WHEN DALLASITES look back on the Seventies, they think of “The Schrader Years. ” Which might seem a bit ironic. George Schrader, whose years those were, was merely city manager. He never was elected to anything.

And the job he did hold was, supposedly, completely apolitical. He was the analyst, the objective, nonjudgmental bureaucrat; according to the city charter, he had no more influence on policy than a desk calculator.

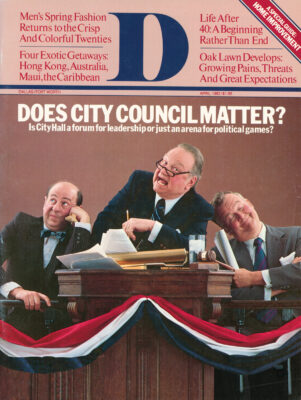

But if you saw Schrader work the City Council in those years, you had to know better. If you saw his sleek head jutting Gibraltar-like above that suit of corporate blue wool, with the crisp white shirt and the matching hankie peeking exactly one quarter of an inch above his breast pocket; if you saw his Forbes cover-guy smile as he shot things past the council so fast that the members had to find out about them after the meeting-things the members didn’t understand and didn’t even worry about understanding, because George said it was all right -then you just had this feeling that George Schrader could have gotten along perfectly well without those guys at the semicircular table.

You wouldn’t get that feeling watching Chuck Anderson, the 41-year-old country boy who’s been filling Schrader’s shoes for six months now. Indeed, you’d almost get the idea that Anderson works for the City Council.

First the obvious signs: Anderson doesn’t soar above the council members like an eagle. He darts among them like a sparrow, shooting his gaze left and right, peering warily from beneath those bushy brows of his.

Is any of this important?

Yes. Because the city manager, through what he does and what ’ he chooses not to do, has more influence over the city than any other official. He cannot decide matters of policy, but he has a big say in what policy areas will be discussed. He cannot settle debates, but he can start them and referee them. He is, in effect, “counselor to the council, ” city council member Lee Simpson notes.

Anderson, like Schrader, quite likely represents an era in Dallas history. When he leaves office, if he can survive as long as his predecessor, there will be another political stage under the city’s belt.

I’ll bet that it will be called “The Transition Years, ” in which Dallas changes from a white, business-oriented city -a city run by the elites -to a pluralistic city in which business leaders, neighborhood groups, blacks, Mexicans and who knows who else battle and bargain for larger shares of a pie that will stay just about the same size. Sometime in the not-too-distant future, City Hall may actually be a city dominated by a coalition of “minority” interests.

How well Dallas survives those transition years will depend, to a great extent, on Anderson’s ability to juggle those interest groups, to get each of them to help accomplish whatever is best for the city. And, incidentally, to keep his job in the process.

This is an argument that’s easier to make in reverse. Take, as an example, The Schrader Years, which might aptly be titled “The Final Years of ’Dallas, Inc. ’ “

Schrader was proud of Dallas’ image as the city run like a business. “A city government is like GM or U. S. Steel, ” he told Time magazine around this time last year. In a sense, he was right. Much of city government is business: water, sewer, streets and vehicle maintenance, for instance.

As a practical matter, it meant that many of Schrader’s greatest achievements were related to business. He helped spur Dallas’ meteoric development by private firms and made Dallas one of the hottest cities in America for corporate relocations. He helped revive a downtown business district that had been stagnant for years, perhaps indirectly speeding the rehabilitation of in-town neighborhoods.

He also engineered complex deals between the city and various firms, the most intricate being the Reunion Arena project that combined city and private funds to redevelop an entire quadrant of downtown.

From his appointment in 1972 until the turn of the decade, Schrader seemed to personify Dallas, as a government and as a state of mind. The city grew, and so did city government – from a budget of $208 million in 1972-73 to $549 million in 1982-83. Each, the old Dallas state of mind said, was growing smoothly, efficiently and in the best interests of everyone.

When Schrader took over the reigns of city management from the sleepy administration that preceeded him, he was the right man for the times. Schrader has been credited with awakening city government to the most pressing problem it faced at the time: redevelopment of the central city and the need to do something to deal with the flight of the middle class to the suburbs.

Ironically, the very growth that he helped engineer finally outran Schrader. It does not diminish his intellectual and administrative achievements to say that by the time he left office, city government had outgrown his centralized administrative techniques. Nor does it doubt his good intentions to say that the growth in political activism by formerly silent minorities outdated Schrader’s style of working with his bosses on the city council.

The city charter gives Dallas’ city manager full responsibility for, and authority to, execute the policies of the city council. Schrader, with his immense store of personal energy and elephantine memory, chose to run things pretty much on his own. “It was sort of a joke, back around 1980, that the assistant city managers didn’t really do anything, ” said one council member.

Under Schrader, the city’s 32 department heads were all directly tied to the city manager, like limbs on a puppet. “He pretty much held all the reins and wanted to manage everything, ” recalls Councilman Fred Blair.

Schrader’s style meant that in areas where he wanted to accomplish things -development, for instance-he could move like lightning. But while he was concentrating on building Reunion Arena, he could not devote much attention to the motor pool or the tax department. Several council members say Schrader’s methods also led to a false sense of security -his department heads were left pretty much alone unless there was news of problems in their agencies. There wasn’t, as a rule, so Schrader and the council assumed that things were fine.

Looking back, that sort of complacency seems incredibly outdated. In reality, it is as recent as 1980. Two things conspired to shatter the self-satisfied stillness of municipal debate in Dallas: A new city council took office, and citizens got the first inklings that if Dallas was being run like a business, that business might be Chrysler instead of GM.

The fears of “Chryslerization” were raised first by the discovery that the city had not even tried to serve thousands of misdemeanor warrants and citations, and that Schrader’s office planned to give that job to the police department even though police officers said they had no time to serve warrants.

Far more significant for Schrader’s future and the city council’s, was the revelation in the summer of 1980 that the city’s eight-year program to make tax assessments throughout Dallas more equitable had resulted in a $1 billion gift to local businesses, through undervaluation of business personal property.

The story came out bit by bit and got worse as it went along. By September, two days before the new city budget was to be adopted by city council, the administration had more bad news: The tax assessors had overestimated the value of taxable property in Dallas by $1 billion.

It got even worse. In January, the council learned that there had been still more mistakes in the tax rolls, mistakes that would require a $3 million adjustment in the budget. Mistakes that Schrader had known about for almost two months, without informing the council members.

Indeed, as the public ordeal by newspaper headline continued, council members began to feel that Schrader was not being very businesslike.

“He would think that he had the correct figures and then the next day he would come up with some new ones, and that was very hard on the council, ” recalls Councilman Don Hicks. “It looked like our credibility was on the line. “

The councilmen got to worrying. Hadn’t Schrader been warned about problems in the tax office as early as 1978, through an audit report he dismissed as being written by a “social planner type”?

Hadn’t he assured them, when the story first broke, that everything was okay, it was all no big deal?

Troublesome questions, those, even if the council members thought along the same lines that Schrader did. Which, for the first time in almost a decade, they did not.

The 1980 council included eight new members. Half of the newcomers were the first of the true single-member district representatives; the first in a long while not elected by Schrader’s friends in the Dallas Citizens Council. They represented minority interests, in both the racial and geographical sense of the word.

The mere presence of so many rookies on the council broke Schrader’s rhythm. He was accustomed to dealing with councils full of veterans who didn’t need a lot of explanations.

And the newcomers wanted to examine more closely the policy issues inherent in many of their day-to-day decisions; to examine even the premises on which Schrader had based his actions so long and so successfully.

Schrader left office on September 30, and officially retired on January 1. There was a general round of applause and praise for the man who had worked so many 18-hour days for so many years, who had such an encyclopedic grasp of city finance and operations. No one wanted to say a bad word about George Schrader. Indeed, council members still avoid public criticism of him.

In a sense, however, the very selection of Charles Anderson -who for 16 months had been an assistant city manager under Schrader -was a refutation of Schrader’s style, if not his substance.

When the council members who selected Anderson by a 6 to 5 vote are asked how he differs from Schrader, they have two responses: Anderson is “more open” and more willing to “delegate authority. “

It is safe to assume that the council was looking for such qualities when it picked Schrader’s successor. Under the old regime, for instance, Schrader would present the council with his recommended city budget a few weeks before it had to be approved. Anderson’s budget is coming out like the dance of the seven veils, with an eight-month series of public hearings and staff briefings. “We have insisted on it being more open, ” Councilman Max Goldblatt says. “We set those ground rules before we ever hired him. “

Anderson also has enlarged the briefing packet given to council members before each meeting, including virtually all relevant background material. Schrader, council members complain, would sometimes neglect to include enough information for them to ask intelligent questions about a subject. Simpson says he thinks Schrader often did not give the council the full benefit of his wisdom. “I always felt we had the ability to get whatever we wanted, as long as we knew what to ask for, ” says Councilman Joe Haggar. But, he added, Anderson gives the information without being asked. “He doesn’t catch you by surprise, ” agrees Mayor Jack Evans. “He conditions you for whatever action he’s going to take before he takes it. “

The extra information also is but one sign of the changing relationship between manager and council.

Anderson has had to be much more middle-of-the-road than the minority groups on the council, at least, viewed Schrader as being. “1 am very careful not to get in the middle of their political differences, ” Anderson says. He has little choice, given his tightrope position between the volatile voting blocs on the council; unlike Schrader, he cannot afford to ally himself with any political faction. Whoever is on top today could be toppled tomorrow.

Dallas’ strongest political undercurrent is between the haves, who have run the city for a century, and the want-to-haves, the blacks and browns. If trends shown by the 1970 and 1980 censuses continue-a significant if, considering the return of the middle classes to the inner city -Dallas’ “minority” groups will comprise more than 50 percent of the city’s population by the 1990 census. Anderson knows this; his final pitch to the council before he was appointed city manager included a pledge to meet the concerns of minority members. Indeed, his strongest backers were Max Goldblatt and the members representing the southern portion of the city.

Where Schrader found neighborhood groups to be rather irrelevant and scorned “social planners, ” Anderson has created a new “Department of Housing and Neighborhood Services” to tend to the needs of the city’s diverse residential areas.

Where Schrader managed to bring the city’s percentage of black managers up to only 6. 5 percent in nine years, Anderson has raised it to 10 percent in six months. The president of the city employees’ union says he has done nothing for lower-level minorities, but Anderson’s appointments are more than symbolic. Two blacks are now assistant city managers, and one, Levi Davis, is in charge of police and fire services.

The “delegation of authority” for which Anderson is praised by his employers on the council was necessary for him to achieve all those goals. He lacked the time to personally oversee so many changes at one time.

Anderson has given his administration a pyramid shape, with assistant city managers actually responsible for various areas of city government.

Evans says that some council members were concerned about appointing anyone who had worked under Schrader to the city manager’s position. They needn’t have worried. There are ample signs of Anderson’s independence from the Schrader heritage. He has obtained the council’s permission to reorganize city government, cutting out 10 departments and perhaps 150 of the city’s roughly 13, 000 jobs. He has rehired as an assistant city manager Jay Fountain, the former city auditor and “social planner” whose report on the property revaluation program so irritated Schrader. He essentially demoted Schra-der’s top aide, Don Cleveland, which may have hastened Cleveland’s decision to leave city government.

Anderson also has tried some ideas that his detractors regard as downright flaky. He put 35 top city employees on a special project to improve efficiency in city government -an idea whose results will not be known until this summer, when the group makes its official report. He defends the idea by noting that it is no more expensive than an outside consultant’s report and that staff members are more likely to follow their own recommendations than some outsider’s.

There is an element of unfairness to any comparison between Anderson in his initial months as manager and Schrader in his final year, but it is interesting to compare their reactions to their greatest public crises.

When news of the tax troubles broke out, Schrader denied that there was a serious problem. He denied it even to his bosses, who got several unpleasant surprises courtesy of the two Dallas newspapers. He failed to take quick action against any of the persons responsible.

When Anderson heard about the chaos in the City Equipment Services Department, he immediately started an investigation and determined that there was virtually no management control in the motor pool.

“We talked immediately when he heard about it, and we met that night, ” Evans recalls. “He said, ’It’s because of a lack of controls, and we need to make some changes. ’ And so we agreed and called the council and polled them and said we need to make an immediate change in the leadership of our equipment services department. “

Those changes were made, and by Anderson’s count roughly a dozen employees -at least one-third of them in some management capacity-were fired or demoted. When the acting director of the Equipment Services Department issued a gag order to his employees, Anderson countermanded it within 24 hours and asked all city employees to cooperate as best they could with media requests for public information.

But, of course, Schrader had a problem that Anderson, so far, does not. After eight or nine years in charge, his subordinates’ errors were his mistakes, too.

“1 think maybe when a manager’s been here for a number of years he may tend not to look at things as deeply as someone who’s new, ” says Haggar. “I think you get entrenched with your buddies over ten years and you become almost a captive rather than an administrator, ” says Gold-blatt. “You give a little here, you forgive a little there, and you make a mistake.”

Goldblatt sees one of the biggest dangers to Anderson’s regime coming not from the bureaucracy but from the council itself. In his effort to be impartial and agreeable to all members of the group, Anderson may be opening the door to improper interference by the council in the administrative side of city government, Goldblatt says.

“There’s a big danger that the council members are interfering in the day-to-day operations of the city quite a bit, ” he says. “It seems that more and more of the time they are trying to get in there and actually implement policies. The lead incident is one, where a member of the council insisted on having examinations of 12, 000 people. “

“I think that Chuck’s open personality maybe opens the door to some personal requests that maybe would not have happened under George Schrader’s regime, ” says Councilman Don Hicks. “I would hope that if any of us went to him with something like that, he would investigate certainly but not bow to the whim of a single councilman. “

Mayor Evans says he knows of council members who have tried to prevail upon Anderson in personnel matters. “I try to stop that whenever it comes to my attention, ” because it endangers the city’s entire system of government, he adds. He does not believe Anderson has shown favoritism to any clique on the council.

Anderson himself says that he has neither bent nor broken any city rules at the behest of a council member, but that whenever he gets a request for help he grants it, as long as it “can be accommodated within the city budget and the rules of the council. “

For a man whose job depends on making sure that at least two-thirds of an ever more divided group is on his side at all times, that seems like a reasonable precaution.

Related Articles

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert

Things to Do in Dallas

Things To Do in Dallas This Weekend

How to enjoy local arts, music, culture, food, fitness, and more all week long in Dallas.

By Bethany Erickson and Zoe Roberts