Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

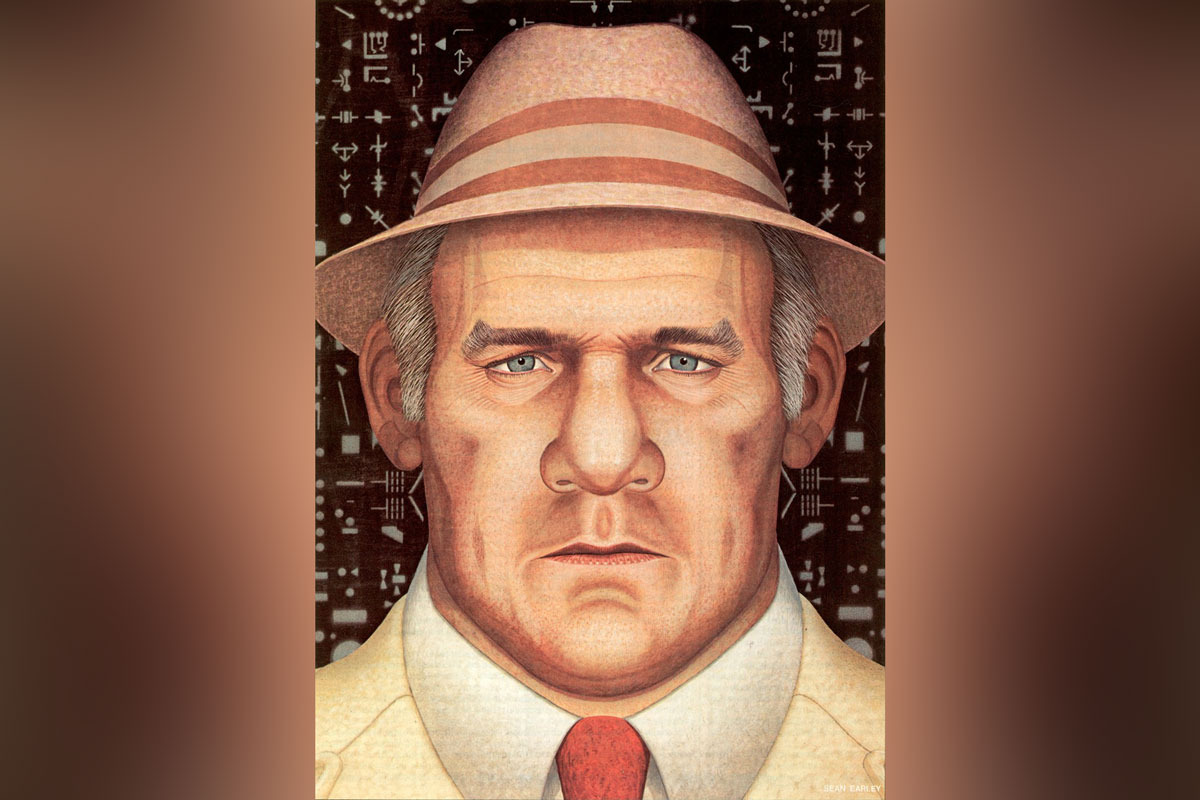

“The real danger is not that computers will begin to think like men, but that men will begin to think like computers.”

—Sidney J. Harris

Break the world in two. Smash life to bits. Yes/No. Right/Wrong. Them/Us.

At the Dallas Cowboys training camp this summer were two officers from West Point who were studying The Cowboys as the best type of organization for The Military. Battalion Command.

The military studies The Cowboy System because the military knows better than most. Management wins. Organization.

College football programs spit out players at an incredible rate and with little concern, but players are just the raw material and you can’t win without A System. A Consistent Management Philosophy. The Cowboys have been at it for 22 years with the same management team. Continuity.

• • •

After the Los Angeles Rams exhibition game this summer, I went down to the town square in Wimberley (near my home) and asked the boys on The Dinner Bell porch about Tom Landry.

Tom isn’t as popular with the boys on the square as Bum Phillips is. They can all identify more closely with Bum and have a new interest in New Orleans since Bum went with the Saints. But they all have respect for Tom Landry’s achievements as a football coach. The barber probably spoke for most of them when he said:

“Landry’ll do like he does every year. These exhibition games don’t mean nothin’.”

“Don’t be surprised if you see him in the Super Bowl,” the justice of the peace muttered.

The J.P.’s two oldest boys both thought the defensive secondary had serious problems and that the running fights with Drew Pearson, Randy White, Tony Hill, and Howard Schluser could be costly.

Everybody else was somewhere between those poles and had nothing else to say, except Dan and Mary.

Dan and Mary have thoroughbred horses and wanted pari-mutuel betting and horse racing in Texas. Tom Landry had taken a public position against it a few years ago. Pari-mutuel betting lost at the polls. Landry’s public pari-mutuel nosethumbing didn’t help at the polls.

“You mean to tell me,” Dan said quietly as he held his red, rough hands apart. (He was clutching his argument like a volleyball.) “That Landry don’t know how much betting goes on over football?” The horseman was asking himself.

“He’s a Baptist, ain’t he?” Mary said. “Ain’t he?”

“Methodist,” I replied.

“You mean he ain’t even a Baptist?” I nodded.

“Well, why the hell was he against it?” Mary was shocked.

“I don’t know,” I shrugged.

Other than the issue of pari-mutuel betting, we reached a quiet unanimity on The Dinner Bell porch. Landry had used the Ram game to look at what he had so he could prepare for the real season. Georgia Rosenbloom Frontiere (the LA owner), basking in the afterglow of the Raiders/LA Coliseum versus the NFL mistrial ruling, was intent on looking good on national television.

The Rams and Mrs. Rosenbloom Frontiere looked fine.

Do you think the Raiders should be allowed to move to Los Angeles? Do you think Mrs. Rosenbloom Frontiere is a natural blonde? Does Pete Rose really use Grecian Formula? Should Jack Kemp be allowed to make laws? Will SyberVision win $100 million from the Cowboys for alpha wave theft and sensory deprivation conversion by fraud? What is Tom Landry really like?

We will answer some of these questions. Some Yes. Some No. Definite maybe on one.

In trying to profile Landry, I must first admit my own prejudices and blind spots, although by definition they are probably inaccessable to me, only discernable in me by others. And in others by me.

First some background. Tom Landry was raised in Mission down in the Rio Grande Valley and starred in high school football. This brought him to the attention of D.X. Bible, the coach at the University of Texas. World War II interrupted his days at UT. Tom flew in B-17s in the European Theater. After the war, Tom finished school at UT and went to play professionally in the old All American Conference. The New York franchise. In the early ’50s, the league folded, and the New York franchise failed. The National Football League took in a couple of AAC teams (including the Cleveland Browns), and individual NFL teams picked up players. The New York Giants, owned by bookmaker Timothy Mara, took possession of Tom Landry; Tom would play five years finishing out as defensive back player/coach, then as full-time defensive coach under head coach Jim Lee Howell. Howell let Landry run the defense. Vince Lombardi ran the offense.

Tom worked on the 4-3 defense and created middle linebacker Sam Huff. Vince worked on the power sweep.

In 1960, Tom Landry was hired as the first head coach of the new Dallas Cowboys franchise. Vince was already in Green Bay.

The stage was set for my arrival.

I guess I was probably a trash football player. When I played basketball, we used to call them “junk” players. They didn’t look like basketball players, and they didn’t have the style or anything, but they scored — clumsily, sloppily, foolishly — and rebounded and picked up turnovers. Garbage collectors. They looked trashy, but they would beat you.

Did Bob Lilly and Ralph Neely really talk George Andrie into jumping out of the third-floor window of his Florida hotel room on a $5 bet and the promise that the roof of the poolside cabana would break his fall?

I was a basketball player that looked like a trashy football player. I couldn’t lift weights and wouldn’t have even tried to play football except that Gil Brandt was so persuasive in that East Lansing motel room (he refused to turn on the lights until I signed). I was real surprised once I saw the contract in the light. It said the Cowboys were in the NFL. I had thought they were in the AFL. That had been one of my reasons for signing. In 1964, the AFL was an expansion league. I could make it in the AFL. It seemed logical.

You won’t find guys like me with the Cowboys now. As Tom’s wife said recently, “Tommy finally has the kind of players he wants; all he has to do is coach.”

No personality problems.

(I doubt that I could make it through the Cowboys offseason training program now — much less make the team in training camp against Randy White and Harvey Martin.)

• • •

In late August 1964, the team flew in from Thousand Oaks. We had broken camp, but the final cuts weren’t made. Rookies stayed with Billy Mitchell at the Holiday Inn Central. On a good day, Dmitri Vail would roller-skate into the dining room.

After the final cuts were made, I drove down Central Expressway to look for an apartment. I went all the way to Richardson. There were miles of open fields between North Dallas and Richardson. I settled in at the University Gardens across Central from the old practice field on Yale Boulevard. The Cowboy Tower was just being built. The first generation of apartment dwellers was beginning to breed in the Oak Lawn/Love Field area. Dave Edwards’ apartment in the Four Seasons had a champagne fountain by his bed. I was making $11,000 in real pre-1968 dollars. Vietnam wasn’t hot yet, although it heated up fast. Only private clubs could sell liquor by the drink. Tommy Landry Jr. and Jodi Bailey were the ballboys. Angus Wynne Sr. and Jr. were still alive and Redford had yet to invest in Cabbage Cigarettes.

I bought a purple and white Mustang convertible from a Seventh Street Fort Worth car dealer who preferred old whiskey and young women. The car cost less than $3,000; with it the dealer sent over a knockout in a red Cadillac convertible with a matching tight sweater. I financed the Mustang for three years. Three K for white top and leather, and a specially built tape deck mounted behind the driver’s seat. Big Girls Don’t Cry by The Four Seasons was my first tape.

• • •

Needless to say, things have changed. Things were changing then, but only a few people knew it, and none of them told me. Nobody ever mentioned the word “Sunbelt” to me. Few people in Dallas knew of the Dallas Cowboys Football Club, Inc. Fewer still went to the games. I wouldn’t have gone except they paid me. I’m glad I went. I got to see legends being born.

A lot of water has gone under the bridge since the days when Bob Fry taught offensive holding, and Don Meredith got broken up just trying to throw a quick down and in. Don Perkins ran second only to Jimmy Brown, despite his broken foot and our muddled but lovable offensive line. And Amos Marsh never took a shower that I witnessed or heard about.

Tom Landry got to see it all. Twenty-two years. What did he see? What was he looking for? And who sent Bob Hayes in for Frank Clarke on the goal line against Green Bay in the final seconds of the championship game after the 1966 season? Or did I just imagine that?

Did Don Talbert, Bob Lilly, and Ralph Neely really talk George Andrie into jumping out of his third floor Bal Harbor, Florida, hotel room window on a $5 bet and the promise that the roof of the poolside cabana would break his fall? And did the three really refuse to pay George his $5 after Bullwinkle lept out the window and crashed through the cabana, landing on a table and injuring his ankle? All I know is that the four of them rented a white Cadillac convertible and kept the trunk filled with beer for the whole week before the post-1965 season Playoff Bowl.

I went deep-sea fishing with them in the middle of the week. After practice, we bought warm beer and two tubs of Colonel Sander’s Kentucky Fried Chicken and drove the Caddy out of Bal Harbor north toward the charter docks at The Castaways. We ate cold, greasy chicken and drank warm beer all the way. Heading out in the boat, we fed the constantly hovering sea gulls a mixture of dead cut bait and live cherry bombs. It would have given Richard Bach cold chills. It seemed quite funny at the time. It still seems funny. Later all of us got seasick, which wasn’t at all funny. Seasickness seems funnier now.

There were Giants walking the Earth in those days.

• • •

“We are all crashing to our death from the top story of our birth to the flat stone of the churchyard and wondering…at the patterns on the passing wall.”

—Vladimir Nabokov

Through everything I harbored a deep and certain physical respect for Tom Landry. He was a leather-tough, hard-hitting — maybe even late-hitting — passion-driven player. As a football coach, he always maintained his physical condition. Football is a collision sport (dancing is a contact sport), which is part of every player’s and coach’s psycho-structure. You hit people to solve problems. Often.

In the corporate structure of The Dallas Cowboys Football Club, Inc., a subsidiary of Clint Murchison’s Tecon Corporation (a holding company), Tom Landry is what is called a “Gamesman” by Michael Maccaby in The Gamesman: The New Corporate Leaders. Team President Texas E. Schramm would be described as a “Jungle fighter,” a go-for-the-jugular type.

The Jungle fighter’s goal is power; and life is a jungle, not a game.

The Gamesman’s goal is winning. Tom sees life as a game, not a jungle. A deep concern with tactics and strategy makes up a large portion of his character. It is all a game that is won or lost. Over and over.

Years ago, Landry told me his philosophy. It is remarkably consistent with the passage of time:

“I think the idea is to stay up close to the top with your organization and hope every once in a while you pop it. In our game you’ve got one goal: the Super Bowl. I mean, that’s all you’ve got in our business today — you win the Super Bowl, how can you get back again? It depends a lot on the age of your club, your people. The older you get, when you accomplish a goal, the more you look outside of football for what’s gonna happen in a year or two…

“I think mental attitude has a lot to do with injuries. I think if your mental attitude is not right, you tend to have more injuries.”

This is also called “Blame the victim.” It’s good if you have to testify in court.

“I do a lot of work in the religious area, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and all this type of thing. That’s my main activity other than football, but it doesn’t distract me. I’m a football coach, and I’ll be a football coach, you know, as long as somebody will let me coach … I can still have incentive, but I think your whole organization suffers a little bit from accomplishment.”

Sounds a little like a double bind.

“You have to pay a tremendous price of dedication, discipline, and all the things that go into a championship team, and once you’ve made it, you like to rest a little bit; it’s human nature…”

It’s a double bind all right.

“Well, you lose the winning edge … it’s so minute, so small the difference in winning and finishing also-ran. It’s so small most people can’t see it … Even the players won’t recognize it.”

I was afraid of that.

I asked Tom if he found any contradiction in being a professional coach and a born-again Christian.

“The thing that concerns me most, Pete, is that I’m handling everyone with fairness. We have a certain thing that we have to do in football to be successful … If I’m not willing to do it, then I don’t belong in the game … I feel bad if I can’t deal in fairness with people, and I try always to deal in fairness with them to let them know what is expected of them and if they don’t measure up, the consequences that are gonna happen. If I can do that with them, then I’m not affected by it as much.”

You can’t say he doesn’t want to be fair.

“I think there has to be a separation between my position and the rest of the team. By nature, I would love to be different. I enjoy people … I’d like to be out on the field with these guys just helping them to develop and have a close personal relationship with them, but I can’t do that as a head coach. My responsibility is to do what’s right for the team, and when you do that you’re gonna hurt individuals. That’s the requirement of being a head coach … anybody with responsibility, if you run this corporation, if you run the country. If you’ve got enough responsibility, you’ll take the cold aspect every time.”

He makes responsibility sound like a drag.

“Football players are exceptional people in that they have the opportunity to overcome defeat and many people cannot overcome defeat…”

That’s one reason they call it defeat.

“When they are defeated, they tend to have to turn to things to support them … alcohol, drugs. They’ve just never quite learned to completely overcome defeat.”

Did anybody mention the opium of the masses?

• • •

“When I took the job in 1960, I wasn’t worried in the least, mainly because I didn’t plan to stay in football. I had earned a business degree at Texas and had just added a degree in industrial engineering at Houston. I felt it was just a matter of time before I found a good job.”

—Tom Landry, Sporting News, 8/15/81

The sun got in Tom Landry’s eyes. He tripped over a rock and stayed 22 years.

And now, by virtue of his efforts and The Fates, he is an American Hero, a cultural hero who is the object of millions of fantasies. The Fates stepped in and developed the telecommunications technology to provide huge audiences at the same time Landry was developing a football technology that was to mold The Dallas Cowboys Football Club, Inc., into America’s Team.

The television technology and antitrust exemptions produced a National Football League network, and millions of uncommitted fans were treated to the spectacle of Tom Landry, Tex Schramm, and Gil Brandt building a professional football franchise from the ground up for the fun and profit of Clint Murchison Jr. Tom Landry’s public profile could bear the scrutiny of hero worshipers. Tom Landry became “the legendary head coach of the Dallas Cowboys.”

Legends, of course, are larger than life. They don’t demonstrate the failings of lesser mortals. They don’t show emotion. In his business, Tom Landry believes that emotional distance is a necessity.

Tom is not unemotional. I’ve seen him take a fit in public; not often, but it happens. You see it when you know the Cowboy System and know what to watch and when and where. Tom Landry is an emotional man, but he has it disciplined and detached.

The production of Super Bowl champion-caliber teams takes tremendous dedication to a state of mind. Adversity must be overcome (and if adversity isn’t there, sometimes it is necessary to create it). Tom has overcome his adversaries in football more often than not. Losing is the testing in fire. Tom knows it well. Winner or loser, Tom survived the fire. Now he controls it. He maintains a dialogue with God, but seems to look at his players in terms of the execution of various technical functions of professional football.

What is Tom Landry really like?

I get asked that about as often as I get asked what Don Meredith is really like, which is a lot. Near the end of his career in 1969, Don seemed to like Tom more than Don liked Don. I liked them both for a while, but then they made me mad, and I didn’t like them for a while. And then, of course, it finally reached the point where I just didn’t give a shit. Who really cares in the first place?

Generally, the relationship between coach and player has a certain adversary aspect. The athlete is supposed to challenge himself constantly. The coach monitors this self-challenge and often provides extra incentive when he thinks the athlete is not pushing himself hard enough. My adversary relationship with Landry was a lot like trying to hit a silk handkerchief. It is not you, it is your technique that Tom is interested in. Nothing personal.

Yes, Tom is emotional, but he directs his anger at poor execution. Technique. Tom is quite emotional about technique. He is a great technician. He is even adaptable.

In 1964, anyone caught in the alpha state (total mental relaxation) was fined. It was in the playbook fine schedule: Making Alpha Waves —$25 for every minute the player is blissed out. There was a sign in the training room: DON’T MAKE ALPHA WAVES. But today, ol’ adaptable Tom’s got players in isolation tanks going for alpha on purpose.

It is said that messing with a body’s alpha waves can lead to as yet unknown dangers. I believe it. I don’t let anybody touch my alpha waves, let alone borrow them.

• • •

In 1964, Tom Landry was the head coach of a losing system, an expansion team in the mighty NFL. The team played in the Cotton Bowl. Eddie LeBaron had retired and left the quarterback job to Don Meredith. Crowds seldom exceeded 25,000 to 30,000, most of them in the cheap end-zone seats.

Lamar Hunt had taken his AFL team out of Dallas to Kansas City. It has often been alleged that a secret agreement existed between Hunt and Murchison, allowing Hunt to buy into the Cowboys franchise should his Kansas City franchise fail. Obviously neither failed, but in 1964 the Dallas Cowboys were hardly a household word. I have a 1964 Cowboys schedule that shows Dandy Don running in that silly-ass old blue and white uniform with the stars on the shoulders. The team logo was still that little fat cowboy horse. Tickets were $5.50 at the top end and $1 at the low end. Kids got free footballs, and five kids under 12 were admitted free for every special general admission ticket.

Twenty-five thousand to 35,000 people at a game. Tops.

The Dallas Cowboys were not well known even in Dallas — let alone Texas or the whole planet, which now seems to be the case.

In 1964, I got to play maybe three or four plays, not counting special teams. I might have gotten to play more in 1964. Green Bay was beating us something like 41 to 21 (our defense having scored 14 of the 21, including a touchdown scored after Paul Hornung, Warren Livingston, Jim Taylor, and Cornell Green fumbled a ball back and forth the length of the field from about our 15 to the Green Bay end zone).

It was during that Green Bay game that Tom called me to his side and told me to get ready to go in for Buddy Dial. It was to be my first game action from scrimmage.

I inquired if Tom thought it was safe for me to go out there.

He didn’t say anything, but gave me a funny look.

I got to play two or three plays, and it certainly didn’t seem very safe. John Roach was working at quarterback. John didn’t think it was all that safe either.

Once in early 1967, I caught a low pass across the middle from Meredith against the Giants. I just lay there after the catch. I had found running to be futile in football. It was also dangerous. According to the rules, all Vince Costello (the New York middle linebacker) had to do was to touch me and I would be whistled down. I lay there waiting for the tag.

Instead, Costello took a running jump and buried a knee in my back, breaking off some short ribs and playing general havoc with the nerves and muscles of my left lower side. My left leg went dead, and my right leg burned like fire. They dragged me to the sidelines and then to the hospital.

We won the game.

Afterward, several players showed up at the hospital to visit and celebrate. The night nurse ran them out when she came with my Demerol. The nurse cussed and filled the wastebasket with empty beer cans and whiskey bottles. She used the wastebasket to prop the door open.

The night passed in a fog. Shots every four hours. I felt no pain. I felt nothing.

The next morning at daylight, the door pushed open slightly and through the narcotic haze I could see Tom’s face.

I opened my eyes wide and tried to sit up. Tom stepped into the room and kicked the wastebasket over, spilling out empty whiskey and beer bottles and cans. They skittered, rattling and crashing across the floor. Tom just looked at me, sort of funny, like he did when I asked him if he thought it was safe to go into the Packer game.

• • •

Tom Landry seldom failed. He has suffered defeat on a human scale, but he doesn’t seem to have failed. He survived World War II as a hero who walked away from B-17 crashes and flew 30-plus missions over Europe, including some extra volunteer missions for his brother Robert, who died in a crash in Iceland.

Once, as the B-17 engines died returning from a bomb run, the crew began organizing bail-out when 20-year-old Tom Landry thought maybe the fuel mixture might be wrong. He returned to the cockpit, fooled with the mixture, and restarted the engines. He restarted the engines.

You won’t find guys like Pete Gent playing for the Cowboys anymore. As Alicia Landry puts it, “Tom finally has the kind of players he really wants; all he has to do is coach.” No personality problems.

Back in 1965, we had lost five out of the first seven games, and the rumors were thick and furious. Everybody said that Landry was through and Meredith was through and the IRS was insisting that Murchison had to start showing a profit or have the Cowboys declared a hobby and lose all his tax advantages.

On team flights, some players began to wonder about the team insurance. We flew propeller-driven Electras then, seven hours to New York. We breathed easier when Clint, Tex, and Tom were aboard.

In the midst of this chaos, Murchison said that Landry had a new 10-year contract. Landry said that Meredith was his starting quarterback. The Cowboys won the next five out of seven games to end up second in the Eastern Division and faced Baltimore in the ignoble Playoff Bowl. Seven and seven in 1965. It seems almost as fantastic as the IRS declaring the Cowboys a hobby. The Cowboys would never know another losing season.

Management wins championships. “The secret to winning is constant management, and that quality comes down from the owner,” Tom told the Sporting News recently.

Constancy. I have never noticed much difference in the Cowboy teams that Landry has fielded since the late ’60s. The great players have come and gone, the System has remained. The System has won.

The Cowboys, better than any team I know in the National Football League, have been able to maintain the illusion, as well as a certain amount of fact, of the separation of powers between Tom Landry as head coach and Tex Schramm as management.

Tex Schramm is no lightweight.

The players virtually have no idea who is dealing with whom or why or what is being said and planned. In the newspapers of August 10, there is this picture of a fat guy protesting the baseball strike by burning Mickey Mantle’s bubble-gum card valued at $1,300. The crazed fat man burned $64,000 worth of other cards to protest the recently ended baseball strike.

What a fool. At least Tom would think the fat fan was foolish. Tex would encourage the fat guy, then use it as a negotiating lever. The difference between a Gamesman and a Jungle fighter.

• • •

“I know an old lady who swallowed a fly.

I don’t know why she swallowed that fly.

I guess she’ll die.”

—’50s hit song

A few years ago, I was in Dallas and went to a party for Buddy Dial, one of my fellow wide receivers. Buddy is suffering from kidney failure, a complication of narcotic use pursuant to his breaking ribs and losing his starting job to me, which I subsequently lost to Lance Rentzel. At the party, we prayed for Buddy’s kidneys, and Buddy told me how he used to steal my codeine pills while I was out on the field. Buddy lost his wife. The last I heard, he was living with his son. A few months ago the boy called here looking for Buddy, saying that Buddy had left Houston heading for my place in the hills. Buddy never arrived.

Ed Garvey, executive director of the NFL Players Association, told me the retirement board recently gave Buddy full disability.

“He’s dying, you know,” Garvey said.

Yep. I knew. Don’t know why. Guess he’ll die.

Buddy said that nobody ever told him he had broken his ribs. You can’t trust them old drug addicts, though. Right?

I knew an old lady who swallowed a horse. She’s dead, of course.

• • •

Now Tom has installed sensory deprivation tanks at the Cowboy practice field. He thinks the alpha state achieved while floating in body-temperature saltwater in the soundless dark will enhance the learning process of his players.

Things have certainly changed. I guess Tom has loosened up a bit.

I imagine they’ll pick a few of the boys down out of the trees before they get the bugs out of the isolation tank experiments. Not to mention the $100 million lawsuit SyberVision has filed against the Cowboys. It just seems to me that in a business based on violence and repression and controlled aggression, the alpha state is one of those little closets in the mind that are best left locked up.

“Player coach … player coach,” I believe is what John Niland called from the treetops when he hit alpha. He called it a religious experience, and who am I to argue? I prayed for Buddy Dial’s kidneys.

Once people get to mainlining alpha state and adrenaline, the question becomes whether it is a closed circular system or a descending spiral.

• • •

“He was proud of Pettis and often related in speeches how his tight end had shown the fortitude, drive, and character to work his way up from very humble beginnings to gain a college degree and then become a vice-president of a bank in Dallas. Pettis, thought Landry, certainly was an inspiration during times when young people needed someone positive with whom to relate.”

—Bob St. John, The Man Inside … Landry

A famous man was asked what he thought history would record about his life.

“Sir,” the famous man replied, “history will lie.”

In editing St. John’s book about Landry, Word Publishers took out any mention of Tom’s drinking (he was a martini drinker in New York and was once semi-famously drunk in Toots Shor’s). Word Publishers cut it out, calling it “negativity.”

Word Records produced Buddy Dial’s album in 1964. It was called “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” Buddy was in uniform on the cover.

Pettis Norman, the man Tom Landry used to point to as an example of the American Way to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, is no longer invited to the Cowboy reunions, an event he helped originate. Pettis filed suit against the Cowboys because he said they kept certain facts about the degenerative condition of his knees from him. Pettis is looking forward to years of pain and finally joint replacement.

Tex says Pettis can’t come to the reunions anymore because he “impugned the integrity of the Cowboys.” I wonder what Tom thinks?

No longer is Petty the Cowboy example of the good boy. They even let the good boys wear mink coats now.

They say Tom has loosened up. I guess so. He owns part of the club and makes $250,000 a year to be a Hero. It’s a great job, and he’s worked hard for it. He has sacrificed. He has paid the price. He has detached himself from the men who play for him. Born again. Detached.

Is anybody home?

Tom Landry’s practices are organized and accomplished specific goals; little time or energy is wasted. He is the technician. Skillful. Enjoys solving problems. Wins. Tom cares about football. He is really good at breaking it into its components. An engineering degree and a religious dedication.

And The System: Nowhere in the NFL do you have the record of continuity that you have in Dallas. The players are now negotiating with the guy who used to be ballboy.

The football team will be there forever, like the river, but the players will change, like the water. Drew Pearson? Randy White? Bob Hayes? Bob Lilly? Dandy Don and Roger Who? Does Tom think his players are being exploited and misadvised about their physical and emotional and financial well-being? He is most certainly not to know. That is negativity. He stays detached, purposely blind.

Tom Landry is a Gamesman, and football is a game, The Game. He never considers the value of the rules or the effect of the game. He deals in strategy and tactics, not values. The game is good, by definition.

In 1973, I asked Tom if he thought there was much drug usage among the Cowboys. Tom said he hadn’t noticed. I wondered what he thought the trainers and the training room and the team doctors are all about. Tom focuses his attention. He concentrates, and he sees what he chooses.

Here is where it ail starts to be spooky. Now Tom is taking his position as a cultural hero seriously and using the immense powers that come with being a hero.

Does Tom notice the immense social impact that football has on the tenuous fabric of American culture in the ’80s?

I don’t think it is overstating the case to say that professional football and television have created some serious aggression reinforcing types of role models from player to coach to general manager to owner.

• • •

“The Germans were the greatest of military minds” said Landry, who includes World War II among his reading. “They had so many of the geniuses during the war — but the Allies, the people in the United States were just supremely determined.”

—Bob St. John

(Nobody dropped any bombs on Detroit, Chicago, or New York either. They say imminent death has a way of focusing one’s attention.)

“All morality is ultimately a quest for power,” one of those unhappy brooding Germans said a long time ago. And all power is ultimately a quest for immorality.

A Thousand-Year Reich. A Dynasty.

Winners and Losers. Good and Bad. The World broken in two.

Opposites. Them/Us.

• • •

The last time I saw Tom and Alicia Landry was at the team reunion in 1977. I wrangled myself an invitation by writing Tex and asking for one. I based my plea on fairness.

The whole weekend was a long drunken anxiety attack. It was the year they put Chuck Howley in the Ring of Honor, I think. Willie Townes had promised to bodyguard me, but I got drunk and told Rayfield Wright he was uglier than I remembered. Rayfield just smiled and squeezed my head until my nose bled.

At the party I found myself standing next to Alicia; shortly, Tom was standing there also. Alicia was still lovely. Tom looked older — less hair, but he radiated strength and good humor. He was quite pleasant to me. Detached, but pleasant.

I was no longer a part of The Game.

If war is the ritual for the emergence of cultural heroes and the ground on which to show that the gods, any gods, favor you; and if football is a ritual substitute for war providing all the social cohesion of a “good war” (one you win) as opposed to a “bad war” (one you lose), we can see why Howard Cosell can say on Monday Night Football that the Browns Football Club, Inc., is “good for Cleveland” and not consider himself an idiot.

Are the Cowboys good for Dallas?

Well they aren’t really in Dallas. Besides, they are now being called America’s Team.

Are the Cowboys good for America?

Is America good for the Cowboys? The Gipper is president, and Jack Kemp is making tax law. Tom Landry would probably stand a good chance of being elected to any statewide office. The U.S. could audible the shit out of the world.

Get the ItList Newsletter

Author