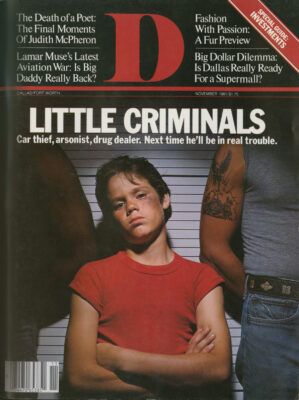

Let’s review your record, son,” says Judge Pat McClung as he sits before about 110 surly pounds of street punk, one kid out of the half dozen he sees during a normal court day. “In July 1980, you had something to do with the unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. Then in January 1981 you were involved with controlled substances.” He pauses. In a more obviously theatric setting it would be a Jack Benny pause, a “What-dodo-now?” pause. Judge McClung’s pause is clearly for effect.

“Now, no action was taken in these instances. We tried to shuffle them under the carpet, so to speak, and give you a break,” he says, glancing back at the papers and beginning again to read: “Then in February, we have another unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. A petition was filed and you didn’t appear.”

The judge’s eyes dart directly to the 14-year-old boy’s mother standing nervously before the bench. She is a few inches taller than the boy and twice as wide. Then the judge executes a partial pirouette on the wheels of his ball-bearing chair and addresses the court-appointed attorney, a helpful-looking man in a poorly cut suit.

“In March, a charge of burglary for which we put him out on probation. When he broke that, we placed him in the Dallas County Youth Village. And then he ran away. Twice.”

The boy redistributes his weight by et’s review your record, son,” says Judge Pat McClung as he sits before about 110 surly pounds of street punk, one kid out of the half dozen he sees during a normal court day. “In July 1980, you had something to do with the unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. Then in January 1981 you were involved with controlled substances.” He pauses. In a more obviously theatric setting it would be a Jack Benny pause, a “What-dodo-now?” pause. Judge McClung’s pause is clearly for effect.

“Now, no action was taken in these instances. We tried to shuffle them under the carpet, so to speak, and give you a break,” he says, glancing back at the papers and beginning again to read: “Then in February, we have another unauthorized use of a motor vehicle. A petition was filed and you didn’t appear.”

The judge’s eyes dart directly to the 14-year-old boy’s mother standing nervously before the bench. She is a few inches taller than the boy and twice as wide. Then the judge executes a partial pirouette on the wheels of his ball-bearing chair and addresses the court-appointed attorney, a helpful-looking man in a poorly cut suit.

“In March, a charge of burglary for which we put him out on probation. When he broke that, we placed him in the Dallas County Youth Village. And then he ran away. Twice.”

The boy redistributes his weight by rocking onto the balls of his feet, then resting back on his heels.

“That was five months ago,” the judge says. His voice is strained but still steady. “Where have you been living since that time?”

“On the streets,” the boy murmurs without looking up.

“On the streets.” The judge repeats the boy’s words.

“I know how to take care of myself.”

“You do. Well, what do you think I should do now that we have another burglary on file here?”

“I want to go back to the Youth Village.”

Judge McClung leans back, casts his eyes up to the fluorescent lights and begins to rhapsodize. It’s a familiar refrain, one that is almost like a sermonette, a daily word that he can recite off the top of his head and from the bottom of his heart.

“The problem I have with him is that he’s burned his bridges, and I can’t overlook the fact that this young man has been involved in five felonies. I can’t reform the world. I can’t get inside his head and make him change. All I can do is give him a chance.”

That chance, that right to change, is what crime-committing children under the age of 18 have been offered since a separate juvenile justice system was established in 1899. This time, the chance will take the form of a commitment to a facility run by the Texas Youth Council (TYC). The Dallas County Youth Village -where the boy had wished to return – has a softer reputation; it is a place for “better” boys.

This kid has just crossed a fine line. Judge McClung tells the boy that there will be no bars or fences at the TYC home. He will have to go to classes, the judge says, and it may be his last opportunity to learn a trade. The case is then dismissed, but it won’t be closed until TYC has paroled the youth for what it feels is an appropriate period of time, or until he turns 18. Parole will inevitably come first, and statistics show that this child is probably going to break the law again. And fairly soon.

One of Judge McClung’s favorite anecdotes-one that he repeats -is about an encounter he had with a newspaper reporter three weeks after he took the 305th Family Court bench in 1975. “He asked me what was wrong with the juvenile justice system and I said, ’I don’t know. But what we’re doing isn’t working’, ” he says. “I didn’t know how wise a judge I was. That was over six years ago, and I’m still saying the same thing.”

Things have changed a great deal in six years, and yet the changes have only created new problems that prevent the system from working. In his address of Oct. 12, 1979, before the New Jersey Reform Conference, U.S. Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti said that “in the last few years, several states have ’recriminalized’ juvenile delinquency, redefining it as a crime rather than a social disorder. Prosecutors have been given more authority to deal with juvenile cases, and the adult courts are playing a larger role as well. The problem is that the system still lacks uniformity of purpose and outlook and is therefore as unpredictable, if not more so, than it was several years ago. . . the present lack of predictability and uniformity undermines our ability to inculcate in our youth a respect for justice and the legal system.”

Texas has come great distances in the standardization and unification of its juvenile courts; most observers believe Dallas County’s juvenile department is the second strongest, if not the strongest, in the state. Most of the people involved with the juvenile system are working frantically to abate delinquency and the numbers of juveniles enmeshed in it. The problem then is not so much with the individual administrators, but with the gaps between departments that could be better bridged with better communication than with new mandates and laws.

Statistics still show that at least 28 percent of all felonies recorded in the U.S. are committed by 2 percent of a diminishing juvenile population at a cost of an estimated $10 billion in direct damages annually. Of the arrests for the eight most serious FBI “index” crimes – murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft and arson-juveniles accounted for more than 41 percent.

In Dallas, about 42 percent of the people arrested for burglarizing buildings last year were under 18. Of the 2,375 kids referred to the juvenile department on felony charges, 1,012 were white, 1,005 were black and 330 were of Mexican descent. Even more interestingly, of the children awaiting a disposition from the court, 553 were re-arrested for jailable misdemeanors and felony offenses before their first petition had been fully processed. Authorities say the numbers are less impressive than the gruesome nature of some of the crimes.

“The laws that describe the kind of child eligible to stand trial as an adult haven’t changed,” says Hal Gaither, head of the district attorney’s juvenile division. “But more and more of them can qualify.”

Fear and frustration are causing many people to forsake the old “boys-will-be-boys” soft line. “A 9-year-old could walk in here and blow you away with a shotgun, and technically, it would be illegal to make him stay in jail overnight,” says Frank Dennison, the former superintendent of the Rotary Townhouse. “Is that justice? Is that serving in anyone’s best interest?”

At a conference sponsored last month by the Dallas County Juvenile Probation Officers Association, a policeman shocked many members of the social service-oriented audience when he said, “From my observations, there are sick kids and there are mean kids. Why can’t we get those mean kids on death row?” Cries like this for harsher sentences, and requests to certify more teen-agers to stand trial as adults run counter to the Family Code revered in juvenile courtrooms. Law enforcement officers are becoming vocal in their support of a crusade against liberalized “bubble gum” laws that are supposed to aid the rehabilitation of a child by giving him a break. The legislative emphasis has shifted to focus unwaveringly on getting bad kids off the streets. Already, the states of New York, Connecticut, North Carolina and Vermont have legislated a lower age requisite to stand trial in “kiddie” court- from 18 to 16. Similar legislation is brought up in Austin every year, and the state legislature’s criminal jurisprudence committee is questioning the necessity of having a separate justice system for juveniles.

During the past six years, the public’s attitude on juvenile delinquency has shifted a full 180 degrees in reaction to a runaway crime rate that seems to jeopardize our safety at every turn. It’s hard to believe that in 1974 -only seven years ago – we were at the peak of our benevolence after reading that the state of Texas was reported as having some of the worst managed, most brutal juvenile institutions in the country. The pendulum has swung from one side to the other, and still the juvenile justice system doesn’t work. With all the talk of toughening up, we’re continuing to let a large number of little criminals slip through our checking processes.

While there are intricate differences from case file to case file, a clearly characteristic pattern begins to emerge from the probation officer’s own hand. It goes something like this:

Jan. ’81: Child commits a crime, is arrested, detained, and placed on six to 12 months probation depending upon the severity of the offense. Child released from detention center to parent.

Feb. ’81: Child remains with parent on probation and is said to be making a “good adjustment.”

May’81: Child still with parent, adjustment deteriorating.

June ’81: Child in detention center. Case pending in court on new referrals from Dallas Police Department.

And over, and over and over again: “The parent is the ticket.” You’ll hear that remark from every caseworker. “You can’t rehabilitate a kid if you have to return him to the same bad home, time after time. You’ve got to resolve the problems at home because that’s where the child’s going to have to live unless he’s bad enough to become a ward of the state.”

“The basic right of a juvenile,” says Ohio Judge Walter Whitlatch, “is not to liberty but to custody.” Just so, the juvenile justice system is set up to protect society from a potentially dangerous youth while preserving the best interests of that child. Both child and family are supposed to be ameliorated by the arrest-detention-release transaction between their household and the state, but it rarely seems to work that way. The child is too frequently returned to society a little bewildered or just plain angry about the whole thing.

When a child is arrested, he is referred to the juvenile department’s intake division where the district attorney’s liaison can research the case, draw up a hasty remedy to the immediate problem and determine whether a petition to the court should be filed. Frequently, at this stage a child will be warned that the court “means business,” and if he ever gets in trouble again, he’ll find himself in front of an uncompromisingly stern judge. This scare tactic can work successfully, particularly if part of the child’s arrest experience has included time in the detention center on Harry Hines Boulevard. The institution is no longer the scandalous den of disease and disorder it was 10 years ago when kids were sleeping on its dirty floors, and others were hanging themselves to death from ventilation ducts. The detention center’s purpose has never been punitive in nature, but it is a tough place, uncomfortable enough to give some children pause.

An estimated 47 percent of all cases are dismissed at the prepetitioning stage, but if the offense is fairly serious, the intake officer may press for the filing of a petition in juvenile court. The judge can process such a petition in three ways: (1) it can be dismissed or nonsuited if the subject skips town or if witnesses or plaintiffs don’t appear to testify or press charges, (2) it can be transferred to adult criminal court in Texas if the child is over 15 and has committed either a series of serious offenses or one major, violent offense; or it can (3) lead to an adjudication hearing in which the juvenile’s conduct may be deemed delinquent by the court. A disposition hearing is men held and the presiding judge administers justice by considering the probation officer’s placement recommendation, which is determined according to the officer’s research. Often another factor is considered: the county’s placement budget. Probation officers claim that frequently youngsters who should be placed in juvenile home simply go back to their own homes because the county can’t afford to institutionalize them.

The child placed on probation is either sent home with a series of conduct rules to follow, or placed in the custody of a relative, guardian, foster parent, private placement facility or an institution run by the county or the state. In short, a juvenile case is considered a civil suit, but its procedures are far more criminal in nature.

Plug in a few case histories and you’ll get a good idea of how the system works and how easily it can falter -or fail.

In October 1977 (when juvenile justice in Dallas was a little more liberal and loose) Bobby was chastised and given six months informal probation, or “adjustment,” for his involvement in the burglary of a building in North Dallas. He was 12 years old. His home situation was described as “real bad”; his father had a long, involved arrest record, and his mother was incapable of supervising Bobby properly. During the next month, another burglary was recorded in his file, but the complainant dropped charges. By December, Bobby had been caught burglariz-ing yet another building and was placed on formal court probation for a year. His probation officer thought he had responded well to the weekly reporting sessions, and when Bobby’s probation was up, there seemed to be no reason not to close his file. It was reopened, however, in 1979 when Bobby was charged with burglary and truancy. In the third month of his renewed court probation, he was caught sniffing paint. Probation was extended. Three months into the renewed probation term, a charge of criminal trespass was noted in Bobby’s file, but the court did nothing about it. In December 1979, Bobby was arrested for carrying a firearm from the trunk of a car to an apartment building. Moments later the gun was used by someone else to shoot a man in the groin. The adult who fired the weapon was sent to jail; Bobby was sent to the Dallas County Youth Village. Eleven months later, he was released with a note of “satisfactory adjustment” in his file. Then last April, a charge of theft was noted, but again the court took no action, and in August Bobby was returned to the Youth Village for a violation of the Controlled Substances Act and for the unlawful carrying of a weapon. Quite a record for a 16-year-old boy.

Or take Leroy. He was born illegitimately and raised by an elderly aunt until he was 5 years old when he was moved back in with his mother. He ran away from home for the first time when he was 12. Leroy’s case was turned over to the Child Welfare Department because he was walking with a pronounced limp and was complaining that his mother had been tying him to his bed with scarves and beating him with an extension cord. After authorities consulted with his family, Leroy was sent to live with his aunt. Between January and August 1978, Leroy ran away from her home six times. The aunt had a difficult time controlling him, so Leroy began to spend more time with his mother. She wasn’t beating him anymore, Leroy explained, but he was having considerable difficulty getting along with his brothers and sisters. During that period Leroy was detained, released on probation, and tried for stealing sausage sticks and candy from a five-and-dime store. In September, Le-roy’s aunt was taking care of him again when he pulled a knife on one of his cousins. Leroy was sent back to live with his mother.

When his formal court probation for the stealing incident had expired, his probation officer (who probably suspected he’d be hearing from Leroy again) was obligated to write “Case Closed” in Leroy’s juvenile file. Sure enough, Leroy was back in detention this February on an aggravated assault cnarge. He had attacked a female co-worker at his new place of employment, forced her to unbutton her blouse and then threatened to kill her. He was ordered by the court to enroll himself in a mental health program in Dallas and is now living at the Dallas County Youth Village, where he’ll be eligible for release next spring if he behaves himself.

Why weren’t these children stopped before they had the opportunity to do additional damage to themselves and their surroundings? Cases like those of Bobby and Leroy illustrate how ineffectively the weekly probation reports and psychological tests were put to use. The people responsible for repeatedly placing these kids in their homes were obviously without the time, money or inclination to see that the children were monitored as closely as they needed to be and for respectable periods of time.

The most obvious -but in many ways precise-solution to the system’s shortcomings is money. Juvenile Judge Craig Penfold of the 304th Family District Court recently compared the monies appropriated to the two justice systems (adult and juvenile) and found a poorly proportioned till. In 1978, Dallas County budgeted $22,290,924.76 to the adult system and only $6,202,477.76 to the juvenile: 79 percent of the funding for criminals over 21. In 1980, juvenile justice got even less: $5,467,665.99 as opposed to the adult system’s $22,425,273.92; that’s 19.6 percent compared to 80.4. Yet it’s estimated that at least one-third of all felonies are committed by juveniles under the age of 18.

“I showed’those numbers to the county commissioners this year,” says Penfold, “and they gave us every penny we’d asked for. But just think of what we could do if our funding equaled the percentage of crimes that are attributed to juveniles – say, 30 or 40 percent.”

A probation officer says, “In my mind, you can take all the people in the adult correctional system and bury them in a big hole. There’s no use in trying to rehabilitate them. Every possible dollar should go toward the juvenile system.” Assistant Director Rick Hartley at the Texas Department of Corrections says the percentage of adult inmates who started their criminal careers as children is “large”; they’ve just never had the time to make an accurate count.

A second thorn in the juvenile department’s side is its unpredictable and sometimes uncooperative relationship with law enforcement. Juvenile arrests for violent offenses increased in the United States from the early Sixties to 1975, then began a period of decline. Last year’s referrals for personal violations and burglaries in Dallas County were actually down to the same number of referrals per 10,000 juveniles as in 1959. Sounds great, huh? Forget it. Police are reluctant to arrest kids these days unless the offense is extremely serious.

One policeman expresses himself quite | effectively: “Why should I take the time to arrest one of those little shits, when within a few days I’ll find him back in the neighborhood doing the same old thing? The kids think it’s all a joke. Our nickname for the detention center is the ’Dallas County Revolving Door’.” Says another officer, “I’m not going to turn my back, but then I’m not going to go out of my way to arrest a kid either.”

The bridging of gaps between the juvenile department and the city and suburban police was also a topic discussed at a Juvenile Executive Board meeting on September 14. Al Richard, Dallas County’s chief probation officer since last February and a former police officer, had just completed his justification for a police department liaison when Judge Snowden Left-wich Jr. of the 192nd Civil District Court intervened. Apparently, this was the first he’d heard about the tensions between probations officers and police. An exchange between Richard and Leftwich shows just how out of touch some members of the executive committee board really are:

Leftwich: I mean, was this idea about the police not arresting juveniles something from a specific remark or is it a rumor?

Richard: Well, it was a specific remark made when I was talking to police officers.

LEFTWICH: I would be shocked if someone told me that, quite frankly.

RICHARD: Well, see … statistically, juvenile crime is not on the rise, but in talking to police officers, they’ve said that they’re not arresting juveniles because the courts don’t do anything about it. It was an expression of frustration on their part, I think.

LEFTWICH: I’m sure they’re frustrated, but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t do their job. At least they’ve got to keep records and keep them straight. I find their attitude frustrating.

JUDGE McCLUNG (chuckling): Well, I found it frustrating when I first heard about it six years ago, but I’ve sort of gotten used to it.

RICHARD: The police were saying something about how the same juvenile is arrested two or three times, and then he’s still found loose on the street.

LEFTWICH: Well, two or three chances is okay with me as long as they keep the record straight. I don’t care what their age is, the kids should be met with what they’ve done. My point is that it ought to be called in their hand, irrespective if someone is going to release them tomorrow.

Richard: Well, we’ve got to close those gaps and work with police to close those gaps.

Richard’s goal as probation chief is to prove that more juvenile supervision from his department will result in lower recidivism rates (the percentage of offenders arrested again). He is placing key people and department liaisons on the streets to break up young gangs and cliques, and he’s expressing an interest in progressive programs being used in other states.

The Dallas Police Department is still conducting a first offender program that began in 1973 (at the peak of widespread disillusionment with the detention center and the juvenile department) with a $2.5 million grant and is now subsidized by the city. The plan was to cut juvenile delinquency back by 30 percent. A psychologist (the position is no longer a part of the program) and more police investigators were hired to work in the youth division. Superintendent Levi Williams claims the long-term program served about 600 to 700 youths last year and that their recidivism hovers between 21 to 27 percent. Of course, serious offenders whose parents fail to participate in the counseling sessions are not served at all. Their recidivism rate, Williams admits, is 100 percent. These are the kids whose files at the juvenile department eventually grow to about an inch and a half thick. These are the kids who -like the street punk in Judge McClung’s courtroom -keep coming back.

But even if the juvenile department and police got along, and even if juvenile justice administrators were allotted their proportionate share of county funds, a third major inadequacy of the system would still exist in Dallas. It is a national problem as well. There aren’t enough placement options available once it has been decided that a child should be taken from the home, and the available facilities, by and large, aren’t very good.

“Frequently a juvenile judge only has the possibility of returning a juvenile to his home or putting the child on probation or in an institution,” said U.S. Senator Birch Bayh after serving on a Senate subcommittee that analyzed the problem. “What is needed are programs in communities aimed at preventing children with a high probability of delinquent involvement from behavior leading into the juvenile justice process. At each step along the way that children seem headed for trouble, the community should be able to choose the least amount of intervention necessary to change the undesirable behavior.”

Of the 97,115 juveniles placed in a state or local correctional facility nationally in a year, one survey indicates at least 28 percent might be considered a rehabilitation failure, with 9.2 percent being referred back to court for revocation of their parole status after discharge and 18.8 percent escaping from the institution. Since the type of community-based programs Bayh mentioned have never been supported on a large scale by Dallas citizens, many juvenile authorities believe that the emphasis should be placed upon improving the placement facilities we already have and working to get the community more involved with them. Places like Vernon Drug Center, the Juliette Fowler Home and the Terrell State Hospital’s Adolescent Unit work with the psychological and physiological ills of delinquent children. They deal with kids whose illegal actions were the symptoms of a definable problem, and they thereby meet with a certain degree of success. For delinquent kids the court considers more misguided than sick, there are a number of survival camping programs and almost a dozen youth homes and special schools on each judge’s list of facilities. Among the strongest of these is the Dallas County Youth Village, formerly known as the Boys Home, and it is not an ideal placement for the violent offender. But if a child breaks the law repeatedly -after formal court probation and one or two attempts to successfully keep him away from a negative environment at home -there is only one option, one last order short of transferring him to an adult court that could put him in a penitentiary: The Texas Youth Council.

It would be tough to think of any state-run agency as maligned and unprized as the TYC. Only 3 percent of all juvenile offenders are committed there annually. However, that percentage contains the hardest, meanest core of kids. “I sometimes wish we could just scrap the whole thing and start all over,” says Judge Pen-fold’s referee-master, Dan Street. “TYC is a joke and a disgrace,” says a juvenile department employee. TYC was targeted and used as a public scapegoat by county juvenile workers at the probation officers’ conference. They were particularly disenchanted with TYC’s parole procedures, procedures they labeled as unvigilant.

First, some TYC history. In 1974, U.S. District Court Judge William Wayne Justice ruled after hearing uncontested testimony in the case Morales v. Turman that the disciplinary procedures at all six juvenile institutions run by TYC were cruel and unusual, and that two of those schools, Gatesville School for Boys and Mountain View, should be closed.

“One of the punishments they used at Mountain View,” says Al Richard, “was to get someone to jog in place on either side of a kid’s head near his ears and the sound or something burst some eardrums.” Sadly, “fewer than 10 percent of the TYC wards had committed a violent crime,” says author Charles Silberman in Criminal Violence, Criminal Justice, “more than 25 percent had been committed for ’disobedience,’ a catchall category for such offenses as running away from home, truancy and being an ’ungovernable child’.” It took the council some time to recover from that kind of publicity.

Thus began a new period for TYC, a remorseful easy-on-the-kid era in which youthful offenders committed to TYC homes for violent crimes were sometimes deemed ready for parole after a few weeks. Even today, the average stay at a training school is only about eight months. From there the child is sent to a halfway house or is simply released on parole. The length of time a child stays at TYC is not a decision of the court, and he is technically beholden to the council on a suspended sort of commitment until he reaches age 18. Often, the home situation a child returns to upon parole has not improved; sometimes the child’s return even creates new tensions.

The Dallas TYC office employs seven parole officers, each with an average daily caseload of 62 youngsters. “What they do to keep that number down, you see,” says Street, “is discharge a case when he’s 17 years old instead of 18 if he hasn’t had any violations. They keep getting new parole cases, and they can’t keep all the old ones. I had one kid in here recently who’d been on TYC parole for eight months, and he said he’d never met his officer.”

A Family Code amendment said to be forthcoming from Judge Penfold’s office proposes mandatory counseling for the families of kids under TYC’s authority.

“It may be that TYC will never handle parole effectively. If that’s so, then county parole officers here should do it in exchange for supplemental county funding,” Penfold says. “If TYC had enough good parole officers, they could find good relative placements.” A new governor-appointed Juvenile Probation Commission was set up this year to, among other things, re-evaluate TYC and, according to Penfold, “genuinely support it.”

As it now stands, TYC revokes the parole it has granted to about 7.7 percent of its wards annually. “It should have been three times that many,” says Dan Street. About 78 percent of the revocations occurred when the child got out of TYC and committed a property offense; about 13 percent of TYC’s parole revocations occurred after the child had committed a violent crime. For this, the state is spending $31,981,204 on TYC this year.

Judge Penfold also wants to see a lengthening of TYC’s jurisdiction so that hard-core 15- to 17-year-old delinquents can’t squeeze between cracks separating the juvenile and adult systems. If a 17-year-old was adjudicated on an aggravated assault charge this year, he could be sent to a TYC home until his next birthday and then would be released automatically. “We should be able to make a determinative sentence,” Penfold says, “so that TYC could hand him over to the Texas Department of Corrections, and then they’d keep him until he was 25. That would serve as a really good deterrent.”

If some of the flaws are legislated out of the system and if the state and county facilities improve, then judges could commit juvenile offenders into their jurisdiction with a feeling of good faith. If repeat offenders and violent delinquents were comfortably situated at TYC, the county system might be able to rehabilitate younger, more malleable kids. “Initially, at least, juveniles expect some kind of punishment when they are found guilty of behavior that threatens the safety and security of others,” Charles Silberman says. “If nothing happens until the fourth or fifth offense (or in some instances, the ninth or tenth), young offenders are persuaded that they have an implicit contract with the juvenile court permitting them to break the law.”

Breaking the cycle of events that creates the vindictive adult criminals now overcrowding our jails will take money and coordination. The money may be hard to come by now that taxes are getting cut, not paid. The coordination? The juvenile justice system in Dallas is so fraught with power-playing, personal jealousies and dashed dreams that the juvenile department hallways seem like corridors of war.

This war against juvenile crime is conducted in secret on two levels. First, the children’s records are not computerized in central depositories; the system even allows for the destruction of files if a subject is at least 23 years old and has been out of trouble for two full years. But the real secrets go beyond the files, and the closed-door activities of the various administrators are like tempestuous domestic scenes played out in public housing projects.

Some of the probation officers say they don’t like working with Judge McClung because he “makes us look bad” in the courtroom. If Judge Penfold says he needs a court administrator, Judge McClung is quick to say that he needs one, too. There’s no love lost there. Dallas County has been through five chief probation officers in as many years. “The best chief,” says one source, “would stand about three feet high and have big lips on either side of his head so he could kiss both judges’ behinds.”

Police think detention center administrators are derelict in their duty. District Attorney Henry Wade is said to be placing “less than his best people” in juvenile court. McClung is said to give the district attorney a hard time because as judges go he is a stickler for probable cause. And everyone resents TYC. Not a meeting goes by without someone standing up and humiliating another. In the meantime, probation officers are reduced to behaving like prisoners of war; they pass secret notes to visiting reporters and do a lot of worrying about the coming judicial elections. “Sometimes we wonder who’s on probation around here,” one officer says.

“If you stick around long enough,” says an experienced juvenile department employee, “you’ll begin to see juvenile justiceas a metaphor for life. It’s screwed up.Crime will always be with us. Poverty willalways be with us. Juvenile crime is like acontinuous stream of water coming out ofa faucet. Your mind tells you it has all theproperties of a substance: It exerts force; ithas shape; it seems solid. But the minuteyou try to grab it, it fragments. Your handgoes right through. You’ll never find theanswers. You’ll never get it right. Andwhat all this time we’re failing to realize isthis: We need to turn off the faucets andstop it at the source. But it’ll never happen. That’s the single most grievous prob-lem. It can’t happen.”

Related Articles

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert

Things to Do in Dallas

Things To Do in Dallas This Weekend

How to enjoy local arts, music, culture, food, fitness, and more all week long in Dallas.

By Bethany Erickson and Zoe Roberts