THE FIRST funeral I remember was my Uncle Boyd’s on December 23, 1939-a date I’m sure of because it was my sixth birthday. Boyd himself is a shadowy figure, a tall laughing ghost from the family album. He died violently at 24, stabbed at night in a country schoolhouse, and two vivid images from his death haunt me.

My mother and I are standing outside my grandmother’s house in a cold, gray rain. She is crying and clutching my left hand, pulling me up awkwardly to her tall side. With my free hand I try to protect the shiny plush collar of my new winter coat from the steady rain. I’m crying, too – whether for my uncle or my collar I no longer know, if I ever did.

Then we are in my grandmother’s parlor, a formal room usually kept clean and closed against the Mississippi weather. A long shiny box dominates the room, and behind me I hear sighs and the words, “… so tall they had to send clear to Memphis,” then a sudden hush. In the box, my mother whispers, is your uncle. Look, she says. Say good-bye. I look in the box at a dark blue suit, a tie, folded hands, a cold, gray face on a shiny pillow. 1 know one thing: It’s not my uncle, that’s for sure.

I’ve been thinking a lot about funerals lately; I don’t know why. Maybe because it’s spring and a sort of natural human perversity, a craving for opposites, makes me think of death in spring, of life in winter. Or maybe because my 79-year-old father, shortly before he had open-heart surgery in March, confided to my mother that when he dies, he wants a big funeral with lots of people there. She told my brother Ken and me about it as evidence of his morbidity, but we both smiled, struck at once with the humorous discrepancy between this ambition and the modesty and self-deprecation of his entire life.

Now, in retrospect, interest in one’s own funeral impresses me as normal and wise. My father is doing just fine, thank you, and I trust he’s got at least the 15 years left of his father, who died at 94. I hope he has more. But when he goes, I want to be around to give him the send-off he deserves. If it were appropriate for a Southern Baptist deacon, I’d see to it he got “a perfect death,” which an old-time jazz musician once described in this fashion:

It was pretty, all right, to see those funerals. A man belong to one of the organizations and die, his widow say “let him have music” so the organization hire a marching band. On the way out to the cemetery, before they bury the man, the band played most all hymns, “Just a Closer Walk with Thee.” But once they left there, then they started to swing. Then they’d play “Sing On” or “The Saints.” Everybody else would be bouncing along, too, some with baskets of flowers… That was always the end of a perfect death.

But my father is not a dancing man, and although the dignified walk to the cemetery might be to his liking, I’m afraid the black man’s “strut,” the celebratory return, might offend the sobriety and rectitude of his white shade. To each his own, after all, in death as in life.

What my father and I share, because we both came of age in the same kind of large family and the same small town, is a sense of the closeness, the familiarity of death. City-bred children, products of nuclear families, rarely develop this sense, I think. Familiar with street slaughter from the papers and celluloid murders on television, they are shockingly inexperienced with natural death as an ordinary part of life. Many of my students over the years have volunteered that they have “never seen a dead person,” and my own two children, now almost adult, have attended only one funeral, that of their paternal grandmother. Small wonder that they weren’t sure what was required – my daughter was dismayed that her brother didn’t cry, my son contemptuous that she did.

In small towns, things are not, or certainly used not to be, so uncertain. To bury my Uncle Boyd, we had to walk less than a quarter of a mile down the road to the Pittsboro cemetery. My flighty memory has lost the burial, but I grew up with his tombstone, with all the tombstones in a community of dead that backed up to my grandmother’s pasture. Summer afternoons I would climb the barbed wire fence and wander barefoot among them. Don’t step on a grave – the Confederate soldiers, the marble lady, the little boy with his and his dog’s picture (Had the dog been buried with him, I wondered?), the man in the above-ground crypt with a crevice I peered into vainly for a sight of bones, my own Reid and Harlan relatives, and almost always, the fresh grave with its cover of damp red clay and its circle of flowers.

By the time I was 13 or so, an age when girls, no matter how tone-deaf, have “sweet voices,” I had probably sung “In the Sweet Bye and Bye” or “Whispering Hope” in the funeral choir at either the Methodist or Baptist church for the sleeper in the fresh grave. People died at home, in the presence of family and friends. We “sat up with the body”-my cousin and I sat all night in the room with my dead grandmother. The whole town turned out for a funeral. Only a smalltown boy like Mark Twain could think of the glorious coup of letting Tom Sawyer get home in time to attend his own funeral. From nearly every house someone came eventually to take up a cemetery abode. How could the sign outside town continue to read pittsboro, pop. I90? The dead must count, too, I decided.

At a lugubrious 16, I discovered the equally lugubrious Romantic poets, and death became more mysterious and beautiful to me. At the back of the Pittsboro cemetery was a dank little pond, its black water full of the needles of the big pines that shaded it. I sat there welcoming melancholy and brooding on Keats, dead at 26; on Byron, a martyr at 36; on Shelley, the ethereal spirit who drowned at 30. These delicious deaths had little in common with that of old Mr. Sam Ellard, who simply disappeared one day from his sunny spot on the courthouse square and showed up in the cemetery two days later. In Pittsboro, people died when they were supposed to.

These deaths were, I imagine, similar to what Philippe Aries would call in his book, The Hour of Our Death, “tame deaths.” Death was predicted, accepted. One died in the bosom of the town. When my second cousin Miss Lou Ligon died of breast cancer, she was at home. The women went in and sat with her that afternoon with their needlework. They came out pale and sad, but when she died, her funeral, like all our funerals, became an occasion for reaffirmation of faith. Our world was whole; death was evil, but we would meet again in heaven. Souls were often “brought to the Lord” at a funeral. Such deaths characterized the Middle Ages, Aries says, confirming my suspicion that the rural South was, several decades ago, still a medieval society.

Aries claims the romantic obsession I had with Keats and company is typical of a 19th-century model, “the death of the other,” in which death is “moving and beautiful like nature.” A death was no longer a calculated subtraction from an entire community, but a personal and wrenching loss. The death itself was often highly dramatic. Keats sat up in bed and coughed blood, then died peacefully. Byron died, surrounded by fools, bled by blundering doctors, of a fever at Mis-solonghi in the war for Greek independence. Shelley drowned, not in the sea of bathos I immersed him in in my imagination, but in a literal sea, and got the best funeral I’d ever heard of. Being cremated on the seashore by a group of his friends, his body was almost consumed when they noticed his heart would not burn. One of them reached into the fire and pulled it out, burning himself badly. In the poet’s heart I recognized a symbol that put singing “Whispering Hope” to shame. When death took my own first “other,” however, it was not romantic and stirring.

At 19, I was complacent. Old people really died, young people only in books. The boys in town had been to Korea and come back safely, with Chinese pajamas to show how far they’d been. After that, what was there to fear? Then my brother Sonny, 16, was killed in a freak accident, and poetry became reality. Through his death I knew in my bones what John Donne meant when he wrote, “Each man’s death diminishes me.” I was diminished; beyond that, I was afraid. My brother, who had loved Ring Lardner and baseball, was dead. His thin face and comical crew cut, his arms and back strong and brown from working outdoors, his flashing sardonic grin, were not in the cemetery under the big new tombstone, they were gone. And I could go, too, just like that. Suddenly, neither time nor kin nor God, nothing, stood between me and death. The funeral was a travesty in my eyes. What did Sonny, just learning to drive, have to do with whispering hope and the sweet bye and bye? I would have to live in this shadow, in the shadow of this fear.

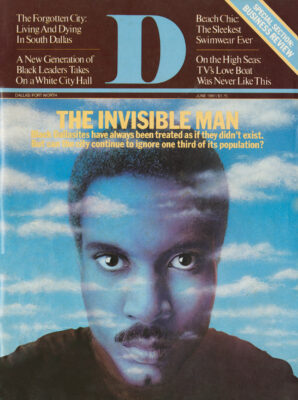

Aries would perhaps declare that, skipping through history, I had hit the 20th-century attitude on my own. During the course of this century, Aries claims, fear of death has led Western man light-years away from the “tame death” to what he terms the “invisible death.” Lacking a communal faith that enables us to accept the end of life, we lie to the dying and force them to lie to themselves and to us; death becomes, as sex was to the Victorians, the obscenity that cannot be mentioned. So that the lie is easier for us all, and for practical reasons as well, we send them to hospitals merely to die, often as undignified things with tubes coming out of every orifice. Because of the “medicali-zation” of death, as Aries calls it, death is not an instant; instead, the time of death has been lengthened and categorized into brain death, biological death, cellular death. Once all the little deaths cohere sufficiently to produce the legal state termed death, frequently reached in isolation, and the medically-induced coma that replaces despair or hope, the dead person must be collected and funeral arrangements made.

But what sort of funeral rites can be arranged for someone who dies in a sanitized vacuum, by bereaved who were probably not present? Aries’ statistics are revelatory: In a 1963 study, only a quarter of the bereaved were present at the death; only a third believed in an afterlife. The short walk to the cemetery, songs of heaven, souls saved at the funeral, and other vestiges of a united community facing death would be anachronistic, even absurd, under the circumstances. To anyone familiar with the current respect for technology and specialization, the solution is simple. As the still-living body was turned over to those experts, the doctors, the now-dead body can with relief be submitted to those other experts, the funeral directors or morticians.

Funeral directors have often been attacked, most notably by Jessica Mitford in her 1963 exposé, The American Way of Death. Mitford explores brilliantly the unscrupulous practices in the United States that result in funerals unequaled for expense, display, and superstitious mumbo jumbo. I have no doubt such exploitation exists in Dallas as elsewhere, but I want to make another point: Many of us cannot cope with the emotional reality of death and its effect on the meaning of life. Having cast our traditions aside during our uprooted and noncommunal lives, when death strikes we have no fragments to shore against our ruin. We welcome the services of someone who can suavely and instantly provide us with socially acceptable rituals, however remote those rituals may seem to the experience of our ordinary world.

Reasonably enough, the funeral direc-tor seeks to fill the gap. For the thousands of people who, like my father, will die in the heart of a fervent faith, the funeral director is really only a convenience. For a fee, he can file the requisite permits and papers, provide the coffin, embalm the body if desired, arrange transportation and burial service. For the other thousands who die outside a community of believers, the funeral director is ready to provide more. Exactly what is needed, what do people want from funeral directors in Dallas? I found the two funeral directors I talked to philosophical, articulate, and surprisingly candid.

“Grief shared is grief diminished,” says Ben Coleman, manager at Ed C. Smith and Bro., Inc., which after 105 years is probably Dallas’ oldest funeral home. “I believe in heaven and hell, myself, but I think any funeral service should gently take a person by the shoulder and force him to face death. Lots of times you see grown children trying to protect an aged widow by making decisions for her, but she needs to participate-it’s therapy for her. And it’s good to have reminders of one’s own death.”

Coleman went on to say that, in his opinion, children should come to funerals and be told the truth about death. “Don’t tell them, ’Grandmother is asleep.’ The child will expect her to wake up in eight hours. That old ’Asleep in Jesus’ line you see on tombstones is confusing to children. And don’t say, ’Jesus took her.’ The child will think, ’Bad Jesus.’ Use the word ’death.’ Explain the process of life and death. Let the child cry and grieve, but don’t force him.”

Ronald Hughes at Dudley M. Hughes Funeral Homes (“Three Generations of Service-From Our Family to Yours” in the Yellow Pages) makes essentially the same point. “A lot of people don’t want to think about death or talk about death because it might happen. My own father was that way, even though he was in the business – he never did see a casket he wanted.”

As a contrast, Hughes describes one of his own clients. “There was this wealthy man who bought his casket 10 or 15 years before he died. It was a gorgeous casket, very expensive, silver-plated copper. He used to come by pretty often to see it, and once or twice he even called up in the middle of the night, after a party, you know, to ask if he could bring some of his friends over and show them his casket. We always opened up and let him come-he was really proud of it.

“But most people want the traditions they grew up with, the same things for their relatives that are always done, and the traditional element of the community will nearly always want the casket opened.”

Both Coleman and Hughes emphasize that, though an authorized cemetery is required by law, embalming isn’t. “Embalming is no big deal,” Hughes remarks. “It just prolongs the time that can be taken for the service, lets people come in from out of town, and so on, before the body begins to deteriorate.” Nor is a copper or steel coffin necessary, though an elaborate box may escalate the funeral costs considerably.

The average funeral costs around $2500 with a cemetery plot, says Hughes, “though you can get out for as little as $1500 with a wooden casket, even with embalming and a chapel service.” “Direct” or “immediate” disposal-picking up the body, cremating it, and burying the ashes – can cost less than $500, though very fewpeople choose that method. “People ingeneral recognize value and cost, and theyget what they want,” says Hughes. “Thepicture of the grieving widow fleeced bysharp operators is just not valid.”

“One way to look at it,” Ben Coleman volunteers, “is to bury a person in keeping with the way he lived. Did he drive a Volkswagen or a Lincoln Continental? Where did he put his time and his effort? What did he achieve? After all, a funeral service should be a celebration of a person’s entire life. It’s another rite of passage, like birth, graduation, marriage – all the important events.”

I want to believe that, I suppose. One part of me longs to view death as Henry James did on his death bed: “Here it is at last, the distinguished thing.” If I could feel like that, I could probably live a lot more fully, too. It would be nice never having to hedge my bets.

But the truth is, to me death spells a pretty dreary finale to the glory of life, and the funerals in my experience have never seemed adequate to the genius of particular human beings. I think of the memorial service for teacher and writer Lon Tinkle in SMU’s Perkins Chapel, from which I may be buried one of these years. Lon’s son spoke; we had music. Willis Tate, the president of SMU for most of the years Lon was there, talked about Lon’s contributions and his life. Writers, professors, students, businessmen, and literary people thronged the small chapel and talked outside afterward. But something was missing: the florid, courtly, humorous, humane, pragmatic, and persuasive presence of Lon himself, who knew so well how to delight the public eye.

Or take last winter’s service at Highland Park United Methodist Church for George Skibine, artistic director of the Dallas Ballet. The organ played the Romantic music George had loved. The weeping or grave-faced dancers lined the rows and aisles in black dresses and dark suits, looking so much smaller and more vulnerable, so much more mortal, than they ever look on stage. One of George’s twin sons spoke, then a member of the board had more words. Suddenly it occurred to me how futile even the best words were to express the spirit of a man whose whole life had been dedicated to the elegance of precise action.

Now, recollecting this impasse, I shakemyself: I am through with eschatology fora while. I think I will go out and sit inthe sun.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman