It is a Friday evening and Jim Bond and I are three hours deep into an interview. There are thick file folders spread over the couch and coffee table; some of them have spilled onto the floor during flurries of shuffling and debate. Jim Bond is talking hard, making this encounter, like previous ones, impossible yet full of information. When he isn’t talking, he’s yelling; he’s swearing; he’s laughing; he’s waving his arms and stamping his foot.

“Get me Joe Abbeeeyyyy!” he yells to his secretary in a tone and vibrato reminiscent of Costello’s call for Abbott. “Damned lawyers!”

We talk about the Dallas Civic Opera again, which under his leadership was plagued by internal battles and mounting debts to banks once connected with Bond. “Whooaaa! Whoaaa! Oh yeah, oh yeah, I’ve heard that before – at the end of my term the opera finds itself $1 million in debt. Sure! Sure it was! But to who? To me! That’s who! To ME!

“My God, when the orchestra has a $67,000 payroll to meet, the curtain is about to go up and the orchestra’s saying it won’t play, you think I’m gonna placate some of those flat-chested women and hundred-dollar contributors? Well you’re wrong, dammit!

“Pat! Get me the Opera file,” he shouts.

“Which one, Mr. Bond?”

“Everything!”

Thumbing through the correspondence and audits, he continues to make random reference to unknown characters. “Here, look at this – oh, ohhh, damn, here’s another.” He keeps turning the pages. “They’re so wrong and I feel sorry for them.

“Get me Abbeeeyyyyy!”

In a minute the phone buzzes.

“Hello, Joe? I need to know about that DIB IDallas International Bank] settlement, you know, the agreement you drew up when we had a washout. Now, there’s no 16-B violation or never was any of that – now, what was that agreement about?

“Yes, he’s been digging around, and I just need to tell him that the thing was completely settled and that the bank owed me.” He hangs up and looks my way.

“I was worth nearly a million dollars to that damned Opera, and there were a few of them [directors] who were always bitch-in’ an’ yackin’. Well I never gave ’em the time of day. Piss on ’em!”

And so goes our interview, for five and one-half hours. It is a maze of statements and denials, attempts to placate and attempts to intimidate. Jim Bond has dug his heels in on every point dealing with his checkered history of fund-raising and management of non-profit enterprises. He knows the real point of the interview is to figure him out, and by extension, what he’s doing today with his most recent project, the Foundation for Quality Education Inc. – the special non-profit corporation he runs for the Dallas Independent School District – and Eastern Gateway, its proposed downtown educational highrise.

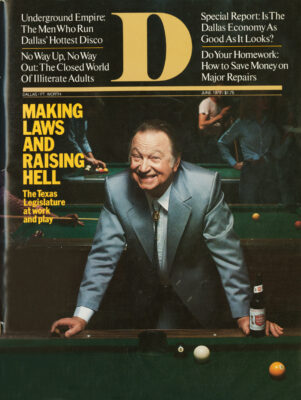

Bond is accustomed to argument; he has been at this kind of thing for a long time. He headed the mammoth regional office of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare for 20 years, and began fund-raising work in Dallas before 1959, when he captured the city’s most prestigious honor, the Linz Award. At 73, he is as lucid and mean as ever.

Despite questions about the propriety of his most recent project, Jim Bond is not frustrated. On the contrary, he is fiercely promoting Eastern Gateway.

It puts a special edge on our interview. What does he think of the school board members? “A bunch of meatheads.” What about people who opposed Eastern Gateway? “lronheads.” Then we talk about Jim Bond. What gets him so riled up? Questions. Plain and simple: Questions. “Boy, when I’m working on thesedamn charities, I don’t apologize to nobody. I don’t take any shit. I speak mydamn mind. And I do what I damnplease.” :

James Bond has built a remarkable , career of civic prominence through such tough-talking salesmanship. It carried him far beyond his high school education to the upper echelons of the regional federal bureaucracy and the chairmanships of more major charities than any do-gooder in Dallas history. It carried him to the board rooms of the city’s largest businesses and the ballrooms of its , finest country clubs. It took him from a ’ civil service salary of $166 per month plus expenses to impressive wealth and a spendthrift lifestyle.

Through it all, James Bond has sold one thing above all else: himself. Whether pushing federal poverty programs as head of the regional HEW office, or donations to the United Way or the Civic Opera or the dozen other major charities he has headed, Bond has always sold Bond.

But where the Foundation for Quality Education is concerned, the sales pitch sounds stale; Bond’s remarkable energy and drive seem to have reached a point of diminishing returns.

Like other legends in this young James Henry Bond just kind of appeared one day. The son of an Oklahoman banker/rancher father and a New Yorker socialite mother, Bond grew up in two worlds: One of hard work and isolation on the ranch in Minco, and one of old Eastern wealth on frequent trips home with his mother.

His schooling was brief – four years at a prep school near Princeton, New Jersey, ending in 1923. After working in the wheat fields of West Texas during his late teens and following the harvest to Kansas, Bond roughnecked in the oil and gas fields back home in Oklahoma. In 1931, he spent 90 days at a now-defunct law school in Lebanon, Tennessee. Then he came to Texas to take the Civil Service exam. He did well and began working for the U.S. Employment Service in Austin in 1934.

The state and federal bureaucracies were not unfamiliar to the young Bond; his uncle, Reafer Bond, had been the Oklahoma Corporation Commissioner, in charge of regulating gas and oil for the entire state. Bond progressed rapidly and began attending functions at Governor Lee O’Daniel’s mansion in Austin. That is where he met his wife of 35 years, the former Elizabeth Lacy of Longview. It was a marriage of social note: Elizabeth is the daughter of Edmund Lacy, a prominent East Texas lawyer whose family fortune was derived largely from gas and oil interests, as well as from farming.

Jim Bond’s government career was soon on a meteoric rise. He came to Dallas in 1941 to work for the War Manpower Commission, put in a brief tour for the same agency in Washington, D.C., and ultimately wound up in Dallas, heading HEW in Texas and four neighboring states – an agency that by the mid-1960’s put Jim Bond in charge of 5000 government employees and welfare spending of more than $1 billion a year.

But it wasn’t his government service that made Jim Bond a leading citizen. It was his affiliation with the indefatigable Fred Lange, whose own career in philanthropy took him from the streets of San Antonio, where he worked for the Salvation Army, to the Fred Lange Center in Dallas, where he manages the $35-million Community Chest Trust Fund.

Bond hit it off with Lange right away: Both men liked a good laugh and both were persuasive, compelling speakers. Lange was the rough-and-tumble preacher’s son from Jersey City, New Jersey, and, in a way, he and the Oklahoman were outsiders to the rrch and wealthy. But they both played a hard game and never apologized when working for a good cause.

Civic and charity work came naturally to Jim Bond. He would eventually become president or chairman of the March of Dimes, Planned Parenthood of Dallas, the Dallas Council of Social Agencies, state chapters of the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association, and many others. Fund-raising was in his blood, and his front-running style and contacts made him an asset to any charity group. Dallas rewarded Bond lavishly: Editorials trumpeted his energy and “civic contributions”; over the years, he has received 204 plaques and citations, including the Linz Award.

In 1962 Lange tapped Bond to take a leading role in the first United Fund of Dallas, later to become the United Way. In those days, says a leader in philanthropy, “to be made a leader of something like the United Fund was to be made a community leader.” Bond still believes that, too: “Hell, I bet Fred made 15 people into first-class citizens,” he says. “Look what he’s done for Russell Perry!” (Perry is the president of Republic Financial Services, currently heading up Lange’s trust fund.)

The Lange-Bond alliance served both men well for 20 years. During the 1960’s, Bond nominated Fred Lange to serve as the nation’s emissary for Community Chests under Lyndon Johnson. In 1970, Lange named Bond president of the trust fund. And Bond, during his lengthy term as president of the Dallas Civic Opera, made sure ]Lange became a man of the arts by making him a member of the Opera’s board of directors.

“They made a pact way back around ’60,” says a former associate of Bond’s, “that Lange would make Bond a community leader and Bond would bring Lange into the arts.” To this day, Bond says, “Everything I know about fund-raising I learned from Fred Lange.”

It was predictable that Bond, a man of immense energy and verve, would also apply his talents to private enterprise. With dizzying speed and success, he became involved in banking, real estate, investments, oil and gas. His enterprises became so large that his secretary at HEW kept two calendars for him: one for Jim Bond the civil servant; the other for Jim Bond, the private conglomerateer. By 1966, the civil servant was also chairman of the board of the Bank of Services and Trusts (now Dallas International Bank); vice chairman of the National Bank of Commerce; a member of the board of directors of Ling-Temco-Vought Corporation (which had major government contracts); president of Haas and Haynie Investment Corporation, a real estate development company operating in California and Nevada; chairman of the board of Electro-Science Investors Inc., a Richardson holding company; a board member of Tamar Electronics Inc.; a principal of Bond-Lacy Oil Company of Longview; a member of the executive committee of Exchange Savings and Loan Association; and a member of the advisory boards of Wynnewood State and Trinity National Banks. Besides his government office, Bond kept two offices in LTV Tower: on the 18th floor, where he ran Investment Bankers Inc.; and on the 31st floor, where he ran Kendall Realty Corporation and High Rise Inc.

Jim Bond became a man about town, known for his style. Not only was he a friend of Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson, he ran with the likes of Jim Ling and Troy Post – two of the city’s all-time entrepreneurs. He was known for his wit, his charm, his whimsical spending; and he was known for taking flamboyance, extravagance, and attention-getting to new extremes.

A classic Bond tale involves his friend Dolores Elkins, who had complained that she could never find a parking spot downtown. Bond suggested they have dinner with two friends at the City Club. That night, on the way to the City Club, Bond instructed Ms. Elkins to drop by the Fairmont for a moment so he could pick something up. Predictably, she complained that she would be unable to park. Bond told her to drive into a delivery alleyway at the rear of the building. The car, with the four of them in it, wound up on the freight elevator and was lifted into the hotel. The doors swung open to a vast ballroom, empty except for a table set for four, three violinists, and dozens of NO PARKING signs.

Without a doubt, Bond’s best society party was in January 1969, at the Brook Hollow Golf Club, under the membership of Leo F. Corrigan, founding chairman of the Dallas Civic Opera. Bond, his wife, and two daughters were honoring three debutantes. Florists spent two days setting up in the main ballroom and under outdoor tents. Denny McLain, the Detroit Tigers pitcher, brought his quartet for music; he played alongside the Righteous Brothers and two other big-name bands. There were cheeses constructed to look like ships under full sail, a pig with an apple in its mouth, glazed duck in aspic, oysters on the half shell, lobster meat wrapped in bacon, pate de foie gras, prosciutto and melon. It was an arresting presentation of pleasure: food, music and a thousand happy people. The price was arresting as well: $120,000. Bond couldn’t have been more pleased. The party was a symbol of his position in society.

Even as Bond was building his reputation as a leading citizen, he was quietly building another – one that was shared among only close associates and one that Bond today tries to keep secret. It is reflected in the minutes of board meetings, in the columns of financial reports, in the file folders of the county courthouse – and in the recollections of some of Bond’s former co-workers and associates. It is the contradiction of Jim Bond – that a man of such purported leadership and business ability would in fact bring internal chaos and divisiveness to some of his biggest civic efforts and, in his private dealings, manage money in a way that would bring financial collapse to him and huge debts even to his closest personal friends.

Interestingly, the administrative bungles began as early as 1962, even as Bond was riding the crest of his civic prominence. Bond would receive the obligatory plaque for his services as United Fund campaign chairman that year, but he would leave behind a legacy of gratuitous administrative meddling.

Internal problems began as soon as Bond took charge of the campaign. He could not be reached when there were questions from staff members. When he was available, he would talk only in gen-eialities; when he was specific, he failed to follow through. “He just flitted all over,” says a man who played a critical role in that drive. “He just couldn’t stick to his own duties. He got involved in everybody’s jobs, and he even became involved in staffing. The man had no conception of detail, and he wouldn’t follow through. When there were things that needed to be attended to, he was not available. There was smoke, confusion, and unmet tasks.”

Another campaign worker had figured his own personal strategy on how to work around Bond, whom he viewed as an impediment. “If he obstructed what I was doing in some way, I’d just take an end run around him.” Did Bond object? “Oh no, he wouldn’t know it. Anyway, anything was okay as long as he got all the glory.”

Bond did get all the glory, despite the fact that the campaign was postponed two weeks because his work was not completed on time. The fund collected $4.6 million, $588 over the goal. But there were apparently serious questions about his competence: In its 17-year history, Bond is one of the only two campaign chairmen who did not assume the presidency the following year. (The other was Robert Cullum, who was unavailable after his appointment by Mayor Thornton to head up the Dallas Assembly.) “After the campaign, when there was talk of who would be president after that, Bond was never really considered,” says one source. “He’s a well-meaning guy, but he can’t and won’t follow plans through.”

It was his 12-year tenure as president of his prize civic project, the Dallas Civic Opera, that would most clearly reveal the two faces of James Bond. While Bond continued to consider it “the Bond opera,” concern developed within the organization about lavish spending, poor accounting practices, and mounting debts during his dozen-year stint.

By 1971, a few trustees were discussing suing Bond for no other reason than to get him to hold a board meeting to talk about finances. A three-year Ernst & Ernst audit of the opera released in December of 1970 had said, “. . .we sought to reconcile certain transactions relating to the notes payable with the accounting records of the company but were unable to do so.” A special committee was appointed to investigate some $400,000 in bank loans to the Opera which were signed for or guaranteed by Bond.

On March 17, 1971, Bond finally held a meeting at the Dallas Country Club. The report of a special review committee cleared Bond and the Opera officers of misappropriating funds: “The Committee is of the opinion that these funds were used for the benefit of the Dallas Civic Opera Company.” However, the committee concluded that though loans had been spent by the Opera and obtained under the hand of Bond, they were not legal obligations of the Opera. That left Bond holding the sack.

Jim Bond wrote off any debt the Opera had to him and publicly took credit for it as a benefactor. But on at least one of these bank notes – $211,382 at Dallas International Bank – Bond never paid the bank. The loan was forgiven, according to bank records.

Like other close calls, the internal fiasco at the Opera was turned around and became a success story. Bond was in fact worth a lot of money to the Opera, but he left his curious brand; benefaction came from within a cloud of strained, confused circumstances that prompted infighting and counter-threats of lawsuits by Bond against his beloved Opera. He took what some insiders consider a graceful exit in 1971. On the outside (as well as among some insiders), Bond again came out the winner.

It is impossible to find the winner for one of the most spectacular fund-raising dinners in Dallas – but it is clear that Bond’s Opera came up the loser one night in May, 1969. The Fairmont Hotel had just opened and the Dallas Civic Opera filled the ballroom with nearly 1000 people who paid $150 per ticket. There was a full orchestra; there were ice sculptures; Robert Goulet sang; there were elephants rented from a farm in Oklahoma. It was truly an evening of high society. But when the bills were paid, the net gain from the banquet was $17.

“I had guaranteed [the Fairmont] $80,000 for that damn thing,” says Bond. “It was one hell of a party, and a big to-do. Hell, it got the society gals on the front page and it got the Civic Opera in the paper.

“I am the best party-giver in this city. Hell, I have ice carvings, orchestras, food – I put on one hell of a show!” He says he wasn’t in charge of the Fairmont party, but that he did get the elephants: “I got those damn things! Who the hell else has done that before?”

Not all Opera parties’ were alike, however. Bond, with an entourage of friends that included the late DCO Director Larry Kelly, once drove to the Naval Air Station in Grand Prairie and boarded a private jet owned by LTV. They flew to Las Vegas, where there were, Bond says, discussions of an exchange between the Dallas Civic Opera and the Las Vegas Symphony. “Are you kidding?” says one of those who went on the trip. “When we got there, everyone was given $200 worth of chips. We had a ball.”

Bond says he paid for the trip out of his own pocket.

After Bond stepped down as president of the Opera, there were attempts to remove his name completely from the Opera’s programs. His successor, William Hudson, argued that some unnamed city leaders would not support the Opera as long as Bond was involved.

Bond won’t admit he was run off from the Opera. “I could still be running that damn Opera,” he says. “I could squash those pipsqueaks. They give $100 and think they can run the damn thing.”

The Opera fiasco only added to the concerns even his best friends had about Bond. A. D. Martin Sr., the multimillionaire who recently participated in a takeover of Dallas International Bank, has known Bond for years. “He’s a dreamer and a charming man,” Martin said in an interview, but added, “he’s always been a bad businessman. He has no money sense: He’ll loan it all over, and I’m confident there are people who owe him. And loads of people have written off money to him.”

Martin is himself one of the people to whom Bond is in debt. Years ago, he lent Bond $141,000; he hasn’t collected a penny.

“He’ll never pay it and I’ll never ask him,” says Martin. “Sometimes, he’ll mention in a call, ’A. D., I’m gonna pay you back,’ but I know he won’t and I won’t ask him. I don’t know why.”

But Martin did refuse once to mix |friendship with business, when Bond had a $35,000 debt to Trinity National Bank. Martin, a controlling owner of the bank, knew that Bond had lent $50,000 to a Highland Park doctor years before without even taking a note on it. So aware of Bond’s financial unreliability was Martin that he engineered a way for both debts to be settled: He drew up a note for Bond and told him to take it to the doctor for signing. When the doctor paid up, it cancelled out Bond’s debt at the bank.

Bond did make money in business, but as in his charitable enterprises, his successes were rarely solo performances. When fortune was his, Jim Bond was in good company – Martin, Jim Ling, and Troy Post.

Bond met Post at the Linz Awards in 1959. Post then controlled the National Bank of Commerce and the Bank of Services and Trusts (later DIB). Post is said to have wanted Bond linked to his banks for his civic prominence; he later made Bond vice chairman of National Bank of Commerce, and chairman of the board of what would become Dallas International Bank. There was a complementary relationship between Post and Bond. Post likes to stay in the background and avoid hoopla; Bond is the master of front-running and loves fanfare. Post had the money and the business acumen – his Greatamerica Corporation, which controlled Braniff Airlines, sold for about $550 million – and Bond had the style. One former associate says Bond used to call himself Post’s “waterboy.”

Bond teamed up in similar fashion with A. D. Martin. Of their relationship, Bond says, “He’s quiet and rich as hell and I front-ran – I can cuss and I’m tough as a boot.” Together, Bond and Martin bought into LTV, Ling’s pyramiding dynasty. They were made board members. In 1970, they sold their stock to Ling and walked away with $2.5 million apiece.

Bond resents the implication that his wealth was derived from the expertise and management skills of other people, for whom he negotiated and did public relations. “A. D. made a lot of money off me on the LTV stock sale,” Bond says. “I’m not saying I could have done it myself, since 1 probably did it on his credit. But I organized a bank [DIB] for him.”

There were, in fact, business ventures in which Bond played a leading role. One of them was the construction of Manor House, the downtown apartment house atop DIB. To make the top 20 stories of a 24-story building an apartment tower separate from the bank and parking garage below it, Bond obtained “air rights” – normally reserved for instances in which a developer builds over a highway right-of-way or railroad. It was an exceedingly complex proposal, and Bond became the first man in the U.S. to divide a single building in two so that part of it could qualify for federal aid to housing. He was granted a $4.7-million mortgage guarantee from the Federal Housing Administration to construct the 242-unit complex. Four years later, the company that owned Manor House, lacking tenants, defaulted on the loan and the property was foreclosed by the government. It has since been sold and now is said to have a tenant waiting list. Says Bond, “Hell, I was just 10 years ahead of my time.”

It was only a matter of time before Bond’s private fortunes began to crater too. By 1971, he was $1 million in debt on everything from club memberships to repayment of a loan from his wife. He was sued by former business associates. The Fairmont Hotel, where Bond threw so many of his parties, took him to court and won a judgment for nearly $15,000 in unpaid bills. Brennan’s sued and got a judgement. Linz Brothers sued.

It was a tumultuous time tor the old man, keeping up the lifestyle of an aristocrat when he had no assets and no cash. He didn’t even have access to Mrs. Bond’s holdings; her estate had been completely severed from his “so nobody would think I’m a gigolo,” he says.

When a rich man goes poor, the most critical loss is his self-esteem. Bond still drove a big car, still tipped waiters $50 at the Dallas Country Club, still would pick up a friend in a limousine, still would appear around town dressed in pinstripes, a bold silk tie, and heavy gold cufflinks. Ironically, Jim Bond would find protection in his debts: Nothing of value was in his name – not the car, not his fashionable home on Wateka, not a single article of recordable value by deed, record, or title. Today, Jim Bond does not have his own banking or checking account. His monthly pension and Social Security checks are immune from attachment.

I asked A. D. Martin Sr., who said he considers himself Bond’s best friend and whom Bond estimates to be worth $78 million, whether he’d do any business of any kind with Jim Bond. He smiled broadly and nervously repositioned himself in his chair. “Boy, now you’re really. . . asking. . . .” He declined to answer the question fully.

“I never looked upon Bond as a businessman at all, but rather a man of civic affairs,” says a former business associate of Bond’s, who would only speak on a confidential basis. “Fred Lange rubbed off on Bond: He’s got the ability to excite others that way. James Bond is not a crook. He is just such a salesman that he sells himself into a dream and into a corner.”

Former Dallas School Superintendent Nolan Estes first talked about building a high rise educational complex downtown years ago. The school board considered it at arm’s length. It seemed like a good idea, but there were some nagging questions. How could the school district, which owns land downtown at the site of the old Crozier Technical High School, get involved with private enterprise?

Estes’ concept was a daring one: Engage developers to construct a combination hotel and office center on property owned by the school district, with space to be provided for school district administration offices and a magnet high school. Not only would publicly owned property begin to produce tax revenue, but massive tax savings would be realized from the space provided the school system. Estes also liked the idea of school kids and school buses downtown; he firmly believed that DISD presence in the business center would ensure business support for the school system. For seven years before his departure in 1978, Estes tested the political waters. An architect’s rendering was hung in the board’s conference room. But always, the school trustees brushed the plan aside.

Three years before he left the school district, Estes had another idea. He argued that the 1970’s and 1980’s would be a time of increased experimentation in the schools, a time of exceptional needs for the students as well as a time of an increasing tax burden as the city grew. A private, non-profit foundation could serve a district well by seeking money from private sources. He talked about the estimated $20 million that leaves Dallas every year for colleges and private schools outside Texas. If only the DISD had a separate office that could solicit and responsibly manage a big fund-raising program, donors would start changing their habits. The tax write-off would be the same, and the money spent on the kids would determine the quality of life in Dallas. The foundation would be legally separate from the DISD, but it would exist for one reason only – to give money for projects that the school board would probably not fund.

Dallas would be the first city in the United States to do anything like it.

It was one of those Estes innovations that grabbed people, and the school board went for it. Estes told the school board members that in the first year of operation, a foundation could capture $4 million in contributions.

In the fall of 1976, Estes received a letter of introduction from a man who’d seen philanthropy grow in Dallas, but more important, who himself had helped make it grow. It was from the man who had masterminded the construction of LTV Tower, who’d built Manor House, and who’d had vast experience in large-scale construction.

Estes met with James Bond at the school administration offices on Ross Avenue, then brought him in to see Rogers Barton, the DISD administrator responsible for foundation activities. “I think we’ve got our man,” Estes said when he introduced Bond. In March of 1977, the Foundation for Quality Education Inc. opened for business, with Bond as its president and chief executive officer. For Bond, it meant re-entry into civic life and his first managerial job since his HEW years. For the DISD, it was a coup to obtain – for free – the services of a man with the reputation of Bond.

Bond has been in business for the school district for two years now. During that time, he has argued forcefully that his foundation’s strategy has changed: Instead of placing first priority on soliciting funds, the foundation is marketing learning materials developed by DISD experts. And, of course, it has spent months and months developing detailed plans for the $113-million hotel, office, and school administration complex to be known as Eastern Gateway.

As was the case with the United Fund and with the Opera, Bond’s role has at times been bigger than his job. While his foundation is legally separate from the school district, Bond has formed curious relationships with school administrators and made curious appearances when school, not foundation, business was being conducted.

Since Bond has been linked to the DISD, a construction firm owned by a close personal friend of his has grown exponentially, from a small home renovator into a million-dollar firm with nearly 100 employees. The William Maxwell Construction Company is owned by William Oswalt III, who was number one consultant on a Las Vegas shopping center built by Bond, and Bond’s consultant on LTV Tower and Manor House. Oswalt’s fledgling firm, which reported a net worth of $19,500 in January of 1977, had not done any DISD work before the formation of the Foundation for Quality Education, but in mid-1977 was awarded millions of dollars’ worth of DISD construction work. Bond, inexplicably, had signed out bid specifications from the DISD construction office to review plans for those jobs Maxwell later was awarded. To date, Maxwell has been awarded more than $14 million in DISD construction work. And when Bond announced the foundation’s plans for Eastern Gateway, the William Maxwell Construction Company was named construction manager.

Bond denies any financial interest in his friend’s company, but Weldon Wells, the DISD administrator in charge of the school construction program, says Maxwell got its first jobs with the DISD on the recommendation of Jim Bond. Maxwell was deemed qualified by school administrators to do the work, Wells said. Wells’ son is an employee of the William Maxwell Company.

Friends may just be friends, and that is what Jim Bond says about the staffing of his foundation. The key people are those on the DISD payroll who were hand-picked by Estes after a period of time he once described to me as the foundation’s “wobbly start.”

But some on the foundation’s payroll are Bond’s longtime associates. Building manager for the foundation is Dianne Bumpass, a former clerical aide of Bond’s dating back to the Manor House days. Her brother Kenny, perhaps coincidental-ly, is on the payroll of the William Maxwell Company. Joe Abbey, a lawyer who once represented Dallas International Bank when it tried to collect from Bond on an overdue $21,000 loan, is Bond’s personal lawyer (Abbey was a key player in the recent DIB takeover by Bond’s buddy, A. D. Martin, and rancher Rex Cauble). Abbey serves as the foundation’s counsel and has the title of Assistant Secretary. Bond’s personal accountant, Tom Parish, is the CPA who recently completed long-awaited and unrevealing financial reports of the foundation. Parish was also associated with the Opera. And Gus Bowman, a former president of Dallas International Bank and of Exchange Bank and Trust, is a recent addition to the Foundation’s board of trustees.

Now there is Eastern Gateway. Bond says Supt. Linus Wright has come around to the idea – if Bond can get the support of the business establishment. Bond is now conducting a series of 25 meetings to get the project moving.

He is off again and running; a little controversy only spurs him on all the more.

He is that way in our interview. “It isn’t the storm at sea, it’s whether the ship comes into port,” he says. “And this one’s coming into port.”

Has Jim Bond ever lost a battle with words?

“No. No, dammit. I can out-talk ’em. Besides, I’m right.”

I asked Bond’s friend A. D. Martin Sr. if he thought Bond’s work at the Foundation was an attempt by Bond to get back in the limelight, to do some front-running. He grinned. Then I asked him if he thought Eastern Gateway was a totaHy unrealistic proposal. “Of course it’s a joke!” he said, laughing.

A veteran of philanthropy in Dallas leans back in his chair when asked about Bond’s plans for Eastern Gateway. “When Bond started up with the DISD, people hadn’t seen him for years. He’s trying the same thing he always did, but he’s lost the confidence of the business community.”

Does Jim Bond think he has the confidence of the city’s business community?

“I’ve sure got somebody fooled if I don’t,” he says, tapping his right hand on his right shoulder. “That would be me.”

Related Articles

Hockey

What We Saw, What It Felt Like: Stars-Golden Knights, Game 1

Deja vu all over again. Kind of.

By Sean Shapiro and David Castillo

Movies

A Rollicking DIFF Preview With James Faust

With more than 140 films to talk about, of course this podcast started with talk about cats and bad backs and Texas Tech.

By Matt Goodman

Business

New CEOs Appointed at Texas Women’s Foundation and Dallas Area Habitat for Humanity

Plus: Former OpTic Gaming CEO Adam Rymer finds new e-sports post, Lynn Pinker Hurst & Schwegmann hires former Mary Kay chief legal officer, and more.

By Celie Price and Layten Praytor