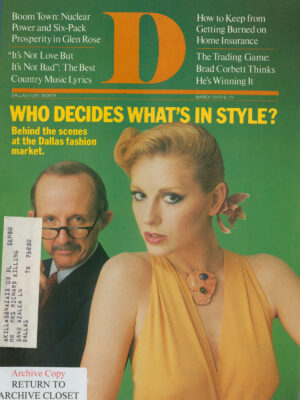

For 330 days a year the Dallas Apparel Mart resembles a gigantic self-storage warehouse – nearly 2000 locked showrooms, many emptied of everything except garment racks and a few tables, strung along 20 miles of darkened corridors; cavernous halls that echo with the faintest sound. But during the five major women’s markets (in January, March, May, August, and October) the building becomes more like Texas Stadium, with a total of over 75,000 buyers, salesmen, and models clicking through the turnstiles in search of chic and the latest news about Cheryl Tiegs. The Apparel Mart is the fashion supermarket of the Southwest, serving a twelve-state area and grossing an estimated $600,000,000 in wholesale apparel sales a year. Seventy-five percent of this comes from the small Mom and Pop stores that can’t afford to send buyers to New York or Paris, and probably wouldn’t want to anyway. Dallas is where Middle America dresses itself.

Instead of chic, I’m searching for Larry, head buyer for a group of department stores in West Texas and Oklahoma. Larry is 35 and has been a buyer for 12 years. In the business he’s known as a big pencil, meaning that in a three-day period he’ll probably order upwards of $250,000 worth of merchandise. Salesmen jump when the big pencils show up. Larry flies to New York once or twice a year, to see a few plays and eat real Chinese food, he says, but does most of his buying in Dallas. It’s closer to home, friendlier, and much easier to shop than 7th Avenue. Besides, down here nobody mistakes him for a grain dealer.

I spot Larry near the escalator on the first floor. He’s dressed in a gray vested suit with discreet blue pinstripes, powder blue shirt, and black wing tips. He looks very businesslike, bankerish in fact. I’m dressed in gray slacks and a blue double knit jacket that was originally part of my wedding suit. Where fashion is concerned, I’d have to be considered unconscious.

I ask if wearing double knit will blow my cover.

“Grab a sandwich and let’s go,” Larry replies impatiently.

“I’ll wait for lunch,” I say.

“No lunch. We’re booked solid from 8:30 till 6.”

Already some of the glamour is wearing off the assignment. But I pass. I’m tough.

We start on the first floor, shopping for misses’ and junior dresses and ladies’ sportswear. The other buyers for Larry’s chain are taking care of lingerie, foundations, fake fur, and accessories.

We stop at Vicky Vaughn, where Larry has set up an appointment. A woman shows us to our chairs at the end of a long white formica table. There are probably 40 other buyers in the room, all sitting behind identical formica tables. All we need are bingo cards. Another woman brings us coffee. On my left are bowls of M&M’s and Karmel Korn, not what my body needs at 8 a.m. Larry tells me to be patient. The food will get better.

The regional sales manager usually works with the big pencils, but he’s sick today so we get one of the line girls. Most line girls are housewives who work for $25 to $35 a day, no commission, plus a chance to buy samples at up to 40 percent off wholesale. When the market is over they return, stylishly attired, to Piano and Richardson, and wait for the next one.

Our girl is pleasant but clearly inexperienced. She lifts each garment from the rack and presses it against her body like a decal.

“This one’s a big checker,” she assures Larry.

Larry doesn’t check it on his order form, or the next five styles either.

“Another hot number,” the girl says brightly, draping a long skirt slit to the hips across our table. Larry shakes his head.

“Our stores are surrounded by Baptist colleges,” he says politely. “Slit skirts aren’t big among Baptists.”

Like everyone else in the fashion industry, buyers are gamblers, torn between making the big hit and losing their shirts. If they buy solids when the world wants prints or stock up on pants suits when the trend is toward long skirts, they find themselves out of a job. Larry has survived because he knows his customers. He’s willing to nudge them, but cautiously. In Amarillo, straight-leg pants are acceptable, but slit skirts are trouble.

Undaunted, the girl works methodically through the line, pausing only to single out big checkers and those styles guaranteed, she says, to “blow down the door.”

“The phrase is ’blow out the door,’ ” Larry whispers when the girl’s back is turned. In the end he checks eight styles, an average number, but instead of turning in his order he slips it into his attache case. One advantage of buying in a supermarket is the chance to comparison-shop. Ten years ago a buyer might be limited to five or six lines in a given price range; now there may be as many as fifty to choose from. Before he submits his orders, Larry will look at up to twelve competing lines, comparing price, fabric, completion date, any of a hundred seemingly small details that can mean tens of thousands of dollars later. Salesmen complain that even though the Mart has increased the overall volume of business, their slice of the pie is getting smaller. Many have had to take on multiple lines just to stay in business. Buyers, for the most part, think this is just fine.

We go through the same procedure at a second junior showroom, where the fare consists of cocktail franks and tiny wedges of longhorn cheese. While I nibble, Larry checks, then once again stuffs the order form into his attache case. I wonder if I’m overlooking the subtleties.

Leaving the showroom, we’re confronted by a large balding man in a blue pinstripe,’who immediately grabs Larry by both shoulders.

“Come by and see me, Larry. I’ve got some goods you wouldn’t believe.”

“Still peddling those bubblegum dresses?” Larry asks.

“That was years ago,” the fellow laughs. “I’m up on three now. Imports. Italian silks. Beautiful goods.”

“Irv, I love ya,” Larry replies, finally pulling free. “So why the hell don’t you ship?”

Irv, Larry explains later, is a bad “resource.”

“He’ll promise you 100 pieces and he’ll ship 50. If you order stripes you’re likely to get solids or polka dots. I used to double my orders just to get what I actually needed, but it rarely worked. A week before the goods were due I’d get a call from Irv saying that his cutters were on strike or his shipment of Chinese silk was at the bottom of the Indian Ocean. He always had beautiful lines but you had to be nuts to buy from him.”

Not even the most reputable manufacturers cut every style that they show. Out of 200, they probably will produce 150. The so-called polka-dot houses get by on much less.

Markets are crucial in editing lines. If a particular style doesn’t check at least 30 percent of the time in Dallas, it will probably be dropped. As reports come in from Atlanta, Miami, Los Angeles, and other regional markets, the critical percentage may jump to 50 or 60. The salesman’s job is to try to anticipate which styles are going to be cut and push them, since unless he is working on a guaranteed commission from a manufacturer, and most salesmen aren’t, he will be paid his eight percent only on goods actually shipped. Good salesmen know how to protect their commissions. When they tell buyers that a style isn’t checking, they’re saying “Watch out.”

It’s now 10:30. Our next appointment isn’t until 11:15, so Larry decides to squeeze in another line. The showroom is packed and we don’t have an appointment. The girl at the desk asks if we can come back Monday afternoon or Tuesday morning. Larry has enough clout to bump another appointment but decides not to. “Maybe,” he says to the girl. “We’ll see.”

“Two years ago that company was nearly out,” he explains while we’re walking. “They made more money from subletting their showroom than they did from their lines. Now they’re hot and don’t have to bother with strollers. It’s a funny business. Monday morning somebody on 7th Avenue says that Ivy League is in and on Tuesday everyone shows up looking like a Harvard grad. How do you figure it?”

We pass a showroom that is deserted except for one salesman flipping through the Dallas News. The salesman waves feebly at Larry.

“Now two years ago that guy was hot. I mean hot. Then he got a couple of bad lines and the bottom fell out. Maybe he got mixed up with Irv. Like I say, it’s a funny business.”

The Apparel Mart is a maze of corridors broken up by several huge canyons of space. No matter where you think you are, you aren’t. The maps help, but the best way for a novice to find his way is to leave a trail of breadcrumbs.

Larry and I sprint to our 11:15 appointment, which seems several miles away. Are Adidas fashionable? I wonder.

1 know immediately that we’ve moved up because the food is better – prune Danish, ham and cheese finger sandwiches, a platter of petits-fours. And models, a measure of aspiration if not always success. Being a showroom model is considered a step up from being a line girl, and the better the showroom the bigger the step. A girl with some modeling experience can earn $50 a day, a model from Kim Dawson’s agency double that amount.

We plop into leather chairs, ersatz Eames but still very comfortable. No formica bingo tables here. There are only half a dozen buyers in the showroom, compared to 30 and 40 downstairs. The woman next to me is balancing a platter of what appears to be chicken a la king on one knee.

“The hot food’s out back,” she says brightly.

I decline, then pass her the petits-fours.

“Can’t, darling. I’m dietetic.”

The models begin strolling past in a variety of moods and poses. It’s like a beginning acting class with the garment as the text. This morning’s readings range from happy-go-lucky to sultry. Mostly sultry. The line is large, over 100 styles, so while Larry checks I chat with one of the models, a slender, oval-faced girl who might have stepped out of a Modigliani painting. Larry has told me that she’s headed for New York after the market.

“I wanted to go to Paris but the plane tickets never arrived,” she says. “We’re not allowed to go unless our expenses are paid beforehand, you see. Too bad, because next year I’ll be too old.”

“How old are you?” I ask.

“Twenty. And that’s old for Paris. They’re big on Lolita types over there.” She sounds disheartened by the situation. “But at least in New York I can work longer, especially if I lie about my age. Look at Cheryl Tiegs and Lauren Hutton. They’re both in their thirties and right on top. Lucky for me that I’m on the dark side. I can pass for Greek, Italian, Mexican, most of the ethnics. That’s a big plus in this business.”

She disappears for a few changes, then returns to resume the conversation. “Sultry is an easy look for me. So’s vampish. But I have trouble being enigmatic. 1 practice for hours in front of a mirror, but I can’t pull it off.”

She shows me her enigmatic look. She’s right. Totally transparent.

“What will you find in New York that you can’t find here in Dallas?” I ask. It is intended to be a leading question, but it makes me sound even more naive than I am.

“You’ve got to be kidding. Everything’s in New York!” Having put me in my place, she then becomes more thoughtful. “A model who’s any good at all wants to go to Paris or New York. That’s where the money is, where fashion is set. I want to know if I measure up. If I don’t, at least I know that I’ve given it my best shot. If 1 do, I might end up on the cover of Vogue or Harper’s. “

“That’s making it?”

“That’s making it.”

Our showing lasts until one o’clock. Larry is planning to meet with his other buyers before they start on their afternoon appointments. I decline to go along. I don’t care what’s happening in the world of foundation garments or fake furs. We agree to meet later in Group III, the couturier section on the third floor, then I go searching for my photographer, who I hope has seen something more interesting than checking. I find him, and a hundred other people, at the Funky showroom on II. Funky is to the other showrooms at the Mart what Minsky’s would be to a harpsichord recital. It’s a throwback to the earlier days of the Dallas apparel industry when, legend has it, things were looser and more eccentric. A chat with a veteran salesman invariably leads to stories about mynah birds and performing monkeys, television giveaways, and expense-paid trips to the coast to see a new line. One salesman, to push his line, floated a hot air balloon over the Mart parking lot. When the management objected, he rented a dozen Volkswagens, equipped them with roof signs, and parked them at key points around the building. When police started turning the cars away at the gate, the salesman had the signs cut so that they could be folded flat. Once the cars were safely on the premises, they popped up again magically.

Such ingenuity is rare these days. The Mart discourages body snatching and promotional gimmicks, though the opport unities are still there for the truly committed. Larry claims that the best he’s done in ten years is a few bottles of Ara-mis and a set of mismatched cufflinks. No Swiss watches or Caribbean cruises. The times have changed, he says. The industry has grown up. Salesmen spend their time reading the Wall Street Journal instead of thinking up gimmicks. What few there are can be found among the marginal budget lines, the so-called polka-dot houses, whose lifespan is about one market, and even they would rather have a product that they could sell.

At Funky, disco dresses are the style and décolletage is the theme. While models stroll seductively down a runway, a Funky salesman, Scotch in hand, shirt unbuttoned to the waist, delivers his ironically sexless patter.

“Style 124, a winner at $19.75. Available sizes 6 to 14 in tea, oatmeal, wet sand, and ravishing midnight black. Big reorders on this number.”

The look here is a combination of sexy and vampish, with just a touch of Cedar Springs. Judging by the number of faces pressed against the glass, the line is going to be very popular.

The photographer and I slip inside and begin shooting over the heads of the buyers. A burly fellow in a tan leather jacket walks over and asks who we’re with. We tell him D Magazine. He hesitates, obviously trying to place us among the trade papers.

“The magazine of Dallas,” we add.

“Fashion?”

We nod.

“No offense. It’s just that we get a lot of knock-off artists coming in here.”

While the photographer shoots, 1 help myself to some smoked turkey, more from habit than hunger.

One of the models looks over at me and asks what kind of film the photographer has in his camera. I tell her black and white.

“This dress will look like hell in black and white,” she responds, and ducks behind a curtain.

At 2:30 Larry and I meet in Group III, the penthouse section of the Apparel Mart. All the name designers are located here – Bill Blass, Calvin Klein, Mollie Parnis, Albert Nipon – as well as most of the higher-priced couturier lines. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar at last. The corridors are carpeted, the formica and plastic of I and II have given away to leather and natural fibers and clusters of ficus trees. There’s less talk of “checking” and goods “blowing out the door.” Business is done discreetly, with a certain savoir-faire missing in the bodysuit market.

We’ve arranged for a private showing of designer sportswear. These showings are customary for the big pencils like Larry, while Mrs. Jones from Balch Springs, with her ten-piece order, will have to squeeze into whatever slot is open.

Cheese, fresh fruit, and liver paté from Wall’s are waiting when we arrive, along with a carafe of white wine. Individual outfits have been carefully arranged on tables and sofas, like fine drawings: an oatmeal top with a seawood bottom, lemon meringue pants with a fitted avocado jacket. Julia Child might have designed the line.

Larry introduces me to Howie, whom he describes as the best old-school dress man at the Mart.

Howie laughs. “Hell, I’m just a regular Jewish kid who wanted to go into show business and ended up selling rags. Nothing special about that.”

Larry doesn’t let him off so easily. “Tell my associate here about your days up in Minnesota.”

Howie laughs again. This is clearly a set piece that he enjoys doing.

“I went on the road at 19 with a line of handkerchiefs. Had to get permission from my father, who wanted me to be a lawyer. Anyway, my territory was Minnesota, Wisconsin, North and South Dakota. Imagine trying to sell handkerchiefs in South Dakota in the winter. Here I wanted to be on the road and the roads were always closed. So I said to hell with that and went to the coast. 1 sold pants, blouses, swimsuits, anything. All a salesman really wants is his own line, right? Hell, I had a line a month.”

“How many do you think you’ve had?” I ask.

“Fifteen, twenty,” Howie says. “Who knows? Anyway, that was before I got smart. There are only four things you have to ask about any line: Can I sell it? Will the stores buy it? Can they sell it? Will I get paid? I was good on the first three and lousy on the fourth. 1 worked for a lot of thieves and liars before I got smart. Take my advice and stay away from the polka-dot houses. The Chinks too, unless you can’t avoid them. You can’t do better than the old U.S. of A.”

Because this is a private showing, Larry doesn’t have to look at the entire line. He can break it up and look only at the pieces that interest him. If he wants to see a garment on, a model shows it. Between fittings, he and Howie putt plastic golf balls into a coffee cup at the far end of the showroom.

“Got money on the game today?” Howie asks both of us.

We shake our heads.

“I’ve got three C”s on the Cowboys. With all the commission I’m going to make on this sale it won’t matter if I lose.”

When we’ve looked at about 20 styles, Larry turns to me and asks how many pieces we should buy.

I hesitate. This wasn’t part of the agreement. “A hundred,” I mumble nervously.

“Better make it 125,” Larry says immediately.

“You can get by with 110,” says Howie.

An assistant quickly figures the ticket on 110 pieces. It comes to just over $14,000.

Larry nods, as though bidding at a silent auction, and we all have another glass of wine.

“You’re getting into a great business,” Howie tells me as I’m leaving. “David Merrick has one, maybe two openings a year. I’ve got five. And I’ve never slept the night before. I love it.”

The high points of the market are the fashion shows, which range from the y’all come 7 a.m. manufacturer shows, in which any manufacturer willing to pay $60 a garment can be represented, to the Saturday night spectaculars like the B.A.M.B.I. Flying Colors Awards (a clumsy acronym for Buyers Apparel Mart, Braniff International), featuring the buyers’ favorites. The Dallas Mart was the first to provide fashion shows, lectures, and seminars for buyers. The management insists that they are one of the major reasons for the market’s mushrooming popularity. Salesmen complain that all they do is keep buyers out of the showrooms for several hours each day. Regardless, the other primary regional markets (Atlanta, Miami, Chicago, Los Angeles) are following Dallas’ lead, though to a less extravagant degree. The average Saturday or Sunday night show costs about $30,000 to produce. Sets have to be designed and built, special lighting and sound equipment installed. Choreographers are flown in from New York and the west coast, sometimes accompanied by starlets who used to be models and are now making it big on The Wheel of Fortune and The Dating Game. The B.A.M.B.l.’s are the Academy Awards of the Dallas fashion industry, minus the suspense: The winners are always announced beforehand so that they can capitalize on the publicity during market.

Models compete to be in the big runway shows, not only for the $150 fee for a few hours’ work, but for the chance to perform before 5000 people, among whom might be the scout with the airplane tickets to New York or Paris. The “star pieces” are coveted, and every girl has to reach deep inside for her most convincing looks. From runway to the cover of Vogue in ten quick changes. The fact that very few models ever actually make the trip doesn’t diminish the power of the fantasy.

The B.A.M.B.I. awards are held in the Great Hall, a giant hollow of sculpted cement and white plaster that was one of the sets for Logan’s Run and seems to epitomize the surreal quality of some aspects of the fashion industry.

Larry and I arrive a few minutes before seven, just as the North Texas State Lab Band is finishing its rehearsal. 1 head instinctively for the table marked “Press,” until Larry grabs my arm and steers me toward a larger table at the end of the runway.

We plop down beside two buyers who are pecking away at their pocket calculators.

“I think we’re too heavy in 2804,” the first one says. “That body just isn’t us.”

“I’m easy with 2804,” says the second, “It’s 3150 and 3160 that worry me. The trim is terrible.”

“And the colors. Is anybody going to buy champagne or toast?”

Across the table is a fellow from one of the British fashion publications, who’s visiting Dallas for the first time. 1 resist asking him what he thinks of Texans. I’m more curious about what he thinks of bourbon, which he’s downing in great gulps as though it were iced tea.

Before I can inquire, the lights dim, the music comes up, and the awards presentation is on. Designer dresses come first, followed by sportswear, outerwear, lingerie, misses, ten lines in all. That’s a lot of interpreting in a short period of time. The readings tonight range from chic out-doorsy, sort of a blend of L.L. Bean and the Champs Elysées, to vampy, to what one buyer refers to as Beverly Drive hauteur.

I watch for my model friend from the showroom. I spot her first in a white wraparound coat with a fur collar, looking like an ad for some Scandinavian tobacco. Moments later she’s back as a vamp, then as a sexy girl next door, then the lady from Beverly Drive. The last is definitely not her look. I keep waiting for the enigmatic pose but never see it. A model has to recognize her limitations.

After each presentation, the winning designer is trotted out to receive his statuette. Winners thank the mart, the models, the buyers, their mothers. The Master of Ceremonies thanks the designer and the choreographer. Everyone is very grateful. In between there are unsolicited testimonials for Braniff, the Concorde, and the Anatole (not yet open).

“Who’s Anatole?” asks our British friend, who at this point is somewhere in the Lake Country.

Nobody answers.

Forty-five minutes into the show, Larry leans over and whispers that he’s had it for the day.

“We going to a party?” I ask. A chic blow-out seems like fair compensation for a hard day of checking.

“If you find a good one give me a call,” Larry says.

I mention dropping by the Marriott or checking out the action at Papagayo, supposedly a big favorite with the fashion crowd.

“I’ve all I can do to make it back to the Registry. It’s terrible what this business does to youth.”

“You in leather?” one of the buyers asks. “The leather crowd always stays at the Registry.”

“Fabrics,” says Larry, rising slowly.

Several people call his name as we head for the door, but we keep on pushing.

“See you tomorrow?” Larry asks.

I hesitate, wondering if perhaps I have enough material. But after Irv and Howie, what’s enough?

“Sure,” I say.

“Good, 7:30 at the escalator. And do me a favor. Wear something besides that double knit.”

Related Articles

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert

Things to Do in Dallas

Things To Do in Dallas This Weekend

How to enjoy local arts, music, culture, food, fitness, and more all week long in Dallas.

By Bethany Erickson and Zoe Roberts