Woodie Woods has settled onto a huge overstuffed sofa, but it is obvious that he is anything but comfortable. Woods’ thin, middle-aged face is dwarfed by its own image, projected larger-than-life onto a 60-inch television screen in front of him. The tableau is almost Orwellian. There is Woods, staring into the screen, occasionally rubbing the fingers of his right hand across his forehead in a fidgety physical release of his nervousness. And there on the screen is his image, fidgeting on a much larger scale.

“You notice the way you’re always doing that crap?” says Woods’ host, Fort Worth Mayor Pro Tem Jim Bradshaw, who is staring only at the screen. “When you run your hand across your forehead like that when you’re talking, it makes you look nervous as hell.”

“I guess you’re right,” says Woods, withdrawing his hand awkwardly from his face and stuffing it between his left arm and his rib cage.

Bradshaw’s attention never leaves the screen. It has taken him months to assemble his private library of video tapes of Fort Worth City Council meetings, and he studies them the way Tom Landry might study game films. The fact that Bradshaw has invited Woods to his home this evening represents a gesture of support for Woods. Both men know he needs it.

Woods, who gives a new dimension to the word “timid,” has locked himself into a mayor’s race with Hugh Parmer, the shrewdest, most cunning politician the city has, known in decades. Perhaps out of sympathy, Bradshaw wants to help Woods.

“Woodie,” says Bradshaw, still staring at the video image while he talks to the man, “I’m gonna say this as your friend, okay? I mean this constructively. . . Sometimes the way you try to execute the ideas that you have . . . Well, they may sound good beforehand; they may really be the right thing to do. But when you put them to the city council they don’t work worth a shit. I guess what I’m saying is that strategy can be as important as good intentions. Sometimes it’s not so much what you feel that is important; it’s what you can sell in that council chamber.”

“You may be right,” says Woods, in a tone that sounds more like politeness than agreement. “But I just think with me as mayor, and people like you and some of the others back on the city council, we’ll have a council that can do what’s right for the city. We’ll have a real conservative council.”

“That’s another thing,” snaps Brad-shaw. “You need to drop that ’conservative’ bullshit and come up with some terminology that’s more suited to the times. If you look at the way we vote, ’conservative’ doesn’t exactly fit. Sometimes it’s conservative; sometimes it’s liberal; sometimes maybe it’s a little of both. You need to come up with something better like ’will of the people,’ or some phrase like that. You know what I mean. Work on it.”

The session in Bradshaw’s living room has taken on the tone of a halftime locker room talk, with the coach exhorting his team to gut it up, get tough, go out and win.

The more I watch, the more convinced I become that none of those things will happen. Woodie Woods will not get tough. And, without a minor miracle, he will not go out and win. He’s just too nice a guy to be tough, too honest to be cunning. He is an anomaly in politics, an aberration among his peers. Woodie Woods is the only honest politician I have ever met. That is not to say that all the other politicians I have ever known are dishonest. It is just that Woods is the only one I have ever known who is totally honest. He still operates under some concepts which have become quite novel in our society: Always say what you mean. Never lie.

I don’t understand,” Woods once told me after a lengthy Fort Worth City Council meeting that had as many plots and subplots as a soap opera, “why everyone can’t just go ahead and vote by their convictions and let the majority decide the issues. Isn’t that the way the system is supposed to work?” Poor man, I thought to myself, how can he ever survive in politics?

But that is a question I have had occasion to ask myself many times. The first time I saw Woodie Woods, I was convinced he was the most unlikely political candidate I had ever met.

It was 1975. Woods had filed for a Fort Worth City Council seat against Leonard Briscoe, a black businessman who was a popular incumbent, apparently unbeatable. The two candidates made a sharp contrast as they sat beside each other at a quiz session at the Press Club of Fort Worth.

Briscoe spoke slowly and eloquently, pausing at just the right moments to give emphasis to the points he made. Of course he never really said anything, but we reporters had expected that. After all, what politician, especially one who lacks serious opposition, is going to get himself out on a limb with well-defined campaign promises? Briscoe waltzed with the news media, and gave us quotes over which we could place headlines. He was skilled at the politician’s craft.

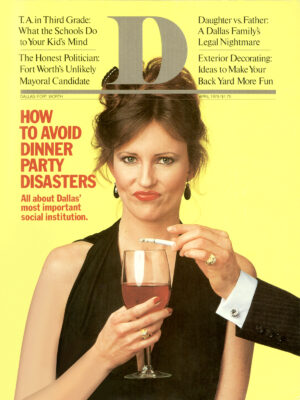

When it was Woods’ turn to talk, he CANDIDATE WOODS: Call his plumbing company on a day when council is in session, and you may have a man in a three-piece suit crawling around under your house.

was as awkward as Briscoe was confident. He trembled visibly whenever a television camera was pointed his way. Asked his political ideology, he responded with answers like “I’m an American.”

“Who is this nerd?” I asked one of my fellow Fort Worth Star-Telegram reporters.

“I dunno,” my colleague responded, “he’s some plumber who came into city hall the other day, five minutes before the election filing deadline, and signed up to run against Briscoe.”

“Oh, I get it,” I said.

It’s not unusual for small businessmen to file for a local political race merely for the free publicity. If there are four candidates in a political race, it is the policy of the Star-Telegram, and every other major news organization in this area, to give all four a chance to speak on every major issue raised. The result is that the also-rans get their names in the paper almost as much as the contenders. My initial impression of Woods was that he was just in the city council race to get his business publicized; that he knew he couldn’t win; that Briscoe would bury him on election day; and we could all soon forget him.

I was wrong.

A couple of weeks before election day, a civil fraud suit was filed against Briscoe, seeking repayment of about $300,000 in alleged bad debts. The suit made a conspicuous headline on the front page of the Star-Telegram the next morning. It was trial by media at its best. Briscoe’s reelection chances went down in flames. And Woodie Woods, who more or less randomly chose Briscoe to run against, was swept into office by a 3-to-1 margin.

I shall never forget the look on both candidates’ faces on election night. They were equally surprised. Woodie Woods, perhaps the least prepared candidate to file for office in years, suddenly had a stronger numerical mandate from the voters than anyone else on the Fort Worth City Council. Briscoe was stunned, but no more so than some of the candidates who’d entered races for other city council seats.

“I just can’t believe it,” said one losing candidate who’d spent $10,000 trying to win another at-large council seat. “Why didn’t I get in the race with Briscoe? If I’d only had the luck of that . . . that . . . plumber. I could have jumped in the race with both of them and won without a runoff.”

It didn’t take Woodie Woods long to become a folk hero. Shortly after his first term began, it dawned on most around him that by accident, the voters had elected an incredibly sincere man. Woodie Woods was not dumb, just overwhelmingly humble. Woods genuinely believed that government should be made up of regular citizens. It was a little shocking to veteran political reporters to find that Woods, as a city councilman, did not think he was better than average people. He still thought he was one.

Most incumbent politicians, even at the city council level, have a fantasy like this one: The phone rings at the officeholder’s home one night. A voice at the other end is calling from Hollywood. “Sir, this is Freddie de Cordova, producer of the Johnny Carson Show. We’ve watched you in the council chambers and, well, what can 1 say? You are so astute, so clever, so sophisticated. You deserve to be on our show. America will love you.” Politicians read newspaper accounts of their meetings the way actors read their reviews. They tape themselves on television. They pop the channel selectors back and forth on their television sets during the 10 o’clock news, trying to get just one more glimpse of themselves. It is ego, not lust for power, that is the driving force behind local politics.

It is the recognition of that fact of political life that made Woodie Woods appealing to the media from the moment he took office. Inexplicably, Woodie Woods’ ego did not grow to fit the position he held.

But it wasn’t Woods’ humility that made him extremely popular with his constituents. It was the fact that this reticent plumber turned out to be relentless in his pursuit of the rights of the little man. That pursuit wasn’t based on altruism. When Woods was championing the cause of the little man, he was fighting for his own cause. Although Woods seemed in his early days of office to be mortally afraid of a television camera, he showed no shyness in doing battle with the representatives of Fort Worth’s ruling class. His lack of sophistication often was an asset in the course he was to follow.

Once, after hearing several weeks of elaborate testimony in a electric rate case, Woods responded with a proposal that was simple horse-trading. “1 move,” he told his council peers, “that we just give them one-half of the rate increase they are asking for.” The proposal wasn’t based on any sophisticated formula. Half just sounded like enough. Woods’ motion died for lack of a second. The rate increase proposal which the council granted was passed with Woods, still undaunted, voting against it. Half still sounded good enough. Votes like this sometimes made Woods unpopular with his fellow council members, but it made him overwhelmingly popular with voters.

His lack of awareness of the ways of politics sometimes made him immune to the political gamesmanship practiced at city hall. Three years ago, after a lengthy debate by the council on the contents of a city bond proposal, the proponents of the bond package decided to run over Woods with a power play.

A resolution was offered that would put the council on record as urging the voters to endorse the bond package in its entirety. Woods had opposed the bond funds for the Fat Stock Show and Rodeo, an organization he considered to be more a club for rich people than a benefit to the taxpayers. “We thought we could fix his wagon on that resolution,” one of the council members later told me. “The way it was worded, you had to be for the whole package or for none of it. Anybody who was against it would look like they were against Mom and apple pie.”

Woods, however, didn’t understand the subtleties of the measure. He just evaluated it on its face. When the vote was taken; he cast the lone “no.” What was to be a vote of confidence, a public record of the council’s solidarity, turned into a disaster for its backers. Instead of going on record as totally behind the bond issue, the council had put itself on record as having mixed emotions about it. Voters ultimately turned down major sections of the measure. Proponents of the bond package blamed Woods.

In many ways, Woods made himself an outcast among his council peers during his first term of office, but he had developed a real power base by resisting the city hall status quo. The fact that massive numbers of voters seemed to agree with him about the bond package was the first evidence of that power base.

The seeds of Woods’ independence were sown, almost accidentally, during his first election campaign. Woods never really thought it would take much in the way of campaign funds to get elected. After all, he reasoned, the best candidate will win. So if I am really not the best candidate, it just doesn’t seem right to spend money to try to get elected anyway. Consequently, Woods decided not to accept any campaign contributions. He financed his election campaign, which cost about $3000, out of his own pocket. “I just wouldn’t have felt right asking people to spend their money on me,” Woods recalls. When he won, Woods found himself in a rather unusual position for an incumbent. He had no political debts to repay.

One day during his first campaign, he got a call from a local banker. “I want to give you some support,” the banker told Woodie.

“Gosh,” said Woods, “I would really appreciate your vote. Every vote counts, you know.”

“I’m not talking about that,” the banker said. “I live in Westover Hills. I can’t vote for you. I mean support; money; campaign contributions. How much money do you think you are going to need?”

“Aw, I don’t need money,” Woods said. “I hadn’t really planned on spending money on this campaign.”

Perhaps Woods believes in such fairytale concepts as low-budget or no-budget election campaigns because of his business experiences. Woods the businessman is one of those rare success stories that defy the law of averages: the truly self-made man.

Woods, who as a youngster had to work to help feed himself, dropped out of school in the seventh grade. After a stint in the Navy during World War II, he came back to Fort Worth thinking he could get ahead if he could just find a good trade and work very hard at it. He went to work for a plumber, more for the experience than for the money he could make initially. Soon he and another young plumber decided to start their own business. They succeeded by being willing to do jobs other plumbers wouldn’t accept and, ironically, showing customers how to perform minor repairs for themselves in order to save money. “It’s just not right for somebody to pay a plumber to fix something if the problem that needs fixing is something the homeowner can repair himself a lot cheaper,” Woods maintains. That belief made him unpopular with his fellow plumbers. “Some of them really turned a cold shoulder to me at first,” he recalls, “but of course that was years ago when plumbers around here were kinda clannish.”

Since then, Woods has worked his way to the top. He now owns three plumbing shops, and is considering opening a fourth. He has about 20 people on his payroll, none more active than Woods himself. He’s the only man in Fort Worth who drives a Mercedes with a pipe wrench on the console. It is not unusual, as I found out by following him around one day, for Woods to go from a city council session to a plumbing job. Call Woods’ plumbing service on a day when the council is in session and you may find a man in a three-piece suit crawling under your house.

By the end of Woods’ first term as a city councilman, he had gone from being a nobody to being an institution. He was re-elected easily. Nobody could unseat Woodie Woods in the council district he represented under Fort Worth’s newly-formed single-member district plan. He had become a paradox. As a person, he was still quiet, shy, almost fragile. But as a politician, he was essentially invincible. Even though he had attracted some tough, well-financed opposition by his ongoing war against the city’s establishment, he was firmly cemented into office.

But Woods also became part of an unlikely alliance. Woods, the populist plumber, found his only ally in City Councilman Hugh Parmer, his antithesis. Partner is Yale-educated, articulate and astute enough to know that political power comes from beyond the confines of City Hall. He knew the course that Woodie Woods was following made him more popular than all of his more refined council peers combined.

Parmer also saw Woodie Woods as the perfect political patsy. It was easy to talk Woods into doing dirty political jobs, taking unpopular positions on the council that would advance Parmer’s strategy. Parmer could lie back and let Woods be the weathervane. And because Woods’ public image was so wholesome, it was hard for Parmer’s opponents to retaliate by attacking Woods the man. The only problem was that Woods, politically naive as he was, didn’t know what Parmer was up to.

“I think Hugh just knows what the people want and he wants to give it to them because that’s the right thing to do,” Woods told me one day during the height of their alliance.

“What would you think,” Parmer once asked me during a discussion of his strategy for an upcoming council session, “if Woodie Woods proposed lone motion) and then I circled back and played the moderate, proposing [another motion]? It would be like the Battle of Hastings. Double envelopment. I’d have them” – his council opponents – “where they couldn’t get away.”

I was convinced at the time of that conversation of two things. One was that Woods, at that point, did not even know about the idea he would later propose at the council session of which Parmer spoke. And that Woods would never know he was a part of a reenactment of the Battle of Hastings. He’d just think he was at a Fort Worth City Council meeting. And when I saw Parmer’s strategy actually carried out before the council, I knew just how effective the Woods-Par -mer alliance was – for Parmer.

When Parmer ran for mayor two years ago, Woods broke with City Council tradition by publicly endorsing Parmer in his bid to unseat Mayor Clif Overcash. Fort Worth City Council members never endorsed other candidates for office, until then. Parmer won an extremely close race with Overcash. Parmer strategists felt that Woods’ endorsement was crucial, perhaps the deciding factor in the election.

But the alliance that worked so well for Parmer was ultimately to go sour. Woods began to question, at first to himself, the bitter, polarized political environment that had developed at City Hall under Partner’s administration. As Woods watched the city manager, city attorney, public works director, city budget director, and a handful of assistant city managers and city attorneys resign during the two years after Parmer took office, he began to think that perhaps there was something wrong with the Parmer administration.

The breaking point came one day when Woods declined to vote the same way Parmer did on a motion being considered by the council. Parmer was furious that Woods had stepped out of line.

“Hugh showed up at our house that night at 9:30 and started in on me about not supporting his motion,” Woods recalls. “It was the first time Hugh Parmer had ever been inside our house. He kept telling me ’I don’t have many friends, but I have to have complete loyalty from those I do have.’ I kept trying to tell him that I just happened to disagree with him on the proposal that he had made and that I thought the whole idea was for everyone to vote by his convictions.”

The relationship went steadily downhill.

“Now Hugh doesn’t talk to me much anymore,” Woods says, “and when he does talk to me he always calls me ’Mr. Woods’ instead of ’Woodie.’ “

After the rift became obvious to others, Woods began getting calls from some of Parmer’s opponents. Wouldn’t he consider, they asked, running for mayor against Parmer?

“I told them I wasn’t all that interested in being mayor at first,” Woods said. “1 said I thought there were just plenty of people in this town who would make a fine mayor, who could do the job a lot better than me or Hugh. But they told me that they had taken a poll and it showed’ that I was the only one who could beat Parmer.”

Woodie’s wife Jewel, however, was the one who finally made the move.

“Darndest thing I ever saw,” Woods recalls. “Jim Bradshaw just came up to Jewel one day in the city council chambers and said, ’You know that Woodie is the only person who can beat Parmer. You ought to think about running for mayor.’ She told him, ’Oh, didn’t you know? Woodie is planning to run.’ At the time she said that, we’d never even discussed it.”

There is little doubt in the minds of those close to Woods that he could have never made his ascent to political power without his wife Jewel. She is as aggressive as he is shy. She is always behind him, pushing in just the right manner to help bring out the potential in this reserved man. The relationship works well. It is also well known in Fort Worth political circles.

But Woods, by then, was convinced that someone had to take the mayor’s office away from Parmer. “I finally decided that if someone was going to do something about what is going on at City Hall right now, it’s going to have to be me,” Woods says.

Now Woods, at 58, is getting the political education of a lifetime. It is beginning to dawn on him that he could use a well-orchestrated, well-financed campaign.

While Parmer runs phone banks with as many as 30 persons making calls at a time, Woods and his wife sit licking a small pile of envelopes, inviting people to share cornbread and beans with Woodie at a cafeteria. Parmer has a public relations firm on contract and a professional campaign strategist he brings up from Austin every week, not to mention the resources of his own marketing firm. Woods has the services of an insurance man and his wife, one secretary, and a few piles of postcards.

Members of the Parmer camp are beginning to size up Woods like a trophy to be stuffed and mounted over the mayor’s mantel.

“I can tell you right now that Woodie doesn’t have a chance – not a prayer,” says Jim Kitchens, one of Parmer’s strategy staff. “But there’s still some contest in it for us because Hugh wants to win big to build up his political base for something else down the road.”

It will be great sport, Parmer’s backers contend, for Parmer to knock Woodie flat after about three rounds, just to show everyone what a contender the mayor really can be. Some of Parmer’s supporters are even beginning to have fantasies about a bid for the governor’s office in 1982.

Woods, however, does not realize that his candidacy is merely a sparring match for Parmer. Woods thinks he is in a mayor’s race.

“I honestly believe that I am going to win,” Woods tells me as we drive to a plumbing job in his Mercedes. “I think the people of this town want a little bit of harmony on their city council for a change and I think I will be able to give that to them. When you get right down to it, elections are just a matter of choosing the candidate who is best qualified to give the voters what they really want. Isn’t that right?”

I smile and nod, thinking all along how badly Parmer will flatten Woodie Woods on election day. I hate to see anyone get stepped on.

More seasoned political veterans, like Jim Bradshaw, apparently share that compassion. That’s how Woods found himself in Bradshaw’s living room one evening, invited over for a little session on the art of politics.

As the evening wears on, Bradshaw tries to give Woods advice on how to throw a few punches of his own at his opponent, how to get in the ring, politically speaking, with horseshoes in his gloves. It will take money to win, Bradshaw tells1 him.

Woods listens attentively and politely to his would-be mentor.

“Yeah, Jim,” Woods keeps saying. “You are certainly right. I’m just going to have to do some of those things.”

When the evening concludes, I find myself climbing into the Mercedes with Woodie, his wife, and his pipe wrench.

“I can’t do all that,” Woods says, thirty seconds after we drive away from Bradshaw’s house. “Politics isn’t worth having to get nasty over. . . .And I’m notgoing to go and spend a whole bunch ofmoney, either. That just wouldn’t beright. . . .I guess I’m just going to have towork a little harder and win the raceanyway.”