What to do about Central Expressway, that sclerotic artery?

A modest proposal: Nothing.

People look at me oddly when I say that. And I say it a lot because people bitch about Central a lot. But I mean it.

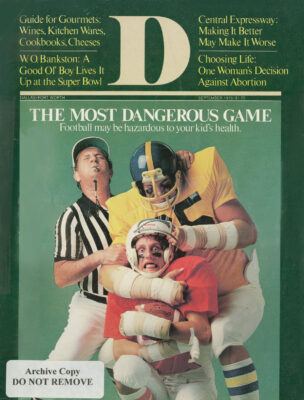

Forget the bright ideas that bureaucrats and politicians have scattered before us to make us think they are actually going to do something about Central Expressway. Forget widening, double-decking, making it one way at rush hours, putting tolls on it, taking trucks off of it, checking its flow with computerized barriers, hauling off wrecks with helicopters.

Leave it alone. Every proposal to “improve” Central is an invitation to environmental, social, and economic disaster.

Freeways are destroyers, centrifugal forces that fling blue collar workers to one suburb, professionals to another, single people to apartment complexes, old people to “retirement villages,” blacks and chicanos and poor whites to their several ghettos. The freeway floods the city with cars and the air with hydrocarbons. It is ugly, expensive, and deadly.

The alternative, of course, is public transportation. Unfortunately, city planners romanticize public transportation, forgetting how depressing it can be to actually ride it: the waits in the cold rain, the rude and jostling crowd, the hoods and bums. The freeway is freedom: absolute mobility, home to office with no waiting, floating along in air-conditioned solitude, boogeying to “Night Fever” with your free foot or being cosseted by the chatter of Ron Chapman. No wonder people love it.

They even love Central Expressway. They won’t admit it, and they curse its short entrance ramps, its bottlenecks and rush hour jams. But according to the state highway department, 228,000 of them love it enough to use it every day, most of them for short trips – not to get from home to work, but to run down from Royal Lane to NorthPark to pick up some pantyhose without suffering the indignity of traffic lights. If a freeway is there, people will use it.

Actually, Central wasn’t supposed to be a freeway. It grew out of the master plan for Dallas drawn up by George Kessler in 1910. It was supposed to be a boulevard on the former right-of-way of the Houston & Texas Central Railroad, linking the Park Cities with downtown. Dallas voted $450,000 worth of bonds for it in 1927. Depression and World War intervened, and by the time the city got around to it again, the postwar highway boom had begun. So in 1948, when work on Central began, the Morning News observed that “Central Boulevard has grown from a comparatively modest project into a super expressway, largely at the insistence of the state and federal highway agencies as the price of their participation.”

By the time the first stretch of Central opened between San Jacinto and Fitzhugh in 1949, the News was dazzled: “New Expressway is World Wonder,” it gushed in the headline of an editorial that proclaimed that “with the opening to traffic of the two-mile stretch . . . Dallas has reason to be proud of an engineering structure that has already excited interest as far away as Paris and London . . . As of this hour, Dallas can claim the finest expressway in the world … a marvel of the motor age.”

But by 1954, the Times Herald was observing that Central Expressway, still only partially built, was “almost at the saturation point in usage.” Rather wistfully, it noted that “strangely enough, almost all other major streets in the area remain congested in spite of Central Expressway’s big load. Meanwhile, the street railway is begging plaintively for patronage.” The street railway went out of business two years later. One wonders how long it took the Herald to figure out that the other major streets were congested because (1) trattic from an expressway has to go somewhere and (2) people were avoiding the big load on Central.

“The fact that it is overcrowded,” the Herald also commented, “shows how badly it was needed.” That’s like saying that the fact that the patient died shows how sick he was. No matter that the cure might have been worse than the disease. Or that there might have been other cures.

But that kind of thinking – “because it’s bad, we need more of the same” – is still in operation. That proposals to double-deck or to widen Central are taken seriously shows that the freeway is still the path of least resistance.

It doesn’t take an Environmental Impact Study to show that double-decking would be an environmental and aesthetic disaster. The best that can be said for the design of the old Central is that much of the roadbed is below the level of the city’s streets. Where it is elevated – as at the Hall Street intersection, where boarded-up shops and a housing project flank the concrete barrier – you find the kind of urban blight that could be anywhere from Newark to Watts. Imagine such a grisly barrier from downtown to LBJ, looming over pleasant neighborhoods like the McCommas-Monticello area. Double-decking and widening mean more noise, more pollution, and more traffic spilling over from the expressway into side streets. Expressways never relieve traffic; they create it.

The social impact of a more effective freeway system should also be obvious. The evacuation of Dallas into the suburbs can only be accelerated by freeway improvements. The proposed Housing Plan for the City of Dallas, now under review by the city council, shows that the population of the city has “stabilized” at about 860,000. But the city is losing families with children to the suburbs. And for every person added to the population of the city since 1960, 11 were added to the rest of Dallas County. Some of this movement reflects the mess the school system has fallen into. But a lot of it reflects the allure of suburbia created by a freeway system that provides mobility for commuters.

There is land available for housing in the city. The entire southeast quadrant of Dallas is underdeveloped, because both developers and homebuyers regard it as poison. Its bad image and underdeveloped status won’t change as long as suburbanization is encouraged.

Downtown proponents of an improved Central seem to forget that Central is a two-way street, it gets people downtown to work, but it also takes them home. And if home is Piano, that means tax revenues going somewhere else, tax revenues that we need to keep up the Dallas streets that people from Piano drive on. In fact, down-town is thriving to the extent that office space is leased almost to capacity, there is a crying need for hotel space, and there is even talk, for the first time in years, of developing residential space there. With young professionals moving back to East Dallas and Fox & Jacobs developing residential areas near downtown, there will be a living and working environment that doesn’t need freeway access.

Freeway access, in fact, can only blight downtown. As far back as 1951, the Regional Plan Association in New York studied the commuting trends in Manhattan. It discovered that in 1930, before major freeway development, there had been 301,000 commuters coming into the city daily. By 1950, there were 357,000 – an increase of only 19 percent. The major change was in the way they were coming. Railway commuting had declined sharply; automobile commuting was up from 38,050 persons in 1930 to 118,400 persons in 1950 – a whopping 321 percent. Furthermore, the study commented, “The automobiles required to transport the equivalent of one trainload of commuters use about four acres of parking space in Manhattan, eight times the area of the Grand Central main concourse.” A study of land use in central Los Angeles in the early Sixties found that two-thirds of the land was taken up by streets, freeways, parking lots, and garages.

It’s obvious that downtown Dallas is tun of parking lots, and that the parking problem is a hindrance to its development. It is the one major drawback in the re-use of older structures like the Mobil Building, whose lack of on-site parking makes it a hard commodity to market. A recent study by the state highway department shows that only 15 percent of the cars that travel southward on Central wind up in the central business district, and that 75 percent of the cars on Central have only one passenger in them. Clearly, if the intent is to get people downtown, the best method of doing it is efficient mass transit.

But most damning of all the arguments against improving Central is cost. Double-decking seems to be dead not because of its environmental impact but because the last estimate on the project was in excess of $150 million. Proposals to widen Central are still around, though the estimates on that project are around $80 million, and since the fringes of Central have been commercially developed, no widening project could avoid swallowing up some very expensive land.

Both double-decking and widening would involve long-term dislocation of traffic during construction, of the kind likely to have disastrous effects on businesses in the area. When “improving” Greenville Avenue took longer than anticipated last year, many small neighborhood shops went under. The stretch from Mockingbird to Belmont is only beginning to recover. Because Central’s bridges are too narrow to allow extra lanes to be built under them, each intersection would have to be closed during construction. Imagine what would happen to the businesses on Mockingbird near Central if that intersection had to be closed until a new bridge was built.

Of all the ways of getting people around cities, freeways are the least flexible, and therefore the least cost-effective. Once a freeway reaches capacity, which .in a high-density corridor is usually the moment it opens, there’s nothing you can do to increase its capacity other than add more lanes – which then reach capacity instantly. Almost any kind of mass transportation system is more flexible: you can add trains and railway cars to a rail system, buses and new routes to a bus system. So it makes no sense whatever to spend $80 to $150 million on improving Central Expressway as long as mass transit is a possibility.

The problem with mass transit in the freeway age is that the freeways have lowered population densities so that the models – the rail transit systems of New York, Boston, Paris and London – are no longer appropriate. And low-density, suburbanized cities that have attempted to develop mass transit systems after the freeways had taken their toll have been plagued with problems. In San Francisco, Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) was the panacea proposed for the ills of a freeway-choked city. BART has not only been a financial disaster, it hasn’t solved the freeway congestion problem. When it went into use in 1972, there was no appreciable decline in freeway use. The commuters it took off the roads were replaced by other commuters, sometimes by the housewives whose husbands had been taking the car to work but now rode BART instead.

Still, the only proposal that makes sense for Central now is the bus transitway, a project initiated in the June bond election, that would allow buses to run from Park Central to downtown in 11 minutes, The city’s worst fear is that the freedom of the freeway will continue to exert its allure and the buses will be empty.

What price freedom? If it’s $80 million,a declining tax base, blighted neighborhoods, more pollution and noise andtraffic, it’s too high. Forget it, and learn tolove Central as it is.