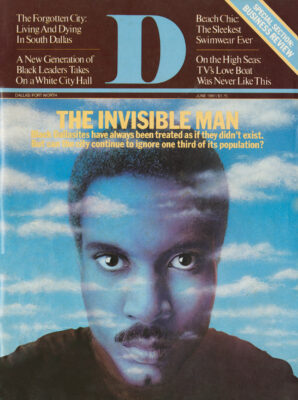

BLACK DALLAS: ANOTHER COUNTRY

BY VIRTUE of his skin pigmentation, the average black Dallasite’s life will be 11 years shorter than that of his white counterpart. Perhaps in some ways that’s a blessing, because during his 55-year life-span, he will be three times more likely to be arrested, four times as likely to go to prison if arrested, and roughly eight times as likely to end up on welfare as the average white resident.

The disadvantage of being black starts at the beginning of the Dallasite’s life and follows him to his grave. A black infant is almost twice as likely to be stillborn as a white infant. The black baby is 3.6 times as likely to be born to a mother who is 18 or younger, and five times as likely to be born to an unwed mother. The black child is three and a half times more likely to be murdered before he reaches 25. (Murder is the leading cause of death for Dallas blacks aged 24 and under, accounting for almost one third of the deaths of blacks in that age group.) If the black Dallas baby makes it to that golden age of 55, he will have earned about 40 per cent less than his white counterpart. Being black, despite all the civil rights laws and other strides that racial minorities have made in the last 20 years, is still a distinct disadvantage in Dallas.

But the dismal data that one can obtain from the U.S. Census Bureau or the North Central Texas Council of Governments or any of the other agencies that put quantitative measurements on the quality of human life in this county only reveal one dimension of what it is to be black and live in Dallas. The data, the type of statistics you’ve seen a dozen times before in your daily newspapers, simply reinforce our white stereotypes of blacks: poor, under-educated, and violent. We think that’s much too shallow an understanding to have of a race of people who make up one third of our community. If black Dallas were a city unto itself, it would be the seventh largest city in the state, ranking in size between Austin and Corpus Christi.

In many ways, of course, black Dallas is a city unto itself. Physically separated by the Trinity River and a couple of freeways, the black community is another world. It is a world that is five miles and five light years away from the heart of the white Dallas community. It is a world that the vast majority of the 550,000 whites who live in Dallas have never laid eyes upon. And both races have lost something as a result of that.

The racial problem is not that Dallas is a racist city. 1 truly do not believe that it is. Sure, we’ve got an old South heritage of separatism that dates back to the Civil War. Twenty-five years ago, a black person would be hard pressed to find a place downtown where he could use the rest-room or try on clothing in a department store. But the years have done a lot to change all that. Dallas is a city which prides itself on being a city of opportunity-for all of its citizens. The real problem is that most white Dallasites simply don’t know much about their black neighbors. We characterize the black community as a forboding ghetto, a dangerous place which is not to be driven through at night, or at all if possible. The black community is, for most Dallasites,literally out of sight and out of mind.

The demographic makeup of the D Magazine readership gives us a unique opportunity to do something about that. You, our readers, are white by an overwhelming majority. The vast majority of you live in North Dallas. You are ultra-affluent. You are opinion leaders and decision makers. And, by virtue of the fact that you are reading this magazine, we think you have a commitment to be informed about the issues facing this city. (An opinion poll conducted by our staff this month shows that the majority of both blacks and whites in Dallas think race will be an issue in the city during the Eighties.)

That’s why we sent a team of reporters across the Trinity and into Fair Park to discover black Dallas, to experience black culture, to talk to its leaders, its losers, and the average man on the ghetto street. We assigned a team of reporters headed by Associate Editor Mike Shropshire and including Contributing Editors Bill Bancroft, Carol Edgar, and Mary Candace Evans to try to construct a verbal picture of the ideological tapestry of men and women who constitute the city’s black community. To cover the political front, we assigned Associate Editor Steve Kenny to do a profile of black city council member Elsie Faye Heggins and report on the impact that Mrs. Heggins’ aggressive political posture has had on the black community in its struggle for power. And, realizing that a report on the black community written by an all-white team of journalists lacks something in credibility, we commissioned a black reporter, Gale Horton Chery of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, to interview a cross section of the black community ranging from the top of the economic stratum to the bottom.

What they discovered was, in some ways, quite predictable. The physical community that most black Dallasites call home is, on its face, dismal and depressing. It is the land of abandoned cars and half-burned houses. It is a city in which development seems to have been halted in the Thirties. You can drive for miles without seeing a Sanger Harris or a Joske’s, a brightly decorated shopping center, or any of the other material symbols we whites associate with affluence and success. As Shropshire reported: “It looks like they must be expecting a hurricane in South Dallas, because everywhere you look, store windows are covered with plywood.”

Our reporters found anger and frustration, hopelessness and rage. They found people who simply would not talk to them because they are white.

But they also discovered South Dallas to be a place where one can find optimism and resourcefulness, dignity and pride. Black Dallas, in many ways, has a stronger sense of community than white Dallas. Churches are ubiquitous. And there is, among both the optimists and the pessimists in the ghetto, a strongly developed sense of survival. It’s a street-savvy desire for success that can only serve to make the black Dallasite a formidable force in the ongoing struggle to determine just who are the “haves” and who are the “have-nots” of this community.

They discovered a new dedication by the black Dallasite to no longer stay in his “place,” but at the same time they found the black Dallasite not to be consumed by the hatred and the polarization that characterized the Sixties. And they found that the hopes, the dreams, the goals, and the aspirations of the black Dallasite are not that different from those of his white neighbors across town. For a full report of what our journalistic search party found in South Dallas, turn to page 93.

FURTHER SOUTH

BUT ALL our journalistic efforts this month weren’t nearly as sublime as the black Dallas project. While several staff members were perusing the close-to-home streets of South Dallas, others were meandering down the cobblestoned pathways of Isla Mujeres, a tiny island near Cancun, off Mexico’s Yucatan coast. This marks the first time D Magazine has ever left the country to shoot a fashion feature, and needless to say, we’re quite pleased with the photographs we ultimately got. But they didn’t come without some foul-ups, confusion, and near catastrophes. You can imagine how ridiculously vulnerable a crew of nine people can look in a relatively rugged foreign country with thousands of dollars worth of photographic equipment and two teenage female fashion models – wearing revealing bathing suits – in tow.

According to the delirious stream-of-consciousness reports I got, it’s hard to tell which part of the trip was the worst. On the first day, while photographer Charles Ford, assistant Greg Heiberg, art director Fred Woodward, stylist Jan Jones, make-up artist Cindy Gregg, and writer Amy Cunningham were scouting for suitable shooting locations, all three models, who were strictly instructed not to get sunburned, fell asleep in the sun and did just that. Male model Rich Comeau then defaced his otherwise photogenic face by scraping the bridge of his nose along the bottom of a swimming pool.

The photography session on the beach that evening was the kind of disaster of which photographers’ nightmares are made. Seventeen-year-old model Kati Baker fainted from heatstroke and sun poisoning just after the first test Polaroids were pulled, and she had to be helped out of the water by Comeau and model Ly-nette Walden.

The next morning, our slightly discouraged crew was up at 3:00 a.m. in order to catch a 5:00 a.m. ferry from Cancun to the island. Last-minute makeup touches were made as the boat swept from side to side and as makeup artist Cindy Gregg side-stepped the debris and sea spray that sloshed around near the shooting site. Once on the island, the crew’s actions were closely monitored by American tourists and Mexican fishing people. One person wanted to buy a model’s autograph. Another wanted to buy a model.

The chicken enchiladas they ate that day got mixed reviews: Some say they were the worst enchiladas they’d ever eaten; others maintain that they were the worst enchiladas anybody ever ate. In any case, they all got sick, missed the last ferry back to Cancun that night, and chartered a boat owned by a seaman identified only as “Oscar.” Guided by the stars and a tiny flashlight, our band of innocents crawled into Oscar’s fishing skiff with some assistance from Oscar’s muscular friend, George. As you might expect, Oscar tried to over-charge them at the pier in Cancun, and when an unusually stalwart Amy Cunningham refused to pay up, George and Oscar stole a $500 makeup case away from the rest of the cargo and held it as ransom. There was some scuffling around a taxi-cab, the exchange of many disparaging remarks, and ultimately a pretty spooky attempt to stab our beloved art director. “I would have run away,” says Woodward, “but I was wearing flip-flops.”

Thankfully, they all came home safe,sound, and still sick, but alive and withphotographs. The pictures in this issuewere labors of love and anguish: the stuffof which the best photographs are alwaysmade.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.