My story is not unlike that of many women in my generation. We thought our lives had to be decided at age 20. We looked forward to a bleak and lonely future if we weren’t engaged by then. At the University of Texas, girls found the man they were going to marry in their junior year. In your freshman year you dated everyone you could possibly meet. During the sophomore year you went with a couple of them until you found the right one. And by the time you were a junior, well … But by the time I was a junior there was just nobody special in my life, and I was afraid I was going to graduate and be alone and not have a man. After all, I wasn’t getting a degree to have a career, I was getting a degree to stand behind somebody. And it didn’t look like there was anybody who needed me behind them.”

In 1962, her junior year, she started dating her high school sweetheart again. Today she calls him a liar and an adulterer. Back then, she saw him as the gateway to her real life.

“I come from a time period when you didn’t experiment sexually, and everything was postponed until after marriage,” she says. “Everything. Career fulfillment, everything. So in order to get on with my life, I had to have a husband. Had it been today, maybe we would have been smarter and done what the kids are doing -maybe lived together -and that would have prevented the marriage.”

Today Betty is living out the consequences of the step she took 20 years ago. She knows she never should have married Mike. But she did. Now she’s pushing 40, and she’s alone.

She’s divorced.

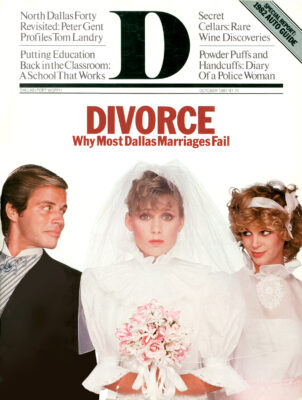

THAT CIRCUMSTANCE makes her something of a tragic figure to people of her parents’ generation. But by the standards of Betty’s own generation, it makes her something else: normal. Divorce in America has become the new normality. The children of the postwar baby boom, the age group that dominates society in terms of influence and in terms of sheer numbers, have grown up. They’ve married. And had children. And, more often than not, they’ve divorced.

Divorce is no longer a societal anomaly. It is the new social norm. The average marriage today will fail. It will last, statistically, 7.6 years.

Dallas, for reasons we know and reasons we don’t know, has become the divorce capital of America. Dallas leads the nation’s 15 largest cities in per capita divorces, with almost twice as high a rate as New York, Chicago, or Philadelphia.

The toll of “broken” marriages seems to mount daily. Between 1970 and 1980, Dallas County’s divorce rate jumped 13.5 per cent, to 85 divorces for each 10,000 residents. 13,219 divorces were filed in the Old Red Courthouse last year. Tarrant County logged only 7756 divorces in 1980, but its divorce rate soared to 90 divorces per 10,000 residents last year, a 31.15 per cent increase over 1970. For the past decade, Dallas County court clerks have watched the number of divorces gain on the number of marriage licenses issued in a year. As of mid-August, divorces were ahead, 13,642 petitions to 12,477 marriage licenses.

Dallas’ divorce rate is so high for two reasons: because its residents are like people all over the country, and because they are different.

Nationwide, the divorce rate jumped 51 per cent between 1970 and 1979. When a government statistician asked his computer what was happening with American families, the machine replied that families are increasingly prone to self-destruct. Marriages formed in 1950 have a 70.5 per cent chance of survival. The mortality rate increases steadily for each succeeding year, and by 1973 brides and grooms were facing a theoretical survival rate of only 51.8 per cent. “I think that if those projections were done with current data, the divorce rate would exceed 50 per cent,” says Jim Weed, chief of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Marriage and Family Statistics Branch.

In some ways, it is easier to get divorced in Texas than it is to marry. New York State still requires a one-year wait before a couple can get divorced based on incompatibility; Texas allows divorces to become final two months after they are filed.

Dallas also has a younger population than the nation as a whole, which contributes further to the divorce rate.

Perhaps more important is the type of young person that Dallas attracts, and the fact that so many residents of this area have migrated from other parts of the country. Marriages may become more frail as couples leave behind the families and friends who helped cement their ties and values, Weed says. And the sort of person who would travel thousands of miles to a strange city may be more independent-and therefore more divorce-prone-than the friends and relatives he left behind.

Attorney Charles Robertson can name three complaints that explain most of the 150-odd divorce requests that he may handle during a year. “Either they’ve stopped talking to each other or it’s sexual relations or it’s money,” he says. “It’s not so much poverty -when you don’t have much money, everyone is on edge -but most of the time one partner does not want the other partner to have any say in how the money is spent, or be accountable for it. And, especially with the women, we have some of the ’what’s mine is mine, what’s yours is mine’ syndrome.”

“We had a television newswoman who earned $35,000 a year, the same as her husband, and her feeling was that everything she made was hers, and everything he made was for the family,” one local attorney says.

DALLAS MARRIAGE counselor Gay Jurgens takes a deeper perspective on the three principal reasons for the breakups of most marriages: A lack or overabundance of expressiveness (“He never listens to what I say,” or “She’s not interested in what I do”) is one. A lack of psychological and physical closeness (“He never wants to make love,” or “I want to take a vacation alone”) is another. The third is power: whether it be power to set a family budget or power to decide where Johnny goes to school or what the family eats.

In the good old days, power struggles among couples were often guerrilla wars. The man held the main highways and cities – checkbooks, credit cards, and paychecks-while the woman slashed at vulnerable points along the periphery-employing extra starch on the collar, absentminded “unauthorized” purchases, and late-night headaches.

Nowadays, Jurgens believes, women are more likely to be assertive, “perhaps aggressive.” She likens the situation to a movie theater where a person’s back-seat neighbor keeps kicking his chair: The sooner something is said, the less violent the eventual reaction. But Jurgens worries that the I-me-my generation may be setting itself up for a fall regarding marital power.

“The new program, unfortunately, is that everything has to be equal, and equality translates into 50-50 in each area,” Jurgens says. As anyone who has ever cochaired or coauthored anything can testify, that mathematically perfect formula just won’t work.

The healthiest families are those in which power is shared by the parents, but is not based on any rigid formulas, psychologists contend. The husband may keep the books one month, the wife another. The wife may decide where to vacation, leaving the husband free to spend some of the family’s “discretionary” income on a favored hobby. (Think of Mrs. Smith going to Acapulco for cash plus a future draft choice.)

Gay Jurgens has research findings to support her descriptions. Dallas’ own Timberlawn Foundation, Inc., has sponsored the nation’s most detailed study of “Healthy Families.” The families were picked from among the congregation at Highland Park United Methodist Church. All had teenagers, none showed signs of psychological stress or craziness. The healthy families had much in common, besides money (similar studies of poor, black families expecting their first child, and single-parent families are underway).

Either parent could make decisions in the healthy families, and each parent respected the expertise of the other, according to Dr. J .M. Lewis, director of research at the foundation. “Family problem-solving was characterized by negotiation. They formed opinions, they listened to each other, they were good at working out compromises, but it was clear in the final analysis that the parents were in charge of the family,” Lewis says.

The families tended to be warm and friendly, optimistic about the future, and comfortable enough with the present to maintain strong senses of humor. Parents and children alike were encouraged to express themselves, “and if someone was feeling something, there was a high likelihood that someone else in the family would let them know that they understood,” Lewis says.

Despite all that closeness, “the families also encouraged autonomy and respected the fact that people are different,” Lewis says. Boys did not have to play football; girls did not have to be shy and retiring. “The kids were all given some responsibility for their own lives, and all were doing well,” he says.

Dr. Bruce Pringle, a sociology professor at SMU, says that the researchers stumbled across another finding: Psychologists do not come from healthy families.

Jurgens, who is divorced herself, finds that her clients’ family lives are wounded or dead by the time the couple comes through her office door. She says “the couple” because she does not treat marital problems unless both husband and wife are attending the sessions; one cannot accomplish much by treating half a relationship. With 12 weeks or more of joint treatment -costing $550 or so-however, Jurgens has been remarkably effective.

By the time most of her clients have sought her help, they’ve already considered divorce. Their marriages are battlefield casualties -chest wounds and severed arteries. They don’t talk at breakfast. They don’t talk in bed. They don’t do much else in bed, either. “The first thing I do is to try to get them to care more for each other, whether they want to or not, and to take meticulous notes of things that the other spouse could do to make them feel good,” Jurgens says.

It’s really sort of grade-schoolish. Husband and wife write down things their mates could do to make them feel more cared for. “Make me a candlelight dinner, from scratch.” Or “Take me on a trip.” Or, Jurgens says, “All those things they did when they were in love, but have stopped doing.” After writing their own lists, the husband and wife are told to start pulling pleasant surprises on each other at least once a week. “Once they start, a lot of times that old feeling comes back,” Jurgens says.

By the fifth week, it’s time for more treacherous explorations. Jurgens asks the couple to make up a list of gripes and positive things that their partner can do about them. (One woman complained that her husband shuffled over to the TV as soon as he got home from work, never pausing to speak to her. She asked that he spend five minutes with her before rekindling his afternoon affair with the television.) The lists of positive suggestions are exchanged, and the clients are told to fulfill one or more of the requests every week.

After three or four weeks of good deeds, Jurgens is ready to have the couple pull some emotional plugs. She uses a therapy devised by Dallas psychologist Harville Hendrix, called “the container exercise” (one spouse must receive the other’s pent-up bitterness, resentment, and emotion). “We have to teach them how to cope with their partner’s intense feelings, feelings that come from childhood and before the marriage,” Jurgens says. “You usually know that they’ve got it out of them when they start crying.”

Once that happens, the partners reverse roles. They begin trying to eliminate the behavior that triggers the unpleasant emotions. It can take months or it can take years; though her program officially is only 12 weeks long, Jurgens says most couples need six months of sessions or more.

Many couples who ask Jurgens for help are not willing to stick with a 12-week program. Many others break up without seeking counseling from anyone. But as far as Jurgens knows, no one who has undergone her whole therapy program has later gotten a divorce. “It hasn’t happened yet, but it probably will,” she says. “Even if they do get divorced later, the skills they learn will help them with their next relationship, or help them deal with each other as parents after the divorce.”

“Sometimes,” she adds, “a divorce is the best thing for them.”

It took her months to find a lawyer. “My husband is a son of a bitch, and I knew I needed to hire a son of a bitch, “she explained. She filed the divorce in February and left town.

“Being there in the courtroom was the most naked experience of my life,” she says. “Being there, just taking off your clothes for the world to see. And somebody who you don’t even know is making decisions that are going to affect your life and the life of your children. I felt like such a failure.”

IT IS NOT unusual, even among upperclass families, for divorce fights to get out of hand. Murders and suicides are frequently the products of “domestic disputes.” Louise Raggio, whose $150-per-hour fee discourages most folks of average income from hiring her, can name 12 domestic fights that put her client -or her client’s spouse or child -in the cemetery. About a decade ago she had a client, “a very fine person,” whose divorce drove her crazy. She didn’t want her three-year-old boy to suffer without her, so she decided to take his life as well as her own. “She smashed his head in, and then she didn’t have the energy to kill herself. She was sent to Terrell State Hospital, and then she did commit suicide. It was awful. It was the sort of thing you can never forget.”

Judge Linda Thomas has had one near-fatality in a divorce case since she took the bench in January 1979. A middle-aged husband from South Dallas asked the judge to order his wife not to harass or harm him – something the courts can do if there is evidence that bad things might happen without a temporary restraining order. The man’s wife was asked to testify on the matter. The first important question put to her was, “Have you ever threatened to kill your husband?” “No,” she replied. She was asked again, and again she denied it. “I’m going to ask you one more time,” her husband’s attorney said. “Have you ever threatened to kill your husband?” The wife, feeling badgered, looked at the lawyer and said, “I’ve told you, ’No.’ I have shot the SOB three times. I have missed all three times. But I have not threatened to kill him.” The man got his restraining order, but it didn’t do him much good. His wife took three more shots at him and finally aimed right. He was put in a hospital, and she was taken to jail.

MANY PEOPLE who avoid physical pain during and after their divorce proceedings are brutalized mentally.

One young couple in Judge Theo Be-dard’s court had been married for only two years -they had divorced previous mates to find happiness together -when their union cratered. They were middle-class, blue-collar folks, so dividing the property should have been simple. But when the wife went to their home to remove her belongings -it was his house from his previous marriage -she found that her husband had slashed all her clothes, cut her family pictures to ribbons, smashed her dishes, and destroyed every single item of her personal property.

Sometimes such nastiness is almost biblically just. Judge Pat Guillot recently heard a case in which the wife had been bragging to a friend that she’d slept with a man other than her husband. Unfortunately for the young woman, she was boasting over the telephone. Her husband, who wanted to make a call, picked up another extension in their home and overheard the conversation. He hacked up $4000 worth of her lingerie and filed for divorce.

Texas has updated its divorce laws several times in the past 15 years in hopes of “allowing people to put an unfortunate marriage to rest in a dignified matter,” family lawyer Tom Raggio notes. No longer must adultery or cruelty pleas be used to break the marital bonds. But the private eyes in their double-knit jump suits have been able to keep the 8 mm movies coming, every now and then, thanks to custody fights in which the character of mother and father can be key issues. Fathers, in fact, generally must prove that their wives are bad mothers or insane before the courts will take youngsters of “tender years” – say third grade and below – from their mothers. Once they turn 14, youngsters can tell the court which parent they want to live with. And yet during the past few years in Dallas County, most fathers who have fought before a jury to keep their children have won. “Of course, you don’t even go to the jury unless you are convinced that the father is the best horse in the race,” says lawyer Charles Robertson. Fifteen years ago, fathers got custody only if their wives were very bad or very crazy, says family court judge Dan Gibbs. Today, he adds, some mothers don’t even want custody, and some fathers are awarded custody simply because they are the better parents.

Several years ago, Judge Annette Stewart awarded custody of several children to their father because of their mother’s preoccuption with her bridge game. “She would go to lessons during the week, and on weekends she would go on trips to these tournaments, I think, because she had a friend who also went to them -a man,” the judge says. Nevertheless, the woman was awarded temporary custody of the children. Her husband got the kids back after the divorce trial, thanks to a private investigator who testified to the woman’s frequent flights from the family nest. “I wound up taking her out of the house and putting him in,” Judge Stewart says.

Couples with a keen appetite for battle, but no children to fight over, often resort to pets and occasionally to inanimate objects. Every judge or divorce lawyer in town knows of at least one couple who was willing to fight to the death over custody of their poodles. Judge Stewart handled what may be Dallas’ most celebrated animal custody case two years ago, when she presided over the divorce of two wild-beast trainers. Among the mutually desired possessions were several Shetland ponies, dogs, black jaguars, and elephants (among other creatures). Fortunately, they had two or four or six of most animals. “They had five elephants; that was the big problem. Evidently, you can’t have an elephant act without three elephants.”

“I’ve got this chain saw in my office, which two or three years ago was holding up a $6 million settlement,” says divorce lawyer Louise Raggio, perhaps the pioneer of Texas family law. “They both wanted that chain saw, which you could have bought at any store for $169. So I bought the man a chain saw with my own money. The woman didn’t want the chain saw; she just didn’t want her husband to have it. She gave it to me … She had complained that her husband kept coming into her house and taking things, so she’d vowed, ’He’s not going to get one more thing.’ “

Couples have some new incentives to go bare-knuckles over property matters, thanks to an April 29 ruling by the Supreme Court of Texas in a Dallas case involving Wanda Faye and John Samuel Murff. Mrs. Murff had sued on the basis of the state “no-fault” law and on the grounds of cruelty and adultery. She won $118,000 in family property plus $8500 in attorney’s fees, while her husband was awarded about $73,600. He appealed, saying that findings of fault had no place in division of family property. Fairness and the relative needs of both parties should determine who gets what, he argued. The Supreme Court disagreed with him, and local attorneys now wonder whether more and more spouses hungry for a little more property will accuse their husbands and wives of unsavory activities.

Judge Gibbs believes that people who mess up their marriages through adultery or cruelty should get less than half of the couple’s joint property. “If they dance, the piper must be paid,” he says. Perhaps his most unusual cruelty case involved a World War II veteran whose wounds forced him to wear a colostomy bag on his belt. “One time he got in a fight with his wife, and she pulled the bag off his belt and hit him in the face with it.” The husband thought his wife had been cruel enough to warrant a divorce, and the judge agreed.

In general, then, the divorce courts are not places where one puts one’s best foot forward. Even the happy divorcées walk from the bench wearing paroled-prisoner smiles. And yet every one of Dallas’ seven family court judges can tell a story with a happy ending.

JUST ABOUT EVERY lawyer in town can tell you that some clients walk right up to the courtroom door before deciding that they don’t really want a divorce. Judge Stewart has had one couple file for divorce, only to have a change of heart – five times. Judge John Whittington recently was taking routine uncontested divorces when a wife testified that the problem with her husband was that he worked too hard. Yes, the husband admitted under oath, he probably did work too hard. When his lawyer asked the routine question of whether he wanted to divorce his wife, the man surprised the entire courtroom by saying, “No, not if she’ll let me go home.” The judge turned to the wife, a lady of middling age and appearance, and said, “Can he come home?” “Sure,” the wife replied. Case dismissed.

When the divorce trial was over, she had been awarded $700 a month in child support, the house and furniture, and her car. He paid for about two months. She wanted to have him cited for contempt of court, but he pleaded poverty. Sure enough, his practice had gone to hell. His office had been padlocked, his phone disconnected. She thinks he was doing it on purpose, and it makes her mad. She’s working 50-hour weeks and can’t save 50¢. She got sick, and her sister offered to hire her a maid. “I don’t need a maid,” she told her sister. “Millions of American women get along without one.” To which her sister replied, “Have you looked at them?”

Sometimes her husband visits the kids and tells them he can’t see them more often because of their mommy. But she is surviving, and she is proud of that.

“I really feel like an adolescent. I’m finally beginning to taste all that freedom, and it’s fun. Unfortunately, I’m not 20 or 23; then I wouldn’t have all those responsibilities for the children. That is terrifying.

“Now I’m scared that somebody’s going to need braces. My house needs $4000 worth of repairs, and I don’t have $4000.”

IT IS SAFE to say that most men in Dallas and in the United States do not faithfully pay their child support. Dallas County’s child-support payment office supervises some 20,000 child-support accounts, which amounted to $36 million in 1980. In 1980, those 20,000 accounts produced about 14,000 complaints. John Turner, the county’s child-support enforcement officer for cases where children are on welfare, says that “probably 70 per cent delinquency is a fairly accurate estimate” of those fathers who pay late, or not enough, or not at all.

The U.S. Census Bureau conducted a survey of women who should have been receiving court-ordered child support in 1978, and found that only 39.8 per cent were getting everything they were entitled to, while 36.1 per cent received nothing. Even the husbands who made voluntary agreements with their ex-wives kept their promises less than 70 per cent of the time.

Some men seek to justify their failure to pay by failing to earn a living. Judge Stewart once tried a case in which the husband was a certified public accountant whose income inexplicably dropped 50 per cent between the time the divorce was filed and the time the case was tried.

It’s not uncommon for some husbands to lie or mislead the court about their incomes in hopes of getting off with small child-support payments.

Take, for example, the case of a top manager at one of Dallas’ most famous oil-related companies. He and his wife had a rather bitter divorce-there were allegations of cruelty and mental instability- and he offered her only $2500 in temporary support for herself and their two children. Heck, he said, he earned only $10,000 a month before taxes and $5000 a month after taxes. He couldn’t very well give them more than half his income while the divorce was pending, he argued. His wife’s lawyers were not convinced. The earnings figures did not include huge bonuses and benefits from stock options and other company fringes, they knew.

They also knew that the executive’s hefty expense account benefits -car, food, lodging, country club memberships – were not being counted by the husband. Since the wife’s team of lawyers and accountants could not get access to the company expense reports, they couldn’t count those benefits either. But by cross-checking family financial records, they could prove that the husband had spent only $100 a month on himself for the past several years for all his personal needs: clothes, food, travel, gasoline, entertainment, you name it. The husband, perhaps aware of potential problems with the IRS, paid his wife and children $4000 a month-$2000 for the kids and $2000 for the wife.

Even though Texas does not allow judges to impose alimony payments on ex-husbands (husbands who are not yet divorced often must support their wives until the break is final, and husband and wife can contract for alimony if they want), some men look on child support as gravy for their exes. “I’ve had men tell their wives, and admit to telling their wives, that they were not going to get any money because they are not going to work,” Judge Stewart says.

If a father seems to be shirking his duties to his children, he can be jailed and forced to stay in jail for contempt of court until the payments are made. If he has a job, he can be kept at a work-release center where he will be jailed at night, but set free on working days so he can pay his family. He also must pay the county $5 a day for boarding him.

Fathers who skip the state or drop from sight can be tracked through driver’s license numbers, Department of Labor files or even the Internal Revenue Service, enforcer John Turner said. The vanished daddies are caught about two-thirds of the time now by Dallas County’s child-support office. Like their impoverished ex-wives and their confused children, they found that divorce could not save them from the effects of a bad marriage.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte