Along with the pure pleasure of imagination and design, the joy of creation as expressed in form, color, line and motion (implied or stated) is what Calder’s Universe is all about. The fine retrospective show of Alexander Calder’s work opening at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts on September 14 was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and sponsored by Champion International Corporation. It includes some 200 works by this prolific 20th-century American artist (1898-1976). The works have been grouped into 17 categories, largely on the basis of medium, and range from wire circus figures only inches high to metal stabiles (stationary objects) soaring several feet into the air; from drawings and gouaches to jewelry and household objects; and from the truly creative to the self-imitative. Permeating the whole range of objects and media are the energy, humor and versatility of the artist.

Calder’s work throws many of us off balance by challenging our notion that art must be solemn to be good. Then it adds deceptive simplicity, images that look like a child’s visualization of a grownup object. And often it is made out of bits and pieces of found objects – glass, rubber tubing and tin cans – an art of discovery, in which fragments are given meaning. The circus figures, such as the bright orange cloth-and-wire lion in a brightly painted wooden cage, are disarmingly simple, playful and witty. The jewelry and household gadgets are also filled with humor and parody, like The Jealous Husband (c. 1940), a brass necklace that resembles a chastity belt. The humor of Calder’s work deceives the viewer – one is tempted to see the artist as a toymaker, a gadget and gimmick fashioner (as in the coffee cup holders that sit on metal coils to keep them from spilling when put down on a table) who appeals to the child in each of us. But his is a calculated simplicity, which carefully balances forms and colors, creates tension or rhythmic flow, and is always aware of the importance of movement and structure. At his best, Calder is able to create strong, forceful images; at his worst, he is a fine technician producing decorative objects that are imaginatively conceived and pleasing to the eye. Calder delights in images that are at once playful and serious, that elicit laughter but implore us to look deeper for the structure beneath.

The DMFA exhibition includes a sample of Calder’s work before he went to Paris-where his artistic flowering took place-in 1926, including his Zoo drawings, illustrations from Animal Sketching, andhis oil of The Flying Trapeze (c. 1925). Allreflect Calder’s constant partiality foranimal and circus motifs. In Paris, Caldercontinued making toys and began producing the now famous wood and wireanimals that culminated in his completed Calder progressed to mechanized sculptures before settling in the early Thirties on his most innovative creation, the mobile (named by Marcel Duchamp, the leading Dadaist).

Besides serving to establish his reputation, the Paris years were very important for Calder’s formulation of his developing style. There he was exposed to the newest movements and the works of the avant-garde artists of the day. Two of these, Piet Mondrian and Joan Miró, made a lasting impact on Calder. To Mondrian’s palette (black and the primary colors) and Mirós shapes, Calder added the Con-structivist theories of movement in space and construction with machine materials and the playfulness of the Dadaist. The result was his moving sculptures. Calder’s interest in abstraction can also be traced to Mondrian, as well as to Leger. Abstraction of forms appears not only in Calder’s wire sculptures, such as Universe (1931), but in drawings such as In Perspective (c. 1930), where line replaces wire as the creating medium, often losing energy and vitality when transferred to paper.

The DMFA exhibition includes the artist’s work in oils and gouaches, the latter being more interesting and more dynamic. At times both have a hard, static quality, their two dimensions constricting Calder’s lyrical style. The gouaches, begun after dissatisfaction with the oil medium, can be exciting, imbued with the familiar Calder forms and red, blue, black, yellow and white palette. Often the gouaches degenerate into self-imitations by the artist, whose repetitious use of forms fails to achieve the spontaneity and movement of his more successful productions (Big Bug and Yellow Equestrienne are examples of this). A similar repetitiveness characterizes some of his prints and posters, such as The Red Nose, and works such as his decorated Braniff airplanes, Flying Colors and Flying Colors of the United States, which border on pure gimmickry. Calder’s facility leads him at times to produce pure decoration in works that lack the imagination, composition, or precision of his mobiles and stabiles. His tapestries (such as Spiral) and wallpapers often fall into this category. They are bright, pleasing to the eye, carefully crafted, but by and large dry and uninspired, lacking the breath of creativity that infuses Calder’s more personal creations.

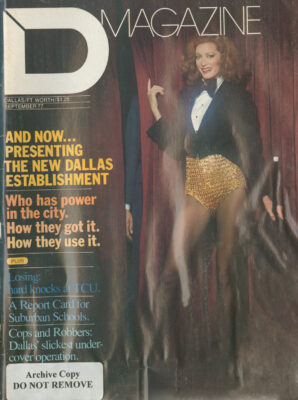

Of particular sensitivity are the household objects in this show, private creations designed for the use of the artist or his friends, never intended to be displayed as art objects divorced from their environGrand Design: Calder’s versatility is shown in everything from gouaches and sculptures to jewelry such as this leather and brass necklace created about 1926.

ment. Yet they manage to stand on their own as reminders of Calder’s insistent whimsy in his attempt to remake the universe around him. The ladles, coffee cups and forks reveal the artist’s constant preoccupation with technology, which he humanizes and parodies. Calder’s jewelry, too, is highly personal, made of wire, metal, and often with bits of found or discarded objects.

Calder’s contribution to 20th-century art and the basis for lasting recognition of his work rests on his mobiles, in which form, color and movement are juxtaposed and carefully balanced into harmonious wholes. Each part is a necessary counterpoint and space and patterns created by movement replace the mass as the dynamic force. Shadow and chance movement become energetic elements of design. “When everything goes right,” Calder said, “a mobile is a piece of poetry that dances with the joy of life and surprises.” Calder once explained that he created mobiles because he “felt that art was too static to reflect our world of movement.’’

Calder’s mobiles evolved from works that incorporated wire and bits of colored glass, ceramic or wood, such as Mobile (1933), Little Face (c. 1945), and Fish (1948-50), to mobiles of metal, painted in Calder’s distinctive colors, such as Indian Feathers (1969). His later mobiles, made of steel, more complex in their spatial relationships and patterns of movement and larger in scale, culminate in the late Fifties and after with his monumental mobiles for public and corporate spaces (such as .125 for Kennedy Airport, Eléments Démontables for a Wichita bank, and Universe, a mechanized mobile, for the Sears Tower in Chicago). But his smaller mobiles have a distinctive dynamism that is not dependent on size, such as Little Spider (c. 1940) and Five Red Arcs (1948). Wit and whimsy pervade his mobiles too, as in Performing Seal(c. 1950) and Chagall Mobile (1944), the latter a work that parodies and plays with forms reminiscent of Chagall’s flying figures and cows.

Calder fuses dynamic movement, humanized technology and imaginative forms in his “stabiles” of sheet metal, which he began producing in the Thirties. Morning Cobweb (1945) and The Crab (1962) are strong sculptural forms which, while stationary, are infused with implicit energy. The mocking quality of Calder is suited for such works as Longnose (1957), a stabile that looks like both dinosaur and bird, simultaneously prehistoric and futuristic. In the early Sixties, with the increasing public and corporate commissions of his works, Calder’s stabiles become icons of monumental size, partly in response to the vastness and scale of the urban environment in which they were to be placed. Calder creatures began appearing around the country and abroad (Teodelapio in Spoleto, Italy; La Grande Vitesse in Grand Rapids, Michigan; and Flamingo in Chicago) combining the playful, whimsical figures he once did in wire with a vitality that both parodies and humanizes the urban landscape.

The DMFA show, while emphasizing the range of Calder’s artistic endeavors, also poses questions common to 20th-century art. The general problem with Calder is the one inherent in judging contemporary art, especially that of a prolific and versatile artist who has worked in so many media and who has completely captured the popular imagination. Like Picasso’s and Chagall’s, Calder’s work is uneven, making it difficult to distinguish (especially in a large retrospective) the major from the minor works, the creative from the self-imitative. Where does art become artifice and where does imagination become gimmick? Calder makes the answer difficult because he delights in play and parody. He is the ringmaster of his universe, manipulating forms and asserting his presence much in the way he did with wire figures when he gave performances of The Circus. His magic is based partly on his humanity – he transforms the technological into the imaginative, he takes the trivial and makes it funny or beautiful, and, fulfilling his life ambition, he “makes things that are fun to look at.” Producing pleasing objects may be a fine humanitarian goal, but it isn’t enough to warrant lasting artistic recognition. Versatility is not synonymous with quality.

The DMFA show provides a basis for beginning to put Calder into perspective. His greatest talents lie in his stabiles and mobiles. In his preface to a catalogue for a Paris exhibition in 1946, Jean-Paul Sartre summed up the magic of the mobiles: “A mobile does not suggest anything: it captures genuine living movements and shapes them. Mobiles have no meaning, make you think of nothing but themselves. They are, that is all; they are absolutes … In short, although mobiles do not seek to imitate anything . . . they are nevertheless at once lyrical inventions, technical combinations of an almost mathematical quality and sensitive symbols of Nature.” Not a bad invention fora “window dresser of space,” Calder’s own assessment of his role.

Related Articles

Restaurant Openings and Closings

Try the Whole Roast Pig at This Mexico City-Inspired New Taco Spot

Its founders may have a fine-dining pedigree working for Julian Barsotti, but Tacos El Metro is a casual spot with tacos, tortas, and killer beans.

Visual Arts

Raychael Stine’s Technicolor Return to Dallas

The painter's exhibition at Cris Worley Fine Arts is a reflection of her training at UTD—and of Dallas' golden period of art.

By Richard Patterson

Dallas History

Tales from the Dallas History Archives: Scenes from 1949, When the Mob Ruled Dallas

In 1949, streetcars still roamed Dallas' streets, the Adolphus Hotel towered over its neighbors downtown, the State Fair was still segregated, and Benny Binion wanted his money.