Cosette, then a plump but sprightly-looking matron of 52, supervised the festivities in a specially tailored captain’s suit, complete with gold piping, eagle insignia, and white yachtsman’s cap. But Erle Rawlins Jr., who escorted Peggy McCloud to the ball, recalls that the atmosphere was forced. “People attended not because they particularly wanted to,” Rawlins says, “but because Cosette had achieved some notoriety with the Mickey Ricketts episode, and everyone was curious. She had made a big to-do about the ship and had of course invited all the right people.” But the debs were uncomfortable having to dress up in Cosette’s costumes, and they didn’t know what to do with the kittens. People did not stay late. Rawlins, who interpreted the deb ball as a large-scale attempt on Cosette’s part to enter Dallas society, felt she was unsuccessful. Having finally gotten a good look at her, people simply regarded her as a greater curiosity than before.

In voluminous reminiscences written in later decades, Cosette recalled the deb ball as a perfect success: “At night, under the stars, guests would exclaim: Who would believe that we are in Dallas instead of some far-off island or on some exotic oasis in another world?”

• • •

Retired Highland Park Chief of Police Millard Gardner recalls that his office began to receive complaints from the Newtons’ neighbors about the ship almost immediately after the deb ball. Cosette had circulated another flyer, picturing and describing the ship, with a phone number to call for those interested in private parties: “’Captain’ Newton’s invitation includes dancing, swimming, luncheons, bridge, barbecues, picnics, clubs, and organization meetings,” it read. So there seems to have been some truth in subsequent accusations about zoning violations. Although Cosette denied receiving money for use of the ship, she held bridge parties, high school graduation parties, gave Red Cross classes, exercise classes, parties for servicemen and women, always nattily attired in her captain’s suit.

Initially, Chief Gardner simply issued an informal order to Cosette that there be no band music on board after midnight, which she apparently respected. But neighbors’ complaints persisted: The ship was built for a deb ball, wasn’t it? Wasn’t it supposed to be a one-time-only affair? And now there was a steady stream of strangers in and out of the block, clogging the streets with their cars and noise. Although no lawsuit was filed until 1953, with these complaints began one of the longest, most bitter, and bizarre neighborhood feuds in the history of Dallas, dragging on for the next 20 years and culminating in the auctioning off of 4005 Miramar and the razing of the ship and house.

Between 1942 and 1953 or so, the story is shadowy and difficult to pin down with precision. Dr. Frank recalls that Cosette closed the ship, in response to neighbors’ complaints, within nine months after it opened. The next clear fact is the filing in 1953 of Town of Highland Park v. Cosette Faust Newton et ux, which demanded the ship be dismantled.

Where did the ugliness begin?

Kathleen Gibson, who lived directly east of the Newtons and once demanded $30,000 in damages from them, won’t say much. “I would hate to tell you what we went through. Oh, the stories! He was a fine doctor, but it was awful. If there was something pleasant, I’d talk.” Angus Wynne II, who lived across Miramar from Kathleen Gibson and joined her in the suit for damages, flatly refused to talk. What follows is a reconstruction based on Cosette’s voluminous written accounts and Dr. Frank’s reminiscences, along with an occasional newspaper story and excerpt from court documents.

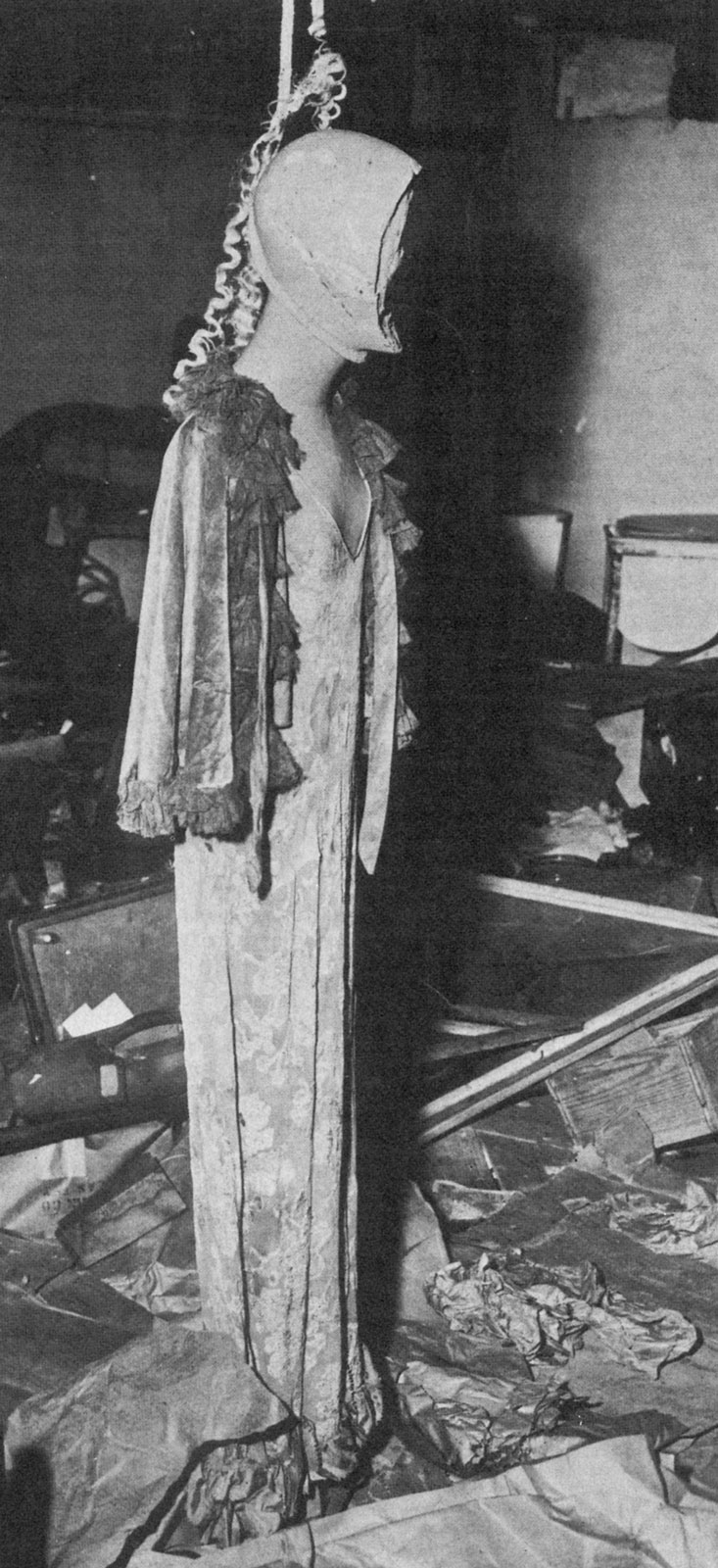

According to Cosette, the fault lay with “juvenile delinquency.” Vandals began to raid the defunct but still tantalizing mock yacht soon after its closing, she claimed, and with increasing boldness, progressively destroyed it, the house, and its possessions as well. Over the years, Cosette would charge Highland Park’s “rich youth” with breaking and entering, obscene calls, knocking holes in her fence, throwing the ship’s furnishings into the swimming pool, poisoning her dogs, tearing up clothes, and smashing her dishes, throwing acid on her shrubs, and hanging effigies on the property. According to newspaper accounts, by the late ’40s the Newtons had hired a night watchman to guard the house. And when, in 1949, the watchman’s child drowned in the ship’s swimming pool, Cosette claimed that it took the fire department 45 minutes to extricate the small body, the water was so choked with debris.

I spoke to no one who admitted vandalizing the Newtons’ property, nor did I encounter anyone who denied that serious and continued vandalism against the Newton property took place.

Meanwhile, apparently throughout the same two cloudy decades, the Newtons engaged in attempts to repair and fortify their property against further damage. Neighbors recall that crews of up to 15 men worked continually at 4005 Miramar. And court transcripts include Cosette’s list of defensive maneuvers between 1943 and 1953: a $3,500 metal roof to cover the driveway, “so that the boys can’t throw tacks”; electric doors to the garage; a 9-foot fence; watchdogs; $5,000 worth of barbed wire.

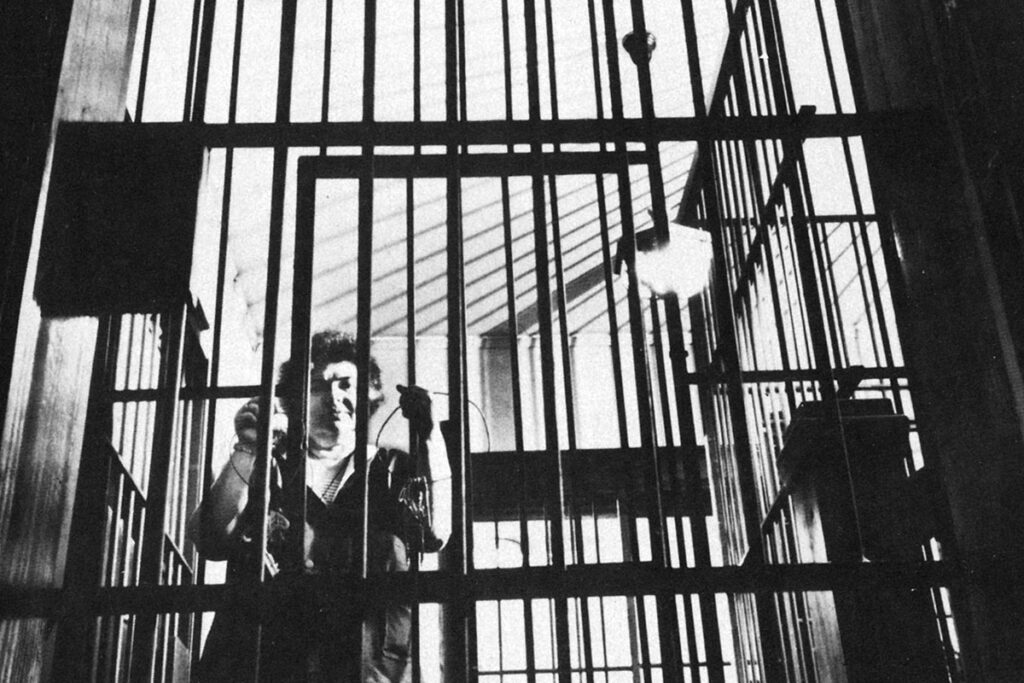

By 1953, photos indicate that 4005 Miramar was an armed fort. It was surrounded by a cyclone fence topped with barbed wire, and jail bars, bought from a prison supply house, adorned every window and entrance to the house and all the rooms between.

A flurry of charges drew sharp lines between Cosette and her neighbors — the Wynnes, Paschalls, Kennedys, Alexanders and Comptons to the north, the Lewises, Cades and the Gibson sisters to the east and west. Until her death, Cosette maintained that the damage was being done by the rich children of Highland Park, who were never caught or prosecuted by the authorities because vandalism was part of a persecution plot to make her flee the community.

Some claimed, however, that Cosette had her workmen do some of the damage to the property herself. And, in fact, the foreman of the work crews said that Cosette had had him knock a hole in the brick wall across the back yard. To further cloud the issue, however, Chief Gardner remembers arresting the same foreman for theft, after Cosette accused him of carting off two truckloads of household fixtures — toilets, pipes, sinks — to furnish his own home in Grand Prairie. These charges, however, were dropped.

Whether caused by vandals, workmen, or Cosette herself, there is no doubt that the state of the property worsened dramatically. An early photo shows 4005 Miramar with a new brick facade, banked on two sides with spacious, covered porches, its windows shaded with bright, striped awnings. On August 13, 1959, the Times Herald ran a story headlined, “Newton House, Long Abandoned, Damaged Heavily in Vandal Raid.” According to the story, “The Highland Park residence … now holds only old furniture, some private papers, and carpet padding.” It quotes Highland Park Police Chief W.H. Naylor as saying, “Kids are coming there from all over Dallas County. The rumor has got out that the place is haunted.”

Angus Wynne III recalls life on the block during the late ’40s, ’50s and ’60s: “It was a circus. Police cars were constantly patrolling the Newton house, Cosette gave sporadic public tours of the wreckage, there was construction, destruction, wild stories, pranks, reporters, cranks. The street looked like Lakeside Drive during azalea season.”

One person who did not find Cosette to be at all crazy was Addison Bradford, her attorney until 1962. Highland Park v. Cosette Faust Newton was one of Bradford’s longest cases, and he fought diligently for her although he warned her from the beginning that she might well lose. He was obviously sympathetic toward her, explaining to me that she had, after all, been entertained by royalty, was known internationally as a lecturer and had traveled the world over. All in all, Bradford seemed to feel the trial, while protracted with endless complications, was also a most instructive legal experience, whose convolutions exposed him to all points of constitutional and civil law.

And thanks to Cosette, the trial was also colorful and humorous. “She was a brilliant woman,” says Bradford. “A lot of people said she was crazy, but she was crazy like a fox.” Bradford was especially delighted by Cosette’s ability to confound Angus Wynne, who intervened in the suit on behalf of Angus Wynne II, Kathleen Gibson, and other neighbors. Among other things, the motion demanded $30,000 in damages because, it contended, no one would purchase property surrounding 4005 Miramar. Bradford recalled that Cosette would tantalize Wynne by continual references to her diary. Wynne would ask her about some detail, and she would reply that she couldn’t remember; she would have to look in her diary. Finally, Wynne asked to see it. Bradford objected on the basis of invasion of privacy. Wynne filed a motion to get it. Bradford fought him, and after a long afternoon of arguments, Judge Long ruled in Bradford’s favor. At this point, Bradford said, Cosette turned to him and said, “If Mr. Wynne wants to see my diary so badly, let’s let him see it.” She took it out of her bag and handed it to Wynne, who took one look at it, and threw it down in disgust. The diary was written in a polyglot language, Cosette’s idiosyncratic combination of the four or five languages in which she was fluent. It was totally indecipherable.

• • •

Author