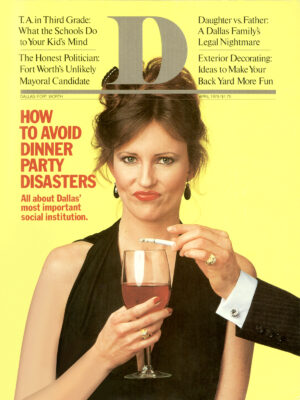

The dinner party is the oldest social institution in Dallas. John Neely Bryan, the shadowy figure who founded and named the town, started the tradition. On hearing the sound of hoof or wheel, he was said to rush from his dugout and virtually pull the traveler off horse or wagon, force a gourdful of whiskey and a plate of bear meat on the guest, and sell the virtues of Dallas as a place of residence.

Today, despite the competition from gourmet restaurants, clubs, discos, and society benefits, the private dinner party remains the standard of entertainment in Dallas. In other words, you haven’t really cracked a social circle, you haven’t impressed the leadership, until you’ve met your peers across the dinner table and can oblige them to attend your own. It’s as simple as that.

“It’s where the young learn manners,’’ claims a Dallas grande dame, commenting on the deplorable decline of taste (one younger Dallasite was recently given such a lesson when dowager Kenneth Horan Rogers kicked him under the table when she saw him blowing on a spoonful of hot soup.)

The dinner party is one thing we all do. We don’t all work, we don’t all watch television, go to Cowboy games, attend the theater, play poker or duplicate bridge, fish or ski. . . but we all go to dinner parties. Despite its importance for ladder-climbers of all persuasions, shapes, and ages, the dinner party must be faithful to its purpose: Make a memorable evening. And in Dallas there have been some damned memorable evenings.

For every generation, the Golden Age of dinner parties was “yesterday.” In the 1890’s, the name of Mrs. Jules Schneider was synonymous with dinners worthy of Newport. Her Dallas mansion had three kitchens, and she stole her French chef from Sarah Bernhardt. Her staff wore livery when the occasion demanded, and she kept an orchestra under contract to play for her exclusively.

Today the 1950’s linger in many minds as the last Age of Golden Dallas dining. And no hostess was more stylish or elegant than the late Bert de Winter. Bert was head of millinery at Neiman-Marcus when women’s hats brought in the kind of money furs bring now. She was a power, both at the store and on the social scene. An exotic lady, she sent her dry cleaning to be done at The Ritz in Paris, and her home on Amherst was color-coordinated from front curb to rear cupboard. Female guests planned carefully what to wear to a de Winter dinner party because her formal dining room was walled in rich red moiré silk.

Her invitations were command performances, but invitees went for the thrill of the evening more than from obligation. Her lists were select. As a hostess, Bert de Winter didn’t suffer interference. Her dinners were orchestrated, and she alone held the score. But one Dallas woman, even today, shudders at what happened to her at a Bert de Winter dinner.

The woman was pregnant; she was, in fact, a month overdue. Ordinarily a sensational beauty, she remembers feeling like a frump. (Bert de Winter had never done anything so inelegant as having children.) But on this Sunday, Bert called to invite her and her husband over for “just a little supper, darling,” with a male friend of Bert’s who came regularly to Dallas to see her. The pregnant woman, pleading everything from physical wretchedness to wretched maternity wardrobe, finally allowed herself to be persuaded, assured by Bert there would only be the four of them – the pregnant woman knowing that Bert was more interested in her husband than in her.

Drinking began at 5:30 p.m. By 6:30 an additional sixteen guests had arrived. Bert, as usual, was right off the pages of Vogue, and so were the other female guests, who hadn’t for a minute believed Bert’s “just a little supper” line.

By 8:30 dinner had not been served or even hinted at, and the handsome young husband was taking a pronounced tilt to windward. By 9:30 he was, in a few words, falling-down drunk. The guests, in their elegance, and the pregnant woman in her dowdiness, were finally ushered into the formal red dining room and seated for dinner at 10:30 p.m. Just as the first course was being served, the woman felt her labor pains start.

An older woman, seated across the table, suddenly whispered, “I want to see you for a moment.” They retreated to a bedroom where the older woman said, “You need to go have a baby! Admit it.” She could only nod in reply. Marching back to the dinner table the older woman asked for the husband. He was in a near-hopeless state. “Somebody’s got to drive this girl to the hospital,” the older woman announced. Bert de Winter muttered something which the woman to this day thinks was “Can’t she wait?” The young husband stirred and slurred and proclaimed he could do it and, by God, he would do it. Despite protests, he left the party with his wife – and promptly fell asleep behind the wheel of the car. The desperate woman pulled him away and drove herself to the hospital, admitted herself, and (of course) had the baby herself, while the husband slept it off in the parking lot. The hospital sent someone out to get him when the baby arrived, but he couldn’t be stirred. He saw it next morning.

“Bert never forgave me for breaking up that dinner party by dragging my husband away,” the woman says today.

ometime in the mid-Fifties, when Stan Slawik had begun revolutionizing Dallas dining-out with his Old Warsaw Restaurant, Bonnie Leslie persuaded him to take a night off and come to her dinner party. Mrs. Leslie was using a young cook from the Zodiac Room who had shown some cleverness, and she hinted that Slawik should note her discovery’s flair. But it made the cook so nervous to think the famous restaurateur would be in attendance that by dinner time he was all brandied up. He wildly slapped things on the plates (no vegetable for one, no meat for another), humming off-key all the while – and finally staggered out of the kitchen and into the night, not to be seen again.

But the most famous dinner parties of the Fifties featured not the cook, or the hostess, or even the food, but the house. Mrs. Bruno Graf’s mansion on Park Lane was designed by Edward Durrell Stone and was said to be the finest residential work by that architect. Stone designed the house with a water motif, and the dining table sat on an island surrounded by a moat.

Karl Hoblitzelle, the courtly, immaculate head of Interstate Theaters, was bowing the hostess to her chair at her first dinner party when, plop, into the water he went. One of the waiters was robbed of his tuxedo in order for Mr. Hoblitzelle’s evening to continue.

A few nights later, at a benefit dinner for Dr. Tom Dooley and his Medico mission, three guests in a row, beginning with Mr. Tayloe of Sears Roebuck, took unexpected dips while shaking hands in the receiving line. One very pretty woman disappeared for a moment, leaving only her pink straw hat and her pink straw bag floating to mark the spot. Mrs. Graf finally conferred with former victim Hoblitzelle, who dispatched some velvet ropes from the Palace Theater to mark the water’s edge.

Dinner party mishaps continue. Only last year, a late-departing guest couldn’t find his new Porsche. Next day it was discovered in the host’s swimming pool. One of the guests confessed she had seen the car resting on the bottom of the pool the night before, but had thought it was part of the fabulous decor. “The pool lights were on, but I’d lost one of my contacts and was having to look with one eye,” she said.

Another automobile story involves a Dallas couple of the Sixties. Although their marriage was in trouble, the husband, as a surprise, gave a dinner party on their anniversary and presented his wife with a new Rolls-Royce. The gift annoyed her. She was in no mood to patch things up. The dinner proceeded through several cocktails, several wines, and several champagne toasts. Suddenly she stormed out of the house, climbed into her new Rolls, and drove off. Next day she returned home by taxi. It took her husband two days to find the Rolls in the parking garage of the high-rise where her lover lived. In Houston. The marriage broke up, but she learned to love the Rolls, and for several years gave a dinner party of her own on the anniversary of acquiring it.

He literary dinner party, not as popular in Dallas today as it was a decade or so ago, brought some of America’s most-read authors to the Nonesuch Road home of Stanley and the late Billie Marcus. The Marcus’ dinner parties deserve at least a few footnotes in literary history. Once they were entertaining New York publisher Alfred A. Knopf when the talk turned to wine – as it often did when Knopf was present, since the publisher considered himself a wine expert. Stanley Marcus mentioned a recent story in The New Yorker by a British author, Roald Dahl, which had been cleverly, and expertly, based on a blindfold wine tasting.

Knopf hadn’t seen the story and was intrigued by the conjunction of two of his interests: good writing and fine wine. Marcus found the magazine, and while the other guests pursued cigars, brandy and powder rooms, the publisher read the story. He was so impressed that he immediately got on the phone to an editor and ordered him to find Dahl and offer a contract. A. A. Knopf Inc. brought out Dahl’s first volume, thanks to a Dallas dinner party.

Dallas authors also got the chance to meet celebrated publishers at Marcus dinner parties. Lon Tinkle and I once cornered the late Bennett Cerf, of Random House, in Marcus’ museum-like “Fertility Room” (so called because of its collection of totemic figurines) and sold him on the idea of a Texas book, which we made up on the spot. Cerf was so taken with the plot that when he returned to New York, he sent back a contract and a nice advance. Unfortunately (perhaps) for Texas letters, Cerf died before the book was begun. The advance is long spent and the book has not been written to this day.

The dinner party has always been an act of personal expression. Ruth Spence, whose wise view has taken in seven or eight decades of Dallas, says food is less important for its success than the meeting of intersiing minds.

When her husband, Alex Spence, was alive, they settled on eight as the ideal number of guests. “I felt like twelve was just too many, and a great number of times you must add a guest or two at the last minute.”

But talk was the basis for her dinner parties and is the basis on which she judges those she goes to now. “When Alex and I closed the door on our last guest, we told each other, ’It was a good evening,’ if we had had good talk.”

Ruth Spence’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Wendell Spence, kept the table set for dinner and always gathered interesting people. She had an excellent staff, and she was prone to invite people on the spur of the moment. When she came back from shopping, the cook would often inquire, “Mrs. Spence. . . how many extra people did you ask when you went to the book store?”

But Ruth Spence doesn’t accept her earlier years as the Golden Age of Dallas dinner parties. “Young people in Dallas today do remarkable things in the way they handle entertaining without help,” she says. Of course, there are certain modern hazards. “We inherited a lot of very lovely serving items,” a Highland Park hostess says, “which stay in the vault, regardless of whom we have for dinner. We can’t show the silver, under our insurance policy.”

The dinner party affords a certain amount of opportunism, too. “How many careers started up the ladder in Dallas last year when the boss took the junior exec’s wife into the library – or the sauna?” a corporate wife asks somewhat bitterly.

Dinner party dalliance took place even in the Fifties. One new bride was brought to Dallas to meet her husband’s family. At a party given by the husband’s grandfather, she was seated between two charming uncles. Suddenly she felt herself being groped, from both sides, under the table. She spent the evening fighting off male in-laws, including her new father-in-law. She was informed, when she got up the courage to protest, that it was a family tradition.

More recently, lust overcame professionalism when a hostess, famous for getting drunk and, when drunk, getting seduced, became the center of a tug-of-war. Her husband spent the evening trying to keep her off the sauce while her psychiatrist spent the evening trying to get her on it. Both claimed it was for her own good. The husband was furious and thought she ought to change psychiatrists; the psychiatrist was furious and thought she ought to change husbands. She is reported to have done one or the other.

Not all dinner parties are viewed with unmixed pleasure. Corporate “must do’s” have a bad reputation. One ex-corporate wife complains, “You are not being invited for you. The power is aimed at the man. The thing that’s missing at most dinner parties is freedom – you have no freedom to be yourself, you are free only to be as you are prescribed to be. You are there for a reason. . . who you are as a person, nobody cares; nobody wants to know.”

Possible exceptions to business dinner doldrums were those given by Neiman-Marcus during the Marcus family regime. Or possibly not. “Everybody went-sick, dead, pregnant,” an ex-Neiman-Marcus wife says. “Store dinners were all command performances.” To be sure, the guest of honor was always famous. Neiman-Marcus brought just about anybody the store chose: Alistair Cooke, Grace Kelly, Emilio Pucci, Gore Vidal, Sophia Loren. “Of course,” another ex-Neiman-Marcus wife comments, “Mr. Stanley was like the Ayatollah Khomeini. . .he’d cut your hands off if you failed to attend.”

The business of Dallas being business, lots of it gets accomplished at dinner parties – all kinds of business at all kinds of levels. Bill Clements is said to have decided to run for governor at a dinner party. Ted and Annette Strauss like to give big political dinners for practical and political reasons, so an intimate dinner invitation from them is treasured for its rarity. The president of Southern Methodist University almost never gives a personal dinner party; they are always school functions. “How can the president of a private school have any private friends?” a former private school president’s wife moans.

Today, Margaret McDermott has kept the dinner party at its proper level, according to a contemporary, even when she’s giving it on behalf of someone or something else, as is often the case. A good many institutional and academic jobs were obtained (and a few lost) at dinner parties she and her late husband Gene gave at their Highland Park home. Now, for her intimate dinners, she generally chooses her farm at Piano. Among male friends she is rather infamous for running out of food. “Margaret eats so little herself, she forgets about men’s appetites,” one man complains. The wine is, of course, the best.

Stories of dinner party disasters abound – God knows how many cats have leapt on how many tables and eaten how many tins of freshly opened caviar – but a few disasters have been planned. The late Eli Sanger was a notorious practical joker, married to a cool, blonde woman named Claudia whose code was “never crack.” Once, before a particularly stiff dinner party, he collected all the broken china the Sanger Brothers store had from a year and bribed the butler to come in from the pantry and drop the whole mess. The effect on the guests was sensational: wide-eyed pandemonium. Claudia alone sat without giving the butler (or Eli) a glance.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte