George Schepps was walking down Ervay toward the boulevard when a Baptist coach stopped him and said,”George, you’re the hardest thrower in South Dallas. Will you pitch for the church team?” What the man said was true and George, 13, knew it.

He hated to lose a game because he got a crick in his neck from looking up. He had been a bat boy for the Giants for two years; that was history. He could out-fight, out-cuss, and out-lie the worst of the Cotton Mill gang over on Corinth. The only time his big brother Julius ever out-ran him was when Julius, at 1:30 in the morning, stepped on a dead Mexican while throwing the Dallas News.

Before the coach turned to leave, he said, “You know, George, you’ll have to go to Sunday school.” The boy nodded. He ran to the Schepps Bakery two blocks away to ask his parents. They said okay because the pitching, after all, wouldn’t interfere with George’s Friday night bagelmaking in a back room of the bakery.

Sometime within the next few weeks, George’s throwing won the church team its first city championship. As the congregation at Ervay Street Baptist Church stood to applaud the little Jew boy, the coach said, “George, the most wonderful thing is going to happen next Sunday. Brother Matthew is going to baptize you.”

The smile on young George’s face was full as he burst through his front door. “You won,” said his father. “Yes,” said George, “but the most wonderful thing is going to happen next Sunday. Brother Matthew is going to baptize me.” His father, the baker, looked up. He took another puff on his cigar.

His mother Jennie, of coarse, immigrant stock, turned to her sweaty Jewish athlete and said, “Tell them to get another pitcher.” And they did. You always did whatever Jennie Schepps told you to do. Her three children called her “godmother” and her grandchildren later were to call her “czarina.” You were never invited to visit Jennie, you were summoned.

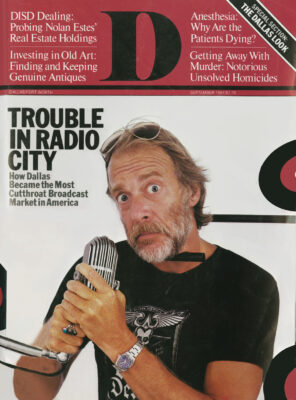

George is the third child. He’s 82. That’s not a twinkle in his eye. It’s pure lust. His brother Julius was the philanthropist; George is the swinger. He can talk for days about wine, good beer, whiskey, women, sex, and especially baseball. The nose, those far-reaching eyebrows, the pair of elongated ears manipulate every look. His hair is the color of a gleaming silver trout, and the tucks in his face are soft folds in a smooth-grained fabric. He’s aged well.

How does he stay so young? Well, he makes it a point never to associate with anyone over 30.

He won’t lift a case of Moosehead beer because he’s saving his back for more important things. “I can give up anything except … and I ain’t gonna give that up,” he says. “No kidding, I’m a great believer in that.” He gossips about his “athletic vasectomy,” an old high school football injury that left him sterile. He’s the type of man who has enough chutzpah to walk into an orphanage and adopt a baby without first asking his wife.

George is a sought-after speaker in Dallas circles. He’s a front man, the kind of guy who can really make you believe that what you are about to witness is the greatest show on earth. The best revelation ever is rosé wine, he says. The biggest mistake his father ever made was to turn down the rights to Dr Pepper. The biggest mistake George ever made was in not buying up all the land in Dallas when it was a dollar an acre. And the biggest mistake everyone else ever made was to think that Dr Pepper was made from prunes.

He has been a baker, owned an in-surance company, bought a brewery” coached a championship amateur girks’ basketball team, owned some ball clubs and run two bowling alleys. “I make everything a game,” he says. He probably wouldn’t have married his first wife Lily, had he not met some competition. ’

“Mother and I rode the train to Waco to see a I amity who also had a little bakery business. Their name was Cohen -is that Jewish? Their little girl and I became childhood sweethearts. What I didn’t know was that our parents had already set our wedding date. I didn’t see Lily for a long time. When I heard she was engaged to marry someone else, I married her. There was a difference of only 10 days in the wedding date our parents had set and the day we married.”

George could always get away with anything. He and Julius used to have seven of the Dallas News’ 24 paper routes. They hired three other boys to take routes and they kept four. One day George threw a paper through a subscriber’s front window. He looked down, saw a brick, and tossed it through the hole, too. Later the subscriber asked if he had thrown the brick. George said no. “Well, I’ll tell you what,” the man said. “Somebody broke my window, and you managed to throw that paper right through the hole.”

He also managed to steal cars, only he doesn’t call it that. He says it was “joy ridin’.” He’d swipe rich folks’ cars, drive them around for a while, then park them at the city park. He never got caught, partly because the firemen at Engine Company No. 6 across from his house swore he was playing dominoes with them all the time. It was George who taught firefighter Bill Latimer how to drive one of the station’s first automobiles.

While in the fifth grade, a teacher tried to rub the smile off George’s face with 63 switches during recess. She couldn’t do it. One little girl ran home to tell Jennie Schepps what was happening, but by the time Jennie grabbed her bullwhip and ran to school, the teacher had fled.

Jennie never used the whip on her children; her hand was always good enough. It was just as forceful.

“One day I talked Julius into getting on a freight train two blocks from our house instead of going to school,” says George. “We went to Waxahachie and got back just as school was out. Mother was standing at the edge of the driveway. She hit Julius with an open hand, and he went down. She put her foot on his neck and socked me and then whipped him.”

In the Twenties, Jennie opened a home for unwed mothers; her children read about it in the newspaper two years later. George asked why she hadn’t told them. She said, “It was none of your business.”

Joe Schepps, his father, died of cancer. He insisted he wasn’t ill, then one morning fell against the safe door at the bakery and came to rest in George’s arms. He died 11 days later in a hospital, but first told his family, “Now get out of here. I want to flirt with the nurses.”

Jennie died in 1946, also of cancer. She had hardly known a day when she hadn’t worked 20 hours. She outlived her husband by more than 20 years. She never really overcame the grief. The year before her death, she phoned the three children and told them to meet her at the corner of Young and Akard. “Bring your checkbooks,” she said. She was helped from the car by a small boy; she was on crutches because of hip problems.

“Do you see that building?” she asked the three. “I just bought it, and I want each of you to write me a check for a fourth of the cost.” The Community Chest, she explained, was scattered all over town and she wanted to put it all in one place: the building in front of them. Then she took the deed out of her purse and said they had bought it in memory of their father.

The building that houses the Julius Schepps Liquor Company sits on the same H&TC tracks that Joe Schepps rode into Dallas on in 1901. George’s office on Canton Street was once Joe’s bedroom, the site of Mrs. Bullman’s rooming house. If you trace the tracks, barely visible in spots, down Pearl to Elm, you wind up at what used to be the depot. It was here, at two o’clock in the morning on Valentine’s Day 1901, that Joe got off that train.

He was looking for a better life. He walked in the dark down Pearl, alone and broke with his wife and three babies on his mind. He had left them in St. Louis. Then he nearly fell over a figure seated in front of a darkened store. It was Ed Goodman, owner of the Model Bakery. “Why aren’t you working?” Joe asked. Goodman answered in German. His bakers hadwalked out. “I’m a baker,” said Joe, in German. He went to work.

The next morning he walked back to Elm. He saw storefronts with good Jewish names on them. “If other Jews can make a living here, I can too,” he thought. He was a determined man, with a hold on life solid enough to outwit Russian captors.

Zabaline, his birthplace, was a little town on the Polish-Russian border. Joe was a much abused child. In midwinter of 1888, the Russian army herded 18 of the town’s young Jewish men onto a train going to Siberia. They would freeze to death. In this group, and there had been many before it, were two bakers, Joe Schepps and his brother-in-law, Maurice Yuselovsky.

“The first night, all 18 tried to escape,” George says. “Several were shot. Some escaped through the underground to Germany. Only four, including Joe and Maurice, arrived at the same Jewish home. They stayed for several months.”

Joe had married Zlotte Yuselovsky, and finally, through the underground, she joined him in Germany. “They were able to make enough money to board a vessel that hauled freight and accepted only a few passengers to travel with the cattle and chickens,” George says. Three months later the ship docked at Ellis Island, a clearinghouse for immigrants in New York. There were no interpreters. Names were often changed for convenience and, more often, out of frustration. Officials had no trouble with Joe Schepps, but they couldn’t deal with Zlotte, which became Jennie, or Yuselovsky, which was changed to Nathanson.

“What is your father’s first name?” the interviewer had asked Maurice. “Nathan,” he said. “Well, since you are the son of Nathan, your American name will be Nathanson,” the man said.

In 1895, Joe and Jennie and their first child, Rebecca, moved to St. Louis. Julius and George were born there. Another child, Abe, was born between Julius and George. He died of pneumonia when he was two years old. Again, the Schepps ran a bakery.

“After we had been here several years, Dad told Mother he thought they should go into the matzo business. Manischewitz had the only matzos in America. They were baked in Cincinnati, and St. Louis was flooded with them. When Dad started selling his, the other matzos were seven and a quarter cents, so Dad sold his for the same price. The very next day, the competition went down to seven cents. A week later, it went to six and three quarters and Dad was meeting their prices. But when they got to five and a half cents, he and Mother closed up and Dad caught a freight train to Dallas.”

Robert (Bob) Thornton, the Dallas banker and later mayor, lent young Joe Schepps his first money. He told him, “Joe, if you can’t pay if off, I’ll take a team of horses.” Joe rented a two-room house at Hickory and Ervay, a few blocks from Mrs. Bullman’s house. The house faced an alley. Behind it were a barn and a corner building, part a meat market and part a bakery. Joe rented the bakery. He kept working for Ed Goodman, but bought Model Bakery products and sold them in his own retail store.

Jennie ran the store. Some say she was the brains behind the bakery. She worked out routes for George, Rebecca, and Julius. They took their horse-drawn trade from house to house, selling bread at five cents a loaf or six loaves for a quarter.

George was just 11 when he asked if he could have a little space in the store to set up a fountain. “I had saved up enough money to buy a soda fountain, and I was ready for business,” he says.

The biggest distraction, other than the Stuckey girl up the street, was the fire station across from the house. When the alarm at Engine Company No. 6 sounded, the Schepps brothers split out the door, no matter what was in the oven. Their father would say, “Boys, I wouldn’t do that if I were you.” But the only time he ever really told them “no” was when they wanted to enter politics.

“I was 22 and Julius was nearly 26,” George says. “We had a commission form of city government, a mayor and four commissioners. Their terms were expiring, and they wanted friends in office so they could still control things. They came out and visited with Julius and me at the bakery on a Friday and told us what they wanted.

“Being two egotistical guys, we thought, ’Well, with all the friends we’ve got, we can get elected and we’re gonna run.’ We asked for a week to consider it. A week went by and in walked the mayor and the four commissioners, going upstairs to the bakery. Dad happened to be standing there. He asked where they were all going, and when he found out what they wanted, he never let them upstairs. Instead, he called us down.

“He said his sons were not going to run for any office. He said, ’When you go into city hall, go into the men’s room and cleanse yourself. Do the same thing when you go to Austin and the same thing when you go to Washington. Cleanse yourself thoroughly, because when you mess with crap, you get it all over you.’ He told the men to get out of his place of business.”

The bakery continued to grow. The family bought the Kleber Bakery in town and renamed it the Schepps-Kleber Bakery. It turned out a variety of products: rye and pumpernickel, twisted egg bread, pan bread (which was a light bread non-Jews liked), and in 1915 they began making Butternut bread. George says he bought the area’s first bread sheer from the man who later sold him the Southwest’s first automatic pin-setting machine for his bowling alleys.

Joe and Jennie Schepps didn’t hoard their prosperity. They loaned money to other immigrants, especially the Greeks who owned most of the town’s restaurants. “Mother and Dad would go to them and say, ’Look, you’ve been here five or six years. You ought to bring your family over.’ ” The deals were called “salt water loans” because of the lengthy ocean voyage involved.

The Schepps brought over about 40 of their own clan, including many siblings. Joe located all of his brothers and sisters except one man, who was later thought to be living in Rio de Janeiro under the name of Rubenstei

Nathan Schepps, Joe’s brother, started the Schepps Dairy by following Joe on his bread routes. He drove a milk wagon and sold milk to Joe’s customers, especially the restaurant trade.

The only other move the bakery made was to the 2200 block of Ervay, next to a two-story house the family had built. The bakery was larger, and passersby could actually see the bread being made through a big picture window. Schepps bakeries opened in other cities. The Fort Worth plant was just being completed when the family sold out in 1929 to the Purity Baking Company.

The deal left the Schepps millionaires. It had taken a quarter of a century to amass the fortune. One day in 1929, their stock broker phoned. He said the market had just collapsed and they owed $220,000. The day after the news came, they began to pay off the debt. Both brothers got jobs with different insurance companies. Julius took a night class to learn how to sell insurance. The only thing George knew about the trade was that over the years he had accumulated $300,000 in life insurance; he didn’t exactly know why.

Their success was immediate. People who had bought the Schepps’ bread also bought their insurance. After 10 months, their mother insisted they open their own insurance agency. The Schepps, Sablosky & Peoples Insurance Agency prospered.

When prohibition ended, George sold his interest in the agency and built a brewery on Young Street. That was in 1934. Dallas didn’t have a brewery; all the beer was shipped in. George felt that if he could make bread out of yeast, he could also make beer out of it.

“I interviewed 15 to 20 very fine brewmasters,” he says. “I hired Oscar Kramer, a German. How this man loved his beer. I came back from a trip and my business manager said Kramer had just fired his brother, who had been hired with him. I asked Mr. Kramer why he had done that and he said, ’Schorche, we went up to lunch and he pulled a quart of Metzger’s milk out of his lunchpail.’ And I said, ’Well, what’s wrong with that?’ He said, ’If he’s gonna drink milk, let him go to work for your brother-in-law.”

The brewery sold about 100,000 barrels of beer a year to North Texans. The main label was a light beer, much before its time, called Schepps Xtra-Light. “I told Mr. Kramer we had a new generation, and that the beer brewed prior to prohibition was very bitter. I felt young people wanted a lighter tasting beer and that if we boiled our hops a shorter amount of time, we wouldn’t get the bitterness. I didn’t know that 1 was talking about, but Mr. Kramer said I was right.” Another Schepps label, Bluebonnet, was popular outside Dallas. The light beer, though, led the local market.

George owned most of the brewery stock, but the family had some. “Not much money changed hands in those days,” he says. They continued to run the brewery after George sold it to buy the ball club he had said he would own.

That was years ago.

Now George is community relations director at the Julius Schepps Liquor Company on Canton Street. George’s nephew, Phil Schepps, owns the firm, which Julius started in 1935.

Phil Schepps used to work for George at his brewery. One day George came to him and said, “Phil, I know your father might sometimes be hard to talk to. So I want you to feel like you can come to me if there is ever a need.” Phil had told his father “no” only once in his life; even then, his mother told him to do it. She wanted Phil to tell Julius to quit driving because he had run two red lights and a stop sign. “I nearly choked to death,” says Phil. “When I told him, he leaned back in his chair, smoked his cigar, and said, ’Well, can I choose my own driver?’ ” Julius chose a man Phil had fired five times.

The funny thing about Julius, who started the liquor business, is that he didn’t drink. He’d say, “Liquor is to sell and not to drink.” George thinks that’s a bunch of hooey. There’s a half-empty bottle of Early Times Bourbon in his desk drawer. He’s into a new drink, a gin and sonic, which a flight attendant introduced him to. “When she ordered a gin and sonic, 1 said, ’No, darlin’, you’re lisping. You mean a gin and tonic’ She said no, that you use the same amount of gin, but half soda and half tonic. The soda cuts the sweetness of the tonic. It’s a wonderful drink.”

One summer George invited a Catholic bishop to use his rambling White Rock Lake house for the summer. The house, behind H.L. Hunt’s place, had a bar along one wall. George didn’t want to offend the cleric, so he said, “Bishop, I’ll take this bar out, and this will make a fine place for your altar.” The guest turned and said, “Son, don’t you think there’s room for both?”

The liquor firm George works for has about 30 suppliers and serves the entire North Texas area; many of the lines are top sellers, like Seagrams, Bacardi, Chivas Regal, and Smirnoff. Foreign and domestic wines and beer are also stocked. George shows off the wares at wine tasting parties and beer busts. This is how he decides if a beer is good enough to buy, much less drink: “I take a pretty good mouthful and let it trickle down my throat. I’m looking for what I call a clean taste; that’s no aftertaste in the mouth proper. Just as soon as it hits the palate, my taste buds should taste nothing that’s resentful to me. I actually force myself to burp to see if 1 get an aftertaste. And if I don’t, well, that sho’ is fine beer.”

You would never catch Julius buying stocks the way George did. George would randomly stick a pin into 10 places on the stock page, then phone his broker to buy the stocks under the pinpoints. “I’d buy ’em, then sell ’em at $2.50 profit, and make $2500 that day. I didn’t know nothin’ about stocks.” When Julius gambled, he was cautious. George says, “Every year we went to the Kentucky Derby. I picked a winner four straight years. One year Julius said he wanted to sit by himself. When the race started, he jumped up and had a ticket on every finger and was hollering, ’Come on somebody. I’m gonna have a winner today.’ “

Julius would practice telling George’s stories, but it was never the same. Julius’ humor was intrinsic, not rehearsed. “He could tear people up with his humor, and it used to tickle me to death to watch him,” says Phil. “None of what he said was memorized. I used to watch him get up in front of 2000 people, with no notes, and just do beautifully. Getting up to speak just scared the hell out of me. When I went to national beverage conventions and had to speak, I’d get up and say, ’I’ll begin my presentation as soon as my father leaves the room.’ ” Years later Phil asked his mother Phyllis about Julius’ public speaking acumen, and she said that he had taken a Carnegie course without telling anyone.

Julius died May 15, 1971, of diabetes. He had made an indelible mark across the Dallas skyline. Once he worked at a bank for a close friend of his father’s. His employer said, “Julius, you are not a chip off the old block. You are merely a splinter.” That wasn’t true. Julius Schepps gave millions to Dallas. Any time an able helmsman was needed, Julius stood up. He offered community centers, parks, buildings, and friendships immune to social and economic prejudices.

Julius gave his time to the city in such proportion that Phil, his only surviving child, remembers having gone on a family trip with him only twice; he isn’t sure he was ever hugged. It isn’t coincidental that one of Phil’s bumper stickers says, “Have you hugged your kids today?” When Julius died, the Texas Legislature passed a resolution that calls him “Mr. Dallas,” and mentions the Israel Humanitarian Award of 1959 and the ways Julius Schepps “bettered” the city and the state.

The man rarely did anything halfway. A picture in George’s office shows Julius and his cronies holding a bunch of fish. The real catch is that Julius hated to fish; he had never held a hook. But since this was a fishing trip, he thought he’d better hold some fish up.

He loved to tell people he had gone to A&M for two years. Actually he had only attended 17 days: eight at the end of 1915 and nine at the beginning of 1916. The Aggie football team had walked out and Julius, being sympathetic, walked out with it. Julius was the type who could go to A&M for 17 days and then get elected president of the alumni association.

Most of the man’s metal and paper tokens of esteem and appreciation hang in a long hallway called the Julius Schepps Parkway at the Canton Street office. A freeway, renamed in his memory, nearly runs over the hall and becomes the road to Houston. Recently, says George, a coalition of blacks tried to change the name of this stretch to Martin Luther King Jr. A few well-placed phone calls took care of that.

The family called George “little brother.” He shows off Julius’ vast trappings in the Parkway like a dead hero’s curator. He was never jealous or even intimidated, though the Parkway is living proof of the man’s success. It is a wonder George’s own light hasn’t been eclipsed by the memory of such a magnanimous sibling. They were both extraordinary men.

George has been with the liquor company since 1974. Phil seems to enjoy having his uncle around. “There ain’t nobody equal to or better than Uncle George in what he does now,” he says. George’s cards used to read, “Director of Public Relations,” until someone at an early-morning breakfast said everyone is called that, and the title was changed to something more fitting. It really didn’t matter, though, because everyone still calls him Uncle George.

His office is the size of a second bathroom in a three-bedroom tract home. The building was flooded recently by a busted pipe and, though George’s office was untouched, it appears the worst hit. The disarray is out of sync with a man who sets his Omega seven minutes fast to avoid being late.

The gold watch is a gift from a woman who likes to buy him things. She found this one on a Caribbean cruise to St. Thomas. George won’t accept the trinkets unless she clears it with his wife. Evelyn Schepps, a former executive secretary who married George 17 years ago, doesn’t care about the gifts. It’s not that she’s so unencumbered by, well, by jealousy, but because she figures her octogenarian isn’t going anywhere, and if he does, he’s not going there very fast.

But does Mrs. Schepps know about the T-shirts, size “L,” in the back of the octogenarian’s beige Malibu Classic? The shirts, with “The Moose is Loose in Texas” on one side and some sort of slogan about Canada’s Moosehead beer on the other, are on their way to a wet T-shirt contest. The event is really a fund raiser for multiple sclerosis at a Dallas shopping mall; George is president of the local chapter.

The day after the benefit, he’s sitting at his desk and the phone rings. It’s one of the MS board members. “Did I see ’em?” says George. “I got pictures of ’em. Dou-ble-Ds. I tell ya they were double-Ds.”

When you’re with George, you get the feeling there are always famous people around. Pictures cover his walls. It’s intimidating. The one of Clark Gable says, “You have long ears. You’d do well here.” It was taken when George visited the Hollywood set with Lily, his first wife, somewhat of a theatrical person herself. She did Fannie Brice imitations so well that even Fannie Brice wondered about her. Sophie Tucker phoned George’s mother more than once to sing “My Yiddisha Mommy”; even Jennie Schepps was moved. Mary Pick ford crowned his grandmother on her birthday in a California rest home.

One scrapbook photograph shows George’s adopted son, George Schepps Jr., holding a football; he was about a year old. George saw him at The Edna Gladney Home when he was six months old. The boy’s looks were so close to George’s at that age that some wonder who the boy’s father really was.

The toddler grew into a man, six feet five, considerably taller than the Schepps men. He took flying lessons, and played baseball and football. His dad taught him about girls. He was 13 when George told him that if he ever took a girl on a picnic, he should take a blanket. “Then, when he was 16, I saw him walking out the door with a blanket over his arm,” says George. “I asked where he was going and he said, ’Dad, I’m going out and taking a blanket along because this girl is really going to be a picnic’ ” George Jr. was much younger when he learned of the adoption. His father likened him to Babe Ruth, saying the two were a lot alike because both had been adopted.

George’s son died when he was 35. He died of a heart attack while watching television one afternoon. He had married twice and had five children. George, a deeply emotional man, can’t talk about those growing-up years, or his mother Jennie, or his brother Julius without crying. All the Schepps, though, are like that. They cry just as comfortably as they laugh.

George has always been an athlete. He thinks he still holds the record of 63 chin-ups in elementary school. The trunkful of shiny agates he and Julius won is long gone, but the thrill of winning a city marble shooting contest isn’t. There were only two high schools at the time, Oak Cliff and Dallas High. The rivalry was intense. George says you didn’t play ball to win, you played to live.

“The 1916 Thanksgiving Day football game was coming up,” he says. “I went to Dallas High, but I met the most beautiful senior, Annie Mae Cook, at Oak Cliff. When I got to her house in my Model T, we decided to go to the Oak Cliff Pharmacy for an ice cream soda. That was a big mistake. We went into the drugstore and I saw about 20 Oak Cliff football players. The only available chairs were at the very back. As we sat down, the Leopards, as they were called, made their first play. They huddled around our table. The signal caller was a big tackle who was about six three and weighed 235 pounds. I was five ten and weighed 147. I think his name was Duncan. He looked at me and said, ’Jew, have you got any rabbit in you?’ I came out of my chair screaming, ’Yes. I’ve got some Irish in me, too.’ Fists started flying and I was told later that I hit everything in sight, including a lady shopper who just happened to be wearing the Oak Cliff colors.

“I started running down Jefferson. I ran for miles. Years later when the engineers started laying out the route of the first viaduct connecting Dallas to Oak Cliff, they said it wasn’t necessary to survey the route. All they had to do was follow the path of the Jew-Irish-Rabbit.”

George is president-emeritus of the Ex-Pro Baseball Players Association of Texas, and he was among the first to join the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. He and Julius began buying into baseball in the early Twenties. It was baseball that brought George Schepps and Amon Carter together. The two were enemies because George was for the Dallas team and Amon was for the Fort Worth Cats. One day Amon phoned and said he wanted to take George and 100 of his most loyal fans to the Dixie Series play-offs in Little Rock. There was to be a special train, he said.

“We were all standing there at the depot with our bags, and we heard the train whistle real loud coming into the station. Mr. Carter was standing on the cow catcher thumbing his nose at me as the train went straight on to Little Rock,” says George.

He was 10 when Dallas Giants manager Jimmy Maloney pulled him out of an oak tree near the ball park. “Wanna be a bat boy?” he said. Was there any doubt? George’s father wasn’t happy about the deal. He came out to the park one day and said, “Son, you’re out there working for nothing.” And George said, “That’s right. I love this game.” What Joe Schepps didn’t know was that when his son jumped out of that tree he vowed to buy the Dallas club someday.

In 1938 he paid Dallas clothier Sol Dreyfus $150,000 for the Dallas club of the Texas Baseball League. Whenever the team was on a winning streak, George asked his players not to change their socks and insisted that his wife, Lily, wear the same dress; she wore one polka-dot dress 12 straight days.

George renamed the club the Dallas Rebels. He got Jimmy Maloney to be his chief scout. His close friend Bob O’Donell became vice-president; O’Donell was an executive with Interstate Theatres. Hap Morse, who had played for the Steers, managed the team. What Morse wanted in return was George’s promise to eat Mexican food whenever the Rebels beat San Antonio. George ate Mexican food for 22 days.

“I brought a lot of happiness to a lot of people at my ball park,” he says. “It was a family park. I was one of the ones who started ladies’ night, where mama wouldn’t have to pay. I knew she wouldn’t come without papa, though. People thought that was pretty good business.”

One big thrill came in 1946, when the Rebels whipped the Atlanta Crackers in the Dixie Series. There’s a picture of the Dixie champs on George’s wall and another of the Rebels’ Al Vincent shaking hands with Atlanta’s Kiki Cuyler. Vincent is saying, “Kiki, George told us to knock you off in four. Just carried out orders.” George had always told his players if they lost a game not to look at him because he sure wasn’t going to look at them.

Julius went to most of the games. He was a better spectator than participant in most athletic contests. George says the only problem was he’d “express himself negatively.” The truth was, he’d jump up and shout tacky things at the players when they messed up. It upset George so much that after one game he had Julius handcuffed to his seat and left him there when the game ended.

George sold the Dallas club on opening day in 1948. He stood at home plate and said something nostalgic and then something about the offer being more “hay” than he’d seen in a long time. “I didn’t want to sell,” he says. “The money meant nothing. See, sports is my life.” Why, then, did he sell the club to Dick Burnett for $550,000? “Even a gentile couldn’t turn down a deal like that,” George says.

When Burnett died in 1957, the league asked George to take the team back. He didn’t buy the franchise, but he managed the team again. He renamed the Rebels the Rangers. “We went to Seguin for spring training and we had 106 warm bodies, most recommended by their fathers,” he says. “Most of them threw like girls. Of all my years in baseball, this was the most interesting.”

George made a fortune in baseball, but he lost it trying to rescue the sport from a preoccupied public. Dallas was only one of seven clubs he either owned or managed or both, located in Lubbock, Odessa, Greenville, Corpus Christi, Longview, and Montgomery, Alabama. It was the only minor league chain in the history of baseball, he says. “The media loved it because they abbreviated it S.I.C. for Schepps Independent Chain.” He brought athletes together, even went to Mass with some.

“I was the most stubborn minor league operator in the world. When they told me that television was going to hurt the attendance, when they said that 30 million people go boating every weekend, I didn’t believe them.

“I had four clubs in spring training at once. My father came out and saw 200 athletes running around, knowing we had paid for their expenses and put them up at the hotel. Jewish-like, I guess you would say, he said, ’Son, I don’t think you’re doing this right.’ And I said, ’Why?’ He said, ’It only takes nine people to play this game. Why are you feeding all those boys?’ “

George was known as the “savior” of minor league ball and later as “Mr. Baseball.” He doesn’t own a club now, but the glow of this sweetest love hasn’t waned. It’s the sort of radiance they say a woman has when she’s pregnant. Through the Ex-Pro Baseball group, George recruits young athletes for college scholarships. He seems genuinely ecstatic about that. In fact, he leads many of the baseball clinics at Arlington Stadium. “I tell those kids how I’m gonna teach ’em to slide into second . . . and I can,” he says.

The time seems right for stealing memories instead of bases. George is looking for a special place to keep the image of Jim Thorpe flying across the field at the 1932 Olympics to get Mildred “Babe” Didrik-son’s autograph. “George,” Thorpe said, “will you get me the autograph of the greatest athlete of all times?” The Babe shook as she signed his program, “To Jim Thorpe, The Greatest.” George Schepps, her friend, got chills just watching.

Last night George hopped out of bed at 2:30 a.m. and scribbled something on a piece of paper. He had dreamed that he had invited the Prince and Princess of Wales over for a benefit. Why not? Even George says he’s capable of selling anything. A cartoon in his office with the caricatures of Elizabeth Taylor, Barry Gold-water, and King Farouk says, “When it comes to promoting, you gotta go some to beat Dallas landmark George Schepps.” George says if he can’t raise a million in one evening, there’s something wrong with him.

He ran the Variety Club telethon in February and brought in $405,728 for charity. The multiple sclerosis chapter is $90,000 richer because George had a hand in putting on the May rodeo. “Honey, if you could see me in action, you would see that age means nothin’. If I’m huffin’ and puffin’, it’s because I’m blowin’ in a woman’s ear.” Jennie felt that if her children had her guts and their father’s personality, they would succeed in business. Jennie Schepps was a very smart woman.

Related Articles

D CEO Events

Get Tickets Now: D CEO’s 2024 Women’s Leadership Symposium “Redefining Ambition”

The symposium, which will take place on June 13, will tackle how ambition takes various forms and paths for women leaders. Tickets are on sale now.

By D CEO Staff

Basketball

Watch Out, People. The Wings Had a Great Draft.

Rookie Jacy Sheldon will D up on Caitlin Clark in the team's one preseason game in Arlington.

By Dorothy Gentry

Local News

Leading Off (4/18/24)

Your Thursday Leading Off is tardy to the party, thanks to some technical difficulties.