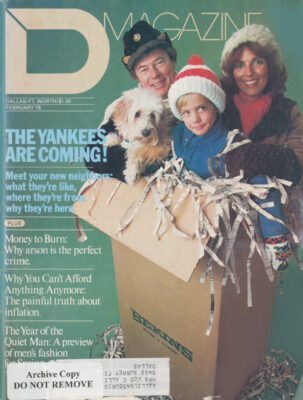

You may have heard all you care to hear about “The Sunbelt.” We all know by now that the U.S. of A. is experiencing an extraordinary population shift, a kind of modern mass migration, from the cold congestion of the North and East to the warm milk and honey of the South and West. And we all know that bright and shiny Dallas sits glistening right smack in the heart of all this burgeoning prosperity-by-sunshine. And we know that our city is bursting with growth and that much of this new populace is composed of native-born American intra-continental immigrants (some call them Yankees).

Yes, we all know all about all that – that Dallas is the big silver buckle in the middle of the Sunbelt, wah-dee-doo-dah. But have we ever stopped to realize what it’s doing to us? To assess how creeping Easternism is changing the complexion of our fair city? How we’re fast becoming an American melting pot? How our Texas blood is running thinner and thinner?

Here are a few statistics to chew on. (Before you bite, note that any statistics regarding “Population” are always something less than scientific fact.) The following estimations represent our collective distillation of studies, surveys, and other sociographic segmentations ranging from the files of the United States Department of Commerce to the files of the Cedar Hill, Texas, water department. Anyway. Did you know that perhaps as few as one out of every five adult Dallasites has lived his whole life in Dallas? That perhaps as many as three out of every five Dallasites have lived here less than ten years? That perhaps one out of every three Dallasites is not even a native Texan? That more people move here from Chicago than from Houston?

Not that any of this is either good or bad. It’s just true. The Yankees are coming. In ever larger numbers. So, in the interest of the new North-South relations, here are some random bits and pieces regarding the Yankee invasion. Like it or not, you’re about to learn yet a little more about our place in the Sunbelt.

The City of Dallas is not a boom-town. The City of Dallas itself, from 1970 to 1977, increased in population by only some 25,000. But “The Greater Dallas Area,” as it was once called, has, in the same seven years, increased in population by over a quarter-million people. There is obviously only one answer to where all those new people are living: In The Suburbs.

Having spent much of my childhood in Richardson, I thought I knew well what Dallas suburbs were all about. First and foremost, they were North. Granted, there were a few sproutings off to the west and east, like Irving and Mesquite. But the real suburban heartland was North: Richardson, Garland, Carrollton/ Farmers Branch. North Central Expressway was the lifeline, Texas Instruments and Collins Radio were the lifeblood, and it was as simple as that.

Until three weeks ago, I didn’t think any differently. Dallas suburbia still meant North. The names had changed – Piano, Addison, and Lewisville were the hot spots now – but suburbia was still eating its way due north, stretching its greedy tentacles as far up as Lake Dallas, McKinney, Rockwall. The southern reaches of Dallas County, as far as I knew, were still populated by little more than cows and Stuckey’s.

Then the news of DeSoto started to hit the local papers. DeSoto, Texas, it was reported, was located in the southern rim of Dallas County. It was described as “one of the fastest growing suburbs in the Dallas area.” DeSoto was making news because it was “beset with local political strife.” And, most intriguing, one of the figures in the political bickering, a DeSoto city councilman, was quoted as blaming DeSoto’s problems on “those transient damn Yankees.”

Aha. “The Yankee Invasion,” in tangible, traumatic, tumultuous form. Here, surely, was a living, vibrant, microcos-mic example of Dallas growth and the impact of the Northeastern migrant influx. Hot stuff.

A bit of research further convinced me that I was on to something significant. DeSoto is one of a cluster of four small cities south of Dallas that are experiencing dramatic growth, with little fanfare. While the spotlight has focused to the north on the population explosion of Piano and the commercial explosion in Ad-dison, the southern cities of DeSoto, Duncanville, Cedar Hill, and Lancaster have been quietly stocking their own ponds. And in surprising numbers. In 1960, the combined population of the four cities was about 15,000. By 1970, it had more than doubled to a population of 34,000. Today, the population has nearly doubled again, and is now in excess of 60,000 people, with at least 5,000 due to move in during the coming year. Duncanville alone is now a city of over 25,000 and has been dubbed “the next Piano.” DeSoto in I960 was a little country burg of 1900 residents; today DeSoto boasts a population of 15,000. And all indications are that this is just the beginning – land development is only now heading into full gear. It is conceivable, and not impossible, that this four-city area may some day be home to half a million people.

It didn’t take much further research to learn that there were two key figures in Desoto, two men who have much to do with the city’s current condition. One was Roy Orr: lifelong DeSoto resident, former DeSoto mayor, currently a Dallas County Commissioner. The other was Durward Davis: a young man, a relative newcomer to DeSoto. and currently mayor of DeSoto. Between them, 1 surmised, I would get the lowdown on this DeSoto business, a first-hand view of the nature of suburban strife, an insiders’ analysis of the “transient damn Yankee” problem. I could already see the headlines: ’The Battle For DeSoto: The South Rises Again to Meet the Onslaught of Yankee Invaders.” I was wrong.

When Roy Orr was growing up in DeSoto in the Thirties and Forties, there wasn’t much to it. DeSoto was little more than an isolated country crossroads, the intersection of Hampton Road and Beltline Road. Where now stand an Exxon, a Shell, and a Gulf, there once stood a general store, a small filling station, and a domino parlor. That was the city of DeSoto. When Roy Orr graduated from high school in 1946 (Lancaster High School – DeSoto didn’t even have one of its own), DeSoto had only some 250 residents, mostly farm people. Dallas was The Big City, far away.

Roy Orr’s home today is only blocks from where he was born. His home now is surrounded with many neighbors. They’re not farm people. They’re city people – white collar, upper-middle class, city people. I want to talk to Roy Orr in his home, in DeSoto. Roy Orr says he would rather talk to me in his Commissioners district office, in Oak Cliff.

The most startling thing about Roy Orr, I notice as he extends his hand and shows me into his office, is that he doesn’t look like his pictures. I had expected a somewhat portly, paunchy figure; instead he is quite lean, hard-lined; his voice is loud, confident, just short of arrogant; his accents and demeanor are country, but not cornball. Some people had told me I wouldn’t like Roy Orr. I wouldn’t like to be his enemy. More than anything he seems tough, belligerent and tough. And frank.

“I know you wanted to talk to me in my home,” he says as I’m sitting down. “But I didn’t want that and I’ll tell you why. I live in a real nice house – not a palace, but real nice. And I had visions of you starting your story by saying ’Roy Orr was sitting in the plush, lush living room of his fabulous mansion in DeSoto . . .’ and I didn’t think that would be fair.” He”s right. I’d had unfair thoughts like that. He’s caught me. I like him.

We have talked for only minutes about the growth and growing pains of DeSoto when Roy Orr blows apart my whole story. Without the provocation of any leading question from me, he suddenly says, “You know, some people are trying to paint this whole DeSoto picture as a Yankees-versus-Rebels thing. Well that’s bull.

“Hell, there’s no such thing. And that’s because there’s no Yankees in DeSoto. Well, of course there are some people who have come from Northern states. But they’re not causing the problems. I’ll tell you what the problem is. It’s just petty, partisan politics. Hell, instead of Yankees against Rebels, it’s just Republicans against Democrats. And I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, there’s just no place for partisanship in city politics.”

Many in DeSoto would cringe to hear such words from Roy Orr. Though he has not technically been involved in DeSoto politics since he resigned the mayorship in 1972 to become Commissioner, Orr has often been accused of pulling political strings in the city with back-room, behind-the-scenes influence. Orr’s stature and political influence in the DeSoto community are undeniable; the extent to which he exerts that influence and the level of its benefit to the community is a matter of question. The answer depends on whom in DeSoto you ask. Orr is the first to admit it.

“People either hate me or they love me,” he declares. “And that’s the way I like it. But I’ ve often said that while there may be people who love DeSoto as much as I do, there’s nobody who loves it more than I do. I don’t want to get involved because I don’t want DeSoto to be a partisan political town. But if I was involved, you’d damn well know it. I don’t need anyone else to carry my water.”

It’s doubtful that Roy Orr really believes for a minute that he is not a significant force in DeSoto politics. But his stance is unequivocal because he is a consummate politician, a politician of the traditional, small-town-Texas ilk. His “constituency” in DeSoto, most would tell you, lies in the longer term residents, those who have known DeSoto more as a small town than as a growing city suburb. Orr is fully aware of the changes.

“1 can tell you what has created the political tensions in DeSoto. First, I bet you that 90 percent of the new growth in DeSoto has been people moving here from South Oak Cliff- and I don’t have to go into the details why. . . [I guess white flight and he does not deny it]. Now that’s only a move of 8 or 10 miles, but it makes a big difference. In Oak Cliff, these were people who were part of the big city situation. Active involvement in politics wasn’t something that occurred to them. When they move to little old DeSoto, everything gets magnified. Politics are suddenly more accessible. They almost automatically become more involved. You’ve heard the old expression about those who ’can’t stand the prosperity;’ well, in this case, they ’can’t stand the authority.’ Suddenly, they’re instant experts. Ninety-day wonders. I think the problems in DeSoto can be traced directly to three or four newcomer troublemakers who let politics go to their heads.

Roy Orr leans back in his chair and pulls up his legs into the chair in a cross-legged position that is odd, but obviously comfortable to him. It’s an almost childlike pose, and lends a curious contrast to his reputation as political ogre – ogre,at least to those in DeSoto who oppose him. The complaint is that Orr has too long been at the controls of a “one-man political machine,” a machine out of sync with the new DeSoto. He has been pegged as a kind of anachronistic town boss.

Orr cringes visibly at the “town boss” tag. “Don’t ever say that,” he retorts. “It’s just another one of those labels that a few people around here have tried to create. Look, I’m just a fighter. Whether it’s politics or checkers, I’ll try to beat you as bad as I can beat you. Some people don’t like that. Now you take Mayor Davis. ’Cause I know you’ll be talking to him. Now he’ll be real low-key, real compassionate, real smooth. But when his lips move. . .” His tone is heated now. There is obviously no love lost between former mayor Roy Orr and current mayor Durward Davis. “It’s hard to compete against hypocrites,” says Orr. “Because I’m not a hypocrite.”

It’s not difficult to see why Roy Orr rubs some people the wrong way. The “country fighter” knows no moderation in style. But that same frankness is also his saving grace. As I leave, he warns me again, “Don’t you fall for that Yankee business. You’re on the wrong track. We don’t have any problem with Yankees in DeSoto. Besides,” he winks, ’”some of my best friends are Yankees.”

Interstate Highway 35 South to DeSoto is almost deserted at 2 in the afternoon. They say that even at rush hour, traffic moves along at a reasonable clip. Once you’re past Oak Cliff, everything seems to end. It seems impossible that there can be thriving suburbs out here. It’s only about 10 miles from downtown Dallas to the DeSoto turnoff at Beltline Road. Heading west on Beltline, one can easily understand the appeal of this area – the rolling hills, decked profusely with cedar trees, provide terrain as interesting and attractive as any in Dallas County. At the top of one of these hills, Hampton Road crosses Beltline. A big silver water tower, boasting typical “Srs. 75” graffiti, marks this as the center of DeSoto.

For some reason, on this, my first visit to DeSoto, I am expecting to see remnants of a small Texas town. A little wooden-frame corner grocery, maybe. An old abandoned movie house, perhaps. Nothing of the sort. Except for an unused fresh produce stand on one corner, this intersection is ringed with gas stations and churches. Near the southwest corner is the modern white municipal building, my destination. As I arrive at the front door, a rather pudgy young man in brown slacks and a striped knit shirt is also just arriving. “Hi,” he greets me with a big warm smile, pegging me immediately as his interviewer. “I’m Durward Davis.”

Before we even take a step inside, the mayor suggests that instead we get in the car and take a drive around DeSoto. We climb into a borrowed Chevrolet station wagon (his new Corvette, he explains, is in the shop) and set out.

From the first, it is clear that Durward Davis has enormous pride in his city. His adopted city. Davis grew up in South Oak Cliff, graduated from South Oak Cliff High School, before moving to DeSoto in 1970. The mayorship of DeSoto is a new job for him, and only a part-time job at that. Professionally, the mayor of DeSoto is a laundryman, owner of the One-Hour Martinizing shop. Davis became mayor of DeSoto last year after a hard-fought, increasingly bitter campaign against incumbent mayor Charles Harwell, a long-time friend and political ally of Roy Orr. His victory was considered an upset.

But he seems very comfortable in his new role. He is, as one might expect the mayor of a fast-growing suburb to be, an excellent P.R. man. Our tour begins in a residential housing subdivision. That’s because there is little else in DeSoto except residential housing subdivisions. Except for the Hampton Road commercial strip (Gibson’s, Safeway, Jack-In-The-Box, etc.), DeSoto is a residential housing subdivision. It is as pure and absolute a bedroom community as a suburb can be.

Durward Davis is an expert in the field of residential housing subdivisions. As we drive, he offers running commentary regarding styles, trends, building periods. “Now you’ll notice here that there are two different styles on either side of this street. The homes on the left are from a slightly earlier development period than those on the right, all of which are, of course, of pier point beam construction.” (Of course? Even as a child of suburbia, I can discern no distinguishing characteristics in any of these homes. Only that some have basketball hoops over the garage and some don’t.) The tour winds through a seemingly endless series of housing developments: North Meadows, South Meadows, High Meadows, Hampton Place Estates, South Hampton Estates, Mantlebrook, Meadowbrook, Meadowbook Two, Meadowbrook Three, “and the land you see over there will be Meadowbrook Four, Five, and Six.” Everywhere there is new construction. Mayor Davis scans the streets as intently as I do, noting the name of each builder, each realtor, taking in the size and design of each new house. “Now you’ll notice in this area the designs are a little more modern, a little different from the others. Now they won’t be as modern as, say. Piano, but then this is a conservative community and the houses reflect that. Look, see there. A two-story going up. Great. I like those. “

His enthusiasm is real. He is a true appreciator of the art of suburban housing. He has driven all over Dallas County studying various developments, taking notes, bringing his discoveries back to DeSoto. He is particularly proud of one new subdivision, just about to sprout, which incorporates one of his suggestions and will feature “50-foot setback.” It’s a strange passion, but one that seems beautifully suited to a mayor of DeSoto.

At one point, the Mayor swings the station wagon down an alley, onto a bumpy dirt road, across a field, and into a wooded area. Here he presents me with my first of several views of the pride and joy of DeSoto: Ten-Mile Creek. Davis describes it as “the most aesthetically beautiful in Dallas County, according to the Sierra Club.” It is indeed impressive, winding its way serenely through DeSo-to, flanked by white cliffs and potential real estate goldmines. The tour ultimately follows the creek to the northwestern outskirts of DeSoto to a particularly deep and tranquil section of the creek. I suspect the mayor has spent much time here, seeking relief from the DeSoto political wars.

“I decided to run for mayor,” he reflects, “because I didn’t go for the old back room crony politics that ran this city. 1 didn’t think it was good for the community. I had no political experience – I’m only 27 – and I didn’t really know what I was getting in for. I’ve never seen so much mud-slinging in my life. It was sickening – dirty, small-town, petty politics. But, you know, you have to play the game. When you live in Roy Orr’s town, you have to play Roy Orr’s game. Either you beat him, or he beats you.”

As we return to town through yet another subdivision, Davis points out a large white-brick plantation-style house with white columns and a fountain in the front yard. “That’s Roy Orr’s house,” says Davis, shaking his head – less, it seems, at the incongruous ostentation of the house than at the man inside. “Roy and I are simply on different sides of the fence. I just wish he’d leave me alone. I just wish he’d leave my city alone.”

Whether DeSoto is Durward Davis’ city or Roy Orr’s city is still in question as the political tug of war continues. And really, Orrand Davis are just figureheads in a suburban condition. But, driving back to the municipal building and noting the brand new high school, the post office building that looks like new, the police and fire station that looks like new, and all those new, new houses, one gets the sense that the odds are stacking in Davis’ favor. This is a new city. Roy Orr’s little old DeSoto has been buried under a flurry of concrete and brick. As Davis explains it, “DeSoto is getting younger and younger. Even now the average age is 27. This is a hard core upper-middle-class community. It has one of the highest average per capita income levels in Dallas County, second only, I’ve been told, to Highland Park. It’s high because there is almost no low income group in DeSoto. Everyone in this town makes $25,000 a year. It’s almost entirely a college-educated, white-collar community with high professional ambition. These people, and all the new people that are going to follow, just won’t accept the old smalltown political ways. DeSoto was Roy Orr’s beginning, but if he’s not careful, if he can’t adjust, it may also be his end.”

Such talk, by both men, seems unnecessarily heated to a reporter who was just looking for a simple Yankee problem. But interestingly enough, DeSoto may be only the testing ground for the political battles between these two distinctive rivals. There is talk (some say serious, Davis says no) that Davis will be persuaded to oppose Orr for his District 4 County Commissioner’s seat in the May elections. If so, DeSoto’s growing pains will become a little more painful.

Driving out of peaceful and prosperous DeSoto on this crystal clear sunny afternoon. I can only note that it certainly doesn’t look like a city in turmoil. In spite of the city council flaps, the petition recalls, and the zoning fights, this is still basically a contented community where mothers raise plants, fathers come home for supper, and children get taller. In spite of their differences, Roy Orr and Durward Davis both said, in almost identical words, “’DeSoto is my home. I just want a nice place to raise my family.”

DeSoto is simply going though what Piano went through a few years ago, and Richardson before that. Before long, DeSoto will blossom into yet another of Dallas’ many satellite cities. As Mayor Davis puts it. “Our future is assured, if nothing else, by the miserable state of North Central Expressway. We are an accessible alternative to the suburbs to the north.” DeSoto and the New Southern Suburbs are doing fine, thank you. The South is rising again. Even with Yankees.

So This Is Dallas: A few First Impressions

Jim Ryan, Forward, Dallas Tornado Soccer Club.

Born and raised in Scotland

This is the first time I’ve seen professional football. At first, I didn’t think there was much to it – just the biggest guys in America knocking lumps in one another. But I’m starting to understand it and it’s just tremendous. The Cowboys seem like gods here, they have such status in the community. The whole thing is real big time, real professional. I miss the English sports, though, the cricket and rugby, although Channel 13 does a great job with soccer. And I have a short wave radio, so I can still tune in the BBC news and the Saturday night soccer results.

Steve Daniels, Associate Professor of English, SMU

Born and raised in Brooklyn

I’m trying to figure out if I have any impressions of Dallas. I don’t guess I’ve ever really made the move. Dallas is an easy place to live in without being committed. Well, there is one thing. On my first or second day here, some friends took me out to NorthPark. I was very impressed, but something made me uneasy. I couldn’t figure out what it was. Finally, I realized it was how clean and neat the people were. I’m still impressed by that.

Susan Mead, Director, Historic Preservation League

Born and raised in Dallas

I left in 1966 to attend school in Hartford and Boston. Eight years later I came back for a visit and just got swept up. Dallas is a much more vital, more stimulating place than it used to be. I have a sort of saying: Every renaissance needs a healthy economy. That’s why I’m here now – we have the means to support the arts, to create. And there’s no doubt but that Dallas will look to its past and start doing something with it.

Erika Sanchez, Director, Office of News and Information, University of Dallas

Born and raised in New York City

It was hard to get used to North Dallas. I felt very isolated. I remember looking out my window and seeing no one. I went to the park almost every afternoon and I never saw anybody … it was like a moonscape. Now I realize everyone was in their backyard or at the neighbor’s pool.

Camille Cates, Assistant to the City Manager

Raised in Killeen, Brenham and El Paso, Texas

When I meet people here, they frequently ask me where I live before they ask what I do. Well, nobody ever asked me where I lived when I was working in California. And the reason for that was that it didn’t make much difference. But it’s clear that in Dallas, where you live really says something about you. Swiss Avenue and Richardson are light years apart.

– Lindsay Heinsen

The Chicago Connection

The six-county Chicago metropolitan area, stretching north to Wisconsin, west to the Fox River Valley and south almost to Peoria, is something of a fertile crescent for SMU. For a couple of decades now, Illinois has consistently sent more students to SMU than any other state except Texas. In 1977-78. for example, Illinois can claim 463 students out of a total enrollment of 9000 – not overwhelming, perhaps, but close to double the number from the third-ranking state (Missouri), and more than double the number from the fourth (Oklahoma).

Most of these southbound Illini, it turns out. come from the Northern and Western suburbs of the Windy City – especially from wealthy, powerhouse high schools like Lyons Township. Glenbards West, South and North, Hinsdale, New Triers East and West, and Lake Forest.

If anyone deserves credit for forging the Chicago connection, it is probably the late Leonard Nystrom, who came to SMU just after World War II. Nystrom’s biannual driving tours through the mid-south, midwest and Great Plains states were the first systematic out-of-state recruiting efforts by the university, and Chicago was a high point on his itinerary.

“Nystrom had done his undergrad work at Northwestern,” says Frank Ivey, executive director of the alumni association and Nystrom’s former colleague. “He knew the potential of the area. But I’d say it was in the late Fifties and early Sixties that our concentrated efforts really began. We made sure we visited a wide variety of schools in the Chicago area, and we cultivated it with an annual high school counsellors’ conference. After that, it’s not terribly complicated. A few students came down, had a good experience at SMU and told their friends about it. It’s snowballed from there.”

Most of the Chicagoans who come to SMU, Ivey finds, start off looking for a middle-sized, private university with a good (if not too good) academic reputation. Often, they like the idea of escaping those hard winters on the lakeshore, too. Over the years, SMU’s stiffest competition has come from Duke, Van-derbilt. Northwestern, Tulane, Rice and Trinity. What tips the balance? “Frankly, we’re a bargain compared to all but the last two,” says Ivey.

So, Dallas, say hello to the 70 Chi-cagoans in SMU’s freshman class – and hello to a new group of prospective neighbors. They may not know it yet, but if history repeats itself with the class of ’81, most of them will make their homes here after graduation.

– Lindsay Heinsen

The New Carpetbaggers

Nobody’s pulling any punches: Most newcomers frankly admit they came to Dallas in search of economic opportunity. Getting in on the ground floor, you know. Nothing like it to make people pack up and move around. Of course, not everyone actually finds the pot of gold at the end of Central Expressway. But some do – enough to spread the word a little further, and make Dallas money seem to shine a little brighter. So we thought we’d join the Chamber of Commerce and the North Texas Commission in a little low-key myth-making of our own.

If you skim the September 1977 issue of Scientific American, you’ll understand “metal oxide semiconductor technology” as well as we do. All we know is that the words add up to MOSTEK, and that nuances of microelectronics technology aside, MOSTEK is one of the hottest stars in Dallas’ generally star-studded electronics industry.

MOSTEK board chairman L. J. Sevin came to Dallas in 1958 from Louisiana State University, to take a job at Texas Instruments. After about a decade, Sevin and several other ex-T.I. employees went on to found the new venture, an independent supplier of integrated circuits and complete systems to the growing computer industry. Among their most successful products: the largest-capacity random-access memory chip currently available, and computers whose central processing units are the size of a child’s thumbnail. A cupful of MOSTEK’s memory chips sells for $30,000. The company’s total sales have reached $85 million annually, with a yearly growth rate of 35 to 40 percent. Its success is especially impressive in light of tremendous competition in the microelectronics industry, where technical innovations lower manufacturing costs (and prices) almost monthly.

Unlike many of Dallas’ newcomer/entrepreneurs, Sevin did not move to Dallas specifically to found his personal empire. But he’s mighty glad that MOSTEK is here now, instead of in “Silicon Valley” – Santa Clara County, Cali-fornia – where America’s high technology industry is concentrated. Entrepreneurs there face tough state regulation and some of the highest rents in the country.

While Dallas is a safe haven for MOSTEK. and others in the well-established electronics industry, it can also be fairly hostile territory for unfamiliar ideas. A case in point: the bagel. As late as last year, the chances of a new bagelry lasting six months seemed pretty dismal. But thanks to another pair of entrepreneurs, Larry and Sue Goldstein of Detroit, not only bagels but the bagel brunch and bagel thins are on their way to becoming new Dallas commonplace

Although owners of a full-service restaurant in Detroit, Larry and Sue were looking around for new challenges – and getting pretty sick of northern winters. “My work day” starts very early. I have to get up at 4 a.m. And I just hated to get out of the shower feeling really good, and then face scraping ice off the car in the dark.”

After an apprenticeship at a friend’s deli in Toledo, Larry and his wife moved to Dallas in l977. Theirchosen location: a failed bagel factory/delicatessen on Spring Valley Road whose former owners returned to New York after their abrasive style drove off the customers. Banks were reluctant to finance the venture, so Larry and Sue got started with the help of friends and proceeds from the sale of their Detroit restaurant.

Although Larry has helped open a total of four restaurants in Detroit and Toledo, none has hit the black as quickly as their bagel fiefdom on Spring Valley. Today, they carry on five operations – wholesale and retail bagel sales, deli sales, a sandwich service and catering arm. Meanwhile, Bagelstein’s Sunday brunch (featuring free coffee and bagel thins) is fast becoming a Richardson institution.

– Wade Leftwich

Have Yankees Made the Difference at the Herald?

You needn’t read the logos to tell them apart; one glance at the typeface is sufficient. “Old English” for the Dallas Morning News, “Avant Garde” for the Dallas Times Herald. In short, the News represents Old Dallas, the Herald the Immigrant Wave.

The difference is more than typographical, of course. The top 12 editorial positions at the News are occupied by people who built their careers there; their average tenure is 22 years. At the Herald, few editors have been on the job more than five years; the average is only three.

The winds of change began to blow through Herald Square three years ago when Tom Johnson, brought in to head the Times Mirror Corporation’s new acquisition, hired Ken Johnson from the Washington Post as executive editor and Will Jarrett from the Philadelphia Inquirer as managing editor. The next two years saw the arrival of assistant managing editors Larry Jolidan from the Detroit Free Press and Tim Kelly from the Philadelphia Inquirer, executive sports editor Larry Tarlton from Charlotte, N.C., feature editor Sue Smith from the Chicago Tribune, and metropolitan editor Rone Tempest from the Detroit Free Press.

But the Herald is not run entirely by Yankees. In addition to veterans like Vivian Castleberry and Blackie Sherrod, many of the newcomers have Texas, or at least Southwestern, backgrounds. Jarrett, for example, grew up in Odessa, Smith in Lockhart.

Predictably, Ken Johnson argues that the concentration of aggressive, competitive newcomers at the Herald makes for a fresh approach to local news. The most obvious example is the Herald’s coverage of the Commissioners’ Court boondoggle, which arose because Johnson was struck by the illogic of apportioning county road funds equally among the commissioners. Oldtimers accepted the anomaly out of familiarity. It took a newcomer’s eye, Herald people assert, to see it as potentially newsworthy.

The News wouldn’t agree. The grandson of its founder is publisher, and two great-grandsons work for the paper. Executive editor Tom Simmons has been at the News since the Great Depression. Managing editor Terry Walsh has been there over 30 years, and assistant managing editors Buster Haas and Robert Miller are close behind at 25 each. The company’s practice is to promote within the ranks rather than to hire editors from outside.

While rising through the ranks provides job security and ensures instant familiarity on the part of the News’ staff with the city they are covering, some reporters feel that it also creates a hidebound adherence to tradition for tradition’s sake. Writers complain of the “no jump” rule, which keeps front page stories from being continued elsewhere, making the paper easier to read at the breakfast table or on the bus. Reporter Mary Elson, who moved from the News to the Herald, claims “It’s very hard to be much of a writer there, at least on city news stories, because there is so much emphasis on getting the story the right length, rather than getting it right.”

Still, the Herald can’t compare to the News for knowledge of (and an important place in) local history. The roots of the News are as deep as roots go in Texas, and the paper’s claim to being the state’s oldest business institution goes unchallenged. But in a city being populated by newcomers, will the power of the institution continue to be strong enough to withstand a determined onslaught by the Herald?

– Wade Leftwich

North Is North, and South Is South…

All in all, we think both sides have been downright sporting in this latest cultural confrontation between North and South. If nothing else, our manners have improved in the past century or so. So much so, in fact, that we’re getting a little worried. Civility is one thing. Inbreeding is quite another.

We think it’s all well and good that some sort of olive branch has been passed across the Mason-Dixon line. After all, neither North nor South could ever lay much claim to cultural superiority anyway.

So we have reached a tenuous détente: I won’t laugh at your stocking cap, if you won’t laugh at my white belt. That sort of thing. But let’s not let this get out of hand. Cold war is still war. Face it: Yankees still bug the hell out of Texans and vice versa.

What follows is a brief reminder that North is North, and South is South, and never the twain shall meet. In no particular order, you will find our Northern imrnigrants’ favorite gripes about Tex-ans, and homefolks’ pet peeves about Yankees. If you find nothing in either column amusing or even mildly interesting, you might want to brush up on your regional integrity. It could be that you’ve unwittingly become a cultural half-breed. Which may be okay for you, but how are you going to explain it to your children?

What Texans dislike about Yankees.

1. Gripes about the local newspapers.

Sure, the New York Times is wonderful. No, the Morning News is no Washington Post. We know, we know. Enough.

2. Wearing hiking boots with cutoffs in the summer. That may look swell in Wisconsin, but. . . no, not even in Wisconsin.

3. Badmouthing Dr Pepper. It does not taste like prune juice.

4. “Rubbers.” Can’t they just call them galoshes? Or even boots? It would be a lot less confusing.

5. Asking for “Jimmies” on ice cream cones. Face it. They look like insect droppings.

6. Pudding.

7. “Trousers.” Any good American knows that pants are pants. And they’re not ’”dungarees,” either.8. Down-filled ski parkas. If God had wanted us to wear sleeping bags, we would have been born asleep.

9. Peanut butter and bacon sandwiches. Taste begins with what you eat.

10. “Soda.” Soda is what you mix with Scotch. If you want a soft drink, say so.

11. Calling a hamburger a “hamburg sandwich.” Come on. A sandwich is two pieces of bread with meat and other stuff between them. A hamburger is. . .a hamburger.

12. Wearing shirt collars inside crewneck sweaters. Is there something neat about looking like a priest?

13. “Bring” versus “take.” Okay. Once and for all. You do not bring your clothes to the cleaners. You take them. After all, you don’t hear anyone saying “I’m gonna bring a nap,” do you?

What Yankees dislike about Texans.

1. Driving 15 miles per hour after aquarter-inch snowfall. It would be funny if it weren’t so dangerous.

2. Refusal to jaywalk. If the light at thecorner said “Don’t Breathe” you’d probably obey that too.

3. Mexican food discussions. The onlyquestion worth resolving is why doesanybody eat the stuff in the first place?

4. Men who open their car doors atstop lights and spit.

5. Catfish. Whence comes the Texasmyth that this is seafood?

6. Insistence on getting in long carlines. At toll booths, in traffic tie-ups, atparking lot gates. In the north, peopledo their utmost to slip past lines; herepeople make an effort to join them.

7. No respect for lamb. Man does notlive by beef alone.

8. Bourbon.

9. Abuse of the preposition “at.” Example: “Where’s Roy at?”

10. Short-sleeved shirts under sport coats. Especially on guys with hairy wrists.

11. Courteous sports fans. You’d think that Boo was a four-letter word.

12. Cream gravy. Worse than tasteless, it’s pointless.

13. “Fixin’ to.” “I’m fixin’ to go into the kitchen.” Okay. Will you be goin some mashed potatoes?

– David Bauer and Jim Atkinson

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte