The French bided their time in promoting the Caribbean island of Martinique as a vacationland, and their wait has paid off handsomely. Since 1972. good roads have replaced rutted, unpaved lanes. Unskilled islanders were trained for work in hotels before they were built. A few excellent hotels were opened, and then the government clamped down on the 200-room-plus category. It was decided that old plantation houses and mansions with interesting histories should be recycled as guest houses. Laws to avoid crass commercialism – a curse at many Caribbean destinations – were put through to keep Martinique’s agrarian economy in sensible balance with the tourist business.

As a consequence, visitors find a peaceable way of life in Martinique. Sugar cane and pineapples and bananas grow luxuriantly in the rolling loamy hills. People are at ease with their work. Vacation niceties are well thought out. Poinsettias blaze along mountain roads. Locals invite visitors to their cockfights in raftered barn arenas. Stunning scenic vistas plunging down to wide sand beaches are as pristine as they were when Marie Josephine de la Pagerie, of a rich French Martinique plantation family, married Napoleon I and became Empress of France.

Until a few years ago, about a dozen French “Creole White” families owned most of Martinique, living in plantation manor houses as resplendent as any in our antebellum South. Their children went to school in France, and on my visits, I could discern few differences between their manners and attitudes and those of the French rural aristocracy in the Loire Valley. That’s changed. Many of the grand old plantations have been sold to corporate farm operators. But several of the island’s businesses are owned by scions of the plantation class. Roger Albert is one, whose duty free shops and tour company are among the first things you see around La Savane, the main square on the harbor in Martinique’s capital city, Fort-de-France.

Fort-de-France’s harbor is a favorite rendezvous for yachters. Large cruise ships anchor farther offshore in deep waters, their tenders plying the harbor with loads of passengers setting out to shop or to sample the French and Creole cooking in a dozen fine bistros and restaurants. Except for the predominantly black population, the atmosphere vaguely resembles the French Riviera, the back streets of Cannes or Nice. La Savane is the city’s focal point, but there’s so much more.

Dark alleys wind up steps into the surrounding hills. Buildings are pastel, French provincial a la Dior, who must have found his modish fabric inspirations in French villages. Overhanging balconies are replete with potted flowers, the hybrid architecture a cross between French mainland styles and semitropical openness.

Mont Pelée towers over the island’s 1100 square miles at 4,592 feet. In 1902, Pelée exploded, a volcano gone berserk. The eruption wiped out Saint-Pierre, a city of 30,000, in three minutes. Only one man survived – in jail. Capitalizing on his good fortune, he joined the Barnum & Bailey circus. A two-room modern museum in Saint-Pierre details the holocaust in photos, sketches, and the meager leftovers unearthed in the reborn cobbled mountain town, which had been called “The Paris of the New World.” A singular testament is the Christ figure, from a crucifix found in cathedral rubble; parts of the figure are missing, but it has the power of Greek sculpture, unwhole, intensely moving.

The first beachhead toward wider tourism to Martinique a few years back was the opening of Club Mediterranée at Sainte-Anne on the island’s southern extremity. A $41/2-million extravagance, it’s a private, self-contained village called Buccaneer’s Creek with delightful guest quarters in two and three-story villas. With cobbled streets, fountains, plazas, reflecting pools and a large marina, it covers 55 acres of a former coconut palm plantation. Gentil organizateurs (the youthful French staff) lead gentil membres (guests) to meals to the strains of Fan Fare for Louis XIV. Similar to a land-based cruise ship operation, the Club offers tennis, sailing, yoga and gymnastics, water skiing, scuba, and a large beach. There’s dancing at lunchtime and at night, and the gentil organizateurs put on inventive shows a couple of nights each week. Most guests never stray from the exuberant village, content to wear Tahitian pareus (sarong-tied squares of hand-printed fabric) and strings of plastic beads, which are used to “pay” for sundries and drinks. Money is not used at the Club, except to settle the bead-counted tab before departure.

During a stay at the Club, I hired a car with two friends and explored sleepy fishing villages on the Atlantic shore. At Vauclin, we climbed a hill to the house of Martinique’s most prosperous net fisherman, one Celimene Simonau, a handsome black, then 64. Net or seine fishing, as it is called on the island, is ancient, its origins lost in time. Monsieur Simonau didn’t speak English, so our conversation was a melange of French, Creole (the local patois) and body English. We talked on the tiled porch surrounding his house, where a white porcelain drinking fountain and a used refrigerator were among things showcasing his success. In the kitchen a new 21-inch TV diverted his young wife as she chopped fresh vegetables. Simonau had 15 children, aged moppet to 42, and three of his six sons worked with him on the seines, the largest measuring over a half mile in length.

Martinique’s seine fishermen work from motorized gommiers, boats with rounded bottoms and hand-shaped braces, averaging 18 feet in length. The gommiers are named after gum trees, formerly the source of wood used by Carib Indians for dugout canoes.

Vauclin’s fishermen go out 50 miles or more to find their catch, Simonau said. At the fishing banks, nets are lowered from several gommiers. Fish are frightened into nets by beating the water with oars. “Lobsters are for the hotels,” he explained, “turtles for the city.” Thus, he subtly revealed the differences in table fare for tourists and local folk. A day’s haul may be 1,000 kilos, about a ton. Simonau measured his arm from the elbow down to show the size and length of the average lobster, which weighs around 11 pounds.

While plying their trade, Martinique’s fishermen sport straw bakouas, narrow-brimmed hats that have become the island’s trademark. (Martinique’s best-known older hotel, the Bakoua Beach, takes its name from the hat.) We stopped for a beer in Vauclin’s unpretentious little one-room bar after my time with M. Simonau. We were served with genuine courtesy and a great deal of curiosity. Tourists rarely stop in the tiny hamlet. Just out the door nets were hung to dry all along the shore.

The Bakoua Beach Hotel has held its own with recent refurbishing. Located on the Pointe du Bout, 20 minutes by ferry across the harbor from Fort-de-France, it shares a lovely peninsula with other newer hotels. The Bakoua has 98 rooms and suites, a garden setting, and a nice private beach. Night tennis, fishing, scuba, snorkeling, water skiing and launch trips to outlying untenanted beaches are among its many pleasures. The peninsula has the island’s best golf course. The popular Ballet Martinique stages folkloric shows in the Bakoua’s night club, where a sumptuous buffet dinner is included in the price.

Adjacent to the Bakoua Beach is the deluxe Meridien Hotel, built by Air France. It, too, has its own beach and all the resort comforts. In the casino, the roulette tables get as crowded as any in France. However, an admission fee is charged, and gamblers’ takes aren’t as liberal as they are in Las Vegas.

About an hour’s drive north of Fort-de-France is Plantation Leyritz. Originally a banana and coffee plantation, it’s been turned into a fine inn by Mme. Yveline de Lucy de Fossarieu, a Creole White aristocrat. Bedrooms are reached by a graceful curving staircase carved from island woods. The first floor and guest rooms are furnished with colonial antiques. The dining room is so good that France’s President Giscard d’Estaing played host there to President Gerald Ford during their historic meetings in Martinique. It’s worth a visit for the food, and a quiet hideout for those who want to read, walk in the gardens, swim in the pool.

Between these two extremes – modem sophistication vs. the two-foot-thick stone walls of Plantation Leyritz – are several modest hostelries on quiet beaches.

The plantation where Napoleon’s Empress was born, La Pagerie, has a pleasant little museum. Memorabilia include prints, letters and the personal possessions of Josephine. In the garden is a gazebo with a gift shop and bar. Owned and maintained by Martinique veterinarian Dr. Robert Rose-Rosette, it’s a pretty place.

Columbus discovered Martinique in 1502.The French followed a wise course in notrushing to lure tourists there until theirneeds could be handled well. Frenchlogic – whetner applied to formal gardensin Versailles, or to packaging soaps, or tothe beauties of a Caribbean island -expands horizons with grand panache.Visitors to Martinique soon appreciatethat.

Related Articles

Home & Garden

A Look Into the Life of Bowie House’s Jo Ellard

Bowie House owner Jo Ellard has amassed an impressive assemblage of accolades and occupations. Her latest endeavor showcases another prized collection: her art.

By Kendall Morgan

Dallas History

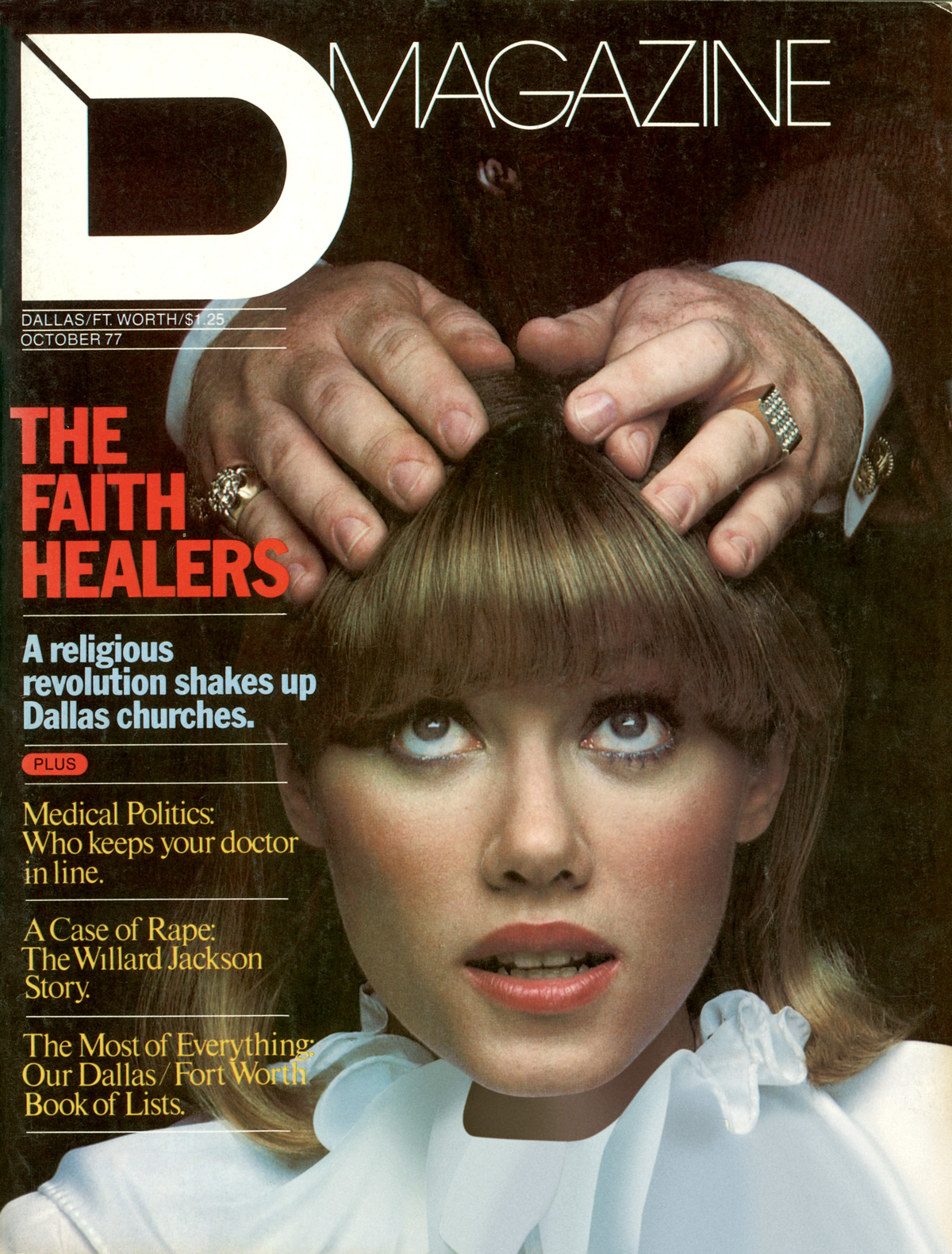

D Magazine’s 50 Greatest Stories: Cullen Davis Finds God as the ‘Evangelical New Right’ Rises

The richest man to be tried for murder falls in with a new clique of ambitious Tarrant County evangelicals.

By Matt Goodman

Home & Garden

The One Thing Bryan Yates Would Save in a Fire

We asked Bryan Yates of Yates Desygn: Aside from people and pictures, what’s the one thing you’d save in a fire?

By Jessica Otte