When Connie arrived in Dallas a few years ago she came with hair on her legs and Brooklyn in her mouth. She and her boyfriend moved in with her brother and his male lover. They sat around their digs in Oak Lawn and smoked pot and plotted a gay revolution. Occasionally they would crank up a 1947 Buick and drive about delivering propagandist circulars. They lived on welfare and cursed the fates that had brought them to the bank vault on the Trinity.

Connie was tender in years, just turned twenty, but tough and skeptical and foul-mouthed, hell on her man. I pegged her as a tomboy, until the day at my farm when she refused to relieve herself because 1 had no bathroom. She made her boyfriend drive her to a crossroads gasoline station. They did not come back and I lost track of them.

The other day I was savoring (not buying) the larder in Simon David’s when 1 came upon a lady filling her cart with the most exotic and expensive delights, all very British: James Keiller & Son’s rough-cut lemon marmalade, Bender & Cassel Ltd.’s genuine bird’s nest soup. She turned and smiled and fell upon me in greeting. We talked for a good while before it came to me that this was Connie. Her voice was soft, her hair coiffured, her nose was bobbed. Her face glowed with cosmetic care. She wore a tailored wool suit with Italian boots, a silk scarf about her neck.

The transformation was astonishing. She now lived in a stone duplex on University. She was engaged to a gentleman, an older man from California who was a partner in one of the up-and-coming ad agencies here. They would be married this spring. In the meantime she was redoing an old house they had bought on Lindenwood. I could not help marveling at the change in her. Connie laughed. “Dallas does that to you,” she said. “I’m a Dallas woman now and I love it.”

I wonder. What did Connie mean when she said she was a Dallas Woman? Obviously it meant for her shedding the shabby hippy life and latching on to a man with a little money and seeming class who had set her up smartly. Well, at least she did not end up a Dallas Cowboy cheerleader. I find myself insisting, however, that she is not The Dallas Woman. Something is amiss. Connie, you are counterfeit.

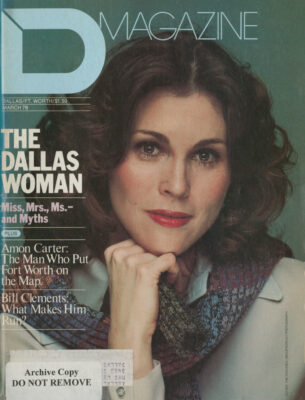

The Dallas Woman

Is there, indeed, a Dallas Woman, or at least a kind of indigenous and unique woman here who stands out from the rest and therefore becomes our symbol of The Dallas Woman? Women are not butterflies to capture and classify under glass. But I will do it anyway. Pin the femme down. Remember in Night of the Iguana when the two women bind the Rev. Shannon to his hammock? The poor sot laments that “there is not a woman in the world who does not take pleasure in-having a man in a tied-up situation.” Tennessee and I agree that turnabout is fair play.

The Dallas Woman is not ubiquitous, not even representative of women everywhere in the city. She is not a democrat. But she embodies that special feminine nuance which is unmistakably Dallas, whether you meet her in some Chinatown or on the Champs-Elysées. You won’t find her in Mesquite but you could run across her in Paris. As Carol Novotny at Neiman’s put it,”’She’s got everything everybody wants: beauty, money and class.”

That’s the high-octane version of The Dallas Woman. There are less expensive, intermediary blends – the graduate students and working girls who go to Europe for edification and adventure, the suburban housewives of middle income who live quiet lives with an occasional indulgence abroad. And after all, the women of Grosse Pointe in Detroit or of River Oaks in Houston have beauty, money and class. And most certainly they are easily distinguished from the Dallas Woman. The Northern woman is stern, mercantile, puritanical, sectarian. The Houston woman is a baubled barbarian. The Dallas Woman is, well, she is Southern: relaxed, aristocratic, artistic, passionate and indulgent. Sure, she is also designing, but it is in pursuit of a feminine ideal rather than raw power. In short she pursues love – ro-romantic love in her youth, maternal love in her middle age and matriarchal love in her old age. The signal characteristic that separates the Dallas Woman and makes her most distinctive and highly appealing to the American male is that she likes men and needs them The new Dallas Woman may support herself and the ERA, but emotionally she is fixed on her man, as he is on her if he has any sense. She dresses and acts to please the male, while pleasing herself. She seeks a combination of freedom and commitment without loss of her femininity. The rest of the givens that go to make up the Dallas Woman are important – beauty. brains and style, professional status or social position/money – but incidental to the mating game which she plays with the highest grace and skill. She is not butch and she is not the submissive Total Woman. She is a contemporary Cleopatra. Which means that she can be a bitch when crossed but an Aphrodite otherwise.

The Matriarch

As far back as I can trace, this sense of a Dallas Woman, this awareness of a duality of femininity and feminism, did not surface until after World War I had obliterated the Victorian Age. There are today in Dallas women who date back to that revolutionary time. A few of them are indeed grandames, the duchesses of the line. I have camouflaged them into a composite we shall call Rose. She is, as much as 1 can make her. true to the spirit of the real progenitors of the Dallas Woman.

Rose could not believe what a disaster the day had been. First, the crush at Nei-man’s. She had not been able to finish her Christmas shopping, and then this blinding sandstorm had blown in from West Texas to put a pall on everything. She was safe and comfortable now, high in her apartment overlooking Turtle Creek, but she was still irritated. Here it was almost dark, the opera would start in two hours, and her friend Irene had begged off accompanying her. She set her jaw and peered through the window.

The city was bathed in eerie yellow light. Armageddon? The first holocaust? Or just bits and pieces of Fort Worth – manure and all – blown in from across the Trinity? Whatever. Rose was not about to let it deter her from hearing Alfredo Kraus sing the role of the Chevalier Des Grieux. In a high, regal voice she summoned the maid. “Lula. bring the telephone.”” If Irene could not drive her she would have a chauffeur. She dialed the limousine service and told them to send a driver. Then she poured herself a glass of sherry. She lit a cigarette. She began calling her friends. Surely someone would want the extra ticket. My God, they were the best seats in the house. But her blandishments fell on deaf ears. The blue-haired dears were up to their double chins and diamonds in atrophy. Rose had been polite on the phone, but she was privately scornful. Here she was, at eighty older than any of them, and not about to be entombed! She was also persistent. She went on to try her daughter, her granddaughter and her great-granddaughter. At last she got an old professor friend who said he would be delighted to meet her at the Music Hall. Dear Lord, she thought, what a chore it is to contribute to the culture. Dallas was going to the dumps, she decided, in more ways than the weather.

It was a far cry from the Dallas Rose had known as a child. She grew up in a great gothic house on Maple near Wolf, a child at play in the last mellowness of the Victorian Age, innocent of what awaited her around the corner of the new century. Her father, a stern gentleman, ruled the house. One evening Rose was dressing in her room, drawing on her stockings with the door open, a slip of a girl in a stew because she was late for the supper table. Her father appeared in the doorway and said icily. “We don’t want to see you until you are fully dressed. Keep the door to your room closed until you are presentable.”

All of a sudden Rose was a woman, too much of a woman. She towered over the boys. But they came calling anyway, the braver ones, because of her beauty and her wit. They came in herds, parking their Model T’s along the street, taking turns sitting on the porch swing with Rose and her girlfriends. It was fun but all very proper. If a boy held your hand he had to marry you; it meant he was in earnest. And of course no beau was acceptable with beer or tobacco on his breath. How quickly that was to change! But unsuspecting Rose and her friends went on living their parents’ dream of a proper upbringing. She was sent away to a smart preparatory school in Virginia.

Summers back in Dallas were charming: Idlewild parties, dancing on the porch at the new Dallas Country Club, swimming at Leachman’s Natatorium in South Dallas. The classiest cadenza to the day was to dress in hats and veils and white gloves and do the drag up Main and down Elm in an open touring car, then hit the Palace drugstore for ice cream sodas.

Rose liked the social whirl in Dallas so much that she did not want to go off to Bryn Mawr. SMU was new. but attracting some of the best families. Why not? Rose’s father consented, grudgingly. At least it would keep her at home where he could keep an eye on her. He had of late detected in Rose something that worried him. Instead of expressing the soft. Southern sensibilities expected of a young lady of her class. Rose seemed to go out of her way to raise eyebrows. She was almost saucy with her boy friends and impudent toward her elders. She insisted on driving cars instead of being driven, and once, while wading in the pond at the country club, she had rolled up her pantalets to expose her knees.

The boys went away to war. Rose was a model of home front decorum. She was sweet and prim and not pushy in class and was a whiz at making bandages for the Red Cross. But when the Armistice was signed and the boys came home Rose and her girlfriends seemed to take leave of their senses. They bobbed their hair, threw off their corsets, lightened and lifted their skirts, put on rouge and lipstick, puffed cigarettes, sipped gin, petted and necked in parked cars and danced the fox trot in what one campus editor disgustedly called a “syncopated embrace.”

Rose had been freed from one convention only to be caught in another, however. She was, in a word, frivolous, indifferent to the serious undertones of her time. It is true that she voted when American women got the franchise in 1920 – she dragged her mother to the polls – but she voted foolishly, as did most of the ladies, for that handsome incompetent Warren G. Harding.

Rose had her head set on a husband. Didn’t every girl? She thought for a heady moment – which lasted for months – that it might be the great white hunter, a blond and dashing safari assistant to Frank (“Bring ’Em Back Alive”) Buck. Both were home town boys who had made it big as circus performers and animal trainers, and now here they were back in Dallas with a truckload of wild beasts for the zoo on Marsalis. Rose met the hunter at a party and instantly they were an item, seen dancing at the Adol-phus, eating at Frank Carraud’s Cafe de Paris. All the boys she had kissed became a blur. He was a man, the first in her life. She would have followed her Caesar to Timbuktu but she never got the chance. One day he left a note and was gone. A real flapper might have bitten her lip and tossed it off to experience. But Rose was really a lady, her heart wounded and her reputation sullied. Mercifully her father took her out of SMU and sent her away to Bryn Mawr.

In time she would return and marry and settle down to being a respectable matron in the new fashionable part of town called Highland Park. She would always be a beauty and a bit sassy, clever on the comeback and, as time wore on, fairly conversant in the arts. Once, in the late Thirties, she met John Gunther as he was researching a book, and when he asked her what she did she replied, “I like to ride horseback. 1 play golf, drink gin, go to parties and dance and send my children to the right schools.”’

After the hunter no man had humiliated her. Her husband was not a conqueror of worlds, but he was a good provider and as constant as sundown and sunrise. Even after he died she continued to indulge herself, developing a passion for the ballet and the theater which took her often to New York and Europe. While she lived well and could never remember a time when she had to worry about money, she lived simply – relatively – and without ostentation. This she drummed into her daughter’s head, this and good manners and the virtue of family and tradition.

Rose’s mouth – once wide and full – has a severe set to it now, formed by the long habit of issuing orders. She is formidable, the queen of Turtle Creek, and one can’t imagine her dancing at the Adolphus in the arms of a great white hunter.

The New Woman

The woman who is known only through

a man is known wrong.

– Henry Adams

The sun also rises on a different Dallas Woman, who is not bound to come home again with a husband, at least not yet. It is the woman mentioned earlier, the one who wants a career and the freedom men enjoy.

When she left college she was sure that she could only make her way as a new woman in San Francisco or Houston. But to her surprise, Dallas had changed. It had cocktail lounges where women could go unescorted; socially and politically things had opened up. A single woman could even get credit, albeit with some effort. But best of all, she found that the city was large enough to give her privacy, that she could live out her new life of independence without intrusion and disapproval. Because she would not count on a husband to support her she became thrifty and money-wise. She learned to use the self-service gasoline pump and to carry jumper cables. She did her own taxes, planned her sojourn abroad, made her own way in the world.

She is not a radical feminist. Now that she has found strength within herself, she finds the notion of vulnerability (female as well as male) quite right in its place. For all the illusions she has shed about a woman’s role she is still a confessed neo-romantic, especially about sex. Without marriage or cohabitation she has found intimacy and an approach to romance that fights the tendency toward posses-siveness and yet maintains commitment.

Remember now that she is under thirty and tends to chart her life confidently. Thus the only complication she foresees is her desire to have children, at least one child. She is bold enough, at the moment, to think that she can pull it off- motherhood at its most responsible – without marriage.

But she won’t. If her career takes off she will put off motherhood, especially under such circumstances. But it is written that she will marry, later than usual, and will have child as well as career, and if not a house in Highland Park then one in East Dallas where lovely old ruins will be resurrected. She will make the best Dallas Woman of them all.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte