I The Main Streeters

The brick is from Germany, the gleaming marble from Italy. The showcases are exquisite pieces of carved mahogany – solid, dark, rich. A small, discreet orchestra plays turn-of-the-century fare, variations on the patriotic melodies of John Philip Sou-sa. It’s a lovely party in a magnificent new store, with stained glass windows, thousands of electric light bulbs, glittering jewels and majestic blue-veined columns which stand side by side like proud soldiers. The sense of refinement, of European taste, contrasts sharply with what is otherwise a small and casual Southwestern town: Dallas, Texas, in the year 1899.

The city has never seen anything like the new Linz Building which rises from the ground floor jewelry store to a seventh story roof garden, the tallest skyscraper in the region.

Jewish and gentile civic leaders chat and mingle cheerfully with one another, roaming through the store and marveling at the precious merchandise. Certainly it’s a proud moment for Dallas, but it’s a particularly proud moment for the Jews of Dallas, the mercantile class who started from scratch in this wide-open prairie town and have begun to build something of enduring value. Dallas is a place for free enterprise to prosper, if one has the instinct and the talent.

Edward Titche and Max Goettinger are speaking to Philip Sanger in the corner. These are important civic leaders, distinguished men of the community, and they act the part. Adolph Harris politely congratulates Simon and Joseph Linz. Alex Sanger, whose face is dominated by a bushy, walrus-like moustache, and who is perhaps the most powerful and influential merchant in the city, walks down the center aisle. E.M. Kahn, as always, stands out in the crowd, immaculate in a chocolate-brown suit; he sports a freshly-picked flower in the lapel of his coat, and holds an umbrella with an intricately carved handle. He wears the ring of a 33rd degree Mason.

On the roof garden, Victor Hexter – a small, slight man, who, peering through his rimless wire-frame glasses, looks like a small bird – sips sherry and discusses real estate with attorney David Eldridge and Texas Paper Company president Rudolph Liebman. The three men watch a train pull into the Santa Fe station a block or two away. From this height, the view is thrilling, even to gentlemen as cosmopolitan as these.

Sophisticated Dallasites continue to stream into the store. The mood is gay, the conversation sparkling. This occasion is a realization of the dream German Jews have been striving for since the earliest days of Dallas. And as dusk becomes night, as the patrons and guests and politicians and celebrities leave, as the nineteenth century becomes the twentieth, all seems well for the Jews of Dallas, particularly those – the Linzes, the Sangers, the Titches, the Goettingers, the Dreyfuss-es, the Kahns, the Reinhardts, the Harrises – who have put their names, placed their very identities, their entire lives, into stores for all the world to see. These are successful and enlightened people who will be the unchallenged leaders in the Jewish and non-Jewish communities of Dallas for decades to come. It is 1899, and it is only the beginning.

At the outset, then, came the German Jews. They came as pioneers along with everyone else, but with extra advantages. Edward Tillman, for example, brought along an M.A. and Ph.D. in chemistry from Heidelberg University, and with scholarship and entrepreneurial instincts made a fortune in the wholesale drug business. Like most of the Jews who came to America in the nineteenth century, the German Jews came to Dallas for a reason – to escape laws which restricted their freedom in the Old World.

They sought – as many immigrants in this period sought – economic opportunity, leaving small towns in Germany to arrive in small towns in America. They left Western Europe, just as the Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal had escaped the Inquisition and come to America almost a hundred years before.

They were special, these Jews who came to America from Germany. In all respects, they were the most cultivated and highly trained race in Europe, and they brought their considerable skills with them. Years later, another wave of Jewish immigration would arrive, only to find that the German Jews had established barriers against them. The later arrivals, streaming in from Eastern Europe and Russia, were the victims of Czarist ghettoes and religious pogroms. They would lack the sophistication and confidence of their German counterparts; for them, the Jewish experience would always be marked by fear. For decades to come, these two distinctly different roots of Judaism in America would grow apart in Dallas.

Most German Jews came to Galves-ton and, like the Linzes and Sangers, followed the railroad up from the Gulf, doing business in one small terminus town after another. In a few short years, enterprises were established in Dallas. By 1900, Sanger Brothers was one of the state’s great institutions and perhaps the single most important business in Dallas. In addition to retail and wholesale trade, Sanger’s provided banking services, financing other independent entrepreneurs. And the merchants were called upon to play different leadership roles: In 1907, for example, the city turned to Albert Linz to look after arrangements for one of the major events in early Dallas history – the visit of President William Howard Taft.

These were Jews who felt the need to re-form their Judaism, to form it again in an alien land, dropping those traditions and habits and customs which would hinder their ability to adjust to the New World. They found newer and freer definitions of Judaism.

In Dallas, they would contribute to the total community from the outset. They would become city councilmen, heads of the Chamber of Commerce, volunteer firemen, members of the school board. They – and their wives – would involve themselves in every area of public life; they knew it was good for their families, good for their businesses and good for their town. After all, they were among the most prominent Main Streeters.

In 1872, eleven men formed the He

brew Benevolent Association which later would develop into two organizations, the two most influential in the history of Dallas Jewry – Temple Emanu-El and the Jewish Welfare Federation. The mold was already cast for almost 75 years of undisturbed leadership. These families would exercise thé kind of judgment and civic aggressiveness which would earn Dallas Jews prestige and respect from the non-Jewish community. And these same families, in all but a strictly social sense, would assimilate and find themselves swimming in the mainstream of Dallas life. (From the beginning, though, socializing was restricted. The Columbian Club and the Dallas Country Club – one for Jews, the other for gentiles – were established by the turn of the century.)

The early German Jews were prag-matists, never denying their strong sense of Jewishness, but never seeing any conflict between that Jewishness and their responsibility as builders and pioneers in a small Texas town. Unlike the newly-immigrated Eastern European Jews who were settling the American coast in 1900, the Dallas Jewish leaders, by the time the Linz Building had opened its ornate doors, were already a fundamental part of the landscape here. Their memories of the Old World were nostalgic and positive. There is, for example, a remarkable account in the Beau Monde, the local society paper, from 1898, of a “Jahrmarkt,” “an exact reproduction of an annual fair held in a German village, [with] the costuming and staging and other features true to life – as those who have traveled in Germany will readily testify.” The paper called it “a credit not only to the Jewish people but to all the people of Dallas.”

The newer immigrants’ attitude toward the Old World was very different. No Eastern European Jew, living in Boston or New York, would dream of “recreating” the ghetto from which he or she fled, even to raise charity money. The memory of those ghettoes was far from merry. In fact, the ghettoes were being recreated in that part of the country, as the result of difficult housing and financial conditions. But in Dallas and throughout the South, German Jews were already civic leaders who viewed the established institutions with none of the fear and suspicion felt by Jews who had been persecuted in Russia.

The German Jews established a style of Judaism peculiar to the South: with its own abiding attachment to lost causes, the South was open and accommodating to a people whose whole identity as a race lay in ancient codes and half-remembered languages. The South demanded of the Jews only that they adapt to its quixotic ways; in return, it offered protection behind its veil of custom and courtesy. Here, in a defeated land where people cherished old wounds as medals of strange honor, a defeated race found a home. Occasional outbursts, when the South’s quixotic ways turned ugly, would disrupt the placid relationship. But even then, when directed toward the Jews, the South’s racism would be somewhat sheepish, as if their inclusion was obligatory and only done out of some perverse sense of fairness.

Those for whom the nightmares of the Eastern European pogroms were fresh would become the backbone of the Zionist movement in America, that political faction which insisted on the necessity of a Jewish homeland. If Jews away from the Eastern seaboard were inclined to assimilate and minimize the differences between themselves and their neighbors, thus eliminating those rituals which, in their minds, kept them from fully participating in civic life, the Eastern European Jews would emphasize the differences. They would be more radical in politics, more traditional in religion, more insistent upon the uniqueness of their ethnicity.

To the Southern Jew in Texas, life was open; influence and community involvement were more readily available. Society was as yet unstratified, and to be part of the establishment in these formative years – if you had the drive and the intelligence – was simply a matter of your own initiative. Alex Sanger served as president of the State Fair in 1894. Congregation Em-anu-El set up the first model for public education in the city. The Jewish sense of charity was strong, and the impact of the Jews far outweighed their numbers. In 1872, some 15 Jewish families lived here. Never more than three percent of Dallas would be Jewish and only a small percentage would assume leadership roles. But those names, at least through the early decades of this century, would be household words. It was a prairie town when they arrived. Within two decades it had been transformed into a bustling city. To a large extent the Jews were out front, creating the changes, leading the way, establishing themselves as an integral part of the phenomenal growth of Dallas.

II The Klan Marches

It is 8:55 p.m. on May 21, 1921, a warm and still Saturday night in Dallas. A Jewish family has decided to take a ride in the small family Ford. Saturday night in downtown Dallas, with the row of movie theaters brilliantly illuminated, with the streets alive and bustling with people, is always a pleasure. The father has endured a dreadful week and he wants to relax. Hired by the City Water Department in 1918 as an expert chemist on water purification, he has been suddenly fired. His release is a shock, but easily explained: the department has been taken over by the Ku Klux Klan, and it wants one of its own in the slot. A Jew will not do. So the Klan, which has also taken over a good deal of city and county government, has thrown the chemist out of work.

When the family, with their baby girl snuggled between them, reaches the Majestic Theatre, they are startled; the streets go dark and without warning men shrouded in white robes and hoods loom in the distance, marching towards them. The family freezes. They hear booming male voices singing “Onward Christian Soldiers!” They see the fire from a flaming cross. They see the men – there seems to be an army of them – moving closer and closer. They can make out the handwritten signs which declare “100 percent American!” “All Native Born!” “All Pure White!” “White Supremacy!” “Our Little Girls Must Be Protected!”

When the procession reaches the family, a Klansman in the crowd recognizes the father and blurts out, “Hey, what are you doing here?” No response is given, the family recalling recent stories of people who have been dragged from their homes and

whipped, in some instances tarred and feathered by the Klan. The long and frightening parade continues and as the torches pass they shine a strange light on the huddled family’s faces. Nothing happens. Perhaps it’s because the Klan doesn’t act in open and blatant ways. Perhaps it’s because the parade has distracted the hooded men away from the family.

The next day the Dallas News reports the incident in a front page headline: “KLAN MARCHES IN AWESOME PARADE.” The paper says 789 Klansmen participated, and that “it was a silent and serious-faced, wondering audience that greeted the weird procession.”

Since 1920, all had not been well within the small Jewish community which had built handsome homes on South Boulevard, on Park Row and on Forest Avenue. These people, for the most part successful citizens, had led their lives in relative calm and freedom. The closeness in the reform Jewish community had resulted in a good deal of marriage between families. In fact, in the early decades of the twentieth century, when a Dallas Jew with German ancestry referred to intermarriage, he or she was alluding to the marriage of a Western European Jew and an Eastern European Jew, or a reform Jew to a conservative or orthodox Jew.

Then the Klan came. And for reasons which are not difficult to understand – the Dallas frontier spirit which built business also fed the fires of vigilantism – the town became a haven for the Klan. In the half decade between 1920 and 1925, a Dallas mayor was said to have had Klan sympathies; the police chief was thought to be a Klansman; the district attorney was on the side of the KKK. And on the northwest corner of Main and Ak-ard stood Marvin’s Drugstore, run by a prominent and well-known Klansman, Z.E. Marvin. A high percentage of members of the police and fire departments actually joined the organization.

In this five-year period, it has been estimated that 13,000 Dallasites wore the robes of the Klan, perhaps the highest per capita ratio of any city in America. Hiram Wesley Evans, a Main Street dentist whose clientele was reported to be largely black, was first chosen as Exalted Cyclops and then, in November of 1922, at the Imperial Klanvocation in Atlanta, was annointed Imperial Wizard of the mighty Invisible Empire. That same year a Klan-supported candidate, Earle B. Mayfield, beat James E. Ferguson for the Texas Senate seat.

Earlier in the year, in March, Philip Rothblum, a Jew, had been taken from his home, blindfolded, whipped and told to leave town. It became a cause cèlèbre; the Klan admitted no guilt though there was suspicion that the sheriff and the police commissioner – themselves Klansmen – were covering up. Retail stores owned by Jews were periodically boycotted.

The fever spread and on October 26, 1923, the headline in the Dallas News reported “KLAN DAY AT THE FAIR: GREAT THRONGS PARTICIPATE IN COLORFUL KLAN INITIATION AT FAIR PARK.” The Klan had implanted itself so deeply into Dallas life – private and public – that the State Fair saw fit to designate a day in its honor. During the ceremony, J.D. Van Winkle, Cyclops of Dallas Klan No. 66, announced that the Klan was investing $80,000 in Hope Cottage, an institution for homeless children. Then Grand Titan Z.E. Marvin formally delivered Hope Cottage to the city. On the platform were civic dignitaries, including Mayor Louis Blaylock, Judge Felix D. Robertson (the Klan-supported candidate who finally lost the gubernatorial race in 1924 to Ma Ferguson) – and, of all people, Alex Sanger.

A Jew, the city’s most prominent Jew, sat on the podium with the leaders of an organization bitterly and unequivocally anti-Semitic. Looking back, it’s impossible not to ask if the German Jewish leanings toward assimilation and accommodation had brought men like Sanger to the point of actually aiding and comforting their enemies. No, but Jewish attitudes were complex.

First, many felt – as many old-timers feel now – that the Klan was basically a foolish and immature organization, a group of buffoons who created a tempest in a teapot. In the early days of the Klan, for example, John Rosenfield, easily identifiable as a Jew, covered Klan picnics for the Dallas News (where he would later become music and culture critic) and was left alone to do his work. Mayor Blay-lock who, unlike Mayor Sawnie Al-dredge, was associated with the Klan, often visited the homes of prominent Jews. Top Klansman Z.E. Marvin was said to think of banker Fred Florence as his good friend. So there was then, as there is now, much confusion about the very nature of the Klan. Was it a threat or wasn’t it?

In some deep sense Dallas Jews were afraid. There were simply too many Klansmen around to be ignored. As one gentile who sympathized with Jews during that period explained, the Klan was just the thing for young men on the make in Dallas. “The young bucks,” he said, “couldn’t resist. It was tough-minded, appealing and there was a certain male aura about the attitude which said ’let’s clean out the misfits and the foreigners.’ I fought it a bit in my mind, but I joined anyway. The Klan was a major force, at least for three or four years.”

As with many situations of this sort, ironies abounded. Louis Tobian tells the story of how the Dallas Dispatch wanted to reveal the names of people attending a Klan rally and did so by taking the license plate numbers of the cars seen at the meeting and tracing them to their owners. Tobian, a Jew, had sold his car the week before and apparently the new owner was at the rally. The paper reported that Tobian was in attendance. The next day he wrote a letter to the editor in which he claimed that the only clan to which he belonged was Dr. David Lefkowitz’s, the rabbi of Temple Em-anu-El.

In another incident, the Klan paid a visit to Edward Titche, the congenial head of Titche-Goettinger. They told Titche about the organization, what it stood for and why it was so important. Then they asked the department store executive to join. Amazed, Titche nonetheless carefully explained to his guests that he appreciated their time and interest, but membership would be quite impossible. He was Jewish. The Klansmen grabbed their hats and made for the door. “Too bad,” retorted one of the Klansmen over his shoulder, “you would have made a wonderful Kleagle.”

Still, the Klan was no laughing matter. Its growth here was unprecedented and, in the view of some, cancerous. While the Jewish merchants were silent, the reform community, represented by Dr. David Lefkowitz, was not. Together with George Banner-man Dealey, publisher of the News, and men like M.M. Crane, a local attorney, he took a strong and vocal public position deploring the illegality and basic anti-Americanism of the Klan.

Lefkowitz, a rabbi who was deeply committed to the notion of reform Judaism and to his responsibility in the community, had a powerful sense of his Jewishness. His radio broadcasts, like Levi Olan’s in the Fifties and Sixties, became legendary. He was part of an extraordinary tradition of reform rabbis, which included Dr. Henry Cohen from Galveston. (The famous Dr. Cohen story is one in which the Rabbi travels all the way from Galveston to Washington, D.C. and, after great difficulty, manages to meet personally with President Theodore Roosevelt to plead the case of an immigrant who is unfairly being deported. Roosevelt agrees to help and comments that Jews will do almost anything for one another. “Jews?” answers Cohen. “The man’s Greek Orthodox.”)

Lefkowitz followed another tradition, too, one Levi Olan calls “civil religion.” Like his two brother preachers – George Truett for the Baptists andBishop Lynch for the Catholics – hewas a minister to the entire community. These remarkable men werefriends, talked to groups together andformed a strange and untraditionaltriumvirate. Lynch would addressCatholics and non-Catholics alike;Truett would travel to speak to non-Baptist groups; Lefkowitz was foreverinvolving himself in non-Jewish causes. And it was this spirit of cooperation – the idea that everyone’s fate waslinked together – which brought ahappy end to the Klan episode.

Lefkowitz was a preacher who, though surrounded by fundamentalists, would not tolerate anything having to do with the Klan. In November, 1923, he wrote a friend in Tyler:

“I can’t answer your question concerning brother Alex Sanger sitting on the platform at the Hope Cottage dedication. You will have to come over and ask him; but don’t get too blue about it and don’t let the Klan situation worry you too much. It is bad enough, to be sure, but we mustn’t let it reduce our own power by worrying us and making us sick. We need the best we have to fight it to a finish.”

So Lefkowitz, together with Dealey, took on the Klan, no holds barred. The Dealey family had intermarried with Catholics and might have felt some kinship with the Jews. But more importantly, Dealey had deep convictions that the Klan was a lawless and pernicious outfit, and had to be run out of town. His unpopular stand cost the News circulation. (The Times Herald remained neutral.) In fact, in September, 1921, after the News carried an exposé of the Klan written by the New York World, sales dropped dramatically. (Circulation by the end of 1922 had fallen off by 3,000.) Even worse, ad sales were hit hard; some contend the News’ sale of the Galveston News to W.L. Moody, Jr. in 1923 was a direct result of its anti-Klan crusade. Certainly when the Galveston sale was made public, Klansmen rejoiced; they thought they had a chance of destroying Dealey’s fledgling newspaper empire.

In a letter to a Christian clergyman written in 1934, Dr. Lefkowitz describes how things had been:

“I am sorry to say that it [the Klan] got a good foot-hold and respectability through the fact that it had bored into the Masonic Lodge, especially in its upper reaches in the Scottish Rite. It was of course the mob spirit incarnate . . . You will pardon me if I tell you an incident in the course of which I believe I gave the death blow to the Klan in the Masonic fraternity. An election for the principal office in the Scottish Rite in this district was being held. A Klan member and a non-Klan Mason were opposing candidates. A tremendous assembly was in fever heat at the voting and the votes when counted showed that the non-Klan Mason had won by one vote. At this juncture, the presiding officer called upon me to speak. I made my appeal to the Klan and non-Klan in the well known thesis of good-will and fundamental religious attitudes. I described the blindness of Rabbi Michael Aronson and how he got it in the trenches in France, and asked whether he was a 100% American or not. Then I asked them, what would Christ do? The end of my address was marked by applause of Klansmen as well as non-Klansmen, the air had cleared and Masonry was on its way to kicking the Klan members totally out of its membership. From that time on, we had exceedingly little trouble from that group.

Perhaps the rabbi’s story ends on too self-contented a note; yet Lefkowitz and Dealey did, in fact, win. Their combined opposition was a blow from which the Klan could not recover. By the time Ma Ferguson beat Judge Felix Robertson, the Klan candidate from Dallas, for the governorship in 1924, the Klan was on its way out.

The KKK experience had a basic message for Dallas Jewry and particularly for the Dallas Jewish leadership which worshipped at Temple Emanu-El: by demonstrating the fact that he and the most powerful publisher in town had worked together, Dr. Lefkowitz had reinforced the conviction that assimilation, not ghettoization, was the key to survival. The rascals had been chased from town, and it was a Jew fighting alongside a non-Jew who helped get the job done. Simple cooperation, patience and the democratic way had won the day. Business could go on as usual. Jews could continue to participate in all aspects of Dallas. America, at least here on the frontier in the late Twenties, was keeping its promise.

III The Jewish President

It is 1929, a precarious year in American history. W.O. Connor – former treasurer of Sanger Brothers, member of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church and an influential Dallas businessman – takes a long, wistful look across the expansive ground floor lobby of his bank. He leans all the way back in his swivel chair and stares into space. He is president of the Republic National Bank, which has become a major institution in the region. Less than a decade ago, before the bank was nationalized, it had been called the Day and Night Guaranty Bank. And it literally stayed open days and nights to service and to court business. It was an aggressive, hustling little bank which hoped one day to stand toe-to-toe with the larger, more established First National. But that day will be for someone else; Connor knows he must step down.

His heir apparent is a young man from Alto, Texas. Fred Florence began in Rusk, Texas, by sweeping the floors of the local bank. In his twenties, he became the bank’s president and, by the time he reached 30, he had agreed to come to Dallas to become first vice-president of the Day and Night Guaranty. Connor had wanted Florence from the outset. In banking circles, whenever Florence’s name was mentioned, someone was sure to drop the word “genius.” At an astonishingly young age, he had developed a method for determining speculative loans on oil wells; he pushed the concept of car installment loans and construction loans; he was forever figuring out ways to lend money in order to get more money back. And he was a tremendously willing and energetic salesman. His life, his identity, his sense of destiny was tied up in banking.

There is no doubt about it, Connor thinks, watching customers stroll in and out of the bank. Still somewhat lost in his thoughts and reflections, Connor is convinced of the right move – Fred Florence will become president of the Republic National Bank, Fred Florence who has worked there for less than ten years, Fred Florence who literally began with nothing, Fred Florence who is a member in good standing of Temple Emanu-El.

A Jewish president in a non-Jewish bank; a Jewish president appointed by a non-Jewish board of directors. Although he was in this, as in many other ways, an exception and an enigma, no one typified the emerging American banker or the established Jewish leader more than Florence.

A Jew of Russian origin (his name had been changed), he had no problem entering the old-line Columbian Club social circle, just as he had no problem in breaking into the Christian banking community. Barriers were falling, and Florence was not to be denied. He taught himself what he needed to know, and when the city’s financial interest turned from agriculture to oil, Florence was waiting. He understood the times in which he lived. And he understood the obligations he had as a Jewish leader – to the community and to his fellow Jews.

He married the rabbi’s daughter and became active at the Temple. His downtown business activities were incredibly various; he believed the growth of his bank would be directly tied to the growth of his city. He was never mayor, but he didn’t need to be. With the engaging founder of Mercantile National, Bob Thornton, as a close friend, he was deeply involved in leadership decisions in the pre-war period which would shape Dallas into a major city. Thornton and Florence would begin each business morning with a long, intimate phone conversation with one another – solving credit problems for emerging new businesses, keeping tabs on the flow of funds, checking the progress of civic causes, and advising one another on appointments to key civic and political posts. In 1936, they brought the Centennial to Dallas. That worked so well that Thornton later came to Florence with a radical idea for formalizing civic leadership into a citizen’s council; Florence gave his approval, and the famous Dallas oligarchy was established. For the years that it reigned unchallenged over an increasingly prosperous city, their names were side by side at the apex of Dallas leadership.

Florence was an aloof man, conscious of his title and role and the need to maintain absolute dignity. He was said to have had a manicure and moustache trim every working morning of his life. He was orderly, persistent, determined to build the biggest bank in town. And he made it – invited to the White House by FDR, elected president of the American Bankers Association, friend of Jesse Jones of Houston and William Lewis Moody, Jr. of Galveston. Later, W.A. Criswell of the First Baptist Church of Dallas would speak of Florence as an intimate and cherished companion.

Herbert Marcus, Sr., Arthur Kramer, Sr., Henry Miller, Sr., Charles San-ger, Julius Pearlstone, Henri Brom-berg, Sr., Lawrence Pollock, Sr., Louis Tobian, Herbert Mallinson – these were the leaders in the Thirties and the Forties, the continuation of the tradition of the reform Jew as model citizen. Of course, members of other Dallas Jewish congregations, conservative and orthodox, the more traditional groups, also would produce leaders. But the giants were all more or less from that single constituency which had its roots deep in the tradition of Texas.

One of the great rivalries of this period was between Herbert Marcus and Arthur Kramer to see who could first persuade the Metropolitan Opera Company to plan yearly trips to Dallas. Allied with area leaders such as Edmund Polk of Corsicana, Kramer won; Marcus succeeded in coaxing the Chicago Civic Opera into visiting. Kramer, as head of A. Harris, and Marcus, who had left a salesman’s job at Sanger Brothers to establish Nei-man-Marcus, were of course interested in selling merchandise to an increasingly sophisticated city, a city concerned with dressing up for the finer things in life – such as opera. But they were also directly involved in the cultural life of Dallas. In the history of music here, the fine arts, the museums, the theater, the names of these families recur constantly.

The 5:30 social curfew would continue; after work a very fine but nonetheless apparent curtain separated Jew from gentile. The social distinctions and separations were definite. Most people remember only one Jew who has been a member of the Petroleum Club, and that was Fred Florence. (Even today certain institutions of Dallas society – the Idlewild, the Dallas Country Club, Brookhollow, Northwood and perhaps one or two others – have kept their doors closed to Jews.) But in the area of culture, non-Jewish Dallas knew well that it needed the support of Dallas Jewry, not only financial support, but the time commitment and taste required to build the arts here. For more than 40 years, it was John Rosenfield, the nephew of Arthur Kramer and the son of M.J. Rosenfield (who had been secretary-treasurer of Sanger Brothers) who ruled this region as cultural czar. His taste was unquestioned; he became the symbol of critical sophistication in the arts as the leading theater, ballet, opera, symphony and movie critic for the Dallas News.

IV

All Things to All People

Julius Schepps could never resist stopping off and chewing the fat at the fire station. After his family moved down from St. Louis, just at the turn of the century, he loved to wander into the old No. 2 Station at Commerce and Hawkins. Later, in South Dallas, his papa opened a bakery across from the No. 12 Station on South Ervay. In the early days Julius rode out on the trucks with the men, working along with them as they fought fires. In 1924 he was made Honorary Fire Chief by Tom Meyers, the real chief of the department.

Today the August heat has gotten to Julius a bit and he decides to leave his Canton Street office where he has been busy with the details of his wholesale liquor business. He slowly meanders toward Main Street, past City Hall to the fire station. Faces light up as Julius enters. Without a doubt, he is the Will Rogers of Dallas – as lovable as he is homely and awkward. He is tall and ungraceful in his movements. His face is craggy and thin, punctuated by enormous features, huge ears, kind eyes and a prominent nose.

Julius is everyone’s uncle, everyone’s country cousin. The firemen know that the next half-hour or so will be sheer pleasure – sitting around, shooting the breeze with this most charitable of men. Schepps is a legend around the fire department – a Jewish civic leader in a Baptist town, even though his livelihood is whiskey sales. Old-timers would tell stories not only about Julius’ generous side, but about his father as well. Mama Schepps, the story went, would have little Julius and brother George run down and get their father’s paycheck from him every Friday after work. If they didn’t catch their father in time, the bums would get to him and he’d give the money away – every penny of it. Those were the kind of folks Julius came from.

Julius loves to talk about being Jewish, about being Jewish in Dallas and about having so many wonderful Jewish and non-Jewish friends. But now it is 1940 and the events of Europe are very much on his mind. Today he wants to tell a story, down here at the fire station, about playing golf with some of his big-shot gentile friends at a fancy country club. He takes off his coat, hangs it on the back of an old-fashioned wooden clerk’s chair, swivels the chair around so that his long legs dangle from either side, rolls up his white shirt sleeves and spins the yarn:

“Y’all know, of course, that I ain’t the best golfer in the state, but then again, I ain’t the worst. And, well, so many of my good friends belong to that high class Dallas Country Club out there in Highland Park. They’re always asking me to go out and play with ’em. So last week I went on out and spent the whole afternoon chasing that little white ball from here to hell and back. Don’t want to tell you what I shot, but I’m not sure whether the final score had two digits in it or three. Anyways, we’re sitting around the club house and someone says to me, ’Julius, how come you don’t join the club?’ ’Fine idea there, pal,’ I reply, ’why don’t you run upstairs to the office and fetch me a membership application?’ ’Be happy to, Julius,’ my golfing buddy says. So he scoots out of the club house and goes to get me that application. And that, dear friends and neighbors, is one gent I haven’t heard from since. To this day, I’m still waiting for him to come back with the application.”

Julius Schepps was a folk hero who played a key conciliatory role in the Forties and Fifties, as Jews in Dallas began to see and feel enormous cracks in the foundation of their established leadership. Schepps was probably the last of the great Jewish leaders who could be all things to all people. His wife was not Jewish, but he belonged to every Jewish congregation in town, something which was not uncommon for prominent Jews here, though unheard of in other cities. Perhaps Schepps’ happiest hour had been when he led a fund-raising ceremony at Hope Cottage. He had reminded the audience that if they were to rip up the carpet, they would find the insignia of the Ku Klux Klan underneath, embedded in the floor. Those days are over, Schepps declared proudly. He saw himself as living proof of the fact.

But Schepps and millions of Jews like him across the nation had a new problem. It began in the Thirties with rumblings in Germany. Jews were forced to escape and had nowhere to go; America had not opened its doors. For the first time, the Jewish Welfare Federation had to focus on the problem of displaced persons, brothers and sisters in foreign lands who were homeless. Where were they to go?

To Palestine, the Zionists replied. To Israel. The wave of Zionism gained enormous strength as European Jews found themselves fleeing their native lands under the threat of certain extinction. The rhetoric was hot. Zionists felt that all Jews outside of Israel, living in what was called the Diaspora, must eventually come home. Of course many Jews, especially those of German origin, balked at the idea. The national Zionist movement did not find Dallas to be fertile territory. The Jewish leaders here were Texans, had been Texans and Southerners for more than a century. They were part of the land, part of the tradition; their loyalty was to the country and city which had enabled them to prosper. Israel was a remote idea, a foreign adventure.

Many from the reform community joined anti-Zionist organizations in the beginning. Support for Israel in the late Thirties and early Forties came from the more tradition-minded Jewish community – the conservative and orthodox congregations whose memberships, by and large, consisted of people with Eastern European backgrounds, Jews whose anxiety about anti-Semitism was reawakened. In 1939 and 1940, they saw the pogroms all over again. Jews would never be safe, they felt, until they had a national state of their own.

The fact of Israel would, once and for all, change the singular nature of Jewish leadership in Dallas. And yet Dallas would never undergo the trauma of other Southern communities – Houston, for example – where the Zionists and anti-Zionists never came to terms with one another. At some point, the old guard leadership – represented, perhaps, by Lawrence Pollock – would embrace the new leadership – represented, perhaps, by Jacob Feldman. Not that things would be the same; they would not. The German Jewish community would never involve themselves in Israel’s problems in the way, say, Feldman would. Feldman’s father was a deeply religious Jew, a traditional Jew, who had great conviction about the necessity of a homeland. Even when he made large sums of money in the international scrap iron business, Jake could never devote his entire life to his business. He had inherited his father’s visceral concern for Israel and would dedicate a large portion of his waking hours in the next 35 or 40 years to Israel’s cause.

The Feldmans, like the Pollocks, were a well established and highly respected Dallas family. It was not possible for the old leadership to scorn the Feldmans for their interest in Israel. These were not East Coasters; they were not immigrants, over-anxious in their fears about anti-Semitism. The Feldmans, and their opposite numbers – Leslie Jacobs who worked with Lawrence Pollock as executive vice president of the paper company, Reba Wadel who was a member of Temple Emanu-El – kept the community from bitterly dividing over the issue. Even Dr. Lefkowitz, who had initially joined an anti-Zionist group, could never set his heart against Israel. He wrote to a man in Cleburne in 1938 who apparently had written a letter to the News slighting Jewish settlers:

“Remember [the Jews] did enter into the Promised Land, Palestine, and make it a land flowing with milk and honey some three thousand years ago. And remember again, that when they were permitted. . . to return to a neglected and utterly ruined Palestine, they drained the marshes, built the roads, plowed, planted and milked cows, and again brought back fertility to the Holy Land. If that isn’t pioneering in the most arduous form, I would not know what is.”

History would not leave the Jews alone. And it would not leave the Dallas Jews alone. All too quickly what was happening in Germany became an inescapable fact: Hitler was attempting genocide. Millions had already been slaughtered. Millions more were scattered across Europe, fleeing, searching for a home, a refuge, a place to escape death. How bitterly anti-Zionist could anyone be at this point?

Meanwhile, in Dallas, Leland Du-pree, who serves as Fred Florence’s right-hand man at the Republic, receives an invitation to a fancy luncheon hosted by Tom Gooch, pub-Usher of the Herald, and Ted Dealey, publisher of the News. A few minutes before the event is to begin, Dupree wanders into the boss’ office to see if Florence wants to walk over to the hotel with him. Dupree, who is not Jewish, is shocked to learn that the bank’s president has not been invited. How is it possible? A big affair, at noon in downtown Dallas, sponsored by the two leading publishers in town, which does not include the city’s biggest banker? Dismayed, Dupree walks over to the Baker Hotel and finds not a single Jew at the luncheon. Later, he learns why: Gooch and Dealey, remembering Jewish contributions to civic causes, have decided to throw a luncheon for gentiles to raise money for strictly Jewish causes.

But if Hitler served to make those Jews who survived more Jewish, that transformation was most difficult for the Jews of the South who, at least in one sense, had as much in common with their gentile neighbors as with their brothers and sisters in Russia and Eastern Europe. Yet by 1948, the year Israel had beome an official state, this heightened consciousness of their Jewishness had already been developed. Jews in the South, Jews in Texas, Jews in Dallas were having to come to terms with themselves not as provincial Jews, but as universal Jews. And that represented an enormous change.

V The Rabbi Takes Charge

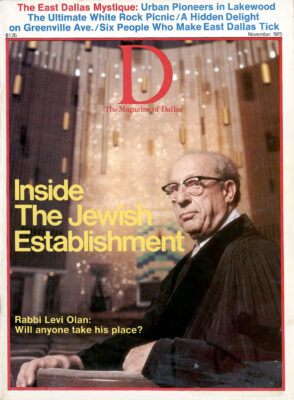

The final score is Rice 27, North Carolina 13, and as the two men gather their coats and hats and prepare to leave the Cotton Bowl on this New Year’s Day in 1950, the newcomer of the two looks around and wonders what his life and his future will be like in Dallas, Texas. He is a short man, with strong facial features, the kind of Jewish face which could be seen in a university, in a tailor shop, or in an orthodox synagogue. Levi Olan is, in fact, a reform rabbi who has just left Worcester, Massachusetts, to take over the pulpit at Temple Emanu-El. Just as David Lefkowitz had been recruited by Arthur Kramer and Herbert Marcus from Dayton, Ohio, in 1920, Olan had been signed up by representatives of that same line of Temple leadership – Louis Tobian, Irving Goldberg, Fred Florence, Lawrence Pollock and the man who has brought him to the game this first day in January, Eugene Solow. As the excited crowd, exhilarated by Rice’s victory, streams out of the stadium, Olan wonders what a liberal like himself will be able to accomplish in a conservative city like Dallas. He is an intellectual and a scholar who has been brought up in the East and whose background is Eastern European. The language in his home was Yiddish. He remembers that when he asked Rabbi Lefkowitz during an earlier visit where he could find good bagels in Dallas, the Rabbi replied, “What’s a bagel?” So here he is, at a college football game in the middle of the Texas prairie, a stranger recruited to be a leader.

When Rabbi Olan took charge at Emanu-El, the congregation was by far the largest in town. It still is, but in this twenty-five year period Dallas Jewry would witness a shift in its leadership for the first time since those eleven men came together in 1872. In many ways, Rabbi Olan’s period would be a glorious one for the Temple. As beloved and kind a pastor as David Lefkowitz was, he did not have Olan’s ability to inspire the congregation, and for that matter inspire the city, with bookish fire and brimstone. Like a black gospel preacher, Olan could shout with the best of them. His rhetorical gifts were rare; at once, he elevated, impressed, intimidated, shamed, scolded, forgave and motivated. He was a testifier, a witness, whose carefully written sermons – some of them took 20 hours to write – could shake the most complacent listener. His was a voice which could evoke the memory of thunder from ancient mountains.

Lefkowitz, for whom the new rabbi had warm and grateful feelings, had been on the radio for years. Olan immediately stepped into the role, first on KRLD radio and soon afterwards on WFAA-TV. By 1951, he was already a media star; hundreds of Christians today recall driving to church on Sunday morning while listening to Rabbi Olan preach at them through the car radio. He was an instant hit. His learning was appreciated. Dallas had never been audience to a clergyman with Olan’s combined talent for intellectual and rhetorical showmanship. He pointed a sharp finger at what was morally wrong with the city, but he did so in an acceptable way. He spoke for God and, given that, who could argue? A typical Olan statement, for example, is in a letter he wrote to a woman in Massachusetts in 1959 about segregation. She wants to know his position:

“The moral issue from my point of view is a clear one, segregation is a vestige of slavery, and is highly immoral. No one who believes in one God can believe in discrimination amongst His children. This is the position which any religious person must take.”

In his didactic way, Olan puts the case to rest. One is afraid to think that any other position is possible. And, in his more fiery and extravagant sermons, he might drop as many as 40 or 50 names – Kafka, Malraux, Tillich, Tolstoy, Faulkner, Spinoza, Sartre, de Tocqueville, Cardinal Newman – sending your poor mind reeling, taking your breath away. He was an Old Testament prophet, a consummate performer, with substance and clarity at the base.

Olan became such a strong and dominant religious leader in Dallas that by force of personality he would keep the Temple Emanu-El leadership tradition going 10 or 15 years longer than it might have without him. The rabbi was the hand-picked choice of the old guard, whose origins were in the earliest days of Dallas Jewry. Yet, as a man, as a Jew, he was unmistakably from another tradition. He spoke in lovely Old World Jewish expressions, with a Jewish cadence. And, from the start, the old guard saw that it didn’t matter. 1950 was a time of great change. Jews from the Eastern seaboard had been stationed here during the war, and many had stayed. Some Temple members were worried about the influx: they were concerned about the emphasis on ethnicity or on Israel, and during a Jewish holiday, one member of the congregation complained that children in Sunday school were being taught to wrap presents in colors of blue and white, the colors of the Israeli flag. “We’re being taken over by another wave of immigration,” he exclaimed, meaning those immigrant Jews who had passed through Ellis Island from Eastern Europe in the early part of the century.

Olan, however, like Lefkowitz before him, relaxed those tensions. Being ethnic, being Eastern, being able to joke in Yiddish – something which he claimed almost no one else in his congregation could do – hardly made any difference. He was respected as a philosopher and rabbi, both by his own members and his thousands of radio and television followers. Who could ask for anything more? Even if some found him cold as a person, and not the pastor Lefkowitz had been, his intellectual prowess more than compensated for it. Besides, Olan liked the oligarchy which ran the Temple. He found Fred Florence, Lawrence Pollock, Irving Goldberg, Jerome Cross-man and Louis Tobian to be men with whom he was temperamentally compatible. This was one of his many paradoxes: at heart, the rabbi has always been a democratic socialist who finds notions such as the profit motive unacceptable in his ethical structure. Still, he had tremendous admiration for these entrepreneurs, these capitalists who had sought him out. He would lunch with one or two of them at the Dallas Club, and he would find them agreeable to hiring a highly creative music director or an innovative religious school director. They understood that the rabbi was building an institution and was interested, as they had been in their own businesses, in reaching the entire town. It was a superb meeting of the minds and, in this paradoxical way, Levi Olan, old-time liberal from New York, Eastern intellectual and academic scholar, got along splendidly with those gentlemen who were such staunch defenders of the free enterprise system.

Olan was able to restore older traditions to what had been a leading reform congregation. During his time, the Bar Mitzvah was emphasized as it had not been in the past; more Hebrew was read during services. Christians would be encouraged to attend lectures in order to know the source of their religion. And on social matters, his civil rights stance, his involvement with problems of poverty and housing were so obviously sincere and so rooted in his sense of morality, that even in one of Dallas’ most conservative periods – the Fifties – his reputation continued to grow as his name spread to virtually every part of the city.

VI A House Divided

Bernard Schaenen, a member of the conservative synagogue Shearith Israel and brother-in-law to Jacob Feld-man, is worried. He is president of the Jewish Welfare Federation this year, the year Adlai Stevenson is making noises about running against Ike again. It’s 1956, an uncomfortable, humid April, and here in the large den of a North Dallas home, tempers have begun to flare.

Schaenen recognizes that his presidency represents a change. In the past, the Federation leaders have more or less paralleled the Temple leaders, the same people who spoke for and to the Jewish community. Now there’s a difference. Jews from the conservative and orthodox congregations are stepping forward and taking an aggressive lead in Jewish matters in Dallas. They are openly concerned about Israel. And now, in this late-night meeting with a cross-section of leaders – rabbis, congregation presidents, professional fund-raisers – it seems as though no solution will be reached on one point: what’s to become of the plans to build a Jewish Community Center?

Some old guard Jews feel as though the long-standing tradition in Dallas of an open community, in which Jew and Christian play and work and live together, is being threatened by the establishment of a strictly Jewish center. “Is there any such thing as Jewish basketball?” someone shouts. People in the conservative camp are convinced that Jewish kids need a place to congregate and learn after school. A woman asks, “Are you ashamed of being Jewish? Why shouldn’t we have a place of our own?” “It’s ghettoiza-tion,” a young man replies. “It’s the kind of segregation we’ve been arguing against as applied to blacks. Why impose it on ourselves?”

So the argument rages on: open community vs. closed community. Total assimilation vs. a center to maintain identity. Some see the center as an attack on the legitimate functions of the synagogues and the temple. The more conservative rabbis want the center built, but closed all day Saturday to honor the Sabbath. Some rabbis don’t want the place built at all. Some in-between reluctantly agree to a center, but one which will be available to the entire community. Finally, a compromise is struck by Jack Kravitz, the professional who runs the Federation: a center will be built, but it will not be “Jewish,” it will be named after a man who is present at this very meeting, Julius Schepps. Fifteen percent of the membership will be reserved for non-Jews.

The participants are half-asleep and happy to go home. By now it’s nearly 3 a.m. As they walk to their cars, each wonders privately how deeply this division runs, what consequences it holds for Jews living in Dallas. Something very new is under way.

The Fifties was a troublesome period for Dallas Jews. During those years – the McCarthy years – Jews felt particularly vulnerable. And at SMU, a university which had benefited from local Jewish generosity for decades, there erupted a nasty little incident known as the Beaty Affair.

Dr. John O. Beaty, professor of English at SMU and at one time department chairman, had written a viciously anti-Semitic book called Iron Curtain Over America. A tenured professor, Beaty never was fired by the university, and many Jews argued that he should not have been; after all, it was a matter of academic freedom. But his blatant anti-Jewishness became such an established fact, that often Jews would go far out of their way to avoid his courses.

While Jews were uncertain what the overall community thought of them and what they thought of themselves, the reform Jews built a dignified new sanctuary in the heart of North Dallas.

Temple Emanu-El moved to the corner of Hillcrest and Northwest Highway, to an expansive and impressive edifice which symbolized the strength and dignity of the reform community. But as that move was under way, in fact on the very day the ground for the sanctuary was broken – June 5, 1955 – Dr. David Lefkowitz died. The world for Dallas Jews was turning at a faster rate than ever before; weekly now, Olan was preaching against the immorality of segregation, of wealthy people who live in fancy highrises and ignore the needs of the poor. Meanwhile, tensions were mounting at Hillcrest High School where the standard joke had become, “All gentiles will meet at 3 p.m. – in the first floor phone booth.” Some Jews were nervous about a sense of too singular, too strident an identification; others were nervous about too weak, too diluted an identification.

In the process of raising money for Israel, it became obvious that an economic shift had taken place. Conservative Jews, Jews of Eastern European origins, had begun to make fortunes of their own. And in many cases, the money made in the Forties, Fifties and Sixties far exceeded estates built by the earlier generation of reform Jews. Businesses with international connections were growing here. And though the heads of those firms might be active members of Temple Emanu-El, as was the case with some of the Zales, or the Levys of National Chemsearch, their sentiments were strongly pro-Israel. They gave money in amounts the old guard would have never thought possible. And there was also a dramatic increase in travel to Israel. Dallas Jews, returning from those trips, often felt great inspiration and further dedication to the cause.

Members of the old guard still had a visceral fear of closing the community and breaking ties with the Christian leadership. Why put our wagons in a circle and enclose ourselves, they wondered. While the Schepps Center floundered because reform Jews refused to embrace it, the new guard had its foot in the door. The tide of Jewish ethnicity was on the rise. It would take another twenty years – until 1975 rolled around – to get the center off the ground, change its name from Schepps (which would become a wing in the new complex) to Jewish Community Center.

The Main Streeters by now are gone, in fact have been gone for decades. The stores they built sold out – all of them – Sanger’s and Neiman’s, Kahn’s and Dreyfuss and Linz. With them, many of the downtown merchants who had a vested stake in the city and its future are gone. Rotating managers, sent from New York or Chicago, move in and out of town like customers walking through revolving doors. A different kind of downtown leadership emerges, and no longer does anyone know or care whose origins are Eastern or Western European.

Throughout this period, the Jewish Welfare Federation – the central fund-raising organization for basically Jewish causes – grows in strength and importance, more and more looking to the conservatives for leadership. The monetary needs of Israel become enormous. The practical job of raising first one or two, then three or four, and finally six or seven million dollars in one year necessitates a professional group which must turn to those men and women willing to roll up their sleeves and go after the contributions. To do so requires a heartfelt and emotional commitment to the state of Israel, the sort of commitment personified by a man like Jacob Feldman. In the old days, the Thirties or early Forties, the yearly goal might be $70,000 or $100,000. And typically the Federation president would be the same man who had been a year before, or who would be a year after, president of Temple Emanu-El. No longer, though, is that true. Leadership slowly starts to democratize, to spread out over the community and find itself in the hands of people (many of whom are not native born) who lack a name in the general community or long-time standing among reform Jews.

VII “You Don’t Have to be Jewish…”

On Sunday, June 11, 1967, thousands of Dallasites are turning the pages of the Dallas News and thousands are drawn to an extraordinary ad which has been paid for and signed by Neiman-Marcus. The headline reads: “YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE JEWISH TO HELP THE PEOPLE OF ISRAEL.” The author of the ad, Stanley Marcus, is probably not aware of the irony in the copy which he has written. The Six Day War is over and Marcus, who was raised a Jew but never practiced the religion, feels for the first time in decades a sense of his Jewishness. Egypt has attempted to drive Israel into the sea and it hasbeen stopped. The victory is glorious: Jews everywhere feel an exuberance and pride and resurgence of identity.

Later on this same afternoon, in a motel adjacent to Love Field, a group of national fund-raisers from New York are meeting with Jack Kravitz, the Dallas Jewish Welfare professional, and a number of hand-picked sympathizers with the Israeli cause. In the aftermath of the war, they are told, the financial requirements are staggering. The group listens intensely. After the meeting, they respond. Among themselves and others, they will raise three and one-half million dollars for social services in Israel – all within 24 hours.

It is impossible to overstate the impact of the Six Day War. Jews came charging out of the closet, giving, caring, committing themselves as never before. Even the staunchest anti-Zionists from days long gone by, those who opposed the formation of the state and saw it in conflict with other allegiances, could not resist the sense of triumph and relief which the war provided. Olan himself, never an emotional and intellectual enthusiast for Israel, now joined the fold. The rabbi was shocked that many of his fellow preachers and theologians on the Christian side remained, as he puts it, “shamefully silent” on the question. Where is their support, he wondered. He wrote an essay that begins, “It became clear during the Israel crisis of June 1967 that the Christian-Jewish dialogue has been a dismal failure. The Church in its organized structures was at best neutral, and at worst antagonistic, during Israel’s struggle to survive.”

The reform community, aside from certain families, has been long in catching up, but by 1967 the new day has arrived. Ethnicity is here to stay. The blacks are beginning to be more black; the Mexican-Americans more Mexican-American. It’s all right to proclaim your racial pride, to stress the difference and not the similarity.

The idea of an oligarchy is no longer palatable. The disintegration of the oligarchy in the Jewish community is no different from that in the overall city. Waves of new Jewish citizens have washed over Dallas, people who have never heard of the founding fathers. The names are no longer magic. The notion of a leadership establishment is no longer possible. There are too many various interests, too much stress in too many areas. In the Jewish community new faces appear, people willing to raise money for Israel, people anxious to build a new Community Center. The Federation takes the place of Temple Emanu-El as the central institution of Jewish life in Dallas. And even the Federation, with all its influence, cannot speak for all Jews. There is dissent about Jewish education, dissent about how much charity should be directed toward the non-Jewish community, dissent about how much money should be directed toward Israel. A marked increase in conservative and orthodox Judaism among young people signals their search for a more clear and tangible sense of identity. The Yom Kippur War in 1973, with its alarming beginning and bitter end, causes more uncertainty about the precariousness of Israel, more determination on the part of Dallas Jewry to make certain the state will survive.

It’s always been easier for Jews to define themselves negatively rather than positively. In the face of adversity, Jews often respond with great courage and wisdom. But without that threat, without that struggle, the bonds loosen. Perhaps that’s one reason Israel has become such a rallying point. That small and beleaguered state has come to represent a culmination of the total history of Jewish persecution and strife. Jews have less need to struggle in America and in Dallas for equality and recognition. A niche has already been carved here. So the energy, the attention, the anxiety is focused on Israel.

Jews in Dallas have made immeasurable contributions to the city’s development. They have done so, for the most part, unselfishly, giving of themselves in great disproportion to their numbers. Jews in Dallas have never held great power or, in relation to the overall economy, great wealth. They have had some political influence, some economic influence, but nothing to compare to the way Jews have far-reaching effects on the communities of New York, Philadelphia or Chicago. Here Jews were, and Jews remain, small in number and, though in some ways atypical, a microcosm of the larger community. While some organizations like the National Council of Jewish Women continue to spend the vast amount of their time on non-Jewish social service work, other groups explore a heightened sense of their ethnicity or involve themselves with the urgent problems in Israel. And like the rest of Dallas, Jews are struggling with the present, looking for roots, trying to understand who they are and what they want to become.

VIII The Rabbi at 72

It is the summer of 1975, and the August heat is nearing 100. A writer walks across the deserted SMU campus to the Perkins School of Theology and enters the Bridwell Library, a small, modest building, perhaps the single loveliest part of the campus. He passes under the curved staircase which winds its way down from the second floor, behind the book-return desk, back past a quiet reading room sparsely populated by serious students lost in their books of religious learning. He takes an elevator to the second floor and wanders up and down the aisles, through the stacks, peeping into the tiny carrels in which still more students are buried in their work. Finally, he reaches his destination. Sitting there, intensely leaning over a small desk littered with essays and magazines, is Levi Olan. His grey wash-and-wear raincoat hangs on a hook behind him. He’s wearing a pair of old trousers and a short-sleeve sport shirt. One might mistake him for an ordinary working man. But there can be no mistake – he has returned to the life he loves best, the life of a student.

He greets the writer, whom he knew as a confirmation student some 16 years ago, with warmth and affection. The rabbi looks old and tired; he is 72. “I have no office,” he apologizes, “but we can go talk in the Bishop’s Room. I have the key.” So the two of them walk back through the stacks and into a long, narrow room which contains an enormous conference table. They sit at the far end of the table, in chairs next to one another, and chat and argue and renew their acquaintance.

As the hours pass the writer learns that Olan remains committed to the notion of democratic socialism, thinks the world is being ruined by the corporations, being run by smaller and smaller men. Although the rabbi has contempt for corporate life in America and all its implications, he still admires those men whom he knew in the early days as founders of such organizations, men with whom he worked and lived and cooperated for over 20 years. Those men are gone, he says, in a voice which sounds very lonely, and he sees no one to replace them. A ce-lebrator of democracy, he seems unhappy living with the consequences of democracy. An antagonist to concentrated power, he seems depressed at the loss of autocratic leadership. Still, each day he reads from 8:30 in the morning till 2 in the afternoon. He is writing books and essays, and he is happy to be retired. His contribution was made, he feels, though he is no longer entirely comfortable in the world of 1975. He reads Vonnegut, Heller, Pynchon and the rest. He worries about Israel more. He thinks, he feels, he is certain that almost everyone has sold out, that the old Christian and Jewish leadership is gone.

The rabbi picks himself up and slowly walks to the window which overlooks the campus of the Methodist university where he has now taught for decades. He squints as he focuses on something outside, talking all the while, discussing the nuclear age, electronic music in New York, fund-raising bureaucrats and the strange politics of Henry Kissinger. The writer senses that its time to excuse himself and leave the rabbi to his studies.

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

Dallas College is Celebrating Student Work for Arts Month

The school will be providing students from a variety of programs a platform to share their work during its inaugural Design Week and a photography showcase at the Hilton Anatole.

By Austin Zook

Basketball

A Review of Some of the Shoes (And Performances) in Mavs-Clippers Game 1

An excuse to work out some feelings.

By Zac Crain

Home & Garden

Past in Present—A Professional Organizer Shows You How To Let Go

A guide to taming emotional clutter.

By Jessica Otte