THE BEST VIEW OF THE DALLAS SKYLINE CAN BE SEEN BY standing at the corner of Kiest Boulevard and Magna Vista Drive and looking north from the bluff that rises sharply out of the Trinity River bottoms. The spot provides a panoramic perspective over the outstretched prairie that civilization and time have covered with office towers and freeways. At night it is almost breathtaking. But most Dallasites will never see that view because, quite simply, the corner of Kiest and Magna Vista might as well be in another country. That particular street corner is located near the apex of a 10-mile deep triangle that most whites euphemistically call “South Dallas.” It is, more correctly, black Dallas. And the only distinct feelings most whites have about that part of the city is that they wouldn’t want to be there at night.

Dallas, geographically at least, is one of the most segregated cities in the nation. Seventy-two per cent of Dallas’ 265,594 blacks live in a triangle that runs from Fair Park in the north to Pleasant Grove in the east to the vicinity of Red Bird Airport in the west. (The black Chamber of Commerce estimates there are more than 310,000 blacks in Dallas County.) Inside that triangle, you can drive for miles without seeing a white person except for the ubiquitous police patrolmen or an occasional deliveryman unloading his goods at a cafe or a food store. North Dallas is the reverse: virtually all white. The 1980 Census data for the census tract around NorthPark Shopping Center shows the neighborhood to be 99.795 per cent white, .0012 per cent Asian, and .0012 per cent “other.” No blacks. The only blacks to be seen are the maids, the yardmen, and an occasional cop passing by in his patrol car.

Dallas’ segregated living patterns draw their origin from the days when the city’s only black residents were slaves. When the Civil War ended, the city fathers ordained that all blacks must live outside the city limits. Twenty-five years ago, Dallas blacks were still sitting on the backs of buses and drinking only from water fountains marked “colored.” Time has done a lot to change that. Integration in Dallas has both the law and the public will behind it. But there still remains a wide abyss between white and black Dallas. As one typical white respondent to a D Magazine opinion survey put it: “I’m not a racist. I don’t have anything against blacks, and I don’t think I am better than they are. It’s just that I don’t have that many thoughts about blacks, period. They aren’t that much of an issue in my life.”

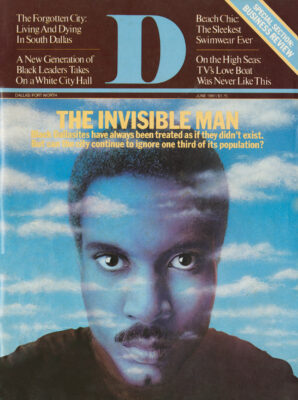

Yet that same opinion survey (see page 97) showed that today, two decades since integration became the law of the land, the majority of both the white and black communities think Dallas is a racially segregated city. And a majority of both races think Dallas is a city with racial problems. At the center of those racial problems is doubtless a lack of communication, a lack of understanding, a basic lack of knowledge by the majority of a race of people who make up one third of the population of the city. The black Dallasite is still, for most of us, the mystery man, the invisible man. It is in an attempt to bridge that abyss of misunderstanding that we sent a team of reporters into the ghetto. The series of articles that follows is a compendium of experiences of South Dallas, frustrations and hopes, the aspirations and the dreams of the invisible man: the black Dallasite.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman