The first inkling of James J. Ling’s most recent adversity came in late May, when he sued Touche, Ross & Co. and Hertz, Herson & Co. for a cool $115 million.

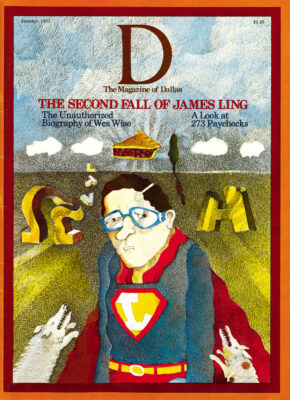

We already knew that Omega-Alpha, Inc., was in trouble, bad trouble. The press releases told us that. Several millions of dollars in secured bank debt in arrears. The trading of its stock suspended temporarily. Other debt coming due, and no funds to make even the interest payments. Each time a new dollop of bad news developed, Senior Vice President Richard L. Thomas issued another gloomy press release. So we knew, just by reading the business pages, that Ling was, again, Underdog. We could have been forgiven for wondering if, maybe, he didn’t really enjoy the role. He has played it so often.

But for most of us addicted Ling watchers, there was every expectation that he would pull out of it with a flourish, Sopwith Camel style. We thought he would pull out of it until we read the pleading filed in the Southern District Court of New York, the one seeking $115 million from two of the nation’s largest accounting firms. Cough! The pleading was unbelievable. It was as though Our Hero, Our Favorite Financial Genius, the bloodied but undaunted victim of the LTV hijacking of 1970, had bought himself the Brooklyn Bridge.

The “Brooklyn Bridge” in this case was a New York company called Transcontinental Investing Corp. Ling had purchased it in March, 1972. He had paid $51.3 million for it, with the idea that he could shore up its sagging fortunes, split the company’s various subsidiaries into autonomous companies and sell them off separately. It was an old Ling ploy; corporate strategists call it “redeployment.”

Claims Assets Missing

But TIC, Ling’s suit against the accounting firms contended, had turned out to be un-redeployable. By Ling’s accounting, he had flatly been sold a rotten hulk, a bill of goods, a gouty albatross. Many of the assets listed by TIC executives and their two New York auditing firms couldn’t be found, Ling charged. The company’s units, primarily a home mortgage firm, headquartered in Atlanta, and a phonograph record and music tape jobber, weren’t nearly so profitable as claimed. As a denouement, Omega-Alpha wanted the court to award it $65 million in actual damages and $50 million in exemplary damages from the auditing companies, allegedly guilty of “false statements, omissions and misrepresentations.”

With the filing of the New York suit, a cathartic mood seemed temporarily to overtake the offices of Omega-Alpha on the 31st floor of the LTV Tower. Now, at least from the company’s view, the truth was out. No longer did the Omega-Alpha executives have to reach for medicated throat lozenges when asked about the reasons for their tribulations. The filing of the suit was their mea culpa. They had, in this case, come clean. Now, in the aftermath, they could even afford the luxury of a little righteous indignation.

“The TIC thing is one of the biggest damned messes I’ve ever seen and ever will see,” a junior Omega-Alpha executive said one afternoon shortly after the suit was filed. “We found six warehouse rooms filled from floor to ceiling with unreconcilable paper. Accounts that dated back three, four, five years.”

A few days later, the Omega-Alpha chairman himself became available for a few moments. “We were simply deceived by the financial statements,” said James J. Ling, trim and fit at age 51. “We were aware that Transcontinental was having financial problems. But on the other hand, we were furnished with a balance sheet which specified that the company had ’x’ number of dollars in assets and that it had turned around. It simply was not true. It had not turned around.”

He said some other quotable things about Omega-Alpha’s executives being knowledgeable and sophisticated businessmen. But then, he added, so were the people who were taken to the cleaners in the Equity Funding scandal (one of the great Wall Street fiascos). Omega-Alpha had simply been caught in a financial sandtrap. It was embarrassing, especially for him. But he took full responsibility for it. “It’s just that simple,” Ling said, looking at his watch. “It was a tremendous mistake, and I’m not trying to justify it.” But he had always learned from his mistakes, he said. While some of the New York financial community were giving odds of 1,000 to 1 for Omega-Alpha’s failure, Ling preferred to remain philosophical. “I know what I know,” he affirmed vaguely.

Later on, Ling’s staff talked him out of using that “I know what I know” stuff. It sounded too Delphian for quotation in the Wall Street Journal and Business Week, and it sounded too amorphous for stockholders interested in full disclosure.

We talked briefly about other matters. Mainly, I was interested in his “game plan” for survival. Just how was it that he proposed to refloat a company floundering under losses of $115 million, a net worth deficit at March 31 of $45.8 million, a working capital deficit of $21.3 million, and a negative cash flow? For the second time in perhaps a 15-minute period, Ling impatiently dismissed the question with an intercom call to his secretary. The first time she had arrived with a totally inscrutable two-page Xeroxed sheet titled “Comments/Facts Relative to Transactions involving NAAC/TIC/TMC/Chase/O-A/NAAC-Ownership of SMI-1,500,000 Shs. Total,” and Ling had proceeded to make a point, however unintelligible. This time, she returned with a 107-page amended preliminary copy of an explanatory statement to some of Omega-Alpha’s subordinated debenture holders. This would explain his game plan, Ling said blithely.

The Plan and the Players

In typical Lingian fashion, he was intent on pulling off a series of events that were audacious. One deal fitted into another, like gears in a sophisticated transmission, until about 12 of the pesky little cog-cepts were required to be present for the whole thing to work. One obstinate party could be a wrecker of the whole, if he should take his gear and go home.

Joseph Drennan, for example, could do it. Drennan was Ling’s banker, a vice president for First Pennsylvania Banking and Trust Co. With two other Eastern banks, First Pennsy had loaned Omega-Alpha $25 million a while back; it was getting to be repayment time. A $10 million payment had come due last December, and Ling had missed it. Since the $34 million assets of Omega-Alpha’s prime subsidiary, the cable-manufacturing Oko-nite Co., were pledged as collateral, the banks had felt comfortable letting the payment slide for the moment. The banks agreed to let Ling wait until June 30th, when the $10 million plus another $5 million would be due.

Assigning Priorities

The holders of two of Omega-Alpha’s convertible subordinated debenture issues could also play the spoiler. Over a million dollars in interest were owed to these shareholders on June 1 (on 22 million shares of 4% percent debentures due 1992) and July 15 (on 26 million shares of 6 1/2 percent debentures due 1988). Even if he could get the cash – he wasn’t sure that he could – Ling didn’t want to use it to pay interest on subordinated debt; there were other, more desperate, needs. So he had proposed a one year debt moratorium, until June 1, 1975. And to put some bite into his importuning bark, he warned the shareholders that a refusal of the moratorium could very well put Omega-Alpha into bankruptcy.

Ironically, Ling’s old company, LTV Corp., was also knocking at the door. Ling had bought Okonite from LTV in 1971, and the two Ling-spawned companies were now feuding over some obscure, million-dollar clause having to do with a convertible debenture exchange. LTV contended Omega-Alpha owed it several million in stock and about $140,000 in cash, and to emphasize the point, W. Paul Thayer’s LTV had filed suit against Omega-Alpha in March. The suit sought to keep Ling from selling assets that might be available to Omega-Alpha’s creditors.

The asset that LTV particularly had in mind was General Felt Industries, Inc. The New Jersey-based carpet underlay manufacturer was Omega-Alpha’s other main subsidiary, and Ling desperately needed to peddle the company. He needed the cash from the deal to bring payments up to date at First Pennsy.

Speaking of General Felt Industries brings Marshall S. Cogan into the picture. Cogan, too, though unwillingly, could also thwart Jim Ling’s game plan. Cogan was a New York investment banker and, until a few months previously, had been a director of Omega-Alpha. Seeing that Ling couldn’t find a decent buyer for General Felt, Cogan had resigned, formed a company called MC Corp., obtained financial backing, and agreed to buy General Felt himself. Should he falter now, the ballgame would almost certainly be over.

In the shadows, there were also a gaggle of supernumeraries. Since they, too, could queer the deal, they were really more than mere bit players. The Justice Department was one. Also, a couple of courts were involved at one point or another, which meant that any agreement-in-the-round reached by all of the major parties had to pass some faceless judge’s scrutiny on an issue minor in the overriding concern, Omega-Alpha’s survival. Also, a court-appointed receiver in Atlanta was under withering fire to do something, anything, by people of modest means in Georgia who had lost money in the TIC-connected home mortgage company Omega-Alpha no longer owned. Unfortunately, Ling still owed the bankrupt Atlanta company $9 million, which he couldn’t pay.

In late June, the Omega-Alpha staff was frantically busy on a number of fronts. The most important were (1) getting the debt moratorium approved by debenture holders and, (2) reaching a settlement with LTV on the debenture exchange problem.

The negotiations with LTV remain one of the least illuminated aspects of Omega-Alpha’s Summer of Travail. Although a suggestion of mystery exists, one suspects the LTV legal staff made a serious error in February negotiations with Omega-Alpha and, in effect, legally released Ling from several million dollars in obligations. Later, LTV tried to reverse itself, but Omega-Alpha, understandably, insisted on the February agreement.

It wasn’t until July 12, a Friday, that a tentative agreement was forwarded to the LTV board of directors for approval. Its terms, as later announced, tended to support the theory that LTV had signed an agreement in February that it later regretted. Omega-Alpha would pay only $5.2 million in securities against a claim by LTV of $17.8 million.

That same Friday, there was a palpable upturn in spirit around the Omega-Alpha offices. Finally, the players in this high-stakes monopoly game could do something. That very weekend, Rich Thomas, the senior vice president; George Guynes Jr., the corporate counsel; J. T. Ling, the assistant to the chairman (and the chairman’s son), plus attorneys from Omega-Alpha’s law firm, Wynne Jaffe & Tinsley, were heading for New York’s Lombardi Hotel. There, in smoke-filled conference rooms, they were to hammer out the solution to Omega-Alpha’s very critical debt problems.

“We’ve got eight sets of attorneys and several hundred documents, all relating to the other,” said an ebullient J. T. Ling, a St. Mark’s exe, who for a time acted as a genial and candid Omega-Alpha spokesman. (Later, he felt himself “burned” on a couple of comments, and he subsequently demurred when reporters called him.) “We are fairly bullish at this point.”

Black Knight Comes Riding

There were other reasons for J. T.’s exuberance. On the previous Wednesday, in another of those typically Lingian maneuvers, the Omega-Alpha chairman had announced that the company might have a buyer. The news was electrifying to the staff, since no one knew in advance. Ling had carefully conducted secret negotiations with New York industrialist A. R. Gale. Ling had met Gale only once before, and then only casually, but the chairman was captivated by Gale’s proposal. Ling would later call Gale’s offer to take an option on a $12 million package of Omega-Alpha securities a “brilliant insight” and an “excellent job of analysis.” Gale’s option was slated to expire on July 24.

It did expire. The reasons remain in dispute. A press release issued by Omega-Alpha on July 25 claimed that Gale had been victim of the shaky international business picture and couldn’t get the financing. But Gale himself would insist that it was mostly Ling’s doing, that the chairman of Omega-Alpha was inhospitable toward a deal, especially since Gale wanted Ling removed from the picture. “After the sale of General Felt, Ling thought that he could pull off Omega-Alpha’s survival himself,” Gale told one inquirer.

Making the Pieces Fit

The sale of General Felt to Marshall Cogan and his MC Corp. had been accomplished in the tough, detailed conferences at the Lombardi Hotel. On the surface at least, it appeared that Ling’s dominoes were falling into place. With the help of the $11.4 million in cash from the sale of General Felt, Ling could make a substantial payment on his $15 million debt to the Eastern banks. With the LTV settlement, Omega-Alpha stood to gain millions, provided the Justice Department and the courts approved. Omega-Alpha had also settled on another $2.1 million in debentures for approximately 30 cents on the dollar, and Ling said he now had a way to pay the interest that had been due June 1 and July 15 on the two big subordinated issues.

Not long after that, I again was ushered in for a few minutes with Ling. In the interim, the chairman had changed offices. Movers had loaded Omega-Alpha’s 56 filing cabinets, ten desks, conference table, Xerox machine and Ling’s fragile, hand-carved Venetian chess set and carted everything down one level – to the 30th floor of the LTV Tower. It was an economy move. It would save embattled Omega-Alpha $42,000 a year, the difference in paying for a suite of 10,000 square feet and one of 4,000.

The interview, as before, was remarkably scattershot, with never more than a few sentences on the same subject. Ling spoke of Gale, the would-be buyer, explained that the Bank of America was Okonite’s lead bank, recalled how he first met Marshall Cogan, insisted that press speculation that he harbored a dream of retaking LTV (“It is not a practical aspiration”) was scuttlebutt, and explained why Omega-Alpha had only three directors. Then he turned philosophical, and it was at this point that a different James J. Ling, a mellower one, a wiser one perhaps, took the podium away from James J. Ling, hard-knuckled conglomerator.

There was nothing in his business background, he explained, to prepare him for the problems he had faced with Omega-Alpha. “We had a little experience in this sort of thing in 1962 when we were merging Ling-Temco with Chance Vought,” he mused, slumped down in a chair at the end of his conference table. “But this is on a much grander scale.” He said he had learned a lot, and that he would benefit from it. It had been too long, he continued, since he’d had a vacation (three years), but he intimated that one was in the offing. Ninety-nine per cent of the time he slept well, and his health was great. It didn’t matter that his salary was down to $95,000 from the $375,000 a year he made at LTV. “My wife gets the checks anyway,” he chuckled.

He walked over to the chess set that Troy Post (remember Troy Post?) had ordered specially made in Venice while the two of them were negotiating for LTV’s acquisition of Greatamerica. “To see ahead to the 16th or the 17th or the 18th move is a tremendous accomplishment,” he said. “It’s just too much for most people to think about.” For a moment it seemed he was talking about chess, but he wasn’t. He was talking about Omega-Alpha’s game plan for survival.

“The General Felt closing opened up a substantial number of opportunities for us,” Ling said, fingering one of the opaque stone chess pieces. “But you couldn’t get to that position until you cured the LTV problem. You couldn’t cure the LTV problem unless you could show them the values of General Felt. You couldn’t do that unless Marshall Cogan could get his financing. He couldn’t get his financing because of the obvious problems we had with Omega-Alpha and the possibility of Bankruptcy Act proceedings that would develop out of that sale.”

But General Felt’s sale had closed, and for the first time in months, Jim Ling obviously felt like the odds were running in his favor. “I feel strongly that we will be profitable and have a positive cash flow for the year,” he said. “I still have a number of things I’ve got to get done, though, to make it possible.” Before, when we had talked, Ling had estimated that he was at about move 5 or 6 (on a continuum of 12) toward solving Omega-Alpha’s problems. Where was he now? He answered instantly. “About 9 or 10.”

September would tell. For Ling, it was to be a watershed. The third quarter would end Sept. 30, and he would know exactly where he stood on cash flow. Obviously, he expected a bullish report. He expected to have another $2 million in cash on hand from the liquidation of some of the assets of the ill-fated TIC. By Sept. 17, he expected to have the votes from the debenture holders authorizing the one-year debt moratorium. If that occurred, he would have another $1.35 million to apply toward urgencies.

Moreover, for a change, Omega-Alpha had encountered a bit of luck. Its interest in a once-bankrupt Kansas equipment company had suddenly taken on value because of the energy crisis. Ling swiftly sold that interest for $400,000. His goal now was to continue selling off Omega-Alpha assets, including some securities acquired in the General Felt sale, and to refinance the company’s secured bank debt at First Pennsy at a more favorable rate.

Then came Sept. 17 and disaster.

Cashing in the Chips

Ling could not have been more stunned by the day’s events if some cowhand wearing pointed-toed boots had suddenly kicked him squarely in the groin.

First Pennsylvania Banking & Trust called its loan. Joseph Drennan, Ling’s principal banker, gave way. Uncled! Wolfed! Panic-buttoned! After all those words of praise that Drennan had heaped on Jim Ling, after all their hours and hours of conversation about how to salvage Omega-Alpha, after surviving first the winter and then the summer of Omega-Alpha’s serious malaise; now at the promise of autumn, of a turning point, Drennan had reached over and pushed the destruct button.

He gave Ling ten days to come up with $13.25 million.

Realistically, Ling could just have easily come up with hard evidence of the Virgin Birth.

The decision had obviously pained Drennan. “We worked with Jim, listened to his plays, to his hypotheses of how the company could work out of it. All indications were, from every plan that we looked at, that it was not viable. We had a good position, and we were not going to jeopardize that position.” But if the truth were known, Drennan admitted, the Eastern bankers had not been pleased with the outcome of the Lombardi Hotel negotiations, not nearly so pleased as Ling had intimated in his press releases. As of June 30th, the banks had been owed $15 million by Omega-Alpha. And even with the sale of General Felt 25 days later, Ling had paid them only $11.75 million. That left $3.25 million still in arrears, plus the $10 million balance remaining on the $25 million loaned by First Pennsy and two other Eastern banks.

Yet the key word in Drennan’s comments was the word “jeopardy.” The Eastern bankers were not going to let their secured position in Ling’s panoply of creditors be jeopardized, and in late August, that jeopardy had appeared.

Improbably, it had come from the folksy, avuncular Atlanta attorney, Robert Hicks, who was representing all of those Georgia folks who felt that Omega-Alpha had stolen their money while it owned the TIC home mortgage company. They had bought thrift notes in North American Acceptance Corp, a subsidiary of TIC. They had thought it was a safe form of savings; now they were wiped out. “These people were some of the most wretched, poverty-stricken people in Georgia,” attorney Hicks drawled. “You can imagine the pressures over here to investigate into the activities of Mr. Ling in looting the assets of North American to pay the debts of Omega-Alpha.”

Ling denies looting North American, but he couldn’t deny owing the bankrupt company $9 million. He couldn’t pay when Hicks called the note. And that, in turn, forced the Eastern banks to call their note.

The deadline set by the banks was a Friday late in September. On that particular evening, I’d forgotten Jim Ling’s problems until a sudden and unexpected confrontation with one of my choice downtown sources at a North Dallas business that night. “Listen,” I said in my best sotto voce voice, “I need another secret session with you.”

“It’s over,” he whispered.

“Over?”

“They filed today.”

The press release came the next day. “James J. Ling, Chairman of the Board and President of Omega-Alpha, Inc., announced today that Omega-Alpha had filed a petition in the Federal District Court in Dallas for relief under Chapter XI of the National Bankruptcy Act.”

Comparing the Post-Mortums

Could he have made it on his own? We’ll never know. The unaudited results for the quarter ended September 30,1974, showed a net profit of $222,000 as compared with consolidated loss for the same period last year of $1,689,000. Ling may have had reason for his earlier optimism.

We’re tempted to reach for a comparison between Ling’s debacle at LTV and the struggle for survival at Omega-Alpha. But, realistically, there’s not much of a basis for comparison.

Ling-Temco-Vought, Inc., was the country’s 14th largest industrial enterprise when Ling was ousted in the summer of 1970. On the other hand, among Texas companies alone, Omega-Alpha ranked only 80th in Texas Parade’s latest Top 100 listing.

For all of its problems in the 1969-70 era, LTV was an amalgamation of blue-chip steel making, meat packing, sporting goods, aerospace, electronics and airline companies. But Omega-Alpha never had more than one well-regarded subsidiary, Okonite, which Ling had acquired improbably from LTV after his departure.

At LTV, Ling lived like a sheikh-in-mufti, with expensive hotel suites, a $600,000 co-op apartment on New York’s Fifth Avenue, a flight of corporate jets, chauffeurs, a company ranch called the Eagle, and personal salary and benefits of $375,000 annually. But at Omega-Alpha, Ling agreed to jettison his few executive amenities (including a leased jet and a rented New York apartment) early in Omega-Alpha’s struggles and accepted a court-ordered cut of $35,000 from his contracted $95,000 annual salary.

While heavy debt problems led to his ouster at LTV and his voluntary bankruptcy at Omega-Alpha, the character of the debt differs. At LTV, Ling at least used his tremendous debt to buy companies that, if managed right, could turn a profit and later, if necessary, be sold. But at Omega-Alpha, Ling unwittingly used his borrowed money to buy a lemon, Transcontinental Investing Corp., which cost him great sums in both write-downs and operating loses while immuring him in law suits, diverting his energies and undercutting his investor appeal.

At LTV, Ling was hit by a numbing cannonade of problems: antitrust litigation, substantial operating losses, a sharp stock market decline that panicked shareholders, intra-board squabbling and personal financial difficulties -all atop the tremendous debt service problems. At Omega-Alpha, his primary predicament was relatively simple, if compelling. It was a matter of the deft juggling of his debt.

There is, however, one similarity between Ling’s two highly publicized brushes with fate. In both instances he used his creative financial talents to design a way out of the morass. At LTV, the grand design was under way when W. Paul Thayer took Ling’s place, and Thayer, while giving it his own style, kept faith with Ling’s general scheme. With Omega-Alpha, Ling also had a way out, and he thought it was working when panic hit the creditors.

Other similarities may exist, but they lie beyond the facts and figures. We’d have to probe the mind of James J. Ling and consider a personality that’s as complicated as the Omega-Alpha financial statement. Why, for example, this fetish for playing with extravagant amounts of debt? At LTV, it was empire-building, pure and simple, and it almost worked. But at Omega-Alpha, Ling seemed to operate under similar assumptions in a completely different circumstance.

In the heady days of LTV, Ling had seen the mountain. After that, is it so difficult to return to the fields, where common men labor by managing for profits? At LTV, Ling’s obsession seemed to be his ranking on the Fortune 500 list. At Omega-Alpha he sometimes seemed to be trying to whip together the magic formula that would – poof! – return him to his proper place. He is a headstrong, brilliant man with an enormous drive, and he has lost a lot of friends as a result.

If there’s little similarity between Ling’s position at LTV and Omega-Alpha, we can’t be sure he understood it anywhere but on the balance sheet. And the balance sheet, well, that could be corrected, if only…

If only. Those two words may be the final epitaph of Omega-Alpha.

One can’t help wondering if those who soar so close tothe sun aren’t blinded by the light. Then again, the pricemay be worth the flight.

Related Articles

Business

Wellness Brand Neora’s Victory May Not Be Good News for Other Multilevel Marketers. Here’s Why

The ruling was the first victory for the multilevel marketing industry against the FTC since the 1970s, but may spell trouble for other direct sales companies.

By Will Maddox

Business

Gensler’s Deeg Snyder Was a Mischievous Mascot for Mississippi State

The co-managing director’s personality and zest for fun were unleashed wearing the Bulldog costume.

By Ben Swanger

Local News

A Voter’s Guide to the 2024 Bond Package

From street repairs to new parks and libraries, housing, and public safety, here's what you need to know before voting in this year's $1.25 billion bond election.

By Bethany Erickson and Matt Goodman