THE LAST TIME LOU ANN LEE saw her mother, the woman was kneeling by the bedside in their tiny frame farmhouse, praying aloud. “Please, God,” she was begging, “please don’t let me die with this baby.” The prayer went unanswered. A few minutes later, Lou Ann’s mother died in childbirth. Lou Ann was 11 at the time, too young to be of much help. And Lou Ann’s father, who had abandonedhis family long before, was nowhere around whenLou Ann’s mother needed him. Lou Ann Lee spent that night staring at the ceiling, wondering why her mother had to die and leave her alone. At daybreak, the young girl walked to her grandmother’s house. Soon after, they came and took Lou Ann’s mother away.

Now, 20 years later, Lou Ann Lee is living out her mother’s legacy: fatherless children, poverty, and pain. It is a legacy thousands of black women, maybe millions, have lived out for generations. Lou Ann has had trouble with all four of her babies: All of them have been born by cesarian section. The four children – Kimberly Rochelle, 6; Marcus Dewayne, 4; Jasmine Nicole, 2; and Cora Roishun, 18 months – share a 450-square-foot apartment and $271 in food stamps a month with their mother. To the older children, a father is just a memory of an angry man who used to beat their mother up. The two older children and the two younger ones have different fathers, but they all have one thing in common: Their father has deserted them. Now the most important man in Lou Ann’s life isthe postman, the man who delivers her monthly allocation of food stamps and the $165 monthly welfare check. The postman is quite popular in South Dallas, for it is there that the vast majority of the 10,086 black women who are the wards of welfare-the infamous Aid to Dependent Children or ADC-spend their lives. (Black women make up the overwhelming majority of welfare recipients in Dallas. Even though blacks represent only about one third of the city’s population, they represent 73.3 per cent of the ADC recipients.)

Lou Ann is the stereotypical welfare mother in a lot of ways. She is young; she is devastatingly poor; she has all but lost her faith in human nature. She devotes most of her time and all of her thought to survival.

“Love is a four-letter word,” she said one Saturday afternoon as she sat in her cramped kitchen, holding her youngest child. “Love doesn’t pay any bills. Love doesn’t put shoes on your children’s feet. Think only of yourself and of self-preservation. Don’t get into somebody else’s trip, because if you do, you’ll eventually fall victim to the system, and if you do, the system will defeat you. It happens every time.”

Lou Ann’s house is typical of the kind of hard-core poverty shack found in South Dallas. It has no air conditioner or heater. No refrigerator. Just a stove she is buying on the installment plan from her landlord.

The little green shotgun duplex in which Lou Ann and her family spend their lives measures roughly 10’ by 45’, and is divided into three rooms: a living room, a bedroom, and a kitchen. It will never be in the Parade of Homes. The front yard, if you could call it that, is smaller than most Dallasites’ living rooms. The house, which sits on a cross street just off Martin Luther King Boulevard (formerly Forest Avenue), is just a stone’s throw from Fair Park, as the broken window in the back of the residence attests.

Minding the family budget is a little more difficult for Lou Ann than for the housewives across town. The $271 in food stamps doesn’t go far enough to feed a family of five for amonth. And the $165 ADC check she gets every month is divided accordingly: $65 for rent, $30 for gas, $30 or more for electricity, and $15 or so for water. A telephone is about as accessible to Lou Ann as a Lear jet. What’s left of the cash goes for an occasional box of laundry detergent (you can’t buy soap, toilet paper, or other such products with food stamps). But she usually opts to spend the extra cash on food. Right now her closet is filled with clothes that she can’t afford to wash because she spent what was left of her ADC check on food for the children.

“Lots of times I get some potatoes and cook them for the kids because you can get a lot of food in your stomach for your money,” she says. “Sometimes after all the kids eat, though,there isn’t anything left for me. I never thought I would have to go to bed hungry – it never happened to me when I was working-but sometimes I do go to bed without eating. I think about Reagan in the White House eating steak for dinner, or Bob Folsom out in North Dallas eating lobster or something. I’m sorry, but I can’t help but get mad when I think about that.”

In many ways, Lou Ann Lee is not your average welfare mother. She is articulate and relatively well educated. She was the salutatorian of her high school class in Jefferson, the small East Texas town where her grandmother raised her. At 19, Lou Ann came to Dallas seeking opportunity. She came filled with hope. And for the first few years in the city, her hope proved to be justified.

At age 20, she married a man with a good job. During their eight years of marriage, the couple had two children (Kim-berly Rochelle and Marcus. De-wayne) and bought a house on Tyler Street in Oak Cliff. Lou Ann spent nine years working as an operator for Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., earning $300 a week by the end of her tenure. With the money the two of them were making, Lou Ann and her husband could afford to live the good life; with amortgage and a couple of cars, they were middle-class Americans in every sense of the term. But about four years ago, Lou Ann’s middle-class Camelot began to fall apart. She made some mistakes that would change her life.

“I met this other man, and I got pregnant by him,” she says. “The day my husband found out about it, he kicked the kids and me out on the street.”

Lou Ann found a room with a woman who lived in the Fair Park area. The woman agreed to take in the two children and the expectant mother after Lou Ann put up some dishes and other household items for collateral.

Shortly after Lou Ann settled into her new living arrangement, Kimberly, her daughter, became ill. The doctors at Parkland Hospital diagnosed her illness as pneumonia, and put her on a lung machine. For a few weeks after that, Lou Ann spent herdays riding the bus between South Dallas and Parkland Hospital and her nights working the graveyard shift at the phone company. She had volunteered for the night shift so she could take care of her children during the daytime. Just when Lou Ann thought things couldn’t get any worse, they did. When Lou Ann returned to work after Nicole, her third child, was born, Southwestern Bell fired her for allegedly failing to fill out the proper maternity leave request form.

Lou Ann’s decision to seek shelter with Nicole’s father turned out to be a bad one. The man was a hopeless alcoholic who took out his frustrations by beating up Lou Ann and the children. “I don’t know why he did it,” she says. “But I stayed with him andput up with it for three years. He had me walking around like a zombie. I guess I stayed with him out of guilt. I figured I must be reaping what I had sowed.” After Nicole’s father left Lou Ann, she moved into a rent subsidy house in Oak Cliff. By then she had four children to feed, and the federal subsidy on her rental payments helped.

It was in Oak Cliff that Lou Ann met Greg, a young man who wanted to move into the rent subsidy house with Lou Ann and her children. “When I said no,” she recalls, “he came after me with a gun. He broke out all the windows in the house and held a gun on me and the kids all night. The only thing that got him to leave was when I told him that my welfare caseworker would be coming soon, so he’d better go.” As soon as Greg left, so did Lou Ann and the children. She packed the kids and all her belongings into a taxicab and went to a shelter for battered wives.

After spending some time in the shelter, she was offered a couple of jobs, but her welfare caseworker advised her to turn them down. With four children, she’d have considerable day-care expenses in order to work. She’d have to clear $700 a month to be in the same economic shape she is in withher $165 ADC check and her $271 a month in food stamps. She is in an economic trap.

And there’s another problem. Lou Ann is stressed out. She is an emotional wasteland. Because her nerves are shot, she now has one thing in common with some of the more affluent housewives across town: A doctor has put her on Valium.

Now Lou Ann spends her days watching a small black and white television that was a gift of charity, watching her kids run back and forth through the three-room house, watching her life slip away.

Lou Ann fully realizes that most working people would consider her a welfare chiseler. “That’s kind of strange,” she says, “because when I was working, I resented all the money the government was taking out of my check, and I can remember going around and saying, ’Why should I have to support somebodywho won’t get off his ass and get a job?’

“Now I have to look at it from the other side of the fence. I’m not making any excuses, but I was thrown into this situation. People with jobs and families don’t realize how lucky they are… Now Reagan wants to cut back on welfare. I’d like to show Reagan the dirty clothes I have stacked up in the closet and can’t afford to wash right now. I figured there are 22 loads worth. I’ll wash them in the bathtub. I see to it that me and the kids stay clean. But I don’t have the money to use a washing machine. I would consider that a privilege.

“When Reagan says he wants to cut out welfare, he’s talking about taking a dagger to five people. Me and my four kids. Does cutting out welfare create any jobs? I want to work… I’ve always worked. Tell your readers I want a job. I held a job for nine years. And there’s no doubt in my mind that I can do it again. Please, if anybody has a job and would give me a chance I’d take it.. .Tell them I’m no dummy.”

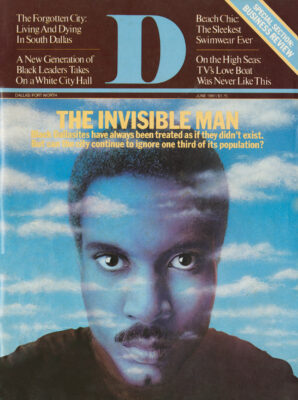

LOU ANN LEE IS NOT WHAT YOU MIGHT CALL A TYPICAL DALLAS ghetto dweller or a typical Dallas black, because, quite simply, there is no such thing. To be sure, she has a lot of things in common with thousands of other Dallas blacks. The fact that she is on food stamps gives her something in common with 53,591 other members of her race in Dallas. (A little more than 17 per cent of the black people in Dallas County are food stamp recipients, compared with about 3 per cent of the white and Hispanic segments of the population.) The fact that she’s unemployed means she has something in common with 23,870 other black adults in Dallas County. (About 8 per cent of the black adults in Dallas are unemployed, compared with about 4 per cent of the whites.) But the only thing that Lou Ann Lee has in commonwith all of the blacks in Dallas is the color of her skin.

They are educated and illiterate. They are rich and impoverished. They are criminals and victims of crimes. They are content and angry. They are as diverse, as factionalized, as socially stratified as their white neighbors across town. Yet they share a common bond that the whites don’t share. When two white people pass each other on a downtown street, they are simply two people passing by. But when two black people pass each other on the same street, they are, despite their economic stations in life, aware that they are two black people. That statement, of course, could be made of any blacks in America. In Dallas, most blacks have something else in common: The vast majority live in South Dallas, a teeming, triangular ghetto that is 13 miles across from east to west and 10 miles deep running from the State Fair grounds to the southern city limits. Driving through the ghetto, a white person can see just what he wants to see, just what he expects to see: men sitting under trees on old car seats, shucking and jiving, drinking Gallo and Thunderbird out of green glass bottles. Driving down the ghetto’s principal arteries-Second Avenue, Illinois Avenue, Hatcher Street, Martin Luther King Boulevard – you can see the type of brightly painted black saloons you knew would be there. The Famous Door, the Righteous Brothers Club (No Loitering), the Hollywood Club, the Paradise Club, the Reunited Club, and – the focal point of Saturday night social life in South Dallas – the Green Parrot Club on Forest Avenue.

But you can also see a lot of things you might not expect to find in South Dallas. There are row upon row of expensive brick houses in the area around Kiest Boulevard and Illinois Avenue. The lawns are trimmed; the flowers are in bloom. The only thingthat distinguishes the neighborhood from Preston Hollow or Richardson is the fact that almost every house has burglar bars on the windows.

The people who live in the $250,000 bungalows have little more in common with people like Lou Ann Lee than Stanley Marcus has with a white sharecropper. The only thing blacks at the two ends of the economic spectrum have in common is that 25 years ago, none of them could have gotten a seat in a downtown restaurant. Most of them still remember that.

THELMA CARTER WASHINGTON LIVES IN A shady, all-black neighborhood in South Oak Cliff. Almost 60, she has lived 38 of her years in Dallas. “I’ve lived all around Texas, and I lived in California a while, and in Kansas, but I always came back to Dallas. It’s like coming home to your mother.”

Mrs. Washington’s love for the city has its practical considerations. “For sure,” she says from the swing on her front porch, “there’s more opportunity here. I can make a better living here and I’ve never worried about crime.”

For Mrs. Washington, work has meant raising her 11 children and holding one, sometimes two jobs in order to support the family, which has not always benefitted from the income of a husband. Currently, Mrs. Washington is married to a truck driver, her third husband. She has converted her garage into a nursery where she keeps children for working mothers for $25 a week and less.

Mrs. Washington and her husband have to take in $1500 a month to cover their expenses, which include supporting two granddaughters.

“These are good times for me,” says Mrs. Washington, “even though I worry about expenses going up so high. But times have been hard in the past. I guess the worst was when I got disabled and couldn’t work for about a year. I didn’t have a husband at the time, so I put the children on welfare. We were living in a house, and all our furniture was repossessed. I asked my kids, ’Do you want to go back to the projects so we can sleep in beds?’ ’No,’ they said, ’we’d rather sleep on the floor.’

“We did live in the projects once,” says Mrs. Washington. “It was after my second husband came home from Korea. While he was gone, I bought a house. But he came home and decided he didn’t like it. So we lived at Frazier Court for five years.”

In 1965, Mrs. Washington became thesecond black person to buy a house in her South Oak Cliff neighborhood. It cost $12,000. “I loved my white neighbors,” she says. “We treated each other like family. The white lady next door used to keep my children while I worked as a cook at the Cabana Hotel. And another lady down the street there, she used to keep my little boy every afternoon after school because she had a son his age and they loved to play together.

“I was sorry to see all the white folks move out, but it’s their choice. And I think that’s something we all ought to have: a choice. If people want to live with their own kind, that’s fine, and if they want to live with a mix, well, that’s fine, too. That’s what bothers me about busing, ittakes the choice away from people.”

Mrs. Washington takes pride in remaining self-sufficient.

“I once had a neighbor,” she recalls, “a white lady who didn’t know how to do anything, not anything. I used to tell her, ’Look, you should go and get a job and do something with yourself.’ But she said she had her husband to support her and, besides, she didn’t know how to do anything. I told her that she wouldn’t have that husband forever, and that she could learn to do something. Well, a year later that husband was dead, and she came to me. ’You were right,’ she said. ’And now I don’t know what to do.’ “

Mrs. Washington took that neighbor’s hand and took the first steps with her. ” ’Now,’ I said, ’your husband has left you social security, so that’s the first thing you do, go get that social security….’

“I’ve learned that it’s all in having an open mind,” says Mrs. Washington of the strength she’s gleaned over the years. “I believe I can do anything I really want to do. For years my mother told me to take up sewing. I didn’t want to, didn’t have time. Well, five years ago, she died and left me her sewing machine. About that time I took in my two granddaughters, because their mother wasn’t interested in raising them. And guess what? I started sewing. Never even took a class. Just started simple, and now I make all their clothes, pantsuits, and everything.”

Mrs. Washington believes that the bestremedy for society’s ills lies within people and their power to help themselves, but she does wish there were more communication between blacks and whites. Her message to the leaders of Dallas? “Get together, and get an understanding. We’re gonna have to reconcile sooner or later, and if you can talk English, you can get together.

“Me, I’m doing just fine. I have my family and my work, and all I want to do is fix up my little house and work in the yard, and live.”

“IN DALLAS,” SAYS 46-YEAR-OLD MARVIN Robinson, “we do just enough to see that people of color are not so deprived as to be belligerent about it, but nothing more.”

Robinson is the administrative service manager for Xerox’s national office products division, but he doesn’t like to dwell on his personal success. Instead, his interests remain focused on the community. He has been a member of the Dallas Parks Board and he has had important positions on city-wide campaigns, like the one to elect Jack Evans mayor.

Robinson believes that racism in Dallas is “subterranean” rather than overt. Almost all major activities in this city, he says -the arts, the government, the institutions-exclude minorities through some mechanism. One or two blacks have been brought in, but no more. “Having served on the boards and commissions in this city, I know that people tend to respond to their peer group,” says Robinson. “We blacks are selectively excluded from the unofficial network of the country clubs and other similar institutions, and as a result, we are only able to address bodies like the city council formally, or we aren’t invited at all.”

Who does Robinson blame for the state of stagnating racial tension in Dallas? “Our black leaders. We have not pushed hard enough in this city for change,” he says.

But things are going to change rapidly around here, Robinson says. “Because of Dallas’ international posture, many of the people who get off planes at D/FW airport will be from Nigeria and similar places,” he says. “They’re not all going tolook like Tony Curtis.”

Robinson sees the plight of the average black man as pretty grim. “When you start talking in terms of employment, you are continually talking about underemployment for black people; when you start talking about housing, you are talking about inadequate housing; and when you are talking about schools, you’re talking about inadequate education,” according to Robinson.

ON FOREST AVENUE, HOLLIE PETERSON, Jr., epitomizes the middle-class black American. Peterson is struggling against what he now considers the inexorable magnetic pull toward downward mobility. His trade is reupholstering and drapes.

Peterson is not content with his lot in life. He’s ambitious, but also realistic, cynical, and irreversibly bitter.

Now 53, Peterson tried to take advantage of every opportunity afforded him bythe VA bill, studied electronics, worked at TI, and eventually started his own business in upholstering “because it didn’t take a lot of capital to get started… all you really need is a tack hammer and a sewing machine.”

Things went like he’d planned at first. Peterson socked away enough profits to buy the Hughes Draperie Co. “in nineteen fifty sumthin’ ” and abdicated South Dallas for the home in the more substantial neighborhood he currently lives in in Oak Cliff.

Peterson was confident he was well on his way to kissing the lower middle-class life good-bye in favor of something better, then found himself hammered on the economic cross of staggering inflation and dwindling credit availability. “I had a lot of plans. Now I don’t know how they’ll turn out,” Peterson says as he warms his lunch, a pan of stew he brought from home, over a burner in the back of his shop.

Peterson feels he knows who’s to blame. It’s the White Establishment. Not the one in Dallas. The one in Washington.

“I’m not a Democrat or a Republican. I’m just a man trying to make a living,” he says. “I hate it that my kids have got to grow up in this situation.

“I’m not content. Hell, no. I’m a long way from that. I’ve been screwed out of two houses by crooked judges downtown. But I don’t feel much less respect for them than I do a bunch of the black pastors in this neighborhood.

“Hell, at this point, it doesn’t matter if you’re white, black, blue, or brown. The rich get richer and so forth. I look into the future and see the biggest kind of… mess.

“And now customers can’t come into my store because of all the junk out there on the sidewalk, piled up by that bunch of bums out there drinking that booze and selling those pills. They vomit on your front door and you’re supposed to clean it up. And if you try to move ’em out, they just throw a brick through your front window.

“Complain to the city and they tell you it’s your responsibility to take care of it. Hell, I don’t work for the City of Dallas. I’m not gonna clean it up.”

The more Hollie Peterson, Jr., talks, the more he sounds like Eddie Chiles.

“The government gives out a bunch of little promises that turn out to be great big old lies. After a while you have to figure that the government is run by crooked lawyers, for the benefit of a bunch of dope addicts on welfare.

“Yeah. Everybody has a promise to make and nobody can fulfill it. They had some people from the White House down here a couple of years ago at the meeting atthe Fairmont Hotel, to register all the suggestions and complaints of small businessmen. I went, but the whole time I was there, I didn’t see any of the White House people even bothering to take notes.

“I applied for an SBA loan, put up 10 grand in collateral, and all I can get off that is $7000. I can’t even buy a van for that.

“Ford builds a swimming pool at the White House and Carter comes along and covers it up. Where does it end?” At this point, the black businessman starts laying down a line of logic that positions him somewhat right of Alexander Haig.

“The pressure is on the middle class,” he says. “People can come into this shop and literally steal whatever they want out of here. And now they’re talking about taking away your guns. There’s gonna be a big, violent struggle coming up and it doesn’t have anything to do with white against black. It’ll just be people fighting for themselves.”

He desperately wishes for a loosening of credit which might lead to the kind of capital it would take for him to meet a payroll.

In the meantime, Peterson must be content in dealing with a lengthening succession of 16-hour workdays.

“Reagan or Carter.. .it don’t matter. I gotta go to work anyway.”

JAMES WASHINGTON’S GOAL IN LIFE IS TO have a quiet little house close to a bus line. Not much to ask, perhaps, but when you’re a career janitor trying to cope with the problems of inflation, it’s certainly not a goal to be considered easily obtainable.

Washington is something of a fixture at KERA-TV, where he’s worked for years. “I feel I’ve been real lucky at Channel 13,” says Washington, “because I’ve done some interesting and unique things. I’ve been on TV, and I’ve met a lot of interesting people. I have a lot of autographs, too – Cheryl Tiegs and Lou Rawls and a whole lot of others.” Washington also has a collection of 200 or so T-shirts, many of which Channel 13 employees have brought him from their vacations. “I have ’em from all over -England and everywhere,” says Washington, who cooks barbecued ribs for up to 200 people at special station events like Juneteenth and the Fourth of July.

But all the T-shirts and goodwill never bought Washington enough financial security to have a permanent home. Around April 1 he received an eviction notice to move from his rented house on Thomas Street. This is happening all over the neighborhood where Washington lives. Old Freedmenstown, between downtown and The Quadrangle, is a once-elegantarea slated for demolition and new construction of high-rise offices and homes. This wave of change sent Washington, his arthritic wife, three of their five daughters, and an eight-month-old grandson to a house in South Dallas. The Washing-tons’ rent went from $134 a month to $325, plus bills. It took Washington’s vacation pay to make the move, and there are added costs as well. The South Dallas location means Washington’s youngestdaughters can no longer walk to North Dallas High School. “Bus fare for three people every day adds up,” says Washington. “1 don’t like what we’ve gotten into over in South Dallas,” he says ruefully, “but it’s all I could find. There’s nothing left in our old neighborhood, and Tram-mell Crow’s bought up Little Mexico, which is the neighborhood closest to my work.”

Washington doesn’t think a lot aboutthe state of affairs in the city, but he does wish someone would do something about the transit system. He rises every morning at 5:15 to catch the bus. And if he misses it, he’s late to work because the route is so thinly scheduled. In the afternoon it can take him two hours to get home.

As for social prejudice, Washington has welcomed the change. “I have people to take me to lunch or something, and I can go in and sit with them, whereas just a few years ago I couldn’t. I think that’s encouraging.”

As for any personal goals, Washington’s wishes are pretty simple. Every afternoon when he gets home he gets himself a drink and puts on Lou Rawls. “Or jazz,” he says, “I like jazz. Now if I can just fixme up a new barbecue pit at the duplex I’ll be in good shape. Oh, I would like to be able to buy myself a ticket to Denver to see my daughter. And my dream is to buy a house out on the edge of the city where there’s a good bus line so I can get to work. But I don’t know when I’m going to get around to that. Right now I’m just worried about my bills. I’m hoping we don’t have another bad winter for a long time… the utilities could just about do me in.”

WILLIAM “BILL” STONER BELIEVES THAT Dallas is about to burn, “that we’re very close to a ’flash point,’ and when it happens, it’s going to be a lot worse than Watts.” He says the atmosphere in the housing projects is so volatile that nearly any incident, “most likely something involving the police,” can, and probably will, set it off.

Stoner lives in the Park South area, an area he describes as “tombstone territory,” where even police fear to tread unless they travel in twos and threes. “Most of the police are thought of as enemies here,” he says. (Blacks there have a saying: “If a white man driving through runs out of gas, he’d better just keep driving anyway.”) “There’s a real siege mentality,” he says. “The only reason they’re here at all is to protect the white businesses. They’re certainly not here to protect the blacks.”

Stoner is black, bright, young, and angry. Ten years ago, he says the media continually referred to him as a “blackmilitant.” Today, he says, he’s called a “community activist,” or a “community leader.”

Nevertheless, it has been the labels that have changed, not Stoner or his philosophy. During the Sixties, when he was working with SNCC or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), his heroes were Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Joan of Arc -“anyone on the front lines.” Today he has added Libya’s Moammar Khadafy to the list.

Stoner is one of the few blacks in Dallas who moves smoothly between the established institutions and what he refers to as “the street people.” Any reporter who has covered either the school board or the city council is familiar with Stoner. He’s atnearly every meeting, and he’s at the microphone.

Asked to describe himself, he says he’s “an organizer, one of the best organizers, if not the best in Dallas.” If the city council wants to raise the bus fares, Stoner is at the microphone giving the mayor another migraine. If the DISD wants to end busing, Stoner is at the desegregation hearings giving hell to witnesses who are testifying the wrong way. If there is a rent strike somewhere, or a protest, or a problem at the Martin Luther King Center, Stoner is there.

Stoner is as close to a “street radical” as one is likely to find in Dallas, of the genealogy of H. Rap Brown and Stokeley Carmichael. Neither Stoner nor his message has mellowed, and without question, he is closer to the poor people of the projects (“the people who riot”) than the more establishment blacks in the city.

“Established organizations don’t really have any control over street people,” he says. “Look at the riots in Miami. The ’black leaders’ were shouted down. When rebellion happens, it is the street people who will be in the street. Dallas doesn’t even understand the mechanics of what is going on.”

Stoner is completely distrustful of “the system” in Dallas. He says the city is “masterful at public relations, at putting out the word about what a great city Dallas is, that there are no problems. They point to the Martin Luther King Centerand say, ’Hey, look what we’re doing for our niggers over here.’ “

Stoner says that Dallas “is one of the most segregated cities in the country. It is most blatant in terms of housing. Blacks never see houses a block long on Royal Lane. It’s two different worlds.”

Asked why he continues to show up at city council and other public meetings if he so distrusts those institutions, Stoner replies, “I ask myself the same question every time I go. I guess the answer 1 give is that we’re giving them one more chance. They can’t say we didn’t warn them. This city is going to explode.”

MARVIN CRENSHAW LAST YEAR FOUGHT a good fight against city hall and, of course, lost. It was Crenshaw who headed up the effort to establish a police civilian review board in Dallas with investigative and subpoena power. He ended up with the Police Advisory Committee, a kind of toothless compromise that neither he nor his cohorts are buying.

In fact, Crenshaw is preparing to go back to the council and, if necessary, back to the voters in a referendum to achieve his original goal.

Crenshaw is a well-educated, well-spoken young man who speaks in a quiet, modulated voice that belies the anger his words betray over the treatment of blacks in this city. “Dallas is a very racist city,” Crenshaw says, pointing out how difficult it is for blacks, to do such simple things as cash a check or get an auto burglary investigated promptly.

Crenshaw believes that “an explosion in the street is always a possibility, but we have to ask, do we want a riot or do we want to build a political structure?”

Crenshaw clearly wants to do the latter. “What we are seeing is a change in leadership in the black community. We’ve always been divided, but now the point is to achieve some sort of political power and representation.”

Like so many other blacks interviewed in South Dallas, Crenshaw believes the victory in the recent city council election of Elsie Faye Heggins over the perceived “establishment candidate,” Mabel White, was portentous. “Elsie Faye was much more in touch with the people,” he says, “and it is the people who will have the ultimate power.”

Crenshaw believes that “even the white power structure here is receptive to new black leadership – even if they don’t always vote with the establishment.

“Much of the new leadership in this city will come out of the black community and out of the political process.” He points to John Wiley Price as an example of an “electable” black who cuts across bothblack and white power bases.

Perhaps ironically, Crenshaw believes that many of the cutbacks in social services that Reagan is proposing “actually will be good for the black community because it will get us doing things for ourselves, instead of depending on someone else.”

BILLY ALLEN, OWNER OF MINORITY Search, one of a handful of black employment agencies in Dallas, sits back in his South Dallas office, sighs, and launches into what he calls a tired tale about his business. Allen, 36, worked in sales and marketing before starting his firm. He is married, has two children, and lives in Oak Cliff.

“It’s an age-old problem,” says Allen. “It hasn’t changed. They just don’t call on Minority Search. I started this business in response to market comments that if we could find qualified minorities they would hire them,” Allen says. “Six years ago, when I was new, I anticipated that by now I would have three other offices in Dallas. The demands have just not come through. If you would listen to conversation you would think our phone would be ringing off the wall, but it’s just not happening.

“It has always been better in other cities,” Allen contends. “We in Dallas are behind the rest of the country by 15 years.”

Allen says that blacks are making little progress in the corporate suites, and the number of jobs in those suites is increasing in Dallas. “That means there are fewer and fewer blacks as a percentage at the higher echelons.”

He says there are only a handful of blacks in Dallas who have jobs high enough in the major corporations who have hiring and firing authority and who can spend money without getting approval from higher-ups.

Allen believes that getting those top corporate jobs will come when a few more blacks get hired at key positions and they, in turn, hire more blacks. “Until we get people in those positions,” Allen says, “we are going to have a difficult time convincing majority businessmen we should be given job opportunities and business opportunities.”

He says that blacks have the easiest time getting sales jobs. He gets about five inquiries a month from major businesses and corporations but has five inquiries a day from qualified blacks who want jobs.Of those seeking jobs, 95 per cent have college degrees and 20 per cent have advanced degrees.

“It’s at a standstill from my vantage point, which is employment,” Allen says. “The gap between black and white employment is widening. When you are looking at people who are moving into decision-making positions, there are fewer blacks, and others are moving into those key decision-making roles.”

He thinks the problem with employment of Dallas’ blacks stems from a larger problem of racism in the city.

“I don’t think we have open, name-calling racism. I don’t think anybody would call you a vulgar name. There aren’t any racial slurs directed at individuals here. But in terms of what happens, this is a very racially separate community.

“We don’t have the kinds of jobs that would allow us to purchase houses in exclusive neighborhoods. I feel discriminated against from a business standpoint. I know I am subjected to a lot of discrimination. If you make the money in Dallas, you can pretty much do what you want to do. You tend to lose your skin color, if you have enough capital.”

Allen says that the relatively corruptionfree city administration has appeased blacks because they can expect reasonably good city services from garbage collection to police protection. But he thinks the passivity of blacks in Dallas does not come because blacks are satisfied. Rather, it is because “a lack of programs over the years has convinced a majority of black folk we cannot make any satisfactory gains short of violent confrontation, and black folk don’t want violent confrontation, so they go along and get along.

“Black leaders have been unable to fulfill promises they have made to constituents,” Allen says. “So there are fewer black individuals who want to participate in the process. The real danger of undermining the moderate black leadership is that if there is a Miami or a Detroit or a Watts in Dallas there would be no peacemakers, and that’s a real danger.”

MERRELL BOATLEY KNOWS EXACTLY what he wants in life: an executive job and a lakefront home. Boatley is an assistant manager of the Burger King on Mockingbird Lane at McMillan, a job that requires him to work many late nights. He is married, with one child, and lives in an integrated Centennial Homes subdivision inGarland.

“I’ve lived in Dallas all my life,” says Boatley, “and I can’t believe the change. Right now I’m noticing all the building that’s going on downtown. We’re growing at an unbelievable rate.”

Boatley worries about the crime rate that’s growing along with Dallas. “I’ve never had any problems personally, but I don’t think the Dallas police are patrolling the neighborhoods like they should.”

But time and change have also brought about improvements for blacks in Dallas, and Boatley thinks the changes are long overdue. “I’ve had to go through the back door to get something to eat and sit in the balcony at the movie house,” he recalls, “and that seems like a different world from today. Oh, things aren’t perfect, they never will be, but had it not been for the civil rights movement, I’d hate to think where we’d be today.”

JESSIE HORN WOULD MAKE A GOOD spokesman for the Dallas Chamber of Commerce. “I know that Dallas is the best place in the world to work in,” says Horn, 54. “There are plenty of opportunities here.”

Horn, a native of Dallas, does yardworkand other odd jobs in an area that stretches from East Dallas to Love Field, unless his pickup truck isn’t working. (“It’s up and it’s down,” says Horn.) Work is steady during the warm-weather months. It slacks off in winter, when Horn is hard pressed to find indoor jobs to keep him paying $27-a-week rent for his apartment on State Street, near downtown.

Even though Horn seldom has trouble finding work, he is concerned that not all blacks in Dallas are so lucky. “I know quite a few that’s been laid off,” he says, “and it bothers me. I don’t know when it’s gonna get better. I think part of the problem is that we have too many foreigners coming in and taking jobs away from colored folks. Used to be that there weren’t any Mexicans working for the city, and now there’s a whole bunch.”

Horn votes in presidential elections, but doesn’t keep much of an eye on city politics. “I don’t have any complaints about the mayors and the others who run Dallas. I liked Folsom okay, and I think the new mayor will be alright. When it comes to the city, I have one complaint: garbage. I mean, the pickup service is the worst I’ve ever seen in my whole life. They won’t pick up nothing.”

But this is one of Horn’s few complaints about life in Dallas and life in general. “We’ve got a rich lady in our neighborhood,” he says. “She’s a millionaire. She owns her own home, has five or six rent houses, and gets a new car every year. And of course there are a lot of rich white folks in Dallas. But I never felt that a rich man is happy. I think a poorer man is happier. And I know one thing -a rich man is tighter than a poor man. That’s how hegot rich,” he says laughing.

CLYDE CLARK IS THE CONSUMMATE EXAM-ple of a black who has worked within the system -and for whom the system has worked.

Born 37 years ago in Dallas, and a graduate of James Madison High School where he was student body president, Clark has always been at the head of his class. His resume reads like an honor rollof achievements, and includes such distinctions as former vice chairman of the Dallas Alliance, former president of the NAACP Youth Council, former regional vice president of the National Business League, and chairman of the Board of Deacons of the Mount Carmel Baptist Church.

Clark has served on two presidential boards -the Private Industry Council under President Carter and the Policy and Review Board under President Ford. When Wes Wise was mayor, he presented Clark with the key to the city in recognition of his service to the community.

When asked what he’s done for Dallas lately, Clark says he “recently negotiated the bus strike settlement and, of course, I’ve been active in the school desegregation case.”

While Clark is reluctant to take personal credit, he put himself on the front lines in the black coalition to maximize education’s decision to split with the NAACP by opposing further forced busing in Dallas. One gathers that courage is a key component of Clyde Clark’s personality, and while he obviously has swum well in the mainstream of the Dallas community, he is still a tough, independent, and responsible black voice worth listening to.

But if Clark has been good for Dallas, it is equally true that Dallas has been good to Clark.

He owns three businesses here, including Commercial Truck and Trailer, of which Clark is president, Gifty Cosmet-iques, which his wife Gifty runs, and Lone Star Trucking, headed by his father.

Not surprisingly, Clark is optimistic about the role blacks can play in the future development of Dallas: “The key to destroying the ghetto,” he says, “is totally based on economics. In the Sixties and Seventies, we fought to break down barriers. Our key to salvation is to enter the economic mainstream. No other area is as receptive to that as is Dallas.

“Dallas is going to be good for our people because the leadership of this city realizes that if Dallas is to continue to thrive it must remain calm. Our leadership is willing to work with us toward that end.”

CINCY POWELL, FORMER AMERICAN Basketball Association all-star, is standing before a television camera in the foyer of his Oak Cliff restaurant, the Peach Basket, waxing eloquently and bullishly about business opportunities in Dallas.

“This is a friendly town,” he tells the interviewer making a recruiting film for the-Dallas Mavericks. “People speak to you on the street. And there isn’t any opportunity anywhere in the country that youcan’t find in Dallas.”

This pitch is not something Powell made up for the Mavericks. He firmly believes Dallas is a “free enterprise city” for blacks as well as whites, and if blacks aren’t making it here, it’s their own fault.

“There isn’t anybody in Dallas who is any poorer than I was when I was growing up in Baton Rouge,” Powell says. “1 have no sympathy for people who rely on gifts from others to survive. I lived here in 1968 when I was playing for the Dallas Chaparrals. And I saw Dallas at the time when it was into its racial thing. All that’s water under the bridge.”

Powell says his restaurant business is an example of how Dallas can work for blacks. “It wasn’t easy to get it off the ground, but then no business is. I was undercapitalized. I had the promise of cash that didn’t materialize. I had all the problems and I survived.”

Powell takes issue with other black business leaders in Dallas who say that the deck is stacked against them. “There is a certain animosity between the established blacks and the new blacks coming in. Aggressive blacks are coming in here every day. They’re getting jobs and starting businesses. The outsiders are coming fromwhere they had to fight and hustle for their deals, and they are successful because they don’t sit around and bellyache.

“Talk to anyone. Talk to Bobby Fol-som,” Powell says. “He made it and he’ll tell you it wasn’t easy. And he’s white. People who play by the rules should be rewarded.”

And the rules are the same in Dallas, Powell says, for blacks and whites. All the blacks need to do is get in and play.

Related Articles

Basketball

Watch Out, People. The Wings Had a Great Draft.

Rookie Jacy Sheldon will D up on Caitlin Clark in the team's one preseason game in Arlington.

By Dorothy Gentry

Local News

Leading Off (4/18/24)

Your Thursday Leading Off is tardy to the party, thanks to some technical difficulties.

Arts & Entertainment

Curve Ball: Local Shorts Highlight Diverse USA Film Festival Slate

A college freshman spotlights his high school pitching coach’s unique baseball story in his filmmaking debut.

By Todd Jorgenson