We suspected that the trip wouldn’t go according to plan the moment we tried to make plane reservations from Guatemala City to Tikal, the ancient Maya center in the heart of the Peten jungle. It is the Rome of the Maya world, and we’d been waiting ten years to see it. The Aviateca agent assured us that, yes, planes flew to Tikal and, no, advance reservations were out of the question.

“What are we supposed to do?” we inquired.

The agent stared at us, as though we were joking with him. “You get out of bed, you go to the airport, you buy a ticket, and you leave.”

“And what if there aren’t any tickets left?”

“Then you wait till the next day,” he shrugged. “What else?”

Waiting, we quickly discovered, is a fine art in Guatemala, like queuing in England. As a tourist you either learn to shift down from fourth to first or you spend a lot of time grinding your teeth. Guatemalans enjoy sipping coffee, haggling at market, taking halt the morning to get their shoes shined. Buses don’t run on schedule because promptness is considered a joyless virtue. Conversation and eating and bartering are what really matter. Bus signs that read “40 pasajeros solamente” are merely crude estimates usually off by at least half.

We waited the first night in the Hotel Pan American, located downtown near the National Palace and the central market. There are more fashionable hotels on the outskirts of the city, but the Pan American has the kind of fin de siècle charm that you read about in the novels of Maugham and Greene. Ceiling fans rotate lethargically, a blue macaw chatters to himself while eating an orange, waiters in gaucho pants and brilliantly embroidered shirts patter about with trays of coffee and fresh fruit. It’s easy to imagine the early explorers like Maudslay and Sir John Stephens stopping here on their way to Tikal. We positioned ourselves among the potted jade palms, sipping warm Gallo, while mini-buses decanted groups of German schoolboys and Irish nuns into the lobby. Some had come to see the ruins, others were only stopping on their way to the highlands to buy weavings. The city markets were overpriced, one couple told us. For the best buys one had to travel to Chichicastenango and San Antonio, where the women still worked on hip looms and all the designs were indigenous.

As advised, we went to the airport at dawn, uncertain how many planes would be available. This morning there were two, both DC-3’s that might have seen service in the Burma campaign. We sprinted for the one with the freshest paint and got seats next to a smiling Quiche Indian, probably on a visit to his native village. Like many other passengers, he was cradling a styrofoam jug of water. When the plane lifted off, we discovered why: The air conditioning didn’t work. Every few minutes our companion would soak his neckerchief in water, lean back, and sigh contentedly as it fell onto his face. Here was a traveler’s tip you won’t find in Fodor.

Now and then our companion would glance at the mountains floating past the window, solid blocks of green accented occasionally by a road or an open field, and whisper “GGA, GGA.” It was several days before we learned that GGA was the acronym for the Guatemalan Guerrilla Army. In response to the latest, and by most accounts rigged, national elections, the GGA had become more aggressive: slipping into cities at night to sabotage telegraph lines and police barracks, then disappearing back into the hills during the day. Among the natives, the Guerrillas had a certain folkloric standing, like the James Boys, so that whenever a road was closed or a train was late, you’d hear rumors about the GGA.

The flight to Tikal took an hour, though the heat made it seem like ten. By the time our plane bumped down on the grass runway we felt that we were already acclimated to life in a rain forest.

We were met by a slender man wearing a straw hat, jeans, and a faded Adidas T-shirt. He said his name was Jose and that he would like to be our guide. At first, my wife and I hesitated. We dislike being led around, even in the jungle.

“Tikal is different,” Jose persisted. “There are things here that you can’t discover on your own.”

His confident, matter-of-fact manner convinced us to go along. We joined about a dozen other tourists on a causeway leading to the great Central Plaza of Tikal. Ahead we could see the tops of pyramids and the double roof comb of the Temple of the Giant Jaguar, probably the single most famous structure in the Maya world. This was what we’d waited ten years to see.

Yet for two hours we moved no closer to the plaza. Jose didn’t mention pyramids and deflected all questions about them by saying that we had to understand other things first. He explained the Mayan counting system, a dot for 1, a bar for 5; he drew elaborate glyphs in the dirt with his walking stick, translating each one into a brief narrative as he went. At one point he made all of us get down on our hands and knees to examine a group of figures cut into a halfburied stela. The most prominent were a priest in a feathered headdress and what appeared to be a captive with a rope around his neck. Someone asked why the Maya always sacrificed their captives.

“They didn’t,” Jose replied. “That’s Hollywood Maya, cowboys and Indians. You will learn.”

It was clear that we weren’t getting a canned Six Flags-style recitation on the wonders of Tikal. Jose’s knowledge was detailed, intimate, and, one began to suspect, instinctive.

Walking toward the plaza, he mentioned that he’d worked with the archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania, which sponsored many of the major excavations at Tikal; now he was working with the Guatemalan government, though little actual field work was being done

“We can’t protect what we already have,” he said. “Objects are disappearing all the time. Of course, sometimes the looters disappear as well.”

By the time we reached the Great Plaza, a two-acre complex of pyramids, residential palaces, altars, and ballcourts, our group was down to four. This didn’t bother Jose. He seemed to be talking as much to himself as to us anyway. He inquired about other Maya sites we had visited. We told him Uxmal, Chichén Itzá, and Kabah in the Yucatan. We also described a day-long jeep trip to the ruins at Sayil.

“You must go to Uaxactún, then,” he replied. “It’s very close. You can walk there in a day.”

“How far is it?” we asked.

“Twenty-four miles,” Jose said, swinging his arm in an easterly direction. “I used to go there once a month, but now I’m not strong enough.”

Most of the time Jose trotted on ahead of the group, talking over his shoulder, but on stairs we noticed that he held back to catch his breath, disguising his discomfort with jokes about being too old for the job. He couldn’t have been more than 30.

Very slowly, he led us up the nearly 200 steps of the Temple of the Giant Jaguar, the highest temple-pyramid in the New World. Built in the late 7th century, it commemorates the accession of Double-Comb, one of the great rulers of Tikal. As we reached the top, the sun was setting behind Temple II, erected in honor of Double-Comb’s wife, so that for a few moments the horizon resembled a gigantic studio drop. As though on cue, green parrots, invisible during the day, now swooped across the plaza in large chattering flocks, accompanied by toucans, macaws, and other exotic species we’d seen mainly in zoos and the books of Roger Tory Peterson. A pileated woodpecker hammered away on a dead tree, while down below several agouti began rooting about in the underbrush. With most of the tourists gone, and the Great Plaza given back to the animals, one got a sense of Tikal as truly a world apart, unlike anything but itself. At its height in the 8th century, it was a major ceremonial and trading center dealing in jade, obsidian, flint, textiles, and agricultural products. As many as 40,000 Maya may have lived in an area of 50 square miles. No one is sure why Tikal declined so rapidly after about 890 AD. Disease, wars, a peasant revolt against an insensitive ruling class, all these may have played a part. Jose was partial to the revolution hypothesis.

“Governments always take too much,” he’d say. “There’s never anything left for the people.”

Accommodations at Tikal are simple and rustic: one motel located near the tip of the runway and a group of small, palm-thatched huts set back in the jungle. There is running water, which nobody drinks, and electricity every evening from 6 to 10 when the overnight guests gather for dinner.

The communal dining room occupies half of a long frame building; the other half encompasses a makeshift bar with a few tables and chairs. Each night we were in Tikal, the same group assembled: a Guatemalan woman and her American husband, who did little more than groan and pop Lomotil; a young English couple dressed entirely in white, like characters out of a Fellini film; the wife of an AID official in Guatemala City; Jose, and us. The meals were simple; baked chicken, black beans and rice, maybe a slice of melon or a fried plantain for dessert. Tea for those who would risk the water, beer for everyone else.

Conversation was relaxed and surprisingly personal considering the only connection we had with one another was Aviateca. The wife of the AID official filled us in nightly on the problems of living in a place like Guatemala City. It was better than Sao Paulo, of course, where you couldn’t get a decent doctor; and a dream compared to Santiago, especially after the Allende business. But still, you had to put up with a lot: You had to stay close to the American sector at night, you had to keep your children in American schools, milk was hard to get, old friends never dropped by for a visit.

“And you’re always having to decide about whether to keep your diplomatic license plates, which help at the borders, or get Guatemalan plates so you’ll be less conspicuous. I’m still looking for the glamour.”

Most of us found the AID wife intriguing, a not-so-ugly American trying to make sense of a way of life we know about only from spy novels. Tikal was her rest cure. Jose never responded to anything she said, whether out of contempt or indifference it was impossible to tell. His subject was always Tikal; after a few beers, he spoke of the odd people who came there. He took special pleasure in telling us about a Texas oilman who, as often happens in Tikal, had been bumped from the afternoon plane back to Guatemala City. The Texan demanded a private plane be brought in. Jose explained that it was impossible, that he had no telephone, only a short-wave radio. The best thing to do was wait until the next afternoon.

“I told him it would cost at least $800,” Jose continued, holding up eight fingers so that we could all measure the extravagance. “He said he didn’t care, he was going back to Texas. So we had to get him the plane. It arrived just before dark. We turned on the headlights of all the trucks so it could land. People from Texas must be very strange.”

Through all of this, the couple in white said little except that they’d come from London to Guatemala for health reasons. The illness was never specified, though for purely literary reasons I hoped it was consumption. During the day we’d see the husband, immaculately attired in white pants and shirt, taking photographs among the ruins. If he’d had an 8 x 10 camera and a white beard, he could have passed for a field photographer in the Maudslay expedition. His wife spent most of the day in her room, writing poems. She promised to write one for each of us, but we must have been elusive subjects because only Jose ever received one, rolled up like a scroll and tied with a length of gold ribbon.

After dinner, everyone drifted to the bar at the far end of the building, ordered a lukewarm Gallo, and waited for the animals to appear. Which they always did >- deer, foxes, agouti, plump wild turkeys that looked like caricatures of themselves. Observing the scene from behind screen windows, we realized who really possessed Tikal. Tourists were simply interlopers, allowed in for a few months each year to amuse the animal population.

Each morning, before the DC-3 arrived from Guatemala City, Jose went off on hikes into the rain forest. They had nothing to do with work. They were strictly personal excursions which anyone was welcome to join. Having grown up in a village close to Tikal, he knew all the trails by heart. He’d hunted puma and jaguar here, though now their numbers had been so reduced that one rarely saw one anymore. That situation saddened him visibly.

We spent most of one morning follow-ing a column of carpenter ants to where they were methodically stripping a bread-fruit tree of leaves. Overhead, packs of spider monkeys swung noisily through the top branches, dropping lower on occasion to get a better look at these intruders. Jose explained that they were probably at-tracted by our mosquito repellent which, like proper Texans, we had bathed in before starting out. “It gets them excited because it’s so unnatural here. Best to rub it off.” We did that.Another morning we stood beside a pond near the park workers’ compound, waiting for a solitary crocodile to surface. Nobody at Tikal remembered where he’d come from or how long he’d been there. Not that it mattered. He was a given, a part of the landscape, a presence which everyone acknowledged.

These treks always stopped when the first plane appeared overhead. In only a few days we’d grown to resent the sound of propellers, as though it violated our own private space. We knew it was presumptuous to think so, but we did it anyway. Before leaving, Jose would draw a map to one of the more remote sites, sometimes only an anonymous black dot in the official guide, and tell us to pay special attention to the lintels or the graffiti or the stelae or whatever he thought was important.

Each night at dinner, Jose took his seat at the end of the long refectory table and began asking questions, like a college professor putting graduate students through their paces. What did we think of the lintels? Had we noticed the patches of original paint on the ceiling? Could we decipher the stelae? He’d show us a stela that even the best scholars hadn’t deciphered. Had he deciphered it? Certainly. Had he told the scholars? He wasn’t a scholar; they wouldn’t listen to him. It was clear that he didn’t care about their approval. He had made sense of Tikal in his own way. If others agreed, fine. If not, no matter.

He mentioned one evening that he was a writer too, not a professional, of course, just an amateur. He had recorded all the stories and legends of his home village. I asked if I could read them, not even thinking that they might be in some inaccessible native dialect.

He smiled and said that he’d given his manuscript to a man from Los Angeles, who had promised to find a publisher for him. That was two years before and he’d heard nothing.

“It doesn’t matter. I have the stories in my heart and repeat them to my nieces and nephews. They won’t go away.”

This was usually how you discovered things about José-indirectly, obliquely. He didn’t volunteer much information.

Except once. Near the end of our stay in Tikal, six of us were seated in the bar, sipping warm Gallo and waiting for the animals. The wife of the AID official had gone on to Uaxactún, nobody knew exactly how, and her place was taken by an archaeologist from Germany who, like us, had bathed himself in insect repellent. We could almost taste it in our beer. Jose told him about the monkeys. The archaeologist laughed and said that the idea was absurd. Jose smiled back and said that he might change his mind.

During the conversation, we noticed that Jose was massaging his right side, as though trying to work out a cramp. He said it was nothing, just some scar tissue acting up.

“The GGA got me,” he said.

Nobody laughed.

“Almost the truth,” he added. Then, without being asked, he lifted his T-shirt and exposed a deep red slash extending from his right shoulder blade to his navel.

“See,” he grinned, slipping back into his chair. One night, he continued, he and three archaeologists were sitting on the steps of the main building, almost where we were then, when a man came stumbling up the path toward them. At first they’d suspected that he was a looter, then realized that he was drunk. One of the archaeologists had asked, jokingly, if he was from the GGA. The man grunted, sat down on the porch, and asked for a beer. José refused. Then, without warning, the man drew a gun from inside his shirt and fired it at Jose, hitting him once in the forearm and once in the abdomen. As soon as they’d subdued the gunman, the archaeologists put Jose in the bed of a pickup truck and drove him forty miles through the jungle to Flores, where doctors removed a kidney. That had been four years before. Now the other kidney was beginning to fail.

“The doctors say that within two years I’ll have to move to Guatemala City so I can get dialysis. They say I’ll die if I stay out here. I know I’ll die if I have to go there.”

That was the last time we spoke with Jose until we were about to leave two days later. Had he spoken too freely about his personal life, violated some private code that made him ashamed or angry? There was no way to tell, and we knew that we could never ask.

Just before leaving, we slipped into the small museum at the end of the runway which displayed the usual maps and explanatory diagrams, as well as exquisite funeraries and mosaic masks of jade, pyrite, and shell. As we were looking at one mask, Jose walked up to us, smiled, and said that he was sorry he hadn’t seen us the day before. He’d been busy. He promised that when we returned to Tikal he would show us some jade that was just as beautiful and not so well known.

We nodded, adding that of course we didn’t know when that would be.

“That doesn’t matter,” Jose replied. “Tikal will be here.”

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

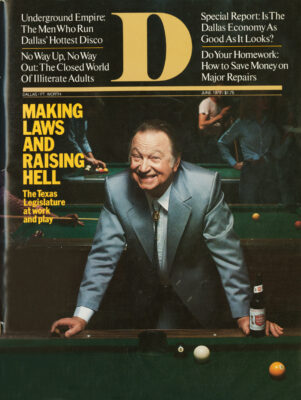

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte