Thursday morning.

And although council members’ decisions affect everyone directly, few people bother to vote in city elections. Only 73, 000 votes were cast in the last mayor’s race. An average of 17 percent of the registered voters decide who is going to serve on the council. A few hundred votes can determine who is elected in a single-member district.

For $50 a week, expenses and a shared office, a council member gets the right to sacrifice his or her business career or job in order to put in the minimum of 40 hours a week required for city business.

They are expected to spend hours poring over zoning charts, spend their lunch hours speaking to civic groups and their weekends secluded on budget workshops. They have to make decisions that could drastically affect their constituents’ homes and businesses. They are supposed to act in the name of the “common good” on a bewildering array of municipal, state and federal laws, and make decisions on everything from a low bid on car batteries to plans for mass transit.

To perform this Herculean task, we send to City Hall a group of people with widely varying amounts of experience, astuteness, savvy and skill. In the old days it really didn’t matter how skillful or astute any individual council member was. There was a community consensus, and that consensus prevailed in the council chambers. Council members who weren’t up for it got carried along for the ride; council members who were actively against the consensus got politely run over. But now it really does matter who fills each city council seat. Each individual council member has more potential to influence the system than ever before.

To determine how well each council member is performing his or her job, we interviewed a broad spectrum of close observers of the council -civic leaders, politicians, journalists, neighborhood activists, city staff members. The following analysis of the council members’ performance in the political system is based on those interviews.

Jack Evans, mayor, Place 11, at large. Talk about Jack Evans, president of Cullum Companies, Inc. (which owns Tom Thumb and Page Drugs), almost invariably begins with a comparison with his predecessor, North Dallas developer Robert Folsom. Evans says he is more of “a team player” than Folsom. Insiders agree with that, but wonder whether Evans can exert enough leadership. It appears to be a choice between being well-liked and making hard decisions that may not be popular.

“Being mayor is a political job, but he doesn’t always understand it’s a political job, ” says one insider. “Evans’ primary thing is that he searches for consensus. He wants to have as many votes on an issue as he can. Folsom would be willing to get six [a majority of the 11 members of council] and then stop. Evans wants to avoid confrontation. He’s not a conflict person. He looks for the sources of disagreement and goes behind the scenes, and works individually with council members.”

The result, the insider says, is that Evans hasn’t been as effective as he could be. He isn’t identified with any particular issue, and in that sense, is untested. The era of the major projects may be over for Dallas, and in the past, projects such as the water system, the airport, the convention center, the new City Hall and Reunion Arena have focused attention on the mayor’s office.

Evans points out that as mayor he cannot control the city council the way the chairman of a company board can exert leverage. The mayor has only one vote, as do each of the council members.

Still, a lot of power and prestige is attached to the mayor’s job, and Evans’ handling of the council debates has been criticized by observers.

“Folsom always spoke last; he always wanted the council to know where he stood, ” says one watcher. “Evans very often speaks first on controversial issues. Sometimes it works; sometimes not. ” In the case of the regulation of halfway houses for paroled convicts, the mayor narrowly missed going in the opposite direction of the council, which passed restrictive measures on where the houses could be situated.

“The most difficult responsibility is being understood by the media, ” says Evans. In what must be a record for geniality, Evans says in general, he hasn’t been disappointed in his treatment by the news media.

“Jack doesn’t grasp the need to be careful in talking to the press, ” says an insider. “His tendency to think out loud to the press gets him taking a position earlier than he needs to. There’s nothing wrong with not taking a stand on an issue from the earliest point. “

“It’s a good deal for reporters, ” says a City Hall journalist, “because each one of us gets a different story. He never tells the same story twice. He lacks an ability to focus on issues. “

Evans’ eagerness to meet with all people turned into a political pitfall when the president of the Dallas Gay Alliance, Don Baker, asked him to speak at one of the group’s meetings last summer. Baker said he phoned the mayor and confirmed the meeting the first Monday in July. When Evans came to the meeting, “he presented a fabulous program, ” Baker says. “There was a note of seriousness about our needs and concerns. “

The heat came when the gay group announced Evans’ receptiveness to their goals, and Evans denied that he was invited by Baker or even knew he was going to attend a gay meeting. Instead, he says, council member Ricardo Medrano invited him to what he thought was an Oak Lawn town hall meeting. He would not have attended if he had known it was not a town hall meeting.

“That is a flat lie, ” says Baker. “Jack Evans and I had it perfectly clear. He may have talked himself into believing that. “

Evans says he does not want anyone to think he condones the sexual preferences of homosexuals.

The story is cited by a business insider as a perfect example of Evans’ naivete. But it is also an example of his willingness to listen to everybody. It’s hard to imagine Robert Folsom falling into such a problem.

Evans is praised, on the other hand, by a business insider for making a firm stand against a third black district.

“To create a third one is to create a ghetto, ” Evans says.

That thinking aligns him with Don Hicks, the white council member from South Oak Cliff, who fears his district’s 70, 000 whites will abandon the area if it is put in a “safe” black district.

Evans won no favors with the black community after a January redistricting hearing in which 70 people, representing a solid cross section of the black community, from the NAACP to voting groups to ministers, called for a third black district. Evans infuriated the black community when he was quoted in papers the following week as having said the group wasn’t representative of the black community. Pickets were set up at some Tom Thumb grocery stores, but were later removed.

Evans continues to assert that a third black district is not sought by all blacks, and that many of his black friends privately tell him the district is not needed. Evans won’t name those friends for fear of subjecting them to black pressure. But it is a classic case of politics tangling with race and organized community groups.

Evans’ design for redistricting assures the present minority representation of two blacks and a Mexican-American. It leaves Don Hicks’ seat intact. And it practically assures a lawsuit from the blacks. There was no way for Evans to bring about a consensus, short of restructuring the council, which would require a city-wide vote on a charter amendment.

Evans has yet to make an issue his own, but the downtown arts district may be shaping up as an issue where his powers of persuasion could be useful. Evans was a leader in passing the 1979 bond issue that created the arts district. Whether the district becomes an architecturally interesting mecca for pedestrians seeking shops, restaurants and art, or a jumble of high-rises, can hinge on Evans’ ability to draw the developers, architects and business people together. The issue could easily become the test that shows us what kind of leader Evans is.

SID STAHL, Place 9, at large. “Stahl impresses me, ” says one journalist. “He’s a racehorse in a team of mules. ” Stahl had a grasp of city problems from his experience serving as head of the Park and Recreation Board.

He has picked some highly visible issues – the arts, transportation and the redevelopment of South Dallas -and worked hard on them. Each issue tends to affect Dallas as a whole, and Stahl’s leadership in them makes him a possible future candidate for mayor, most insiders say.

Stahl’s soft spokenness does not mean he is soft on issues. During the propertytax revaluation problems a year ago, Stahl was for cutting the council’s losses and going back to the 1979 tax valuation rather than prolonging the city’s problems. He lost by one vote. He also suggested that then-city manager George Schrader resign because of the inconsistencies and contradictions on the tax rolls. That was almost unthinkable to a city that thought of itself as being one of the best-managed in the country.

“Stahl enjoys results and is frustrated when others won’t work as hard as he does, ” says an insider. He is interested in what is achievable and doesn’t like idealistic stands.

Stahl’s greatest asset, his strong North Dallas support, can sometimes be a liability in the minds of South Dallas members of the council. The at-large position has been characterized as simply another vote for the north in a city that has become increasingly divided between a white, well-to-do, rapidly developing northern half and a lower-to-middle class, increasingly black and brown southern half.

“Stahl’s campaign contribution list weighed a pound, ” says one insider. “He even turned down money. “

No one questions Stahl’s honesty, but his abstentions on some zoning cases cause concern in some quarters. Those abstentions come because Stahl is a law partner in Geary, Stahl & Spencer, and Joe Geary is Robert Folsom’s lawyer.

When Stahl proposed the redevelopment of the southern half of Dallas to the last city council, he had to persuade Elsie Faye Heggins that it was not a scheme to run heavy industry into the south without concern for the residents. Heggins came around, but Stahl was visibly shocked by Folsom’s initial reaction to the proposal, which was roughly, “We don’t want this to be seen as meaning a halt to North Dallas development. ” Stahl today insists that Fol-som was always supportive of the project.

Stahl must still show his allegiance to the North Dallas business community, which insists on business growth above neighborhoods. To one insider, the motivation for the southern Dallas redevelopment is political and furthers Stahl’s appeal to the city as a whole. Another skeptic suspects that specific business interests were behind the southern redevelopment, but Stahl steadfastly denies there is any vested interest behind the redevelopment, which calls for issuing revenue bonds and giving tax breaks to businesses that move to the southern half of the city.

Rolan Tucker of North Dallas voted against the government incentive to business, calling it artificial. Max Goldblatt, whose district might benefit from the project, called it undemocratic. Neither believes that business should be given any special government help.

One sign of Stahl’s allegiance to North Dallas came with the Love Field noise controversy. When the issue seemed to divide on whether business should be restricted at Love Field to assure more quiet in the neighborhood, Stahl voted against restriction.

Whether you believe Stahl is making decisions with an eye to being mayor or an eye for the best interests of the city, depends on your point of view, of course. To some observers, Stahl is too narrow and restricted in his selection of issues to be the kind of leader the city needs. But transportation, others point out, is perhaps the most important problem confronting Dallas. Within five years Dallas will face the same massive traffic snarls that Houston has to deal with. As chairman of the Interim Regional Transportation Board, Stahl is in a position of important power and influence.

WES WISE, Place 10, at large. Wise is in many ways a contrast to Stahl. Where Stahl is the soft-spoken, analytical, well-to-do North Dallas corporate lawyer, Wise is an outspoken populist, probably the brokest member of the council. Where Stahl narrows in on a few significant issues, Wise is a scatter-shooter.

“He plays to the gallery, ” says a business insider. “He’s trying to say what people want to hear. “

With little money but strong name identification from several years of radio sports casting, Wise upset the establishment apple cart in 1971, beating a Citizens Charter Association candidate to become mayor.

He is thought to listen to a broader range of people, and is an important vote on minority issues. Both Wise and Lee Simpson worked to find some compromise on the addition of a fourth black district, but could come up with nothing that would not require a charter amendment.

Some observers think Wise will run for mayor again, and that he is more concerned with how decisions will be looked at than how they will affect people.

“He is the consummate political animal, ” says one watcher. “If you listen to him at a briefing, he looks more at what the headlines are going to say. There is some parallel to Reagan; both have made affability into a political art form. He is in a nice position to cast himself as an Anglo populist.”

But black political organizer J. B. Jackson credits Wise’s election as mayor as a “turning point” for the representation of black issues before the city council.

Most insiders think Wise lacks influence on the council and is not taken seriously by other members. The trick will be keeping his balance, says one journalist, who imagines Wise standing on a breadboard on top of a rolling pin that’s on top of another breadboard that’s on top of another rolling pin.

Rolan Tucker, Place 4, Central and North Dallas. One observer calls Rolan Tucker the happiest man on the council because he’s the least frustrated. He represents one of the most homogeneous districts on the council. He tends to side with developers on issues where neighborhoods come into conflict with them, but he has a strong sense of his constituency. He has been active in developing a neighborhood crime-watch program to stop the burglaries that plague his district. He has also carried his crime-watch techniques into Elsie Faye Heggins’ black district.

Tucker, above all, is not looking toward the next election or another elective office. Tucker is quiet and observant during council meetings and is generally not a speech-maker.

He has been criticized for being insensitive to neighborhood issues. He is against a third black district.

“I still do not see representation in terms of black and white, ” he says. “I spend as much time on the 10, 000 blacks who live in Hamilton Park as anyone else, and 1 got 80 percent of their votes last time.

“I really believe a black could represent an all-white area, ” Tucker says.

To the neighborhood forces, Tucker represents a vote for unbridled development. But Tucker also leads a fight to buy expensive park land north of the LBJ.

“Rolan is listened to by the council, ” says an insider. “He’s disarming to those who don’t watch a lot but he’s got a lot of savvy, and has well-reasoned arguments. He was able to convince the council to vote to buy park land. He was a supporter of the Tollway extension. “

Tucker also voted against the deletion of portions of the cross-town expressway, an issue that polarized the neighborhood groups against development forces. On that one Tucker lost Joe Haggar, the other North Dallas councilman, who would seem more naturally allied with Tucker.

Tucker is not considered to be blazing any new trails in city government, nor is he particularly political. He could have a close race next year, but if he loses, he could happily go back to his job as president and chief executive officer of Metropolitan Savings.

Joe Haggar, Place 3, Northwest Dallas. “Joe Haggar is Rolan Tucker one generation more liberal, ” says an insider. “I think he’s terrific; exceedingly hard-working and highly disciplined, very conscientious and surprisingly flexi-ble, not rigidly set. “

Haggar worked very hard behind the scenes to bring about a compromise that was acceptable to both sides of the Police Review Board. The minorities on the council wanted greater investigative powers for the board to look into police shootings of minorities. The police wanted no board at all. The resulting board has few powers and has probably satisfied no one.

Haggar’s assessment of the present council is as much a reflection of his own qualities as much as those of the council.

“I believe this council exercises more patience in listening to people. “

Haggar is sympathetic to the lack of opportunities blacks have had, but he doesn’t believe they should be given a third district. He believes that a black could win an at-large seat, given enough organization. Unlike Tucker, he voted for redevelopment of southern Dallas. He says he believes in the free-market theory, but he doesn’t mind government helping out as a catalyst in improving the southern half of the city.

Other members of the council respect his ability with figures. He challenged some city staff figures on a proposed bus-fare hike, and won some concessions for the riders.

“Wise would have taken a political approach to that, ” says one watcher. “Hag-gar tends to approach the problems of the city like business problems. “

One observer said he was disappointed in Haggar for not having a more-aggressive attitude toward city-wide needs. What is fairness and openmindedness to some is lack of aggressive leadership to others.

“Joe doesn’t come up with great ideas, but he has a workman-like mind, and he’s well-prepared. He’s the kind of person the mayor would like to be. “

LEE SIMPSON, Place 5, Northeast Dallas. Simpson is a young lawyer who beat an East Dallas Chamber of Commerce candidate by door-to-door canvassing. He’s young, ambitious and fearless.

There’s talk that he might run for Congress out of the 5th District some day, and Simpson doesn’t rule out running for other offices. In a council of citizen volunteers to whom being “political” is a bad thing, Simpson is frank.

“The Central Expressway is not a technical problem, ” he says, “it’s political… Everything we do is political. “

Simpson was with Max Goldblatt in voting against the building of four elevated lanes but more as a vote of conscience than anything else.

Simpson is allied with neighborhood preservation groups and has a strong sense of his constituency, much to the frustration of those who think he should take a larger view of things.

The larger view of things often means development that could harm neighborhoods. Simpson was particularly effective in blocking the cross-town expressway that would have torn through some of his East Dallas neighborhoods. Under the old council, he got nose to nose with Robert Folsom. This appears to suit Simpson, who is something of a maverick.

But he’s a maverick with a mastery of detail. “His range of knowledge about obscure zoning things is impressive, ” says one council watcher.

Simpson’s most-spectacular feat was “almost single-handedly getting the homes in his district reappraised” during the tax revaluation problems, says one insider.

Because so many people in his district own modest homes that are soaring in value, Simpson has to work hard to protect them.

He sees himself as faced with some of the same problems as Elsie Faye Heggins: protection of neighborhoods, constituent participation in government.

He notes that the southern districts voted against the downtown arts district but lost because they simply didn’t have the voter turnout the northern districts had. He shares the concern of minorities that not enough minorities are being appointed to the city’s boards and commissions.

Of all the grass-roots politicians in the council, Simpson seems to be the most effective. He is especially concerned that the city manager does not control the council agenda. He was critical of George Schra-der, the previous manager, for giving only his staffs recommendations without the reasoning that lead to the recommendation.

Simpson’s critics say his policies could lead to “no growth. ” But no one accuses him of being a lightweight. He does his homework.

Simpson recently resigned from his law firm, Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld, citing the potential conflict of interest because the firm wants to serve as Dallas’ Washington lobbyist. The firm includes Robert Strauss, former chairman of the National Democratic Party and one of the most important Democratic power brokers in the country.

FRED BLAIR, Deputy Mayor Pro Tern, Place 8, Southeast Oak Cliff. Blair, a successful Realtor, is inevitably compared to Heg-gins.

“He’s in the unenviable position of trying to deal with the whites on a peer basis, but being pulled by the efforts of Elsie Faye Heg-gins, ” says one close observer to city council politics. “He’s had to spend a lot of his time maneuvering between two extremes rather than spending his time behind the scenes. “

The question seems to be whether Heg-gins drags Blair into confrontations he would rather avoid, or whether he is his own man, working his own way.

“Being a little quieter makes him more effective, ” says one watcher. “He knows when to fight and when not to. “

If to some of Heggins’ constituents, Blair is too moderate and conciliatory, to some white observers Blair sees things too often in terms of race.

Blair was recently critical of Warner Amex, the city’s cable television company, for not moving swiftly enough in hiring minorities. Max Goldblatt accused Blair of harassing the company.

Blair says the current city council is good because it is more open than the previous councils and is not as quick to go behind closed doors. He believes the council is at the mercy of the city manager’s staff and council members need assistants who are capable of getting information independently of the staff.

“The old council only wanted to hold down taxes and let the city manager run the city. We’re gonna have it again if we’re not careful, ” Blair warns.

It was partly Blair’s pressure and that of other southern district members that got Charles Anderson appointed as city manager. Blair notes with approval the increase of minorities and women on the city staff.

He is a little touchy about comparisons with Heggins, especially her grass-roots support in her Tuesday meetings. But Blair, too, is busy in his district, constantly speaking at meetings. Blair has a high degree of identification with black business groups.

Although Jack Evans was a “breath of fresh air” after Folsom, Blair was upset with Evans’ charges that the call for a third black district was not truly representative of the black community. “It was out of character, ” he says.

ELSIE FAYE HEGGINS, Place 6, South Dallas. With her regular Tuesday-night meetings at the Martin Luther King Center, Mrs. Heggins, who sells real estate, commands a grass-roots organization that will probably make her unbeatable in the next election.

The question is whether she has been effective in getting things done for her constituents.

“She is a great politician but a lousy government official, ” says one insider. “She is consistently unprepared; she asks questions about material in front of her and doesn’t do her homework. She has a high degree of political visibility in her district and elsewhere, and she’s very available to her constituents. She means well but she’s not effective. “

Others are less quick to criticize. Councilman Rolan Tucker says she has been well prepared this year and addresses issues directly.

To many in the council, Heggins’ positions are set in concrete. She would not retreat on the question of drainage of Lower Peaks Branch, holding out for an expensive plan that no one on the council could vote for. She is similarly criticized for getting too far out in front on the Bl plan for redistricting, which would give blacks a third seat on the council but would damage Medrano’s district. Heg-gins insists that Medrano could carry the district because of his already proven ability to forge a coalition of blacks, browns, gays and labor.

To many council members Heggins brings up the issue of race too often. To Heggins, the under-representation of blacks on city boards and commissions is a travesty.

“I almost pleaded in executive sessions for more blacks on the transit board, ” she says.

The Interim Regional Transit Board consists of 25 members from the county and city. Only two are black, although blacks make up 65 percent of the bus ridership in Dallas. She is a frequent critic of hiring policies in the city staff, and is concerned with the inability of minority contractors and vendors to win city contracts. This further agitates Medrano, who is on the city’s minority contracting committee.

Heggins’ weekly meetings strike some council members as unnecessary and too political. They say they have other ways of knowing their constituents. To Heggins the meetings are vital ways of getting people involved.

“Heggins is one of the first grass-roots politicians this city has had, ” says an observer who has watched her carefully. “The halfway house ordinance is as restrictive as it is because of Mrs. Heggins. She pulls the debate over her way; the amphitheater won’t be in Fair Park because of Mrs. Heggins. She is a fairly representative spokesman of the black community, and that is a gauge of how far apart this community is racially. “

“Her confrontational style does not produce the results of George Allen [a previous black council member under the old at-large system] who was an expert at trading. She doesn’t know how to deal politically with a Joe Haggar or a Rolan Tucker behind the scenes. “

Ricardo Medrano, Place 2, North Oak Cliff, West Dallas and western North Dallas. Medrano will always be running for office, one theory goes, because the generic Medrano signs are all over town. Ricardo’s brother, Robert, tends to be a little more aggressive on the school board than Ricardo at city council. But because he is the only Mexican-American on the council, Ricardo’s word carries weight, says another insider.

“Elements of the community want me to be very militant; but the best way is to do your homework, work behind the scenes and try to convince your colleagues, ” says Medrano.

His community constitutes a mixture of browns, blacks, gays and laborers. Medrano worked hard to win the endorsement of the Dallas Gay Alliance, and to back up their endorsement, appointed two gays from the alliance to city boards. Medrano’s father, Pancho Medrano, is a long-time labor organizer. Politics isn’t exactly a civic duty to the Medranos, like it is for Haggar or Tucker; it’s a way of life. The Medrano clan does it for fun.

Medrano’s priority is housing. He believes that previous administrations did not do enough to make federal programs for housing work. He is trying to get prefabricated “granny cottages” approved for manufacture and use in his neighborhood. The units contain 800 square feet and can serve as housing for elderly relatives or as modest rental units. One insider questions whether Medrano has been effective on the council’s housing committee.

Observers have a hard time getting a fix on Medrano. They see him in some ways as the most politically minded of the council. When the cross-town expressway threatened to tear through Little Mexico, Medrano mobilized the votes of Elsie Faye Heggins, Don Hicks and Lee Simpson to get it stopped. And he offered to trade his vote for other issues the members wanted. Although vote trading goes on all the time in Congress, this blatant appeal upset Stahl and other members of the council who adhere to the ideals of deciding each case on its merits rather than on political considerations.

Right now Medrano’s worst foe on the council is Elsie Faye Heggins, whose determined support of the Bl plan for redis-tricting could gut Medrano’s district of minorities, reducing it to 54 percent, not enough to make it a “safe” seat.

Medrano gets most upset at what he considers to be Heggins’ “grandstanding” for the poor and the oppressed.

Medrano used to be a leader of the Brown Berets, but he says those days are over, waving a hand at his conservative coat and tie.

“You’ve got to change your style. “

Don Hicks, Mayor Pro Tern, Place 1, South Oak Cliff. Hicks is serving his third and last term on the council. His call for preserving South Oak Cliff, which has about 70, 000 whites, for a white representative has so tar been successful.

The call is particularly frustrating to Heggins and Blair, who wonder why it is wrong to guarantee a third black seat, but right to guarantee Oak Cliff a white seat.

“Bl is racially oriented and has no connection with Tightness, ” Hicks says. “It discriminates against browns. “

Hicks says he is against taking the white representation out of Oak Cliff because it would end investment in the area. “I come on to them as a racist, those who don’t know me, but as a minister I helped arrange summer camps for blacks. “

Hicks points out that his sons-in-law are Mexican-American and Filipino, and that he holds his real-estate license with a black man. His son was the only Anglo in his grade school class.

“If I’m a racist I wouldn’t be living in Oak Cliff, ” Hicks says.

Hicks is seen as being moderately effective for his district. He is strongly tied to the Oak Cliff Chamber of Commerce.

He was in favor of Sammons over Warner Amex for the television cable franchise, and Goldblatt accused him of beating a dead horse when he began questioning whether Warner Amex had lived up to its contract obligations. But he’s been joined by other council members on that issue now. Hicks, says insiders, doesn’t seem to have an agenda as a whole, though he’s very concerned about Oak Cliff development. He welcomed Sid Stahl’s program for southern redevelopment with open arms.

MAX GOLDBLATT, Place 7, Southeast Dallas. Goldblatt began running for the city council in 1968 and never stood a chance until the advent of single-member districts. But in the meantime, Goldblatt was council gadfly. Now that he is in the inner sanctum, he continues to sound off.

Some of Goldblatt’s ideas have sounded pretty screwy, such as the suggestion of using a helicopter to lift disabled cars off North Central Expressway.

Almost any group needs to have a Gold-blatt to deflate egos and liven things up. But too often Goldblatt’s speeches begin with, “I know that what I am about to say won’t make a bit of difference to this council… ” It has become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

One of Goldblatt’s best moments recently was the proposal to scrap the expansion of Central Expressway and build a monorail designed by Disneyworld. It was just the sort of idea that might actually capture the imagination of Dallas, which is not inspired by the cheapest, supposedly most practical form of mass transit: buses.

When he is not holding forth in city council or lobbying the press, Goldblatt holds forth in his jumbled hardware store in Pleasant Grove. It is as close to the old-fashioned cracker-barrel atmosphere as can be found in the city.

Goldblatt hates any sort of tax incentive for business, and he opposes public housing. He is particularly proud of the building of 2, 800 units of low-cost private housing in his district.

Goldblatt’s biggest problem, observers say, is that he doesn’t listen and he isn’t interested in building a consensus.

That is the Dallas city council. Its members probably represent a broader cross section of people than ever in the council’s history. City politics is becoming messy and unpredictable as the city begins to fill up its boundaries.

There is still room for development, but more and more of that is going to occur in northern suburbs outside of Dallas’s city limits. Essentially, the city of Dallas has left a frontier philosophy of expansion and turned inward on itself.

Recently a white commercial real estate broker found himself at Elsie Faye Heggins’ Tuesday-night meeting, asking for her vote on a zoning issue that would downgrade his North Dallas residential street. He didn’t have the support of his own council member, Rolan Tucker, because Tucker doesn’t want to dilute the city’s master thoroughfare plan. Mrs. Heggins said she would support the man’s request, because he had the support of many of his neighbors. And she asked if he and his neighbors wouldn’t support more black issues. The man won his case at city council meeting the next day.

Such battles are making the comparisonof the city council to the board of directorsof a corporation obsolete. Politics is having its day in Dallas.