On a pledge break during the March “Festival ’77,” the great stone face of Tom Landry appeared, hawking memberships in Channel 13 with the same impassive conviction he uses to sell sausages. When KERA reporter Norm Hitzges asked him what his favorite public television programs were, however, Landry admitted that his job doesn’t leave much time for TV-watching.

That perhaps points out Channel 13’s problem as much as anything: everybody’s for it but nobody watches it.

The figures seem to bear that out. Channel 13’s audience at any given time of day is so small that, when measured in terms of the kind of audience commercial TV attracts, it is practically not there at all. Recent Nielsen figures, for example, indicate that in the 9:30 p.m. Monday-through-Friday slot, Channel 13 averages only 1 percent of the available audience, and 2 percent of the sets that are actually turned on. That means that Channel 13 is being watched in only 18,000 out of almost 1.6 million potential homes. Station manager Ed Pfister admits they are “lucky” to get that available 2 percent.

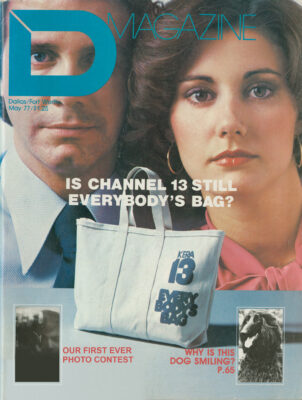

But Channel 13 prefers not to talk a-bout the size of its audience. The figure that matters to it is the number of citizen members. Membership now hovers somewhere around 40,000 (the station waffles a lot when asked for exact figures). Whatever the exact figures may be, the memberships are, as the people on pledge breaks constantly insist, the life blood of Channel 13. They constitute more than 40 percent of the station’s revenues. That’s why Channel 13 must constantly seek new members.

Nobody likes pledge breaks – they are boring at best; irritating, offensive, un-aesthetic hucksterism at worst. But they get results. “Festival ’77” in March brought in more than 6,000 pledges (at a minimum of $15 apiece) during the two weeks of special programming. Barry Wells, the station’s vice president for marketing, says it was “the best ever,” and he says it with some relief since last winter’s drive fizzled.

Who Pays the Piper?

“You never know when people are going to start seeing you as a shill,” says Ron Devillier, former vice president for programming at KERA, now director of program acquisition for the Public Broadcasting Service in Washington. “I personally feel we were doing too many pledge nights. But if in any three months the membership money quit coming in, the station would fold.”

The argument for supporting a station by citizen membership is an old one – based on the premise that he who pays the piper calls the tune. While the majority of the country’s public television stations are owned and operated by universities, colleges, school districts and municipalities, the country’s most influential public stations – WNET in New York, WGBH in Boston, KQED in San Francisco, WQED in Pittsburgh, WETA in Washington – are community stations owned by their members, at least in theory. They are the freest, most experimental, it is said, because of the diversity of their memberships. Or as the former president and general manager of Channel 13, Robert A. Wilson, puts it, “It creates an effective heat shield if you have 50,000 people giving you $20 each instead of 20 people giving you $50,000 each.”

But in fact who pays the Channel 13 piper? According to the latest market research study done for the station to help sell advertising for the Prime Time program guide, the median age of KERA’s members is somewhere in the 40’s, 85 percent of the women and 94 percent of the men are college-educated, their household income is likely to be over $20,000, and most of them have two cars and a Sanger-Harris charge account. In short, citizen members of Channel 13 are middle class and great numbers of them live in North Dallas.

Channel 13 officials say that demographics don’t influence programming, though it’s clear from program scheduling alone that the interests of the “typical’’ Channel 13 viewer have a great weight on what gets shown, and when. Programs like “Black Journal,” “Black Perspective on the News,” and “Woman” fall into late night slots like 10:30, while shows aimed at the middle class viewer, such as “Wall Street Week” and “MD,” have the prim-est of prime time slots. Cultural programming – the Boston Symphony, ballet and opera – is also important to attracting members and viewers. The recent live telecast of La Boheme from the Met drew in 400 members, and Barry Wells says “We have a very appreciative audience for the Boston Symphony,” indicating that they show their appreciation by giving money. The emphasis on cultural programming has affected the KERA-FM radio station, which recently adopted a 60 to 70 percent classical music format, dropping many jazz and ethnic programs, as well as live broadcasts of Dallas City Council meetings.

Tony Garrett, once program director of the radio station and reporter for “The 9 O’Clock Report,” views the radio changes and Channel 13’s claim to being a “community” station as nothing short of “hypocrisy.” Garrett says “Channel 13 exists on public money and tax funds, it gets special postal rates and sales tax exemptions. Its mission is to serve the community – the community of North Texas – but in performance it’s demonstrated only a kind of semi-liberal Eastern elitism.” Garrett takes aim at KERA’s practice of broadcasting middle class sports events like tennis tournaments. “Why don’t they televise the Mesquite Rodeo, for example? There’s a cultural phenomenon right in our backyard. Why does the membership of Channel 13 have to come from one ’core’ group? Why don’t they try to develop an audience in that diversified community they claim to serve?”

Ron Devillier admits that his greatest disappointment with his performance in Dallas was that he never got around to developing more programs for the community as a whole. Devillier’s record as program director for Channel 13 was so good – he is credited with being the man who “discovered ’Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ ” – that he moved on to a similar job on the national level. On Channel 13’s performance in aiming programs at a larger audience, Devillier says, “I think its record in that regard is unsatisfactory.” But Devillier also insists that the station “never avoided an issue because it would offend North Dallas.” And according to Jim Lehrer, another former KERA staff member who went on to bigger things in Washington, Channel 13 has a reputation within the public broadcasting system for being “the station that broadcasts everything – no program is too controversial for it.”

Ed Pfister professes to agree that KERA’s programming may be too narrowly focused, and that Channel 13’s continued growth depends on broadening its appeal. He regards the slowdown in membership growth last winter as one of the major “setbacks” of his first year in the presidency of the station. “Public TV programming reaches a dedicated and committed group, but we have to expand the audience,” he says. It’s one of those public-spirited ideas that everyone agrees on, and nobody is able to implement.

Spending Money to Make Money

Pfister’s concern for the growth of the station’s membership is largely an economic one, but he is surely also aware that the prestige of KERA within the public television system is based in large part on its rapid membership growth. In 1970, when the change from an educational format began, there were 2,000 members. By 1975, there were 27,000. Then, in 1975, the station began making a big push for membership, switching from occasional”pledge night” appeals to big splashy “festivals,” four times a year, when special programming would be ballyhooed, though it would also be interrupted frequently by long appeals for membership support.

Barry Wells, who took the marketing job three years ago, thinks membership should reach 60,000 “probably next year.” As for the fact that people are irritated by pledge breaks, Wells says, “We’re sensitive to that, but on the other hand four thousand people joined the station last time. We’ve experimented with different types of breaks – isolated nights, spot breaks – but that doesn’t initiate support the way the concentration of efforts during the four festival weeks does.”

One problem with constant fundraising is that it takes money to make money. The budgeted expenses for the station’s promotional activities – including the Prime Time program guide, staging the auction and the “festivals,” and keeping records on the station’s members – have jumped from 17 percent of the station’s expenses in 1975 to 30 percent in 1977. A large part of this increase may be accounted for simply by growth: if you have more members, you need to keep more records, you need to print more copies of Prime Time, and you have to hire more staff to take care of them. But trying to attract new members accounts for a lot of it. The cost of premiums – tote bags and record albums, Big Bird dolls and National Geographic Atlases – has skyrocketed. The station spent around $33,000 on them in 1975 but over $100,000 for them in 1976.

It needs to be pointed out that Channel 13 is not isolated in its efforts to build membership through pledge appeals and premiums. Nearly all community-owned PBS stations use the same gimmicks, and the nature and frequency of some of them has led to a recent Federal Communications Commission inquiry. The FCC is primarily interested in keeping an eye on promotional announcements for products and services, but it also expresses concern about auctions (“we are inclined to question whether it is basically in the public interest for ETV stations to devote a number of days each year essentially to the ] process of promoting products and services, and selling them at the highest possible price”) and about the frequency, duration, and percentage of the broadcast day devoted to membership drives. Public TV stations, according to a recent study, spend about 16 percent of their air time on self-promotional activities, to earn an average of around 13 percent of their income. (The percentage of income earned in this way by community-owned stations is, of course, much higher.) Commercial stations are allowed to use 24 percent of their air time for advertising, which earns virtually all of their income.

If Ron Devillier’s assertion that the station would fold in three months if the memberships stopped coming in is true, then the station could be skating on such thin ice that something must be wrong with its financial management. While dependence on memberships is all very well forgiving people a sense that they are participating in the very existence of their public TV station, a station which hopes to be a community institution should have a surer grasp of its long-term financial future. The station’s income from investments currently accounts for only one percent of the station’s revenues. Running a station primarily on memberships is like trying to run a university on tuition alone.

The Urge to Go Network

The station also earns money from some of its productions, largely those it does for the Dallas County Community College District. But for a long time, KERA has had its eye on the bigtime: nationwide distribution of a Channel 13-produced series through the Public Broadcasting Service. PBS, created in 1969 and restructured (largely under the leadership of KERA’s chairman of the board, Ralph Rogers) in 1973, is the programming and distribution authority for public TV. American public television is not a network in the sense that CBS is, or even in the sense that a non-commercial system like the British Broadcasting Corporation is a network. But though “independence,” “autonomy,” and “grassroots localism” – the last a phrase that gained currency during the Nixon administration’s criticism of PBS public affairs programming – are bywords in American public broadcasting, the consortium of individual stations is centralized in the Washington bureaucracies of CPB and PBS. In order to get nation-wide distribution for a KERA program or series, the station would have to work through PBS.

So far, the station has had only individual programs – never a series – sent out by the network although the popular “MD” program has been picked up by the Southern Education Communications Association (SECA) network of 75 stations in the Southwest, and is being looked at by several other such consortiums.

“Woman Alive” – But Just Barely

In 1973, KERA almost hit the network with a program, “Woman Alive,” it developed in cooperation with Ms. Magazine. The grant for the project came from the CPB, which earmarked funds for a woman’s program and invited program proposals from individual stations. Bob Wilson came up with the idea of working out a project in cooperation with Ms., flew to New York, and talked out the details with Gloria Steinem and Pat Carbine. The resulting proposal was a winner.

But when it came to actually getting the pilot on film and ready for airing, it was obvious that KERA’s facilities were being stretched to their limits and that the long-range communications between Dallas and New York were simply not working. The project, according to producer Joan Shigekawa, was simply too ambitious for the station at that time. “Wilson and everyone were pushing for the best quality a-vailable. But the problem was, to give an example, that we would shoot footage on the best film stock available and then discover that none of the labs in Dallas was able to process it.”

The completed pilot was at least “airworthy,” as Ron Devillier calls it, though Joan Shigekawa regards it as a success: “It got terrific reviews.” But it came in well above cost. The decision was made to turn it over to New York’s WNET. The loss of “Woman Alive” was something of a blow to the station’s morale, although it was more of a blow to the budget. As Devillier recalls, the show came in at $125,000 when it was budgeted for $75,000.

Bob Wilson: Style Without Substance?

Some have seen the “Woman Alive” project as symptomatic of what went wrong at KERA under Bob Wilson’s leadership. Wilson is not an easy character to get a handle on. Some of the staff, chafing under Ed Pfister’s tighter control and his more rigidly-structured organization, look back nostalgically at the days when Wilson was in charge. Wilson is characterized as “impetuous,” “wildly enthusiastic,” “flashy.” One of his admirers is Jim Lehrer, who admits at the outset that Wilson is a “very controversial figure.” But from a very personal point of view, Lehrer found Wilson a “most energetically supportive person who wanted quality and supported me in every way. He brought me into television, and ’Newsroom’ was the result of his energy and vision, not mine. He never interfered, so in terms of any way I could have of evaluating him, I’d have to rate him ’A.’ ” Wilson’s great advantage as manager of KERA, according to Lehrer, was his rapport with board chairman Ralph Rogers, whose administrative assistant Wilson had been before taking the Channel 13 job. “We’d get together on something,” Lehrer says, “and Wilson would say, ’that’s my position, let’s go fight with Ralph.’ He and Rogers are very close, and they fought like affectionate cats and dogs.”

But if there is a down-side to Wilson’s career as KERA manager, it is his impetuosity. If “Woman Alive” was a case of too much, too soon, it was at least a project that got off the ground. “Wilson was a great PR man,” one station old-timer says, “and I guess he was good for the station on balance. But he shot from the hip, and never followed through on anything. The turnover rate at the station was 65 percent – I think he had five or six secretaries a year – and I think everyone was relieved when he quit.”

Wilson’s whimsy often resulted in erratic managerial decisions. Tony Garrett, who speaks with some affection and admiration for Wilson’s imagination and style, admits that Wilson “would go through ten ideas before he’d come up with one that really worked. One time he decided it would be great if the station could lease or buy the old Knox Street Theater and show old movies there to raise money for Channel 13. So he put me in charge of finding out everything – who owned the theater, how much it would cost, how much film rentals were, and so on. I worked my tail off and turned in the report several weeks later. Wilson looked at it and said ’What’s this?’ I told him, and he said ’Oh,’ as if it were the last thing on earth he had any interest in, and tossed it on a stack of papers. That’s the last I heard of it.”

The Golden Age of “Newsroom”

Wilson’s major contribution to the station was generating the idea for Channel 13’s greatest programming success, “Newsroom.” The idea for the program actually originated at San Francisco’s KQED, when during a newspaper strike reporters appeared on the public television station to give the day’s news. Reaction to the show was so positive that KQED was able to talk the Ford Foundation into funding a regular news-analysis show with actual reporters (rather than golden-throat Ted Baxter types) delivering the news and opinions. Wilson was quick to see the possibilities for such a show in Dallas, and he hired Jim Lehrer, a former city editor for the Times Herald, to work with him on a proposal for the Ford Foundation’s funding such a show on KERA.

“Newsroom” was, quite simply, the most exciting and influential local public affairs program Dallas has seen, and it still evokes nostalgia from the devoted who watched it in the Lehrer years. At 6:30 every weekday evening, the Beatles anthem, “Here Comes the Sun,” would launch 45 minutes of give and take from reporters and guests seated at desks drawn up in a circle around the moderator, Jim Lehrer. Reports on city council meetings, commissioners’ court sessions, school board decisions would be followed by probing questions and comments, sometimes generating fresh assignments on air – “Look into that and give us a report tomorrow,” Lehrer would tell a reporter who couldn’t come up with an instant response. At the end of the show, “feedback” calls from viewers would often generate further stories. There was a sense of spontaneity, and of participating in the actual process of reporting the news.

In 1970, Dallas was ripe for a program like “Newsroom.” Both newspapers were notably unaggressive in investigative reporting, and local news reporting on the three television stations was not better. Lehrer and Wilson kept tabs on the 6 p.m. Dallas news broadcasts and found that local news took up only seven to ten minutes of the half hour program. In proposing an analytical local news program for Dallas, Lehrer and Wilson commented, “The public officials of this area are not used to having their views and actions closely analyzed. Neither are any of the o-ther business, civic, and cultural leaders of the area. No doubt they will not like it.”

They didn’t like it. Courthouse officials especially chafed under “Newsroom’s” scrutiny, though few were so vocal as County Judge Lew Sterrett, then the county’s most powerful elected official, who referred to one of “Newsroom’s” black reporters as “that colored boy” and as a “jigaboo,” a fact that “Newsroom” staffer Mike Ritchey reported on the air.

But Dallas in 1970 was filling its northern rim with young professionals, many of them from the East and West coasts, others returning from the University of Texas at Austin, who were skeptical and even irreverent toward the Dallas Establishment. “Newsroom” told them what was going on, how a new superintendent of schools named Nolan Estes was planning innovative but costly programs for the Dallas public schools, how a group called the Citizens Charter Association dominated elections to the city council, how the county commissioners had a habit of going behind closed doors whenever real decisions had to be made. And in the case of the commissioners court, Mike Ritchey even went so far as to file suit against it when the doors were closed in his face. It was the core of young professionals, hungry for information about the city that had become their destiny, that formed “Newsroom’s” audience – and became the base on which Channel 13 was to grow, to become a phenomenon in public broadcasting, and to become a major Dallas cultural institution and an outlet for the volunteer energies of the middle class.

What Happened to “Newsroom”?

Some of the spark began to go out of “Newsroom” in 1972, when Jim Lehrer left for PBS in Washington. Lehrer and Wilson went to “Newsroom” reporter Darwin Payne to persuade him to take the moderatorship. “I was reluctant,” Payne says. “I wanted to go back to SMU and teach, and I knew it was going to be terribly difficult to replace Jim. Basically, I took the show on the assumption that the director was in charge. But Wilson and I locked horns on lots of things. I had hired Bronson Havard, a solid newsgath-erer and terrific with ideas, but he didn’t have a good television presence, and there were many complaints. Wilson fired him – in a brutal fashion. Finally he just arbitrarily fired me, by registered letter.”

Payne’s successor was Lee Clark, who had been one of the first people hired by Lehrer for “Newsroom.” Originally a consumer reporter who would review restaurants, or do reports on where to buy good bread, Clark moved into political reporting during her husband’s term in the state legislature. Of the original team of reporters, Clark, with her quick recall of specific facts and keen delivery, made a sharp impression. One of the Ford Foundation’s team of observers, who would come quietly into town ànd watch the program without the staffs knowledge, wrote that she was “a simply amazing television reporter. Pleasant to look at and listen to, Miss Clark manages continuous eye contact with the camera, just a virtuoso act of discipline; indeed, at times I wished she would glance down at her copy just to show she was mortal.”

Under Lee Clark’s administration, which lasted until last fall when Ed Pfister began to reshape KERA’s public affairs programming, “Newsroom” became a more tightly-run program. Gone were the desks drawn up in a circle around the moderator. Clark was at the head of the table around which sat reporters like Jim Atkinson and John Merwin – to name some alumni – and others who remain with the show, like Steve Singer and Susan Caudill. Reports became crisper, and give and take was kept to a minimum. To some observers, Clark’s own “virtuoso act of discipline” seemed to be becoming rigid-ified into a model. The spontaneity and humor were missing, and “Newsroom” began to look like just another news show.

Meanwhile, things were happening to Dallas journalism. The Times Mirror Corporation bought the Dallas Times Herald and installed Tom Johnson as editor, sparking new life and new competition between the papers, and initiating a stronger investigative reporting policy. Competition between the television newscasts inspired not only cosmetic changes in sets and anchor personnel, but also in reporting and investigation, particularly on Channel 8’s news, which both Bob Wilson and Darwin Payne now single out as having something of the spirit “Newsroom” once had. Magazine journalism began to go local, too, first with Texas Monthly’s occasional pieces on Dallas and then with D Magazine’s appearance in 1974. “Newsroom” began to look rather old hat, and more than one staff member thinks the station management lost interest in it. “Their attitude seemed to be, ’Who needs “Newsroom” now that Channel 8’s so good?’ ” one of the “Newsroom” staff says.

Pfister “Shakes the Public Affairs Tree”

When Ed Pfister took over from Bob Wilson as station manager last year, he took a good look at “Newsroom” and saw that it was moribund. He responded to the situation by restructuring the public affairs division of the station, announcing the surprise appointment of Bill Porterfield as executive producer, and making a hefty financial commitment to the program. But the problem with committing so much money to a local public affairs program is that the only way the station can profit financially from it is by building a large and enthusiastic audience – one that is willing to join the station in support of it. Ron Devillier for one thinks Pfister “got bad advice” on the financial commitment, and that the subsequent retrenchment that took place was inevitable.

“Newsroom” became “The9O’Clock Report” in October of last year. The new time slot was Ed Pfister’s idea – one that was strongly opposed by the staff, and one that he now regrets. The attempt to attract younger viewers, in part by stacking “The 9 O’Clock Report” so that big draws like “Monty Python” followed it at 9:30, didn’t work. It had a recycled look, as if it had borrowed sets and format from Channel 8’s news, which got much of its impetus, ironically, from the old “Newsroom.” So in February of this year, the program, renamed “13 Report,” was moved back to a 7 p.m. slot, following the popular “MacNeil/Lehrer Report,” and using a format much like that show’s. Instead of reporting the news of the day, programs deal with single issues, with guests appearing to present their sides of the issues.

When the time and format change was announced, the program’s staff was thunderstruck. The decision had been made without consulting them, and morale was at a low ebb. Things seem to have settled down now, but “13 Report” remains a derivative and troubled program, and it still looks recycled.

Ed Pfister now says “we have shaken the public affairs tree,” a rather cryptic comment that some interpret as a favorable statement while others view it skeptically. One staff member says, “Pfister gives you mixed signals – probably a management technique he’s read about, designed to keep you guessing, and keep you on your toes.” Optimists feel that things are shaping up, but there is a hardcore group of pessimists. There is even a paranoid fantasy that some of them recount in jest, though the joke is that of a demoralized staff. Perhaps, they say. Pfister’s commitment to public affairs programming was like the “Springtime for Hitler” play in Mel Brooks’ film The Producers – a project intended to fail from the start, so that Pfister would have a good reason for killing it completely.

Ed Pfister: A Change In Style

Pfister’s task as station manager is made harder because of the marked difference in style from his predecessor. Where Bob Wilson was outgoing, Pfister is reserved; where Wilson was volatile, Pfister is relatively cautious. And there is no doubt that as far as the station personnel are concerned, Pfister came in under a cloud. Almost everyone at the station wanted the personable, easy-going Ron Devillier to succeed Wilson. Devillier, it was thought, had grown up with the station, knew its problems and its potential, and had an excellent rapport with the people who worked there. Pfister had begun working for Ralph Rogers in Washington in 1972 as director of the Chairmen’s Coordinating Committee which hammered out the CPB-PBS agreement that restructured the Public Broadcasting Service. Then when Rogers became chairman of the board of PBS, Pfister moved in as his executive assistant. Since Bob Wilson had been Rogers’ assistant at Texas Industries before becoming KERA manager, Pfister’s succession was viewed as Rogers’ way of ensuring his influence at the station will continue once he steps down as chairman of the board of KERA.

“The fact that Ed Pfister had worked for me for four years obviously made it possible for me to recommend him to the selection committee with confidence,” Ralph Rogers says, denying that any sort of power play took place. As for Ron Devillier’s candidacy for the job, Rogers will comment only that “Devillier never had the slightest managerial experience. He’s a superb programmer, and he now has a job in Washington that he’s eminently qualified to fill.” Rogers feels that his relationship with Pfister has to be seen in terms of a baseball metaphor: “The manager calls in someone from the bullpen and then walks away. That’s what I did when I suggested Ed Pfister for the job. But the search committee made the decision on hiring him – not me.” Of his relationship with Rogers, Pfister says, “Ralph Rogers doesn’t run the station. The board does. I’ve worked with boards for 17 years and this one is extraordinary- a group of serious-minded aggressive people.”

Pfister has faced the added disadva

tage that – unlike Devillier – he is not native son. His appointment was viewed as yet another instance of the “Eastern elitist” tendencies of the station. “You can’t go anywhere at this place,” one complaint runs, “if you didn’t go to Dartmouth,” a reference to Bob Wilson’s and Pfister’s assistant Bruce McKenzie. (Wilson and McKenzie are also, like Ralph Rogers, Bostonians.) Pfister didn’t go to Dartmouth, but he did go to a small Catholic college in Jersey City. And though vice president Barry Wells and creative services director Pat Perini are natives, the gripes persist that “Pfister doesn’t have any faith in Texans,” and that he “surrounds himself with Eastern cronies.”

Pfister hasn’t had an easy time taking charge of a group of talented and temperamental people, and he is candid about the setbacks of his first year. “I thought that by June 30 of this year we would have 60,000 members, possibly even 75,000. We won’t have that many.” Pfister also feels that the public affairs programming dilemma has resulted in a setback, “but we’re determined to find the answer. I want a program that celebrates this place.”

Has Public TV Lost Its Steam?

Channel 13 faces an uphill struggle not only because of local troubles, but also because of questions about public TV’s role nation-wide. As public television has built its audience, it has gone soft, not only looking more like the commercial networks, but sometimes even being surpassed by them. Isn’t “Roots,” for example, more entertaining and more controversial than public television fare like “The Pallisers”? Is “Monty Python” really better (or less jejune) than “Saturday Night Live”? Is “The Adams Chronicles” any less a soap-operatic view of history than “Eleanor and Franklin” (which was sponsored by IBM with a minimum of commercial interruption). Can PBS public affairs programming claim to be better than “60 Minutes” or “Who’s Who”? In short, does public television really provide an alternative service in any area except children’s programming?

But it’s easy to fault the public televi-sion system, which is hardly a “system” at all. It exists on the good will of a hand-full of faithful viewers and drops from the federal bucket. And there are times when it hardly seems to know what it exists for. “The greatest problem in public TV,” says Bob Wilson, is knowing the score. “After the last Ali-Norton fight, Pete Axthelm wrote a column in which he pointed out that boxing is the only major sport with a secret scoring system. What sort of fight would it have been if Norton had gone into the fifteenth round knowing they were tied seven-to-seven? In public television, we not only don’t know what the score is – in commercial TV you can compare ratings and audience shares and ad revenues – we’re not even sure what the scoring system is. Television isn’t a concept medium. It revolves around personalities, and Channel 13 has to search to define its personality.”

Ralph Rogers, who has made Channel 13 his business for almost ten years, blames public television’s plight on a failure of communication. “I really don’t think the people of this community,” he says, “understand what a public TV station is for.” He passes deftly over the why not? and goes straight into the why they should. “Our institution could be the most important, most constructive non-profit institution in the community. Educators in the United States who fail to use public television are derelict in their duties. Its potential has been proven with ’Sesame Street.’

“And thanks to public TV – with occasional specials on commercial TV, too – it’s possible for everyone today to listen to the greatest music, to see it performed, to see operas or musical comedy. And how many people ever saw a first class performance of a ballet before TV? You can go into great museums, talk to authors. There’s endless exposure to the riches of the world. No person in the world is so rich – culturally speaking – as the poorest person who watches television.

“And then there’s public affairs. I think the American public is frustrated because they don’t understand who governs them – what is the bureaucracy and how does it work? TV is the only way to get people to understand. The country’s too big – we’re not doing our job if people are turned off to politics.

“Public television is the only institution that exists that can bring the American people the kind of programming that will enable them to benefit educationally, culturally, and in the public sphere.”

He bangs the table for emphasis.

“That’s why we exist. I averaged 56 hours a week working on public television last year. Without pay. So to me gossip about whether I do or don’t like Ron Devillier is completely unimportant compared to what we’ve just been talking about.”

It is a masterful piece of salesmanship. Perhaps, it’s suggested, Ralph Rogers should go on during pledge breaks to sell public television instead of Tom Landry?

A succession of reactions flickers a-cross Rogers’ face at the suggestion – first annoyance, then amusement, and finally seriousness. “If things don’t get better,” he says, “maybe I will.”

After Ralph Rogers … What?

“Who the hell is Ralph Rogers that he carries so much weight around here?” one Channel 13 staff member grouses. “He’s the president of a cement factory.”

But he’s more than just the president of Texas Industries. As chairman of the board of Channel 13 for the last eight years, Ralph Rogers has been the most powerful man at Channel 13 – more powerful, some say, than any commercial TV station’s board chairman. His influence – his likes and dislikes – has been constantly felt, though Rogers insists, “I have no influence on programming. That’s a deliberate choice, because I have to be free to work for the station and to make impartial decisions.”

Jim Lehrer, the founder of “Newsroom”’ and now a Washington newsman for PBS, says, “He came to me when we were starting ’Newsroom’ and asked what he should do to avoid conflicts of interest. I told him, ’You’ve got to be clean. You’ve got to get out of your political involvements and anything else that could create a suspicion of bias.’ And he did just that. He knew how to handle the kinds of criticism we used to get from the business community about the things we reported, and he always dealt with me above board.”

Virtually everyone at Channel 13 uses the phrase “above board” about Ralph Rogers’ dealings, but that doesn’t mean that Rogers’ power isn’t felt, and often resented. “Newsroom” reporters complain that Rogers “never liked the program,” and suspect that the recent radical changes in the program’s format have been made in response to his criticism that they practiced “gonzo journalism.”

On the board level, Rogers is in firm control. Like many public stations, KERA is “community-owned” – governed at least in theory by the people who “join” by paying a minimum of $15 a year. Membership on the board is also theoretically open, but in practice the board is made up by a nominating committee, and to challenge one of the nominating committee’s selections, one has to present a petition signed by 3 percent of the station’s members – which means collecting more than a thousand signatures – and present oneself for election at the annual membership meeting which is, of course, attended by only a small fraction of the membership. No one, it almost goes without saying, has ever tried making the challenge.

Rogers himself insists that his role at Channel 13 was more important in the first three or four years of his service as chairman than it has been recently. “Back then,” he recalls, “we had a budget of $200,000 and an income of $ 100,000, so it was really necessary that the chairman be very active. Now my job is more conventional.”

But Rogers was very much in everyone’s mind -? if not on the scene – when Channel 13 reporter Tony Garrett recently tested the constitutionality of barring TV cameras from the death chamber dur-ing executions. According to reports, Rogers was furious when he found out about the suit, and called Ed Pfister to account for allowing it to be filed. Both Pfister and Rogers deny the reports. As for reports that Rogers had demanded that Garrett be fired, Pfister says, “I told one reporter that ’If Ralph Rogers fired Tony Garrett, he fired me, too.’ And I suggested the reporter check with Rogers who said to him, ’I would never fire Tony Garrett – he doesn’t work for me.’ ” A few weeks later, Garrett resigned.

For some time, rumors of Rogers’ retirement from the chairmanship of the KERA board have been going around. “You have a writer,” he says, referring to David Ritz’s profile of Rogers in the June 1976 issue of D Magazine, “who claims that I never spend more than eight years on any one project. That may be right, or it may not be – I’m not in a position to say.”

Who will succeed him? ’”We have two excellent vice chairmen, Betty Marcus and Emmett Conrad. Either of them would make a first-rate chairman.”

The “smart money” is on Betty Marcus, wife of the late Edward Marcus, who is well known for her involvement in the fine arts, but Emmett Conrad’s decision not to stand for reelection to the Dallas school board makes it possible for him to spend more time working for the station, in which he expresses a strong interest. Surely a Channel 13 led by a black physician from South Dallas would be different in character from one led by a member of one of the city’s most prominent business families.

Rogers is unwilling to comment. “The board runs the station, not the chairman,” he says.

Meanwhile, there is still Ralph Rogers. Some at Channel 13 find it as hard to imagine KERA without Rogers as it was to imagine China without Mao, Spain without Franco, or Ethiopia without the Lion of Judah.

Lee Clark: Upstairs, Downstairs?

There’s no person in Dallas, with the possible exception of W. A. Criswell, who elicits more disparate opinions than Lee Clark. She has been called “an absolutely phenomenal television personality” and “a power-hungry politician.” She has been lauded for her quickness and intelligence and damned for a voice one observer calls “a falsetto monotone.” She seemed a logical and for a time a successful choice to become moderator of “Newsroom” after Darwin Payne’s disastrous attempt to succeed Jim Lehrer in the job, but she has been blamed for making the program too stiff, too cut-and-dried. Nevertheless, she has been Channel 13’s one real media superstar – a sort of cool, patrician, brainy Judy Jordan.

That’s why the station’s recent decision to take Clark off the air and put her in the off-camera job of “director of program development” comes as something of a surprise. Ed Pfister explains that the job was created to fill the slot left by Ron Devillier’s departure. “Ron was in charge of both broadcasting – scheduling and acquisition of programs – and production – conceiving new programs and seeing them through to fulfillment. He and I agreed that they should be separate jobs, so we put Pat Perini in charge of broadcasting and I was delighted when Lee a-greed to take the production job. Our allocation for productions has jumped from $300,000 last year to $ 1,500,000 this year, so we need someone of her abilities in that position.”

But there is always more going on at a television station than meets the camera’s eye, and in this case it was an outright feud between Lee Clark and the rest of the public affairs staff. Many of them resented Clark’s domination of the program and claimed that she constantly played power games. Clark, on the other hand, was reportedly unhappy when Bill Porterfield was made executive producer of 13’s public affairs programs and until recently had been buttonholing individual members of the staff to make her complaints about “13 Report”” and its management well known. The tensions between Porterfield and Clark made Harry Reasoner and Barbara Walters look as chummy as the Captain and Tennille.

Ed Pfister denies that animosity between Clark and the public affairs staff led to the creation of the new job. “I don’t operate that way.” he says. “People have got to work things out between themselves.” As to whether Clark’s new job will give her any authority in Bill Porterfield’s public affairs sphere, Pfister says, “All my executives have input in one another’s areas, but the ultimate decisions will have to bePorterfield’s – with my option to changethem, of course.

Lee Clark says, “I found my seven years on ’Newsroom’ great fun, and I expect to < find working behind the scenes even more fun. KERA has long wanted to be a national production center, and I think the moment is right. Ed Pfister has devel- oped the production capabilities of the station, so i see my job in large part as . marshaling the energies of the staff." She expresses no regrets about leaving her < on-screen role.

How Good Is Channel 13?

It depends on what you’re looking for, of course. But there’s no doubt that within the public TV industry, Channel 13 is looked on with favor, while on the local scene it has considerable prestige as a cultural institution. But is it, perhaps, a sacred cow, a phenomenon created by the public relations savvy of former general manager Robert A. Wilson?

Jim Lehrer, who knows the station inside and out, first as the founder of “Newsroom” and now as the Washington-based co-anchor of “The MacNeil/Lehrer Report,” thinks KERA deserves its reputation. “It’s known as the station that runs everything – no program is too controversial for it, either in themes or language. It was one of the first stations to pick up “Steambath,’ which a lot of other stations thought was too raunchy. That surprised a lot of people who think of Dallas as uptight.

“It’s also highly thought of,”’ Lehrer continues, “because of the rapid development of its membership. It began as nothing seven years ago. ’Newsroom’ enhanced its reputation, and so did the personalities of Ralph Rogers and Bob Wilson.”

There’s no doubt that men like Lehrer, Rogers, Wilson, and former KERA program director Ron Devillier have been

energetic and often courageous in their attempts to build the station. But it can be argued that much of the achievement of Channel 13 has been in the area of self-promotion, that except for “Newsroom” it has had no major local programming successes, and that its growth, while phenomenal, has not achieved the level it ought to achieve or brought in the kind of income it really needs. Barry Wells, KERA’s vice president for marketing, says, “I think this station is capable of garnering 100,000 members.” Meanwhile, however, membership hovers somewhere around 40,000.

A measure of Channel 13’s uniqueness is that it is so much stronger – both financially and in terms of prestige – than other stations in this region. Houston’s KUHT, for example, is almost moribund; with little or no money for public affairs programming, it serves primarily as a feeder for PBS programs and local educational broadcasting. But one way of judging KERA’s status is to compare its membership and income figures (provided by the Public Broadcasting Service) with some of the country’s most successful community-owned public TV stations (see chart).

While KERA comes out looking pretty good in some of these statistics, such as the one that indicates that its individual members give almost $30 apiece, it’s worth pointing out a few things. One is that only financially-troubled San Francisco relied more heavily on income from subscriptions. Another is that WQED, in the smaller Pittsburgh area, had a larger station membership and a total income more than twice that of KERA.

So far, KERA hasn’t made the network bigtime. It is still aiming for that mark of distinction with its “Eyewitness” series, which will receive PBS-wide test screenings this July. It has other projects in the hopper, such as the series on Congress featuring ex-Congressman Alan Steelman and a historical drama about Spanish-speaking families of the Southwest tentatively entitled’ ’Centuries of Solitude.’’ But finding the money to undertake the risky business of making pilots is not easy. And more than one observer agrees with Jim Lehrer that “Channel 13 doesn’t need to do national programming. I don’t think it’s essential to their reputation.”

Local programming, it is argued, is what public television should be all about. But aside from “Newsroom,” the “Election Specials” that give local candidates a forum for debate, and a handful of excellent documentaries such as Ken Harrison’s “Jackelope,” the station has not been particularly creative in its local projects. Local actors, artists, musicians and dancers are quick to criticize the station for not providing a showcase for their talents.

Bill Porterfield. as the station’s public affairs director, thinks that is changing, and he cites a variety of proposals that are jn one stage or another of being approved or produced. They include a minority affairs and culture show (“black, brown, Indian – even redneck,” Porterfield says) being developed by Bob Ray Sanders, a sports show – with some potential for national distribution – by Norm Hitzges, a series on Texas politics by Dave McNeely, and special programming for women by Susan Caudill.

Porterfield gives Ed Pfister credit for the ideas for many of these shows. And others point out that, having spent 17 years in it, Pfister knows the Washington public TV bureaucracy and has important contacts there that can help ease the way for the station. The only question that remains is whether that way is the right one.

Related Articles

Hot Properties

Hot Property: An Architectural Gem You’ve Probably Driven By But Didn’t Know Was There

It's hidden in plain sight.

By Jessica Otte

Local News

Wherein We Ask: WTF Is Going on With DCAD’s Property Valuations?

Property tax valuations have increased by hundreds of thousands for some Dallas homeowners, providing quite a shock. What's up with that?

Commercial Real Estate

Former Mayor Tom Leppert: Let’s Get Back on Track, Dallas

The city has an opportunity to lead the charge in becoming a more connected and efficient America, writes the former public official and construction company CEO.

By Tom Leppert