Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

This day in the mid-’30s was a fairly typical one for the staff of the Dallas Dispatch:

On Akard Street, by the newspaper’s offices, a married columnist was being chased by his girlfriend, who had caught him with some of his fellow newsmen in a whorehouse across from the Dispatch building. (The Fidelity Union parking garage stands on the site today.) Their race down Akard was observed and commented on by journalists leaning from the composing room windows on one side of the street, and by ladies leaning from bordello windows on the other side.

Meanwhile, back in the city room, a wealthy businessman was threatening to mar the handsome face of city editor Clarke Newlon because the paper had run his son’s name in a story about a bookie joint bust. Cliff Blackmon, the stereotype foreman, was summoned. Wielding a 40-pound “pig” of lead, Blackmon, who doubled in brass (or lead) as city room bodyguard, chased the irate father down the stairs.

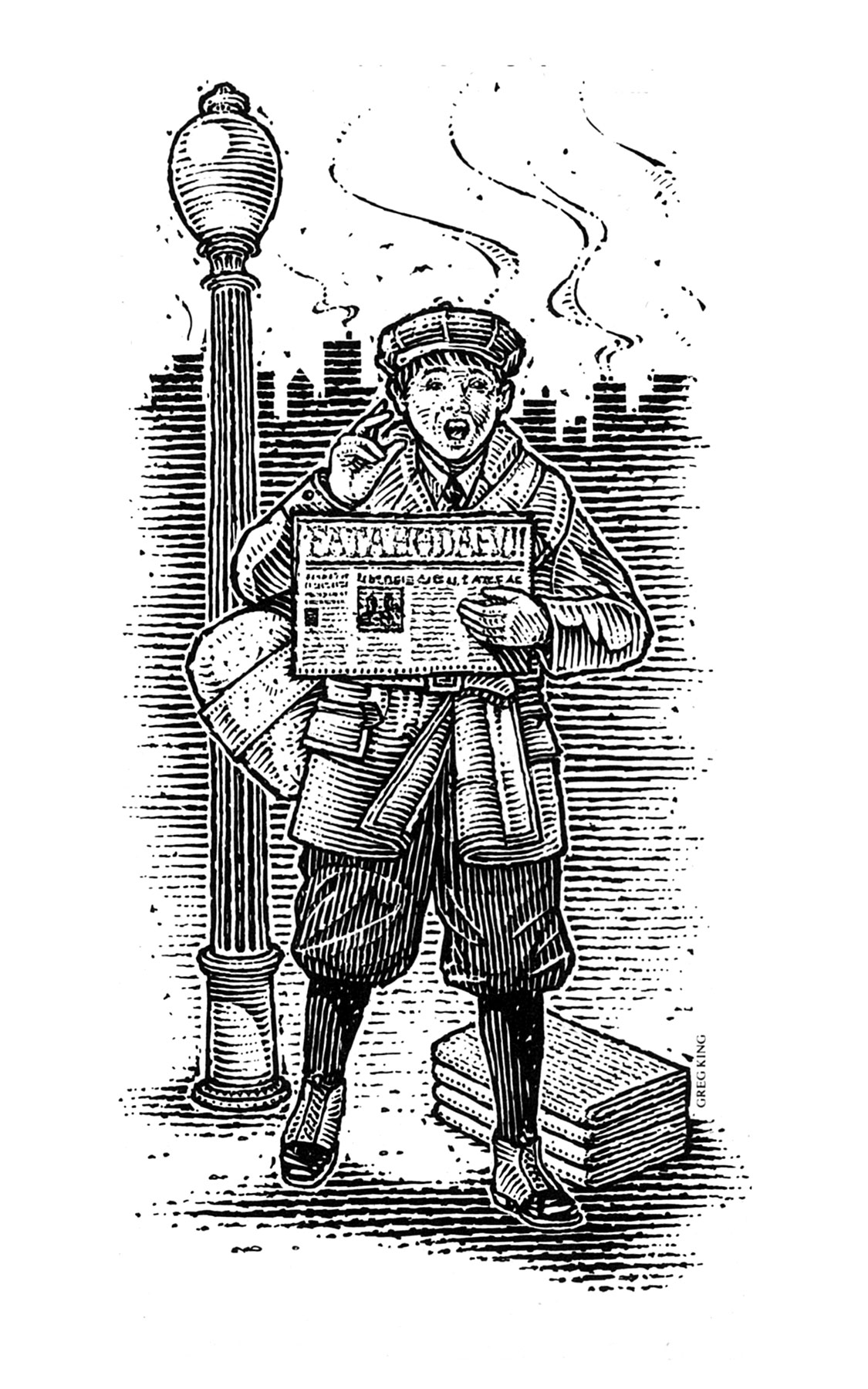

This break in routine didn’t distract Newlon from putting together an “Extra” with a banner announcing that Bruno Richard Hauptmann had been found guilty of kidnapping the Lindbergh baby. An army of ragged newsboys appeared from nowhere and began hawking the papers.

One of the newsboys ran to his appointed post outside the offices of the Dallas Times Herald, where trucks were being loaded with papers whose headlines proclaimed that the jury had found Hauptmann innocent. A thunderstruck Herald editor grabbed a Dispatch and rushed to check with Associated Press, their source on the verdict in the Lindbergh trial. He discovered that an AP man stationed in the courtroom window had fouled up the pre-arranged signals to his confederate on the ground. The Dispatch’s version, which had been phoned to them by someone at the scene, was correct.

The next day, page one of the Dispatch featured a six-column photograph of the Herald’s front page. Beneath it in bold type was a line reading “We’d Rather Be Right Than Be The Times Herald.” The taunt was composed by the Dispatch’s young assistant city editor, James F. Chambers Jr.

Today, Chambers is chairman of the board of the Dallas Times Herald.

According to the legend, bareknuckle journalism began in Dallas one day in 1906 when a tall, stately Englishman, Alfred O. Andersson, stopped to study a cigar display in the window of a drugstore at Main and Ervay. Andersson smiled, gave his mustache a twirl, and said to himself, “This is it. A city where men can afford such expensive cigars will support another newspaper.”

Andersson had been sent out by E.W. Scripps, the Ohio newspaper entrepreneur, to pick the most likely spot for an afternoon paper in the Southwest. When he chose Dallas, Andersson, a former Kansas City newspaperman and war correspondent during the Spanish-American War, was named publisher, a role he retained for 32 years at the Dispatch.

The Dispatch was part of the Scripps-McRae Press Association, which in 1907 became United Press, whose wire services the Dallas paper used throughout its lifespan. Later the Dispatch moved under other Scripps umbrellas—Scripps-Canfield and the Scripps League—though never into the vast and better-known Scripps-Howard chain. It also received cartoons, features, and serialized adventure and love stories—forerunners of soap opera—from Scripps’ Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA).

Andersson launched his newspaper in September 1906, when the “Dallas Fair” was in progress. The first issue was, in fact, just a thousand copies, published in Kansas City and brought to Dallas by Andersson in a suitcase and trunk while the second issue was being edited in a small office at 319 Commerce. Number 1, dated Monday, September 17, 1906, was a broadsheet of four pages with only national news and no advertisements. Like hundreds to follow, it was a penny a copy. The second issue contained a story about the fair’s efforts to bring William Jennings Bryan to the exposition. The year before, the fair’s celebrities had been President Theodore Roosevelt and auto racer Barney Oldfield.

In 1906 Dallas was a town of 110,000. Virtually its only claim to distinction was that it was the country’s leading saddle-maker. In its second week, the Dispatch announced that an Indiana firm would build a factory in Dallas to manufacture men’s long underwear. The same edition carried an advertisement for Freckle-buster, a miracle face lotion manufactured by the Frecklebuster Company of Dallas.

There were already two newspapers in Dallas, the Times Herald, which had been founded in 1879, and the Dallas Morning News, which assumed that name in 1885 but traces its roots back to the much older Dallas Herald. (The News introduced a fourth paper, the Dallas Journal, in 1914.) From the beginning, Alfred Andersson aimed the Dispatch at what would now be called a “blue collar” readership.

The Dispatch often took swipes at public utilities, urging stricter rate controls. It fought increases in streetcar fares and exposed lax enforcement of pure milk and food laws. In the days before electrical home refrigeration, it supported the Dallas Council of Mothers in their fight against the escalating price of ice. Features about rat infestation in groceries, warehouses, restaurants, and homes brought about a three-year city program to wipe it out. In the ’20s, the Dispatch took on the Ku Klux Klan. Editor-in-chief Lewis Bailey was threatened by Ku Kluxers but refused to budge when they ordered him off a streetcar. Klansmen came to his house, but he slammed the door in their faces. Telephone and mail threats from the KKK were daily occurrences at the Dispatch offices.

The Dallas of the Dispatch’s heyday, the mid-’20s to late ’30s, was a rough, colorful town. Prohibition seemed to make forbidden pleasures all the more pleasurable. Bootleg liquor flowed freely, and gambling and prostitution were all but uncontrolled. (Akard Street, across from the Dispatch offices at Federal and Bullington, was the site of half a dozen bordellos.) Policemen and sheriff’s deputies were for the most part lenient. Their way of handling habitual criminals they couldn’t quite get the goods on was to take them to remote Bois D’Arc Island in the Trinity River and work them over.

The Dispatch kept an eye on the cops, too. The paper took on one police chief notorious for goofing off and gave its readers a daily report on his presence or absence from his office. City Hall reporter Vern Torrance needled ward-heeling city commissioners and had special fun with Mayor J. Worthington (“Waddy”) Tate, a good-old-boy populist from Oak Cliff elected by fluke in 1929. Among Tate’s few accomplishments as mayor was the removal of the spikes from the ledge around the municipal building so “the people” could sit there. Tate’s incompetence as mayor is often cited as the reason for Dallas’ adopting the council-manager form of government. The Dispatch’s exposure of corruption and incompetence in the commissioner system contributed significantly to this reform.

The newspaper was ruled from the second-floor office of Alfred Andersson, whose shabby cubicle opened onto a long, narrow newsroom. Andersson was a genteel, teetotaling man, as was Lewis Bailey, his editor-in-chief. A sedate man who was usually seen puffing reflectively on his pipe, Bailey’s composure was shaken only rarely, and most often by people who honked their horns while Bailey was writing his editorials. He would fling open a window to shout angrily at the offender.

At the opposite end of the room from Andersson and Bailey were two men who took turns over the years in the city editor’s chair.

Ira Welborn, who came to the paper from the Cleveland Press, was a wiry, dark man feared by reporters for his short-fused temper and for vendettas ignited by personal dislikes. But Welborn was a tough reporter, a ruthless digger for details, who expected his reporters to be as relentless as he. One particular object of Welborn’s ire was the Veterans Administration; a veteran of World War I, Welborn directed editorial crusades against incompetence and greed in the VA.

Because of his bouts with the bottle, Welborn was twice replaced as city editor by Clarke Newlon. Newlon himself was in and out of the Dispatch over the course of several years. He left once to work at the Chicago Times, where he covered the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and the Black Friday stock market crash of 1929. He returned to the Dispatch, left again to be managing editor of NEA, but returned to the Dispatch once more.

In Newlon’s opinion, Welborn was the world’s greatest newspaperman, and Newlon often acted as Welborn’s protector. When the stern and strait-laced Andersson or Bailey would start toward Welborn’s end of the newsroom, Newlon would jump from his desk to run interference long enough for Welborn to hide his bottle and pop a few breath mints.

Welborn’s tenacity, Newlon says, was his great strength as a reporter—that and a streak of recklessness. When he was with the Cleveland Press, Welborn once got a story out of an FBI agent by challenging him to a marksmanship contest. Each bull’s-eye won Welborn another bit of inside information; eventually, he outgunned the G-man for the whole story.

“When Ira was drunk,” Newlon says, “he liked to wander up and down Main Street, and whenever we passed a policeman he would step on the cop’s toes. Cops didn’t appreciate this and would tell me to get Welborn away fast, before he was busted in the mouth with a nightstick. But when Ira didn’t want to do something, he would simply wrap his arms around a lamppost and cling. He wasn’t a big man, but this made quite a scene on a crowded downtown Dallas street.”

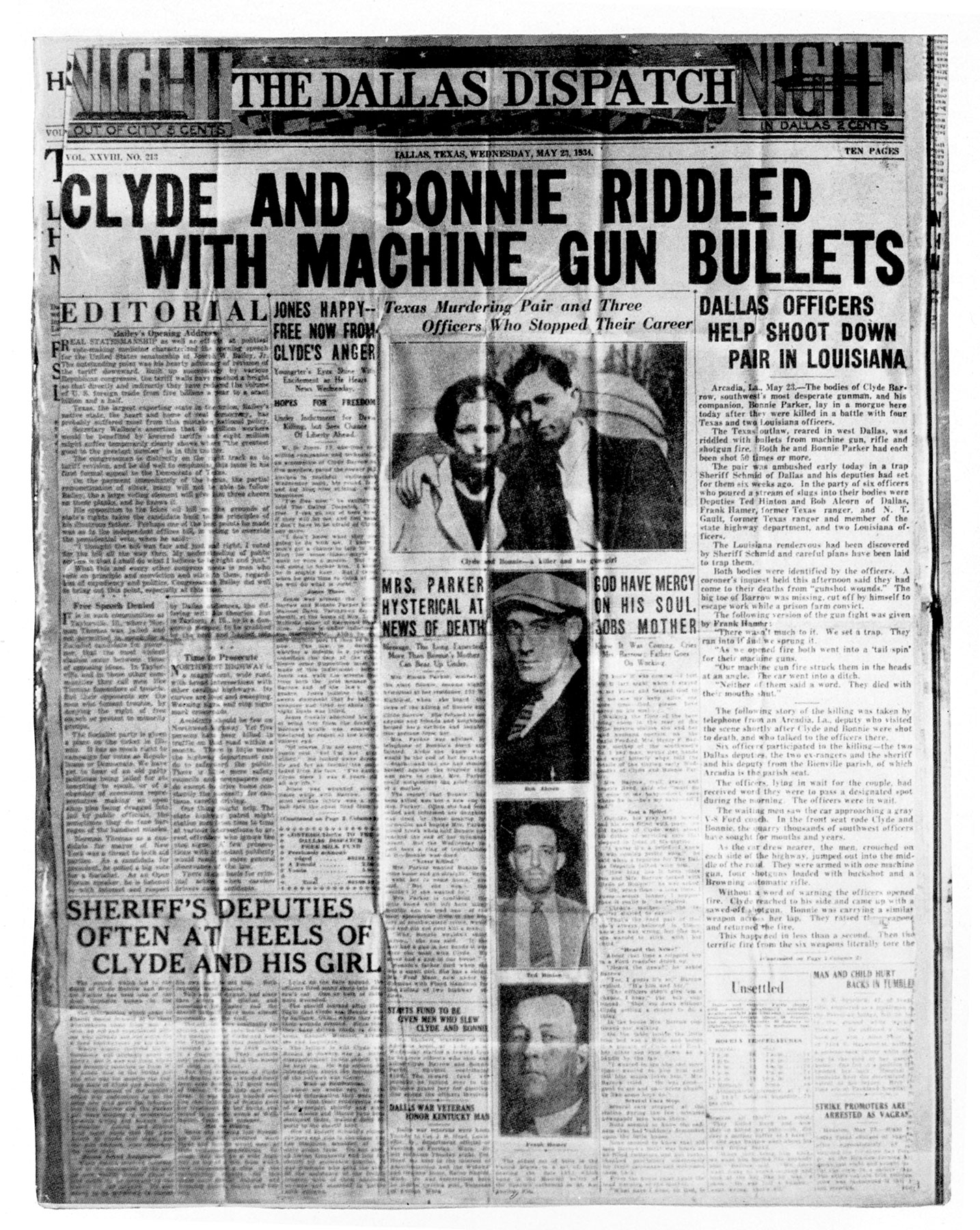

Newlon himself was involved in chasing down big stories. Perhaps the biggest of all in the heyday of the Dispatch was the pursuit of Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. Newlon and sports editor L.D. (Red) Webster teamed up to check out a tip from one of the Dispatch’s private circle of underworld informants that Bonnie and Clyde were hiding out in the Trinity River bottoms. Webster, now a vice president of Lone Star Steel, recalls, “Newlon and I just missed them by a hair in the river bottoms and again in the country near Garland. We gave up waiting by a bridge about two hours before they were seen driving out of the woods at that spot.” And what would they have done if they had met up with Bonnie and Clyde? “Well,” Webster says, “if they’d have stood still long enough and not shot us, it would’ve made a helluva story.”

Webster credits Newlon with Bonnie Parker’s reputation as a cigar smoker. “A picture of Bonnie holding a six shooter was found in a motel where she and Clyde had holed up. We got a print and, after studying it for a minute, Newlon said she looked like she needed a cigar in her mouth. An artist painted the stogie in and the retouched picture ran on every Page 1 in the country. After that, she was known all over as a cigar-smoking gun moll.”

One of the first reporters on the scene after Bonnie and Clyde were killed in ambush near Gibsland, Louisiana, in 1934, was the Dispatch’s Pat Kleinman, now chairman of the board of American Graphics Press in Dallas. “I never had much status with my kids,” Kleinman says, “until they and their friends went to see the Bonnie and Clyde movie several years ago and spotted my by-line on a Page 1 Dispatch story about the ambush, blown up as a poster display in the theater lobby.”

Pursuing a story in the gangster era of the ’30s led to all sorts of accommodations with both cops and robbers. Red Webster once responded to a telephone tip that the kidnappers of Oklahoma millionaire Charles Urschel had been rounded up by the FBI. At the FBI office, he found that the G-men were about to spring a trap in Memphis for Machine Gun Kelly. Fearing that publicity about the Urschel case would spook Kelly, FBI agent Frank Blake told Webster that if he would sit on the story until Kelly was rounded up, he could have the Urschel kidnap story as an exclusive. J. Edgar Hoover confirmed the promise in a phone call to Dispatch publisher Andersson.

At an agreed-upon time, Webster returned to FBI offices. Blake’s secretary, Lorene Tomlinson, told Webster that she had to leave her desk for a few minutes and certainly hoped nothing would happen to the large brown envelope on her desk. Taking the hint, Webster grabbed the envelope and rushed to the Dispatch, where he found it contained full criminal dossiers and photographs of the kidnappers. The Dispatch scooped the nation, and most exquisitely the News and the Herald.

Clarke Newlon, who now lives in Washington, D.C, recalls that “one of the best sources was a guy named Walter, whose father was a sure enough bank robber. Walter kept pretty clean. He did serve as a clearing house for visiting talent looking for a good dishonest opportunity, and he occasionally fenced a little counterfeit. Walter kept up with everyone and everything on the wrong side of the law.

“One morning, our police reporter heard that a man whose head had been blown off by a shotgun had been found in a car between Dallas and Fairfield. The police couldn’t identify him. I called Walter, who said he’d phone me back in a couple of minutes. He did, gave me the man’s name, and explained he was new in these parts, had tried to hijack a load of liquor but didn’t have any luck. We carried the story with the victim’s name. In 30 minutes, half the police and sheriff’s departments were in the newsroom asking questions. We didn’t talk, of course; the law wasn’t very insistent in those days.”

I got my start at the Dispatch because my brother Frank had preceded me. Like most Dispatch staffers, Frank has his Bonnie and Clyde story. Frank was sent out to interview Clyde Barrow’s parents early in their son’s career as a gunman. During the course of the interview, Pa Barrow asked his wife if she’d been taking food to Clyde in his Trinity River bottoms hangout. “I sure have,” she said. “The boy’s got to eat.”

“Ma, if you don’t stop that,” Barrow replied, “you’re going to get your ass shot off.”

Frank had the less risky duty of amusements editor for a while. He distinguished himself in the job by two reviews. One was of a young performer named Ginger Rogers; Frank said she was a clumsy turkey who’d never make it in show business. The other was a rave review of a painting exhibited by photographer Bill Langley, who said he’d bought it from an exciting new artist in Paris. When other critics, alerted by Frank’s review, asked to see the painting, Langley confessed it was a piece of cardboard he’d left in the bottom of his parrot’s cage for a week, dried in the sun, varnished, matted, and framed.

Like other Dispatch reporters, Frank also wandered into Ira Welborn’s line of fire occasionally. One morning, he came to work to find that the stacks of news releases and photos he’d sorted on his desk the day before had been dumped in a trash can by Welborn, a stickler for tidiness in everyone else. On the top of the heap was Frank’s typewriter. The usually mild-mannered Frank threw a hunk of lead at Welborn, who ran him into the street. Clarke Newlon, a close friend of Frank’s, managed to arbitrate.

Newlon, at Frank’s urging, gave me my first newsroom job at the Dispatch—summer work as a copy boy with no pay. My assignment was to arrive early in the morning before the staff, fill bowls on each desk with wallpaper paste used to stick pages of copy together, clip local stories from the News and have them in a neat stack on the city desk by the time Newlon arrived. I also served as a runner to summon reporters or editors from the houses of pleasure across the street whenever a hot story broke.

When I graduated from high school, Newlon helped get me a scholarship to SMU. In return, I covered campus news for the Dispatch.

Working the police beat during summer vacation, I was sent to report a drowning and decided to go for the Pulitzer Prize. My piece began, “Snarling King Neptune rose from his foamy lair at White Rock Lake today to claim Dallas’ sixth drowning victim of the year.” Newlon rushed this immortal paragraph back to me in the police pressroom by Western Union delivery boy. In the margin, in words that broke my heart, he had scrawled, “Forget drowning. Shag ass back to White Rock. Interview Neptune and get pictures.”

Cubs aged fast at the Dispatch. Newlon consigned me to the tiny dungeon that was the police pressroom in City Hall with three veterans who knew all the tricks: Ken Hand of the News, Bill Duncan of the Herald, and the legendary Jack Proctor, then doing a stretch at the Dallas Journal.

Proctor, who has already been immortalized in this magazine by Blackie Sherrod (October 1975), polished off several half-pints of Town Tavern rye daily. He chased them by biting holes in oranges and squirting the juice in his mouth. He said this kept him from getting rickets. He once stole an engraved, pearl-handled automatic pistol that had been given to the chief of police by the boys on the force. When he was seen sporting it in his belt at a wrestling match, it took three cops to get it away from him.

I was aware that Proctor was a formidable reporter. Before I was assigned to cover the police beat, I had heard that Proctor was pulling off incredible scoops on a notorious gang of Dallas hoods. The reason became apparent when Proctor was arrested driving their getaway car.

Bill Duncan was at the end of his career. One afternoon I rode with the city ambulance driver to answer a call to the Tex-Herald Cafe across from the Herald offices, where we found Bill near death in a booth. He had drunk poison mixed with beer. He died before the ambulance could reach Parkland.

Ambulance riding was at first a great thrill, and the driver would allow me to take friends along on the wild rides, careening out to answer calls. One of the friends, who shouted and waved at startled pedestrians through the broken back window, was Waller Collie, later president of the Dallas Bar Association. But by the time I was 21, I had seen enough gore to last a lifetime, and today I detour swiftly when I catch sight of an auto accident or an ambulance.

One of the most painful of my experiences as a reporter happened in the spring of 1941. Eddie Barr, the Dispatch’s amusements editor, had become the city’s best-loved and most-read columnist. His daily “Rialto Ramblings” was an entertaining mixture of gossip and showbiz trivia. His hangout was Antonio (Pop) DaMommio’s spaghetti house on Bryan. Pop treated Eddie like a son. As a cub reporter, I revered Eddie.

On the evening of April 12, 1941, Eddie was at Pop’s. His wife, Juanita, who was also Jack Proctor’s sister-in-law, was paying a visit to the Swiss Avenue apartment of an attractive young girl named Blanche Woodall.

I was on the ambulance-riding beat when the call came in that Blanche Woodall had been shot. Riding to the scene, the driver informed me that Blanche was Eddie Barr’s mistress. When the police arrived, Lieutenant “Pokey” Wright phoned Pop’s and asked for Eddie. “Eddie,” I heard him say, “Nita has killed Blanche.” There was silence a moment, and when Pokey hung up he said, “Nita just went by Pop’s, threw the pistol on Eddie’s table, and told him what she’d done.”

Juanita’s trial was, of course, a sideshow. Spectators brought lunches and ate them while Juanita’s lawyers, Maury Hughes and Ted Monroe, Dallas’ early versions of Racehorse Haynes and Percy Foreman, played to the grandstand. Their defense was based on the premise that she had acted in a fit of uncontrollable, but understandable, rage at the woman who was breaking up her home.

According to Blanche’s maid, Nita came unannounced to Blanche’s apartment; the two women talked quietly and telephoned a liquor store for a bottle of whiskey. They decided to go out, and Blanche changed clothes and put on her make-up, then began helping Nita put on her make-up. While the cosmetic touch-up was in progress, Nita took the pistol from her purse and shot Blanche twice in the face.

On March 5, 1942, Juanita Barr was sentenced to a term of four years for murder without malice. She was freed on an appeal bond on March 11. The court of criminal appeals upheld the conviction, but an appellate court ruled for a new trial, which for some reason was never held. Eddie quit the Dispatch and moved to Houston, where, for a while, he managed a restaurant. Though he and Juanita were divorced, most who knew them think Eddie used the influence he had gained as one of Dallas’ most popular men about town to keep her from prison. He died in San Antonio in the late ’40s; Juanita’s fate is unknown.

Eddie and Juanita Barr’s troubles profoundly affected the Dispatch staff because he was so much a part of the family the hard-working, hard-drinking, and poorly paid staff had become. Socializing at places like Pop DaMommio’s was one of the pleasures of working for the Dispatch. Bonnie Langley, who was first married to sports reporter John Binford, tells how Pop ordered her to feed her baby buttered spaghetti to make him grow up strong, and once offered to provide a feast on Christmas Eve if she and John would first attend midnight mass at Sacred Heart Cathedral. It was SRO at the cathedral, so John, who had had more than a few drinks before going to church, went outside, removed his hat, and fell asleep on the front steps. When Bonnie came out after the services, John was snoring soundly; in his hat was $1.80, dropped there by late arrivals. John’s only comment was that he’d never made that much in an hour’s work at the Dispatch and that henceforth he’d include Sacred Heart in his regular rounds.

There was one exception to the camaraderie of Dispatch staffers: the advertising people. All newsroom neophytes were indoctrinated with the tenet that ad men came from beneath wet, flat rocks and that their only mission was to adulterate the newspaper with puffery for their clients. Eddie Barr and Jack Patton once enhanced their stature in the newsroom by using a hatchet to chop their way to a fifth of bourbon they had heard was secreted in Sig Badt’s desk in the advertising department. When Badt protested, Patton’s reply was, “You bastard, why in the world would you lock it up? Don’t you trust us?”

When Clarke Newlon threw the ad manager out of the newsroom for protesting a feature exposing sellers of unsafe used automobile tires, publisher Andersson danced jubilantly from his cubicle shouting, “Great! Great!” He did a similar jig after the ad manager, backed up by several city fathers, appeared in the newsroom to protest the paper’s attacks on horseracing at the State Fair, and was firmly ushered out.

Ad department alumni did all right for themselves despite their second-class citizenship at the Dispatch. Sig Badt went on to become a well-to-do insurance executive. Laurence Melton acquired a printing firm and became head of the Citizens Charter Association. Leo Corrigan Sr. amassed multimillion-dollar real estate holdings.

Teetotalers Andersson and Bailey found their tolerance stretched to extremes by some of their staff. Costly run-ins with the jug led them to can sports editor George White, who became a nationally recognized figure in sports reporting when he moved on to the News. Ben Hill, a sports writer who billed himself as “The Great,” had trouble keeping his head screwed on straight and finally lost his job when cops raiding a bookie joint found Hill manning the telephones.

Bob Campbell, a brilliant writer, used a whiskey bottle as a paperweight when he acted as weekend city editor while his bosses were on the golf course. When he went into the army in World War II, Campbell was assigned to exercise the general’s horse at Camp Wolters. Campbell kept a fifth of bourbon hidden in a bush on the base. When he dismounted to retrieve it one time, the horse nipped him on the rear end. Campbell took a swig, re-hid the bottle, and bit the horse back. An officer who witnessed the incident marched him off to the guard house for being drunk and disorderly. He was, in fact, just being Bob Campbell.

Photographers, then as now, marched to a different drummer. Jimmy Valentine once held a .45 automatic in one hand and his bulky Speed Graphic in the other to hold off airline personnel trying to keep him from the scene of a crash at Love Field. Tommy Kane, who relished his naps in the darkroom, rigged up a device that exploded an entire case of flashbulbs if anyone opened the door without permission.

Wilbur Shaw, the telegraph editor, held the record for alcohol consumption on a staff where booze was drunk the way most offices consume coffee. Clarke Newlon says Shaw’s was “not just ordinary capacity, like a quart a day. It was Prohibition and the Depression in Dallas when Wilbur was there. Ice-cold gin was a dollar a pint, delivered. Wilbur would, cross my heart, order, get, and drink as many as 10 pints in a morning. Most of the time, but not always, he continued to function.”

There were well-behaved members of the Dispatch staff, too. And for the most part they coexisted with the wilder sort. Bill Payne, who in his retirement restores old books in Dallas, was a conservative editor with an eye for detail. He went on to become amusements editor of the Dallas News later in his career. Payne once reluctantly joined Jack Proctor and a cop on a police motorcycle racing through traffic to cover an explosion. “It was like riding on a bronc behind W.C. Fields and the Lone Ranger,” Payne says.

Other well-behaved Dispatchers who went on to success elsewhere were Terry Walsh, now managing editor of the Dallas News, and his brother Mason Walsh, publisher of the Arizona Republic and the Phoenix Gazette; Frank Chappell, PR man for the American Medical Association; Frank Langston, business news editor of the Times Herald; Joe Murray, advertising agency owner; Hal Lewis and Bert Holmes, who rose to executive editorial positions at the Herald; and Elgin Crull, who for many years was Dallas city manager.

Certainly one of the bravest newsmen at the Dispatch was Jack Parks, who made a deal with the newspaper and with NEA to ride his Harley-Davidson along the route of the then-proposed Pan American Highway through Mexico and Central America, sending back features about his adventures. Several stories appeared before Jack, bruised from spills and weakened by illness, died of a jungle fever. He was buried somewhere down there by the natives.

With a few exceptions, in those days women were relegated to fashion, wedding, and party writing. Even Ira Welborn petted and pampered them, and sedate Lewis Bailey was often seen giving fatherly hugs to Marihelen McDuff, who went on to be PR director for Neiman-Marcus in its most glamorous years. Many of the Dispatch’s society writers were from prominent Dallas families: Mamie Folsom Wynne, Patsy Burgher, Allena Duff James, Patsy Field Edwards, and Garland Mac Chapman, who married Charles Cullum and whose daughter is Channel 13’s Lee Clark. Rose Marilyn Frank and Mabel Duke became forces in public relations firms in Dallas. Ruby Clayton McKee was for a long-time society editor of the News.

A few of the Dispatch’s women reporters fit the career-girl image created by Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday. Ticky Poyner was a small, pretty blonde who petrified strangers with her command of oilfield cusswords. She moved to New Jersey to publish a thriving weekly newspaper. Vera Addington, who was one of my mentors, was a Reporter’s Reporter who competed successfully with men on every important beat in the city. She was first married to photographer Bill Langley, then to another photographer, Lawrence Joseph, until her death.

The Dispatch newsroom we worked in was a sweatbox with a rusty decorative tin ceiling that leaked during rains and rattled when the presses were running or the antique fans were turning. On winter mornings when the porter was late as usual in firing the furnace, the staff worked in topcoats and lit fires in wastebaskets.

There was a unique affinity between the newsroom staff and that of the composing and press rooms, a bond which was reinforced by the shopmen’s skill in making home brew. Earl Moore, the foreman of the composing room, was the master brewer; four bottles of the stuff would fell any Dispatcher except Wilbur Shaw, who could talk coherently even after a half-dozen Earl Moore specials topped off with a quart of brandy.

The chief makeup man was “Judge” Middlebrook, who had a law degree but claimed that he could make more money in the shops. Judge also made homebrew, and had a passion for garlic—raw and in bunches. When the brew was working nicely, Judge would stop on his way home, buy a handful of garlic, a loaf of bread, and a half pound of butter. Sitting on his kitchen floor by the beer jar, he would drink from the still-working batch through a straw while munching garlic cloves and buttered bread.

When Judge came to work after a bout with his garlic-chased brew, the makeup editor would use a yardstick to indicate to him where various stories should go on the page. The area close to Judge was untenable.

Ernie White, who ran a linotype machine and was in charge of handing out copy to the other operators, acted as a self-appointed editor, cleaning up The Great Ben Hill’s often-blue sports column and suggesting that Wilbur Shaw be sent home when his copy became illegible. On the other hand, it was always suspected that typesetters and proofreaders occasionally tinkered with stories to brighten bad days or punish reporters on their hit lists.

One extra on the suicide of a prominent citizen began with the information that the “well-known Dallas financial figure shot himself to death today in the bathroom of his Highland Park home.” But when it appeared in print, an “i” had replaced the “o” in the word “shot.” No one ever convinced the editor this was an accident. Another time, an ad for a movie called Fool for Luck appeared with an “F” in place of the “L” in the last word. This hurt only the advertising department, so the newsroom sent the shop congratulations.

Everyone at the Dispatch stood in awe of George Hoehn, the pressroom foreman described by Terry Walsh as “an ink-stained wretch who kept our junky presses rolling with baling wire, assorted odds and ends, and a large supply of Yankee ingenuity. No wonder old George was beered up all the time.” The two vintage Goss presses were made to run one color only: black. Hoehn, with Rube Goldberg modifications known only to him, got them to do rainbow effects in three colors. The manufacturer said it couldn’t be done; George popped a few beers and did it.

Hoehn’s crew was three pressmen, an apprentice, and a “flyboy” whose job it was to take the papers off the packer. John W. “Preacher” Hays got on as a flyboy after working downtown street corners making a half-cent a copy selling papers and a dollar a week pushing a delivery cart for a newspaper wholesaler.

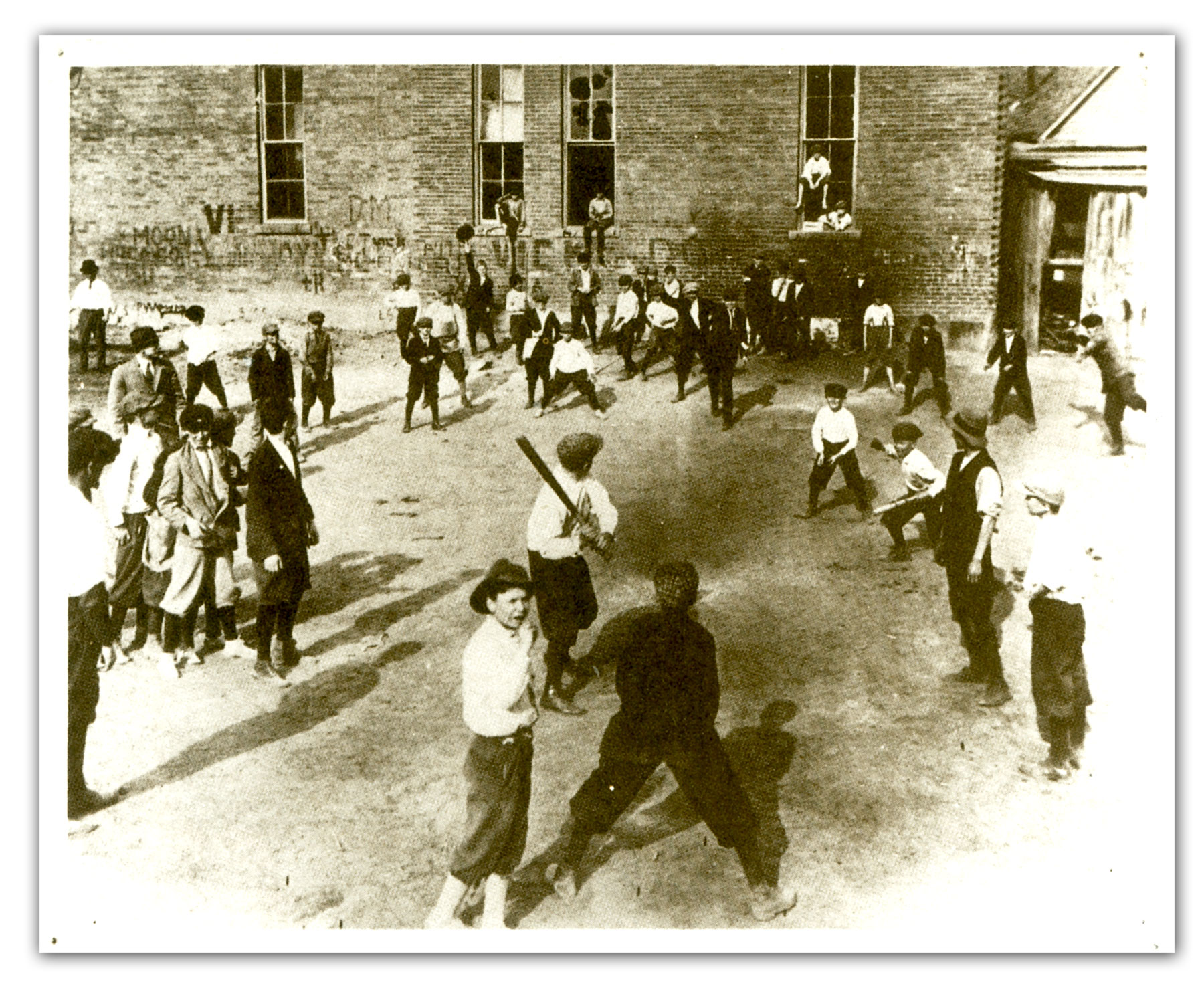

Newsboys were pugnacious and enterprising kids who were kept in line by adult Fagins called “district managers.” They really did cry out “Extra! Extra! Read all about it!” A newsboy had to be good with his fists because newsboys from competing papers took the rivalry seriously; fighting words for Dispatch carriers was the perversion of the paper’s name into “The Dallas Disgrace.” Before he established a territory a Dispatch salesman could expect to have to fight his way from one end of it to the other. I carried the Dispatch in some rough neighborhoods and have the scars to prove it.

Preacher Hays recalls his own days as a Dispatch newsboy. “We fought, wrestled, played baseball, marbles, tops, and horseshoes, and used our BB guns to shoot at windows, streetlights, weather-vanes, horses and wagons and the block policeman when his back was turned. This is how the late Bennie Bickers learned to be a world champion skeet shooter.

“Kids who liked to gamble shot craps and played poker inside the wagons of the transfer company next door to the Dispatch building. We turned out some great gamblers and a few good pimps. If you wanted to become a thief, bank robber, or safecracker, we had some fine teachers hanging around the Dispatch alley and lot. Some of our graduates were sent to prison and the electric chair. We produced the king of the safecrackers, Boochie Wallace. He could knock a knob on any safe in Texas in two minutes flat. He was later a model citizen.

“Most of this crowd turned out okay. The old YMCA Newsboys Club on Jackson Street helped us see the error of our ways.”

By 1938, it was apparent that all was not well with the Dispatch. In its best years, the paper had reached 60,000 circulation and nearly caught up with the Times Herald. It had regularly made a 6-percent return on its investment, and had stashed away a reserve fund to use when it was needed. But Scripps heirs raided this “rainy day” account to the tune of $150,000—then a sizeable sum—to put into shakier newspapers in the West. The word went out in Dallas that the Dispatch could be bought—cheap.

In 1938, Karl Hoblitzelle, the head of the Interstate Theaters chain, bought the Dispatch and the Dallas News’ afternoon loser, the Journal. The total for the two was rumored to be somewhere in the half-million range. Alfred Andersson stayed on briefly as publisher until he was replaced by Hoblitzelle’s friend, insurance executive Clarence Linz. The Dispatch’s business manager, Bill Mitchell, who later became president of Interstate Theaters, made calls on Hoblitzelle’s influential friends, major advertisers who had never placed ads in the Dispatch. “It was sad to see them turn down a man like Karl Hoblitzelle,” Mitchell says. “They were polite, but pointed out that the Dispatch was the blue-collar working man’s newspaper, and they didn’t really need it on their schedules.” Neiman-Marcus never advertised in the Dispatch. Its friends were stores like Haverty’s Furniture, Sam Dysterbach’s low-price clothing and uniform emporium, and Skillern’s Drug Stores.

Hoblitzelle and Linz tried to change the Dispatch’s image, but nothing ever quite worked. The reason, most agree, was simple: Hoblitzelle was a theater man and Linz an insurance man; neither knew a thing about either the newspaper business or the Dispatch’s working-class audience. They merged the Dispatch and the Journal into a single paper, the Dispatch-Journal, then finally sold out, in 1940, to Jim West of Houston. West put his sons, Jim Jr. and Wesley, in charge of the paper. In a misguided move, the Wests changed the name to the Journal, saddling it with the name of a paper that had always been a loser.

The newspaper struggled along for a couple of years until the Times Herald swooped in and bought up its remains. Even its final purchase price was an insult: $60,000. A feeble last edition appeared about noon on March 26, 1942. By nightfall the tiny two-story red brick building at Federal and Bullington had been stripped bare.

The Herald all but sowed the ground where the building stood with salt. The ancient presses that George Hoehn had threatened into doing his will were sold for salvage. Usable linotypes and stereotype gear were moved into Herald shops. Even the morgue and files were sold as scrap and wastepaper. The chairs, desks, and typewriters went to second-hand stores and junkyards.

There is not even a complete library of the Dispatch’s 36 years of newspapers. A few yellowing copies are in the archives of the Dallas Public Library and the Dallas Historical Society. There are other copies in the closets of former employees.

By the time of the Dispatch’s death, I had moved on, first to the Herald, which had offered a salary I couldn’t refuse ($35 a week), then to San Antonio. Alfred Andersson had retired to La Jolla, California. He and his wife are dead now. A daughter, Ruth May, lives in Dallas. His son Alf Andersson Jr. retired after a long term with the Memphis Press-Scimitar and lives in Florence, Alabama.

Terry Walsh was around for the end.

“In January, 1942, we had gone from broadsheet—it was embarrassingly thin—to tabloid form, which at least gave the paper a slightly fatter feel.

“On March 26, 1942, I was wire editor, and went to work at the normal ungodly hour of 5:30 a.m., combed through the overnight United Press reports, checked art possibilities, and began pushing copy for the first edition.

“I laid out Page 1 with a two-column picture and saw it rolled to the stereo-typers as I returned to my desk to start on the second edition. A few minutes later, C. Joseph Snyder, who had been hired by the Wests to be VP and general manager, strode by with a piece of paper in hand and disappeared into the composing room.

“When the first copies came from the pressroom, the two-column picture had been replaced by a shallower two-column box of type headed ‘An Announcement.’ The newspaper’s nine-line death notice stated that ‘continuance is no longer economically plausible and would therefore constitute waste.’

“The Times Herald’s wrecking crew arrived as I was walking out the door, stunned.”

After the presses, linotypes, and other machinery were removed, Preacher Hays was retained by John Runyon of the Herald to get the building cleaned up and to dispose of the remains as he saw fit.

Beneath a trap door leading down to a storage area under the newsroom floor, Preacher found the bound files of the newspaper dating back to Day One. “Nobody seemed to want them,” Preacher says. “I hated to do it, because I’d spent so much of my life printing them, but there was nothing else I could do. I sold them for a few lousy bucks to the American Paper Stock Company.”

Jim Chambers, Clarke Newlon, Terry and Mason Walsh, Bill Payne and Bill Mitchell all agree the Dispatch might have made it through many more years if the last managers of the paper had had more experience and vision. “It might have served as a force in the community,” Newlon says, “but starting a paper like the Dispatch today would be just about impossible. It would be too expensive. It couldn’t get features and wire services. It would be an anachronism. The Dispatch may have been the last of the personal journalism daily newspapers in America.

“We lived and worked in an atmosphere like Ben Hecht’s The Front Page,” Newlon adds. “I should have had a motto over the city desk in 120-point type: ‘Often in Error but Never in Doubt.’ We all knew exactly what was right and what was wrong, what was news and what wasn’t.”

Shortly after World War II, I got a call one day from my lawyer friend Waller Collie, who had taken delight in ambulance rides with me.

“Dallas Dispatch ink!” he yelled through the phone. “I’m covered with Dallas Dispatch ink!” He explained that the Dispatch building was being torn down for a parking lot and that as he walked by, a wrecking ball had plopped through into an ink sump beneath the pressroom floor, splashing it everywhere, including on his new ice cream suit. The Dispatch had written a postscript to its obituary.

I got in my car and sped to Federal and Bullington. The last truckload of brick was pulling away from the demolition site. I hailed the driver to a halt and paid him two dollars for 15 bricks. To each I affixed a brass plaque: “A Keystone from My Newspapering Past—The Dallas Dispatch—1906-1942—RIP.” I gave 14 of them to friends with whom I had covered the news.

Hal Lewis had his built into the hearth of his house in the country. Red Webster’s sits on a walnut base on his desk. Jim Chambers has his in the executive suite of the executioner, the Herald, and will carry it home when he retires.

I had mine displayed in the living room bookcase until an elderly newsman’s daughter called me some years ago and said her dad would give anything to have one. I gave him the last brick I had.

Get the D Brief Newsletter

Author