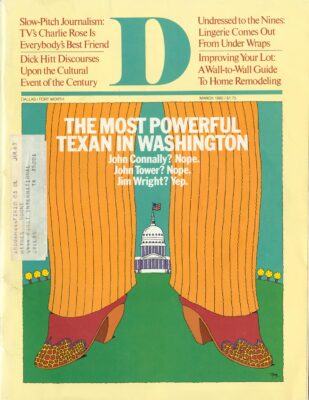

The Deal seemed too difficult to pull off, even for the best deal maker on Capitol Hill. There simply weren’t enough millions to go around. Which meant that somebody had to be the loser. And Jim Wright knew what else that meant: The loser would be one more unhappy millionaire who felt the Congressman had let him down.

So once again, Wright had to do what the people of his Fort Worth district have come to expect from him on a regular basis: Perform the impossible. Get blood from a stone. Get Fort Worth not just its fair share of Uncle Sam’s dollar but somebody else’s share as well.

It hadn’t seemed like it would create that much of a problem when the Woodbine Development Corporation, builder of the Hyatt Regency Dallas, applied for a federal Urban Development Action Grant to pay $6 million for an underground parking garage to be constructed in connection with a $32.6-million privately financed project to turn the old Texas Hotel into a new Hyatt Regency Fort Worth. The parking garage would benefit not only the hotel but the nearby Tarrant County Convention Center. And the federal government would be putting another $6 million into the redevelopment of downtown Fort Worth. That should make everyone happy.

Except Sid Bass. The Fort Worth millionaire was in the process of building his own 500-room hotel at the other end of the street from the Woodbine project. And there was an application in the works with the Department of Housing and Urban Development tor another Urban Development Action Grant for $3 million to be used to redevelop Main Street in front of the Bass hotel. The previous summer it had apparently dawned on Bass that if the Woodbine project got its federal millions and his own project didn’t, the Hyatt would be able to pass its savings along to customers in the form of cheaper room rates.

That’s when all hell broke loose. Doubtless one of the visceral reasons for Bass’ concern was that the Woodbine Corporation is headed by Ray Hunt – of Dallas. Surely somebody from the wrong end of the turnpike was not going to be allowed to get an advantage in a business deal in downtown Fort Worth. Since the people of Fort Worth have felt for years that it is their Congressman’s duty to see that the wheels of government turn their way, this immediately became a job for Jim Wright.

The obvious solution was to see that both hotels got their federal grants. That presented Wright with one immense problem. The HUD fund for such projects was, at that point, only $21 million for the entire United States. It would be difficult enough for Fort Worth to get one grant for $3 or $4 million, but half of the entire budget would be unthinkable. Except to Jim Wright. After 25 years of directing federal dollars into Fort Worth, Wright has built a reputation – and an incredible power base – as an economic messiah. He really had very little choice but to go back to the mountain for another federal miracle.

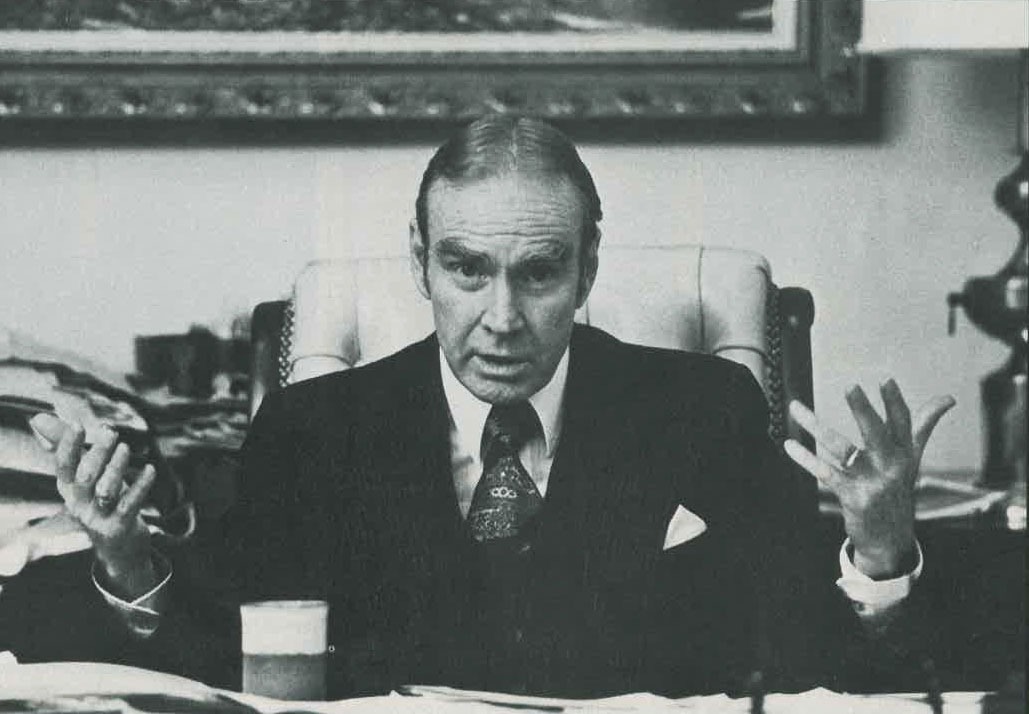

He started by summoning the appropriate HUD administrators to his office on the ground floor of the Capitol building. Wright has become notorious in Washington circles for serving people sandwiches and sales pitches during the noon hour. Wright’s fundamental weapon as a politician is that he is peerless as a salesman. In Jim Wright’s House Majority Leader’s office, the axiom that there is no free lunch holds truer than anywhere else in Washington. People come away with promises to keep.

And so it was that Wright approached the HUD hierarchy. He told them he’d heard that one of his House colleagues, Ed Boland of Massachusetts, had slashed the coming year’s HUD Urban Development Grant budget in half in subcommittee. That didn’t seem like such a good idea. And, by the way, there was this problem in Wright’s home district. A matter of some badly needed Urban Development Grant money from this year’s budget. Perhaps Wright might be able to speak to Boland for the HUD people and, well, maybe they could think of something to do for him in return.

So The Deal was made. Wright followed through with his end of the bargain, convincing Boland of the potential ill effects of cutting the HUD budget. And the HUD administrators did their part. Both Fort Worth projects would get their federal millions. Both sides would win. And most significantly, Jim Wright would win. Again.

James C. Wright wins ten times as often as he loses because he is one of Washington’s most skillful practitioners of the central rule of politics: A favor performed is a favor owed. It is Capitol Hill’s own version of the Golden Rule – do unto others so they will do unto you when you need them.

When the current Texas crop of freshmen Democratic Congressmen was campaigning for election two years ago, Wright got involved. At the very beginning of their campaigns, he gathered all the Democratic candidates at the Airport Marina Hotel at Dallas-Fort Worth Airport and conducted a seminar on how to win elections. “After the seminar was over,” recalls Dallas Representative Martin Frost, “he had a little reception for us with a group of the people who are his campaign contributors. Most of us came away with contribution pledges. I couldn’t help but be impressed. There are a lot of politicians who are willing to give you their advice on how to run a campaign, but most of them guard their money sources… they wouldn’t let you get near them.”

After the election, Wright took the new Texas freshmen under his political wing like a mother hen protecting a new batch of chicks. He counseled them about what committee assignment would be best for their careers. And he used his influence as House Majority Leader to see that every one of them got assigned to the committee of his choice. (No other state’s delegation got all its freshmen on their first-choice committees.) In a couple of cases, it took some extraordinary work by the Deal Maker. Marvin Leath, a Waco freshman, wanted to be on the Public Works Committee, where Wright has spent decades. But initially Leath didn’t get assigned to Public Works. So Wright used a little counter ploy to increase Leath’s base of support. He managed to get Howard Wolpe, a Michigan Democrat, blocked from a committee assignment he and his backers wanted. Suddenly, for some reason, the Michigan delegation got interested in getting Marvin Leath appointed to Public Works. Their support was enough to turn the tide. In an unprecedented move, the Public Works Committee was expanded by one seat so that Leath could join the committee.

But Wright pulled off an even bigger coup for Frost. There has been a longstanding, unwritten law that a freshman is never appointed to the House Rules Committee; the position is just too powerful. Because the Rules Committee is central to the process by which bills and amendments flow through the Congress, any member of the committee automatically has the ability to stop any piece of legislation in its tracks. House Speaker Tip O’Neill, who makes the Rules Committee appointments, was a firm believer in keeping freshmen out. But an unusual situation presented itself. With the 1978 congressional term, a vacancy existed on the Rules Committee that was, by tradition, a Texas seat. But the Texan in line for the seat, Jim Mattox, had just narrowly defeated Republican challenger Tom Pau-ken for re-election and was considered vulnerable, a liability. House leadership did not want Mattox on the Rules Committee. O’Neill suggested to Wright that perhaps theTexans should sit this session out, let the “Texas seat” go unfilled until the next session, when a qualified veteran would be available.

But Wright appealed to O’Neill’s sense of propriety and tradition. Texas has to have that seat, he said. And besides, there just happens to be an exceptionally well qualified freshman who can do the job. Young guy named Martin Frost. Solid as a rock. He won’t let the leadership down.

O’Neill relented, and Frost got a spot on the Rules Committee. Now Frost, who is quick to admit that he owes his political life to Jim Wright, has been thrust into the center of the House leadership clique. The appointment has enhanced Frost’s power tremendously; and, of course, it hasn’t hurt Jim Wright’s power base either.

Every now and then, it is time for Wright to call in the IOUs. Last spring, Democratic leadership was in a pitched battle with the Republicans and a group of conservative Democrats over a budget limitation amendment by Representative Marjorie Holt, Republican of Maryland. The vote was not to be the final step in the 1980 budget process, but it had developed into a power play; both sides wanted it badly. It was going to be close and everyone knew it. Wright went to the Texas Democrats and told them he needed this one. He didn’t care if they couldn’t stick with him later in the budget debate, but at this point, he had to have their votes. All 20 Democrats in the Texas delegation cast their votes with Wright. The Holt Amendment was rejected, 198 to 218. Twenty votes.

“There is no question that Wright’s ability to get all the votes in his delegation when it’s really backs-to-the-wall time gives him tremendous power with the House leadership,” one of Wright’s peers said recently. “All the other states with big Democrat delegations are too fragmented to be delivered in one big chunk. It gives Jim a tremendous bargaining tool.”

It is little wonder that with this kind of power base on Capitol Hill, Jim Wright has been able to outdo all his peers at what every Congressman has to do: send federal dollars home to his district.

A Michigan State University study, completed in November, set up a “yield ratio,” comparing the amount of federal income taxes paid in a Congressional district with the amount spent on defense contracts – the traditional political plums – in the district. The study showed that 305 congressional districts showed a net loss, 105 showed a net gain. While some of Wright’s Dallas peers like Jim Mattox and Jim Collins finished on the minus side of the ledger, Jim Wright’s district was the biggest winner in the country, with a net gain of $1.6 billion.

Shortly after the Michigan study was published, Jim Wright took to the editorial page of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to say that the report “carried all the logic of the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland.” All those fat defense contracts, Wright wrote, came to Fort Worth because the workers at Bell Helicopter and General Dynamics were so “skillful and dedicated . . . and more deeply involved than any other [work force] in the United States in providing weapons and services” for the security of the nation. Shucks, he said, he couldn’t take credit for all those defense dollars.

But members of the Wright camp on Capitol Hill are quick to point to the Michigan study as proof of his effectiveness. As long as he can do such a superlative job of directing where the tax dollar goes, Jim Wright will have tremendous power. The same rule that applies on Capitol Hill is law back home in Fort Worth: A favor performed is a favor owed. And lots of powerful people in Fort Worth owe Jim Wright lots of favors.

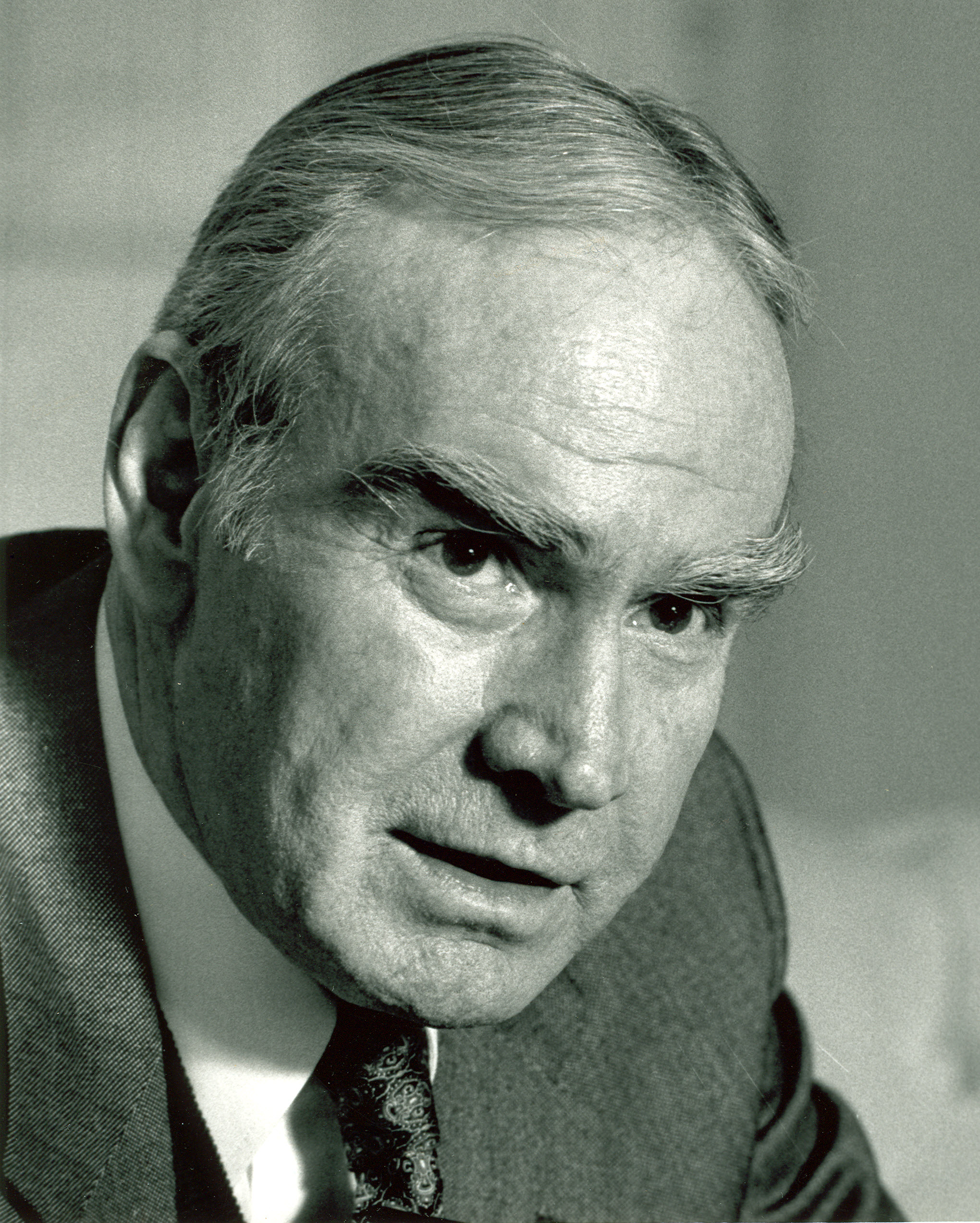

But Wright’s power on Capitol Hill is obviously not drawn exclusively from his ability to cut deals for his peers. U.S. News & World Report surveyed the House of Representatives in mid-January this year in an attempt to find out who runs Congress. When asked who the most respected House member was, the Congressmen voted Wright into first place. House Speaker O’Neill finished third. Wright also finished first in another important category: most persuasive speaker. In a profession in which every member fancies himself another Henry Clay, Wright, who has been labeled in the Washington Post as “Mr. Slick,” was voted the best orator of all.

Things haven’t always gone well for Wright. In fact, 32 years ago, at the age of 25, he had all the earmarks of a political has-been. He would later admit that many of his- colleagues in the Texas Legislature considered the idealistic young freshman from Weatherford the prime candidate for laughingstock of the session. When re-election time came around, many of his neighbors would whisper that he was a hothead, a Communist, and possibly even a murderer.

It is significant that in Wright’s early childhood, he wanted to be a professional fighter like his father. He can still remember when his dad bought him a punching bag. It would also have a great shaping effect on young Jim’s life that his father had quit the boxing ring to become a salesman. Jim Wright would ultimately become both, the salesman and the fighter. On the one side, he has always been the diplomat – controlled, calculating. Yet those who have known him for years will say that he is also a man of passion. Just beneath the smooth veneer of the salesman lurks the zealot, the idealist, the boxer ready to go 15 rounds to reach his goal. If all the sales talks fail, Jim Wright has always been ready to put on the gloves and slug it out.

By the time Wright was 14, he had mastered the politician’s art of indirection. He decided soon after enrolling in Adamson High School in Oak Cliff (his father’s job had taken the Wrights to Dallas) that he wanted to be captain of the football team. He thought the best way to accomplish that would be to make an impression on the coach, B.R. Harris, who was also the history teacher. But something happened in the history classes that Wright hadn’t planned on. He got carried away with history. The year was 1937 and the attention of the students was focused on Europe. What better way to guard the world from people like Hitler, to change the course of history, Wright thought, than to become a United States Congressman? From that point on, Wright knew that he was going to be a Congressman. He would study more history, journalism, and most of all, speech and debate. All the great politicians were masterly speakers, persuasive men whose vocabularies were arsenals. He would become one of those men.

By 1938, Wright was in politics, working as a volunteer in the gubernatorial campaign of Ernest O. Thompson. Thompson got trounced in the Democratic primary that year, but the defeat did nothing to dampen the political appetite of young Wright. Wright figured he could do a damn sight better than Thompson had done, and besides, he wasn’t that interested in becoming governor. He was going to be a Congressman.

He continued preparing himself, first at Weatherford College, in the small town west of Fort Worth that was his boyhood home, and then at the University of Texas, where he continued studying journalism, political science, and public speaking.

Like most of the young men of his generation, Wright spent the war years in uniform. But he let his military experience push him further toward his political pursuit. When he got out of the Army and returned to Weatherford, he used his association with the Veterans of Foreign Wars as a political vehicle. There were lots of hands to shake at the VFW hall, and lots of audiences that just loved to hear a good speech on Americanism. But Wright was also a central figure in the Young Democrats in Weatherford, Fort Worth, and Dallas. The Young Democrats was one of only a handful of organizations in active and vocal opposition to Joe McCarthy, trying — usually in vain — to tell the country that not all intellectuals were necessarily loyal to Joe Stalin.

Through his association with the Young Democrats, he met many of his first political allies. Jack Carter, a lawyer and county Democratic chairman in Fort Worth in 1945, helped Wright organize Young Democrats in Fort Worth. Carter’s wife, Margaret, was to become a perennial campaign power, whose political acumen and influence in Fort Worth would last for decades.If he could not join Carter, he would simply have to beat him.

Wright had enough success with the Young Democrats to be named chairman of the Resolutions Committee of the 1945 state convention. His committee adopted what was considered at the time a radical platform: An increase in the minimum wage. A full employment act to guarantee jobs for all. Abolition of the poll tax. Federal aid to education. A world police force to stop international aggression. Lowering the voting age to 18. Wright, as the spokesman for these left-wing ideals, was already starting to ruffle some feathers. But he was winning countless friends and allies among the young idealists of the state. In the 1946 state legislative race, he would be drafted as a stump speaker by his former Dallas high school buddy Joe Bailey lrwin, as well as a handful of other reformist candidates like Ben Atwell and Mike McKool.

This campaigning would later create problems for Wright. He was crossing county lines – never an astute move – to participate in a political fight that many would consider none of his business. What was worse, in campaigning for lrwin he was working against Dallas legislator W.O. Reed, everyone’s choice to be the next Texas House Speaker. Not too shrewd. But no one was accusing Wright of being politically shrewd in those days. He was just a 22-year-old firebrand who was a darn good stump speaker.

Several significant events in Wright’s political career occurred in 1946. Wright still remembers hearing one of Congressman Fritz Lanham’s speeches before Lanham retired that year after 28 years in Congress. He held the spot that Wright would later hold for a quarter of a century. When Lanham spoke one morning to the First Methodist Church of Fort Worth, young Wright made a point of being in the congregation.

“I was entranced,” Wright would later write in his memoirs. “The old thespian had mastered every trick in the elocutionist’s arsenal … Not until the finish (of the sermon) did I realize the total thrall of hush and motionlessness into which the huge audience had been transfixed. I went home that afternoon and wrote two sermons.” There, Wright thought, was a real Congressman at work.

Lanham had announced that he would not run for re-election, but Wright was too young to run for the empty Congressional seat. “I felt somehow cheated that he hadn’t waited just two more years until I could have qualified by age to replace him,” Wright would later write. He would have to settle for the only substitute available for a man his age, a seat in the Texas Legislature.

Another Sunday gathering would bring about another significant event, his first meeting with Amon Carter Sr. Carter was on the speaker’s platform at a ceremony in Weatherford to welcome back a hometown war hero, General Hood Simpson. Wright, who was in the audience when Simpson spoke, decided to seize the opportunity to try to meet Carter. He knew that Carter, publisher of the Star-Telegram, owner of the only television station in Fort Worth (and half of everything else worth owning in Tarrant County), was the reigning kingmaker of the era. Any political campaign in Tarrant County started with the candidate kissing Carter’s ring. He had a well-earned reputation for propelling to stardom the people he liked, and crushing those he didn’t. When the ceremony was over, Wright rushed forward to the speaker’s platform and made his way through the crowd surrounding Carter.

He thrust out his hand to Carter and gave him his biggest smile.

“Hi, I’m Jim Wright, Mr. Carter.”

Carter gave him all the attention you’d give a hot dog vendor at a baseball game.

“How do you do,” Carter said, with a tone that left Wright feeling he was annoying the kingmaker.

“You don’t know it, but I used to work for you,” Wright said. He was fully prepared to give Carter a discourse on how he had been a stringer for the Star-Telegram. He was going to try to shift the conversation from that to politics, asking Carter who he thought would be the replacement for Lan-ham. But he never got the chance.

Carter answered Wright’s statement with a “That’s nice” and then abruptly turned away. Wright was both embarrassed and outraged. He knew right then that there would be an immense obstacle in his pathway to Washington: Amon Carter. Wright had too much pride to consider going back again and courting Carter’s favor. If he could not join Carter, he would simply have to beat him.

Most of Wright’s interactions with the citizens of Fort Worth and the surrounding communities would not be nearly so frustrating, however. When Jim Wright wasn’t busy selling himself and his political allies to the people of the area, he was busy selling something that would earn him cash. Shortly after returning from the service, he took a job as a membership salesman for the National Federation of Small Businesses, a trade organization that was a low-budget version of the U.S Chamber of Commerce. The first month Wright cleared $600, twice as much as the local county judge was making at the time. As important as the income was the fact that it gave Wright a chance to hone his rhetorical skills, and do so with a group of people that would someday be his constituents.

But it wasn’t his verbal skills that ultimately made him a hit with his fellow veterans at the Weatherford American Legion hall. It was Jim Wright the fighter.

One night at a legion meeting, Wright, who must have looked like the picture of intellectual snobbery in his suit and tie, collided with a big, belligerant Legionnaire named Dub Tucker.

The confrontation had all the sophistication of a melee between two small boys in a school yard. Tucker bumped into Wright and then, scowling at the young salesman, declared in a rather loud voice that Wright was “a chickenshit sonofabitch.”

“Don’t know why you call me that,” Wright smiled. “I haven’t done anything to you.”

“You’re a damn sissy,” Tucker said.

“Look Tucker,” said Wright. “I don’t know you and you don’t know me. So let’s just…”

“I know you alright,” Tucker snapped. “You’re a commie sonofabitch.”

That’s when the fighter took control. There was nothing the salesman could do to stop him.

“I’m not going to let you call me that,” Wright heard himself tell the big man.

At that point Tucker took a swing at Wright. Wright pivoted, rolling away from the punch, and then buried his left fist into the man’s stomach with all his strength. It was followed rapidly by his right. Tucker backed away but Wright followed him, delivering six more rapid blows before the man collapsed.

Wright was an instant hero with the Legionnaires and all the other veterans’ groups in the area. He might have some left-wing ideas about McCarthyism and issues like “academic freedom,” but he sure could handle his fists like a real American. Wright would later decide that it was probably the fight in the Legion Hall that swept him into the Texas Legislature as a representative of Parker County in 1946. At 22, he became the youngest member of the legislature.

There is probably no more appropriate political baptism for a young, naive ideologue than a stint in the Texas Legislature. It is a boot camp for the conscience, a training course that will quickly wear away any wide-eyed notions that laws are based on what’s good and fair and right for the people of Texas. This was especially true in 1947, when Wright packed off to Austin with a whole laundry list of reformist measures that he was sure he could turn into laws.

Needless to say, Wright had minimal impact on the 1947 session of the legislature. A lobby control bill that Wright introduced was referred to the House State Affairs Committee for consideration. From there it went to a subcommittee for further consideration. Years later, Wright would write in his memoirs, “So far as I know they’re still studying it, ver-r-ry carefully.”

In the entire session, Wright got one bill passed. It provided a small amount of state money to local water and soil conservation districts – hardly a bill to raise controversy in a rural-dominated legislative body.

It was some of the bills that Wright didn’t pass that would begin to build his legislative reputation, and earn him some formidable enemies. He was co-sponsor of a bill that would have placed a direct tax on the production of oil, gas, and sulfur. It would be difficult to find a more powerful lobby in this state than the representatives of Texas mineral producers. The bill never made it out of committee. But doubtless such legislative attempts convinced some of the more conservative political minds in Texas that this young Wright could be dangerous.

But the session was beneficial to Wright in several ways. He was making friends among his colleagues. About a dozen of them asked him to come home with them to their districts to speak at civic clubs and other gatherings.

“I was learning that one’s success in the legislature depended less actually upon his ideology than upon his acceptance as a person,” Wright later wrote.

So, on balance, Wright left Austin at the end of the 1947 legislative session with no reason to think he was going anywhere but up.

He didn’t feel too alarmed the following year when Eugene Miller filed against him for re-election. The local soil conservation district was able to buy earth-moving equipment with a state grant that was a result of Wright’s legislative bill. The local dairy farmers, a force in the rural community, were solidly in his camp. The business that Wright operated with his father, a promotion organization called the National Trades Day Association, was beginning to flourish.

Sure, he’d seen Miller verbally tear apart Weatherford lawyer Ben Hagman (father of actor Larry Hagman) in a three-candidate state senate race two years before, setting Hagman up for defeat by State Representative Bob Proffer of Denton County. Miller had been formidable in a whispering campaign that ensued after Hagman and Proffer went into a runoff. But what were they going to whisper about Jim Wright? He had a wife and young son, a family-owned business. He was the picture of stability, even at age 25. And he was still the darling of the after-dinner speakers circuit. Weatherford College had even chosen him as its outstanding alumnus that year. Wright felt invincible.

But then a weird sequence of events unfolded.

Wright was sitting at the counter of the Nook Cafe one noon when a schoolteacher named Floyd Bradshaw struck up a conversation.

“I like the things you’ve done in the legislature,” he said. “But I’ve been disturbed by the talk that you’re a communist. What do you say to that?”

Wright was quick on the defense, branding any talk that he was a communist as “a lie and the talk of ignorant people.” The two men went into a long conversation about the evils of communism, and when Bradshaw left the cafe, Wright thought he’had a convert.

Just before the filing deadline, Floyd Bradshaw announced that he was a candidate for Wright’s seat.

The young legislator considered himself trapped in the same vise that had squeezed Hagman. Miller, an accomplished stump speaker and an expert at excoriating political opponents, could go on the attack, calling Wright everything but Joe Stalin’s brother-in-law. And Bradshaw, a mild-mannered educator in his late thirties, could sit back and play Mr. Clean. Wright knew he was in for a tough fight.

Wright’s fears were proved valid. The first time he shared the platform with Wright, Miller told the audience that the young representative had voted last term for a bill that “would let every uppity nigra with a high school diploma infiltrate the University of Texas Law School.” (There had been no bill dealing with the integration of the University of Texas Law School, but Wright had voted to create a black law school in Houston.) Each time the three candidates spoke, Miller leveled some new charge at Wright, while Bradshaw acted the perfect gentleman. Wright was determined to keep his cool. This wasn’t a job for the fighter; it was a job for the diplomat, the salesman. Wright never directly responded to the allegations, but instead told the audience that he thought they deserved to hear about the issues rather than be exposed to meaningless mudslinging.

Then it happened. Eugene Miller was brought to a Weatherford hospital about 8 o’clock one night. He’d been shot. He was bleeding badly. Wright, who had signed up as a regular blood donor, was called to the hospital in case a transfusion was needed.

Miller told the staff at the hospital that he had been staying at a farmhouse near the rural community of Garner when a young, slender man drove up to the house, called him out into the darkness in the front yard, and shot him. The man jumped in his car and disappeared down the dusty road.

It wasn’t long until the whispering started. How did Wright get to the hospital to give blood just minutes after Miller was brought in? Then came the tales of how the volatile Wright had used Dub Tucker for a punching bag at the legion hall a couple of years before.

Then J.A. Coalson, a farmer who lived near Weatherford, began telling people he’d seen Wright out on a country road one day, practicing with a pistol, shooting at a telephone pole. He knew he’d heard the crack of pistol shots. When Wright heard the story, he went to Coalson’s house.

“Those weren’t pistol shots,” he said. “That was a tack hammer. The sound you heard was the vibration of the wires when I hit the telephone pole with the hammer.”

Coalson allowed that he had seen campaign posters, but wasn’t convinced.

“I ought to know the sound of a pistol when I hear it,” the old man said.

Wright knew he was in big trouble. The election was drawing near. There was no time to talk to all his neighbors, to try to convince those who thought maybe he had gotten so worked up over the political campaign that he killed a man.

The authorities investigating the murder said Wright was not a suspect. But there was no other suspect in the killing, either. (The case, in fact, is still unsolved.) Wright decided to ignore the rumors. No sense giving credence to them. Besides, Wright feared that if he entered a debate it might end with him punching someone in the face.

Two days before the election, Floyd Bradshaw ran an ad on the front page of the Weatherford Daily Herald, stating simply that he was opposed to “communism.” Wright was furious at the implication that the incumbent legislator was for communism. Wright tried to counter the implied charge with a last-minute speaking campaign. If he could just get enough people together, he figured, he could win them over. It had always worked before.

But fate was working against him. A final-night rally on the town square, always heavily attended in Weatherford elections, was moved to the college campus because of road repairs. Most townspeople didn’t hear about the move, and the turnout was only a handful of people instead of the usual couple of thousand. Wright poured out an emotional speech to those who were there to listen. He left the rally feeling that he had wowed the audience.

The next night when the ballots were counted, Wright had carried the “city” boxes in Weatherford, but had lost heavily in the rural areas around the community of Garner, where Miller had lived, and Adel, J.A. Coalson’s home. When all the votes were counted, Floyd Bradshaw had handed Wright the only election defeat he has ever suffered. By a margin of 39 votes.

Wright’s wife, Mab, wanted to pack up and leave, take their child and all their belongings and move to where nobody had ever heard of Eugene Miller or Floyd Bradshaw. But Wright resolved to stay in Weatherford. He wanted to prove that all those who had whispered about him were wrong.

And that’s exactly what he did. Operating the family business, continuing to speak at Rotary Clubs and high school commencements, he went about showing all who had doubted him that he was a solid member of the community. Soon the controversy had faded. By the time he was 26, Wright had become the mayor of Weatherford. The boy mayor’s position had an aura about it that served him well. By 1952, at age 29, he was elected president of the League of Texas Municipalities, a prestigious 40-year-old organization that had clout in the legislature as well as in cities and towns across the state. Wright was back on track. Washington didn’t seem any more remote to him than it had when he was 14.

And so it was no surprise that when the 1954 Congressional race rolled around, Wright challenged Wingate Lucas, the man who had replaced Fritz Lanham when he had retired in 1946. Beating a three-term incumbent would have been difficult enough, but this race had an extra factor. Wingate Lucas was Amon Carter’s Congressman. To beat Lucas, Wright would have to beat Carter, and do so not just on Wright’s home turf in Weatherford, but in Fort Worth, the city that Amon Carter owned. The candidates would talk about leadership and service to the community and taxes; but the real issue would be whether Amon Carter could be challenged. In the minds of many, if Carter had chosen Lucas to be the area’s representative in Congress, then Lucas probably deserved to be a Congressman.

But one factor that Wright had going for him was that Fort Worth was changing with the times. There were plenty of people in town who no longer felt that the city’s leadership structure should be a patriarchy. Wright played to that group.

Of course, when the candidates debated, they talked about issues like Congressional seniority and experience, and what each could do for Fort Worth in the halls of the Capitol.As election day got closer, the campaign got bloodier.

Wright told an audience in Arlington Heights one evening that Congress should not be a “lifetime job” and that seniority wasn’t nearly as important in Washington as one’s abilities and determination. He would later find out just how fallacious that argument was. But at the time he had to hope the voters would buy it.

As election day got closer, the campaign got bloodier. Wright called Lucas the tool of a political machine that used economic pressure to force its will on the community. He did everything but name Amon Carter personally. At the time he made the charges, he was speaking on WBAP-TV and radio, both of which belonged to Carter.

Lucas replied that Wright was part of a left-wing conspiracy and was the candidate of “radicals.” He said that the big-time labor leaders were out to get him and that Wright was their hit man.

The Star-Telegram, meanwhile, did its part to support Carter’s Congressman, saying on its editorial page that Wright had no “well defined ideas” for how to achieve his Congressional goals and that Lucas, of course, should be sent back for another term with a strong electoral mandate.

Then the bomb hit. About two weeks before election day, the Post Office Department filed mail fraud charges against Wright, his father, and the National Trades Day Association, the company they owned. The Wrights were charged with “conducting a scheme for obtaining money through the mails.” A hearing was set for July 22, three days before the primary election. Wright’s attorney tried to get the hearing date moved up, but it was instead delayed until after election day.

Wright was quick to contend that the charges were “politically motivated,” saying that his company had been conducting business for 20 years in a manner identical to that which brought the charges against him days before the election. He said the charges were doubtless the work of Lucas supporters, pointing out that Washington reporters were “tipped off” to the story by a member of Lucas’ office staff.

He would have to hope that people believed that, since there would be no way to clear himself of the charges before the election. He would have to hope that the salesman had done his job, peddling enough Jim Wright charisma to turn the tide.

But the day before the election, the fighter had his way. He decided to take off the gloves and get in the ring with his opponent. Not with Wingate Lucas, but Amon Carter. It would be in Carter’s own arena – the Star-Telegram.

Wright plunked down $974.40 (a huge sum in 1954) for a three-quarter page ad in the Star-Telegram, an “open letter” to Amon G. Carter. It was tough.

It said that the newspaper had engaged in “misrepresentation” about Wright’s campaign; that the news columns had largely ignored Wright’s campaign while the editorial pages had deceived people about his qualifications.

But most of all, the ad did something no one had had the audacity to do before: It challenged Amon Carter personally. “You have finally met a man, Mr. Carter, who is not afraid of you … who will not bow his knee to you and come running like a simpering pup at your beck and call.

“It is unhealthy for anyone to become too powerful, too influential, too dominating. It is not good for democracy. The people are tired of one-man rule.” The ad went on to call Lucas Carter’s “errand boy.”

When the votes were counted, Wright had won by a 3-to-2 margin. He carried every county in the district, beating Lucas 34,263 to 25,180 in Tarrant County. The fighter had beaten the kingmaker.

Amon Carter and Jim Wright would never become close friends. But in any power struggle, the loser eventually accepts the winner. Wright, realizing that one election was certainly not going to make the richest and most powerful man in Fort Worth quake in his boots, wrote Carter another letter (this one not for publication in the newspaper) suggesting that the two should work together for the good of the city. Carter died long before Wright’s Congressional career began to blossom, but Amon Carter Jr., publisher of the Star-Telegram, would come forward to embrace the representative. He in fact became president of the Jim Wright Congressional Club, an organization whose sole purpose was to raise funds for Wright. And the Star-Telegram editorial page, traditionally supportive of incumbent politicians anyway, would come to read like a Jim Wright fan club newsletter.“It is unhealthy for anyone to become too powerful, too influential, too dominating. It is not good for democracy. The people are tired of one-man rule.”

Wright has never faced a really tough election since 1954. The postal fraud charges against him were eventually dropped and he never had to face scandal as a campaign issue in subsequent elections. In 1963, the media took him to task over the activities of the WSB Corporation, a building company formed by Wright’s wife, Mab, Weather-ford lawyer Borden Seaberry, and builder Wayne E. Bass. When the company got a contract for an FHA-financed building project, the allegations began to fly. Wright replied that his wife had dropped out of the company before it got the housing project contract. The company ultimately dissolved after the bad publicity, but Wright’s career didn’t. In the 1964 primary, the first election contest after the WSB controversy, Wright beat former three-term Fort Worth City Councilman Tommy Thompson by a 10-to-l margin, carrying every vote in some precincts. By then, of course, Jim Wright had become a Fort Worth institution. Star-Telegram writer Roger Summers still remembers covering the ballot canvassing at the Tarrant County Court House, and seeing one elderly woman cry when she learned that in one precinct, eight voters out of a thousand had the audacity to vote against Jim Wright. The Star-Telegram said in a front-page story that Thompson had “apparently stepped out of his league” when he decided to run against the incumbent Congressman. Wright didn’t face another election challenger until 10 years later, when he demolished Republican grain dealer James Garvey, who carried only 20 percent of the vote.

Wright’s early election victories have to be attributed to his ability to sell and resell himself to his constituents, because he certainly wasn’t bowling over his peers in Congress.

When he got to Washington in 1954, he found that the rule that freshmen representatives should be seen and not heard was even truer than it had been in Austin. Fledgling lawmakers weren’t given leadership roles. Like other young Southern Democrats, he had the fatherly advice and help of Texas Representative Sam Rayburn, the House Speaker, but Wright certainly had nothing that would even begin to resemble clout.

He became aware of how tough it was going to be to climb the leadership ladder in 1957, when he introduced a bill to expand the science curriculum in the nation’s schools. The country had post-Sputnik jitters, and the bill was perfect for the times. Wright was allowed to testify before a subcommittee of the House Committee on Education. But when the bill, which was later passed and became the National Defense Education Act of 1957, came out of committee, it bore the name of Rep. Carl Elliot, the chairman of the subcommittee to which Wright had presented it.

By the early Sixties, Wright’s Congressional impotence was beginning to get to him. One afternoon at a gathering at Vice President Lyndon Johnson’s Washington home, he made a sales pitch to try to advance his career in some other direction.

“Lyndon, I’m frustrated,” he told Johnson. “I’m not getting anywhere here. I’m spinning my wheels. I am not achieving any great things. Haven’t you got some kind of a job for me? Make me an ambassador. . . maybe something in the administration where I could really feel like I was doing something.”

Johnson gave Wright a quick lecture on the allocation of power in Washington. Everybody is frustrated, he said. An ambassador or a cabinet member can be fired in the course of an afternoon. Even the president is only as effective as the programs he can get through Congress. There is no job, Johnson told Wright, that is essentially better than being a member of the House or Senate. In short: Go back and pay your dues, boy, make the most of what you’ve got.

“It was an eye opener to me,” Wright recalls. “I began to realize that in a government as big and diverse as this one, that power is dispersed so widely that no single individual can have his way all the time …. For the most part it is a team effort and it involves an enormous amount of compromise.”

He took a shot at the Senate in 1961, but Finished third in the Democratic primary. When the next Senate race came around, Wright decided not to run after testing the political waters. The best route to power was obviously going to be the legislative body that he’d fancied ever since he was 14, the U.S. House of Representatives.

Unquestionably the biggest single element in Jim Wright’s rise to the ranks of theTitans of the Potomac was his ability as a salesman. He sold himself to his peers with methods like memorizing the House photo directory each year so he could greet each member by name in the hallways. He sold his colleagues to their constituents, traveling thousands of miles to speak in their home districts and enhance their re-election chances. He sold his district’s wares to the Congress and the White House, hawking first B-58’s and then F-lll’s for General Dynamics, helicopters for Bell Helicopter-Textron, and even the A-7 for LTV. (Congressional insiders will tell you that Wright and Rep. Martin Frost, whose district is home for LTV, know that the critics who say the A-7 is obsolete are probably right.)

The thousands of people in Wright’s district who draw paychecks from General Dynamics or Bell Helicopter or any of the subcontractors who do business with those firms know that Jim Wright, as much as any other single individual, is responsible for their good fortune. That’s partly because Wright and his supporters never let them forget it. No one ever accused Wright of being reticent in taking credit for his accomplishments.

A telling statement about Wright’s philosophy of selling oneself to one’s constituents was made two years ago when the Washington Post published portions of a “How to Get Re-Elected” memo that Wright had sent to his Democrat peers.

“From your case files,” the instructions read, “find someone who the congressman has really been able to help. Try to choose a case that has at least some element of drama or human interest. Did you help get a soldier home on emergency leave from Afghanistan just in time for his mother’s surgery? Is there a family you helped reunite through an immigration case?…

“After choosing a subject, get him on the telephone. Tell him several people have agreed to tape brief radio statements telling how the congressman helped them and you wonder if he would like to make one.

“Putting yourself in the role of the subject, sit down and write a script for him. Whenever possible, use his own words and phrases. . . [If the person has difficulty reading the script for broadcast] sit down at the recorder with your subject and . . . read it to him one line at a time and get him to repeat your exact words. Then, back at the studio, get a technician to edit out your voice and string his sentences together. That way he won’t sound as if he is reading.

“Get about 20 of these little testimonials, schedule them for broadcast immediately prior to election day, and it will sound as if the congressman has personally helped everybody in town.”

Wright, who obviously didn’t care for the Post publication of his campaign pointers, told the newspaper he did not think the methods “exploitative” because it only used “volunteers.”

The Post article was almost a blueprint for a film called “Thank You Jim Wright,” which was shown at Wright’s 25th anniversary appreciation dinner at the Tarrant County Convention Center last year. An audience filled with political luminaries like House Speaker O’Neill and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance watched a thirty-minute testimonial giving Wright credit for everything but single-handedly winning World Warll.

Mayor Woodie Woods, standing in the middle of Main Street in a cowboy hat, tells the camera: “There’s no doubt about it. Without Jim Wright, Fort Worth would not have gotten the federal grants that are making it possible to build a new hotel at First and Main and a new Hyatt Regency here. . .” Woods seems to be reading. They should have worked with him more.

Everyone who’s anyone in Fort Worth is in the film. American Airlines President Al Casey talks about how Wright kept the airline’s relocation deal from falling through. Amon Carter Jr. talks about how much the city owes Jim Wright. Incredible overkill, but then Wright never was shy about selling Wright.

Jim Wright’s sales pitches over the years have frequently been less than subtle, but they have worked. They have given him re-election by overwhelming margins, and that counts for a lot on Capitol Hill, where seniority and a hammerlock on one’s congressional seat are the foundations of a power base. It was doubtless Wright’s seniority that put him in a position to make his move when House Speaker Carl Albert retired in 1976, causing a changing of the guard that would leave the House Majority Leader’s job open. The fight to fill that opening would determine the structure of House leadership for decades to come.

In some ways, Wright’s race for House Majority Leader was similar to his first race for Congress. Wright was running for Majority Leader against a man who already had a lock on the job. Rep. Phil Burton had made it clear to all that he wanted the majority leader’s job two years before Speaker Carl Albert announced his decision to retire.

Burton had gained from his alliance with Rep. Wayne Hayes of Ohio, who was handling national Democratic Party money before the 1976 election. Wright contends that Hayes would tip Burton when the party was about to send a thousand dollars or so to a Democratic congressional candidate so Burton could call first. “Need some campaign money?” Burton would ask. When the candidates answered “Yes,” and they always did, Burton would tell them he was going to talk to Hayes and put in a good word for them. Burton did a good job of organizing the support of the freshman Democrats who were elected in 1976, and had a lot of momentum going into the House leadership election. But his election was not in the bag. For one thing, O’Neill, whose promotion from Majority Leader to Speaker was a sure thing, couldn’t stand Burton. And, as one Capitol Hill insider put it “there were just too many people in the House who thought Burton was too Machiavellian.”

Several other candidates had announced their intentions to seek the majority leadership. John McFall, the majority whip, who would normally be in the line of succession for the post but who had been hurt when he had received $4000 from Korean businessman Tong Sun Park, was running. So was Representative Dick Bolling of Missouri, who had run for the post before and was generally considered too old this time around.

In the summer of 1976, Wright and some of his staff drove to West Virginia to campaign for Wright’s old friend Representative Harley Staggers. Staggers asked Wright if he’d thought about trying for Majority Leader and Wright said he had been thinking about it but hadn’t decided. The more they talked about it, the better it sounded. All the other candidates had weaknesses, and Wright might just have a chance of forming a coalition that would get him elected.

Starting with all but two of the Texas delegation – Bob Eckhardt and Jack Brooks had already pledged to Burton – Wright started putting together a list of votes he could count on.

A small task force of Wright supporters was formed: Rep. Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois; Rep. Bill Alexander of Arkansas; Wright’s chief political staffer, Craig Raupe (who had first gone to work for Wright when he was mayor of Weatherford). During the summer, they counted the yes, no, and maybe commitments every day; they held meetings at least once a week.

Meanwhile, Jim Wright crisscrossed the country, campaigning for Democratic Congressional candidates. There were more than 50. The name of the game was to determine which ones would win and get involved enough in their campaigns to make them feel a debt of gratitude. This wasn’t easy, considering that the other candidates for Majority Leader were busy doing the same thing.

By the time the general election was over and the December leadership caucus rolled around, Wright figured he had 88 votes in his pocket. “If McFall doesn’t make it,” he would ask a colleague, “will you give me your vote on the next round?” By election day, the campaigning was hot and heavy. “Can I be your second choice?” a candidate would ask one of his peers. “Okay, can I be your third choice?”

Wright’s strength was that he was the candidate who was the least offensive to a large number of Democrats. Boiling had entered the race largely as a “stop Burton” candidate, but he was too old for a lot of representatives, especially the young members who had knocked many of their older colleagues out of committee chairmanships. McFall had the Koreagate liability, and consequently was at the bottom of a lot of Congressmen’s lists. And now Burton, in addition to being anathema to O’Neill and his close followers, was starting to feel some guilt-by-association heat from the fact that his old friend Hayes had cratered out politically after it was revealed that the taxpayers had been paying his secretary to go to bed with him. Everybody in the race had at least one dent in his armor. Even Wright.

“A lot of the younger members thought Jim had a bit too much of the snake oil salesman in him,” says Seth Kantor, Washington correspondent for the Atlanta Constitution. “It didn’t really help his image much that he wore white shoes on the House floor in the summertime.” But of the political liabilities, Wright’s would turn out to be the most tolerable to the largest number of representatives.

When the first caucus ballot was taken, Burton came storming out of the starting gate with 106 votes, about 30 short of a clear majority. Boiling had 81, Wright 77, Mc-Fall 31. The procedure was for the last man to be dropped from the race on each round. Since McFall and Burton are both from California, it appeared that Burton might be able to pick up a lot of McFall’s votes on the strength of regionalism. There was a 15-minute period between ballots for the candidates to campaign furiously. Wright did a good job.

Second round: Burton 107, Wright 95, Boiling 93. Wright had picked up the vast majority of McFall’s votes. The strategists were biting their fingernails off. Had Burton thrown some of his second-round votes to Wright in order to knock Boiling out of the running? (Burton would later deny it.) Or did Wright now have the upper hand? After all, Boiling was running as a stop-Burton candidate. If he could throw enough of his support to Wright, he would be able to achieve that goal.

Within minutes everyone knew the answer to that question. On the final vote, Wright had 148 votes, Burton had 147. One vote. It was plenty.

Wright had won a position that automatically bestows a mantle of incredible power. Among the majority leader’s privileges:

-The scheduling of each bill that comes through the House. The timing of the vote on a piece of legislation can be vital to its success.

-The right to be recognized by theSpeaker, out of turn, at any time.

-The right to be the final speaker in any debate on any issue. The last word can beimportant in the House of Representatives.In the Texas Legislature, the issues are sopredetermined that it matters very littlewhat is said on the House floor. But in theU.S. House, where many issues are regionalin nature, large numbers of members go onto the chamber floor uncommitted. To a persuasive speaker like Wright, the closing of a debate is the time to sew up the vote on an issue.

– Close contact with the White House. Wright has enjoyed a weekly audience at the White House since taking the majority leader’s position.

-Not least, the Majority Leader is the second-highest ranking member of the House. He can influence key office appointments, stall bills in the Rules Committee or zip them through, and perform a number of other procedural tasks that make him a key figure in the life or death of any legislation. It is not impossible to get something accomplished in the House if Jim Wright doesn’t like you, but it certainly isn’t easy.

During his first two years as Majority Leader, Wright used his powers judiciously, eating away at those 143 votes that had gone to Burton in 1976. And he has had great success building his influence with the basic political staple: money.

Following the tradition of O’Neill, Wright established the Jim Wright Majority Congress Committee, an organization designed to raise and distribute money for Democratic Congressional candidates. Now he gets to be the man who hands out all those thousands and reaps the attendant personal political benefits. He has done well.

Between the time the Jim Wright Majority Committee was formed in 1977 and the time Wright filed his spring Federal Election Commission report in 1978, the committee had raised more than $300,000.

The list of contributors reads like a Who’s Who of national political action committees and also includes some familiar Texas names. Western Company Chairman H.E. “Eddie” Chiles – who has sponsored a massive media campaign to tell the world he is mad at politicians and recently has run full-page ads in the Star-Telegram advocating Wright’s defeat – gave the Wright committee $5000 during the reporting period. Western Company Vice President Charles Simmons coughed up $1000; Charles Tandy, $4000; Fort Worth oilman Perry Bass, $5000; the LTV Active Citizenship Campaign, $3500; General Dynamics Voluntary Contribution Plan, $1000; $1000 each from three LTV executives and another $1000 each from three General Dynamics executives. And then there are the garment workers and the postal workers and the air traffic controllers and the railway clerks and the airline pilots, all coming across with one or two thousand per group. The list goes on and on. Most of the candidates who were given contributions from the Wright Committee in the 1978 report were young politicians in marginal races. Most were given $500 in the first round of largess. An exception to that rule was Rep. Harley Staggers, who got $1000.

In his first term as majority leader Wright did such a good job of handling the powers of the incumbency and the powers of the purse strings that support for a Burton challenge disintegrated. Burton formally announced he would not challenge Wright and Wright was re-elected by acclamation.

But the position that brought him power also brought under the scrutiny of the national press – something Wright has never really cared for.

When he announced in 1977 that his personal and political debts had become “hopelessly intermingled” and that he was using $98,701 in leftover campaign funds to pay personal-political debts and to pay the income taxes necessary when contributions are used for private use, the editorial page of the Washington Post responded with indignation. A group of Post reporters came to his office and asked him to sign documents that would allow them to go to Fort Worth to go through the records of his personal checking account back into the 1950’s. A shouting match ensued. Hell no, he told them, he was not going to have it.

Then the Post reported that he had his kin on his staff. His wife Betty, whom he married after divorcing his first wife several years ago, worked on the staff of the House Public Works Committee, on which he spent 22 years. His son-in-law’s brother was on Wright’s own staff. His daughter worked for the House Banking Committee.

Big deal, Wright responded. All of those posts were being held for legitimate reasons. The experience turned Wright into an outspoken critic of the media.

And in addition to the media scrutiny, the national office that Wright holds has made him a prime re-election target of the Republican Party, which has put him on a collision course with the second-best salesman in Fort Worth, former Mayor Pro Tem Jim Bradshaw.

Jim Bradshaw first established a foothold in Fort Worth politics five years ago with a high-voltage media campaign that enabled him to beat a car dealer for a spot on the City Council. Bradshaw’s campaign promise: He was “dynamic.” As the campaign drew to a close, Bradshaw took to the radio to blast “the establishment” and say that power had to be wrestled away from a tiny group of men that had imposed a monolithic rule on government in Fort Worth. It worked like a charm. He was swept into office by many of the same voters who had turned out to help Jim Wright fight the establishment dragons 25 years earlier. There was no Amon Carter Sr. to kick around, but the script was basically the same.

A couple of years later, long after it had been determined that Bradshaw had a deed for his city council seat, he began to think of bigger challenges.

“I’ve been thinking of making a crack at Congress at some point,” Bradshaw told me one afternoon as we sat in the Press Club of Fort Worth, talking politics and sipping Coors. “But the only thing I haven’t figured out yet is whether to be a Democrat or a Republican.” He was a purist, devoid of any “message” to send to Capitol Hill or any desire to change the world. A truly honest politician who admits to himself that getting elected is an end in itself, he was running on straight ego.

Things have changed considerably since then, however. The Republican war chest to defeat Wright has grown fatter than ever before. Oilman Eddie Chiles, the richest conservative idealist in Fort Worth, has decided that Wright is one of those evil, wasteful politicians that we’ve all heard so much about in Chiles’ radio ads. And Jim Bradshaw has got religion. He is a devout Republican now, and is entitled to all the privileges and campaign contributions that accrue thereto. Based on all that old-time political fervor, he has offered himself as a candidate against Wright.

He will doubtless do much better than all the grain dealers and other amateurs who have faced Wright before, because he knows that the campaign has to be approached in a professional manner. It is a job of selling.

Soon the campaign will start in full swing and Bradshaw will be telling audiences that Congress is not a place where a man should spend a lifetime and that seniority is not nearly so important as having a man who votes for what the people of Fort Worth really want. He will say Wright has a left-wing voting record.

He probably won’t unseat Jim Wright, but political observers are already calling the race “the toughest re-election battle Wright has ever faced.”

Even Eddie Chiles admits that it would be an uphill fight to unseat Wright and that the odds are against his man Bradshaw. But others are more optimistic.

“Jim Wright is pure poiitician,” says one of Bradshaw’s backers. “So’s our man. They are both racehorses. And if you want to beat a racehorse, you’ve got to get yourself a racehorse.”