Standing side-by-side, people are passing a lighted firecracker. Sparks are flying, the fuse is hissing, growing shorter, as they frantically toss it to the next pair of sweating hands. Now the fuse can barely be seen, and its holder’s eyes are bugging out. Oh sweet Jesus, please don’t let it be me.

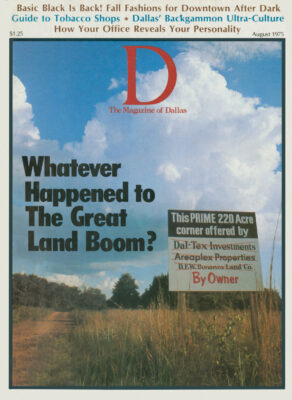

This isn’t a fraternity initiation ritual. It’s how people felt during the last days of the late, great Dallas land boom. At least, that’s how they talk about it these days at the Sailmaker, the hangout for the people who bought land and lost land – or let it slip away. Across the parking lot, at the 21 Turtle Club, you’ll find those who bought in early and rode it out. All these folks will tell you about Dallas’ business Bacchanalia, the days when everyone was drunk on land deals.

Those were the days, 1972 and 1973. Their passing is enough to make a grown man cry – and plenty of them did. “Back then you just couldn’t make a bad land deal,” recalls a former broker. “The best salesmen in this city were making $100,000 easy. If you were on the ball you could pull down $60,000, and anybody making less than $30,000 didn’t belong in the business. Selling land didn’t require much training. You just had to be socially acceptable to wealthy investors and turn some deals.”

The Great Dallas Land Boom didn’t end cleanly, like a book or play, but just sputtered to a halt sometime in late ’73, leaving thousands of speculators, brokers, small time investors and developers stretching to cover those payments they thought they’d never have to make.

The land story has its good guys and bad guys, winners and losers. Unfortunately it has none of those facile statistics which impress, and sometimes explain why things happen. Nobody really knows how many deals were closed, how much money was made, and how much was lost. No one knows how many doctors and pilots jumped into joint ventures and have yet to climb out, or how many savvy investors doubled their money. But we can report, with certainty, that it’s a buyer’s market for telephone-equipped Mark IV’s.

The cast of characters included men like Henry S. Miller, Chuck Wilson and Hank Dickerson – men who know how to survive. They roll with the punches, pull in their horns here, while expanding there. Then there are the Ken Goods, who rode the land boom to the top, did some backsliding, and are still hanging on today. And then the “syndicators,” a self-respecting land broker will tell you with a scowl, who have crawled back under their rocks, waiting for a fairer day.

Illogical, drunken, heady – choose whatever word you wish to describe the boom and you won’t be wrong. People jumped into deals without even looking. “What guy doesn’t want to make something for practically nothing?” says a broker.

But behind it all worked the force that propelled the boom or you might say, sucked it forward. The Bigger Fool Theory, they call it, which to the boom was as important as Newton’s three laws of motion are to the universe. “No matter how much you paid for a piece of land, it was a good deal as long as you could find a bigger fool to pay more,” recalls a broker who found his fair share of bigger fools. Land deals just kept being passed along like that firecracker, but one day it had to blow up. It did.

The land boom had its beginnings, predictably, in the Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport. “The world’s largest airport,” we were told again and again, in the bigger-than-life rhetoric that helped build Dallas on a scrubby prairie. “New cities, new industrial parks,” was the cry, furnishing fuel for the fabulous boom. But it was the floundering stock market that sprung the starting gate.

Since the close of World War II, the industrial average had risen steadily year in and year out for two decades.

The Dow-Jones Industrial Average broke 200 in 1949, sailed past 500 in 1956 and by 1961 topped 700. Through the ’60’s it climbed higher and higher – 800, 900 – and brushed against the magic 1,000. But then came the turbulence of riots, Viet Nam and inflation. The market began to pitch and yaw; now the ups were interrupted by downs. The margin requirement tightened. In 1970 you could borrow 80 per cent of the market value of your stock, but 18 months later you could borrow only 55 per cent. Investors started looking around for an easier way to make money.

Along came undeveloped real estate and the joint venture. “Back in 1970 when 35 other guys and I were working around town trying to sell land,” says broker Dan Tomlin, “very few investors knew anything about real estate and practically none had heard of a joint venture.”

Joint ventures were brought to you by the people who designed mutual funds and real estate investment trusts, so small investors could team up and make big deals. Typical of a joint venture is one which recently sold half of its 32-acre property in Piano, for an $85,000 profit. A Dallas broker selected the land and rounded up 15 investors who pitched in down payments ranging from $2,750 to $16,500 each. The land was purchased in August, 1974, at $19,000 an acre. Joint venture participants, held together by an agreement, do nothing but make payments while waiting for their broker to sell the land; he picks up a six per cent commission for the sale, and often part of the profits.

Brokers started turning deals right and left around the edge of D-FW Airport during the late ’60’s, feeding off of investors anxious to achieve a sizeable return in the great land rush. Possibly abetting the rush was a unique situation created by tax laws. The cities of Dallas and Fort Worth condemned 17,500 acres of farm land for the airport, and paid cash for all of it. Profits made from condemnation are different from any other land sale profits – if they are reinvested promptly in more land, the owner can postpone a capital gains tax and continue to postpone the tax as long as he keeps reinvesting his profits in land. So the farmers and the speculators had every reason to reinvest in land, and why not reinvest around the airport? Some brokers think they did.

Others doubt that the farmers themselves jumped into land speculation. “Farmers are farmers, and I imagine they just went off and bought themselves more farms, paying cash,” says a broker. “Land syndication is for the Master Charge generation, and the farmers were interested in turning furrows, not land deals.”

First among the big-time brokers to leap into the airport was Ken Good, who had left Henry S. Miller to form Good & Associates. Good’s brokers began buying up acreage in the late ’60’s for James Redman, chairman of Redman Industries, eventually tying up 400 or 500 acres northeast of the airport. Next Good organized a mammoth joint venture, closing in December, 1969, an 842-acre tract located north, east and west of Sandy Lake Road and Denton Tap Road. In exchange for the financing, SMU was given 20 per cent of the land, valued at $500,000. Today Good is out of the deal; his investors remain optimistic about their chances to make a profit. “After putting that joint venture together,” says a former Good associate, “I think Ken decided he’d extended himself far enough, so he backed out of the airport market – at least for a while.”

Next in was Henry S. Miller, whose brokers began buying up land right and left during 1970 and early ’71, replacing Good as the major force in the area. By 1973 Miller’s holdings for joint ventures and individual investors in the area approached 1,000 acres, principally near the northeast edge of D-FW. Although other investors swarmed in, none achieved the dominance in airport area speculation attained by Good and Miller.

Land deals started flowing north from the airport at an incredible pace, gobbling up land that won’t be developed for decades. People were paying prices as if development would happen next week. The truth, as many now know, is that development creeps forward at a snail’s pace, and some folks are now holding land with stiff payments – land which won’t be developed in their lifetimes.

Why? “When land hit $10,000 an acre on the airport’s edge,” says the president of one of Dallas’ most respected brokerage firms, “people realized that $10,000 an acre was all some of that land would ever be worth. Some stayed and paid more, but others moved out a mile or two and bought land for three or four thousand an acre, figuring that the airport really wasn’t that far away, and the land sure was a lot cheaper. With the airport so close, it was just a matter of time until their land would be worth $10,000 an acre.”

But the sobering fact is expressed by another broker: “On an aerial photo, land a mile or two away from development is only this far away,” he explains, holding his thumb and forelinger two inches apart. “But study development patterns and then go drive that mile or two, and you’ll find that land you bought is 10 or 20 years from development.”

But logic had nothing to do with it. It was superseded by the Bigger Fool principle. Starry-eyed land buyers moved north from the airport. Somebody came along and paid $5,000 an acre for a tract that was bought a few months earlier for $4,000, and it wasn’t long until a Bigger Fool saw land prices going up, so he paid $6,000 for the same land. The original buyer who paid $4,000 moved out a bit further and bought in for two or three thousand, starting the whole cycle again. The process continued, racing north, leaving D-FW and reason far behind.

Prices around the airport climbed higher and higher, putting most tracts out of reach for all but the biggest investors. There are many stories about Texas size land deals at D-FW, but none as good as those about the deals offered the Byer family, which owned approximately 2,500 acres east of the airport. The land was controlled by Ed Byer, co-founder of Garland’s Byer-Rolnick Hats. In 1971 Byer was approached by Ken Good’s broker carrying an offer from a subsidiary of University Computing Corporation. He was offered $1 million in escrow immediately and $29 million cash to be delivered one year later, upon closing. Byer refused, saying he wanted the deal closed in 60 days, with his $30 million in the bank.

The next offer was presented by Univest brokers, on behalf of a major corporation. The corporation offered $7 million in cash and $23 million in its common stock, listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Byer turned that one down in mid-1972, stating that he wanted all cash.

Univest brokers returned again, eyeing a million dollar commission on a deal that seemed impossible to refuse. Byer had died in March, 1973, so negotiations were carried on with the family lawyer. This time an Irving man offered $30 million in cold cash. The three-page contract called for $1 million in escrow and the remaining $29 million in 120 days. The contract’s deadline, March 29, 1973, passed without the family’s approval, and to this day no one outside the family knows why the offer was refused.

While the mania continued around D-FW, a case of land fever, the likes of which Dallas had never seen before and hasn’t seen since, appeared in Collin County, just to the north of Dallas. A $120 map sparked untold millions in land sales.

A gentleman named Jim Mitchell, undoubtedly unfamiliar to anyone outside the land business, unlatched Pandora’s Box and loosed a swarm of brokers on Collin County. Mitchell Map Company makes maps for oilmen – maps which detail not only topography but also ownership. Any county with oil or valuable minerals would have been detailed on an ownership map years ago, but Collin County, devoid of oil and minerals, hadn’t been mapped. Without an ownership map, the only way to find out who owned what piece of land was to travel up to the Collin County Courthouse in McKinney, a 35-mile drive up Highway 75.

And when you got there: “That place is awful,” says a broker. “It smells terrible and the ownership records are archaic. You might spend three hours trying to look up a single owner and never find him.”

During the summer months, which are slow for businesses related to oil exploration, Mitchell decided to send unoccupied employees to the Dallas County Courthouse to look up ownership tracts and draw an ownership map. Real estate brokers bought his Dallas County map enthusiastically, so Mitchell decided to map Collin County.

“Brokers were always coming in and asking when we’d have Collin County finished and I’d just tell them we’d finish the job whenever we could get around to it,” Mitchell says. Brokers were hungering for Mitchell’s map, and when it finally came out, they snatched it up and descended on Collin County like locusts.

“We just sold the hell out of those little maps at $10 apiece, for a one-twelfth section of Collin County, or $120 for the whole county,” Mitchell recalls. “All told, we spent about $10,000 producing that map and sold about $40,000 worth. It was just a little sidelight for us, and when the real estate slump hit, we quit making them.”

George Roddy’s experience was as remarkable as Mitchell’s. Roddy was a Dallas County map and plat department employee who spent his days updating courthouse land records. Broker after broker complained to Roddy that there was just no easy way to keep track of land sales, so Roddy began moonlighting, keeping simple records of major Dallas land transactions, which he sold to brokers. Before long Roddy hired someone full time to help him, and in 1970 he resigned his county job and started the Roddy Report.

The Roddy Report listed locations, size and purchase price of land transactions, and was sold to brokers monthly for $8.50. Brokers could see where sales were occurring, and more important, could locate “compara-bles,” pieces of property which resemble land that they might be trying to sell, and can thus be offered at a comparable price. With the Roddy Report, finding comparables was a cinch. In 1971 Roddy added reports on Collin, Tarrant and Denton Counties, and by 1973 was selling 275 a month. No small wonder, since during the Collin County land boom that area alone produced 150 major land sales a year. By 1974, that number had dropped to about 20. Today Roddy’s business is thriving, and his company, DRESCO (Dallas Real Estate Services Company), produces reports in 23 Texas counties and ten in Colorado.

Next was Rockwall County, northeast of Dallas and 40 miles from the airport. All it takes to start a land rush is one big developer setting foot in an area, and in 1970 Centex, one of the nation’s largest single family housing developers, set its big foot down in Fate, Texas. Centex bought 2,000 acres at Fate, which is five miles east of the City of Rockwall. Soon as word got out that Centex was in, speculators scrambled up to Fate like suckling puppies, because among all the madness, there is one immutable land development law: single family home developers lead the way. Without them there are no shopping centers, no office buildings, no people. A home developer could buy 1,000 acres on the moon and speculators would land on the next rocket. Now you might wonder just why a developer leaps over miles of vacant land to buy out in the boonies. The sane thing to do, it would seem, would be to build houses next to other houses in places like Richardson or Carrollton. But speculators had driven prices so high in north Dallas County that developers fled to places like Lake Dallas and Fate to find land cheap enough for middle class housing. But even there an average single family lot today costs $6,500, up from $4,400 four years ago.

Big time developers are capable of starting their own land booms, and often do, in places like Fate. Fox & Jacobs did it in Piano in 1971 when it bought 500 acres west of Central Expressway and Parker Road, starting the land rush west of Central Expressway. Two years later Fox & Jacobs bought 2,600 acres east of Lake Dallas for The Colony, igniting the land boom there.

Some of those speculators are learning today that companies like Centex can sit on land for years without making a move. But many speculators can’t sit around meeting land and tax payments while Centex farms, which is exactly what’s happening at Fate right now.

A few speculators have also learned by now that not all big name land buyers intend to develop those 500 acres they buy. But whatever their motives, they create a market by moving in. Such is the case up at Frisco, a sleepy Collin County community. Enter the Carlton Company, owned by developer Irv Deal, whose other entity, Deal Development, builds apartments and condominiums in ten states. Carlton moved into Frisco in 1972, buying large tracts of land not for development, but for resale. Carlton’s business is land investment, and the only thing it develops is a land market. Other salesmen started running around whispering “Irv Deal’s buying in at Frisco,” and a pack of speculators scurried along behind Deal. “Because we’ve been in the business I suppose people might respect our judgment,” says Deal. And indeed they do. Since 1972 Carlton has sold some of its Frisco land, but the market is still there, apparently because a pro once touched it, and in fact, several brokers are convinced Frisco land is the best buy available today.

“It’s amazing,” says a broker. “All it takes is for Irv Deal or Bobby Fol-som – anybody with a reputation – to move in, and it starts. Never mind that they might not intend to develop the land. People figure if one of these guys bought the land it must be worth plenty because they are pros.” Then why would anybody want to buy the pro’s land if the pro is moving out? “Hell if I know,” he says. “Just because Irv Deal’s been there the land’s worth a bundle. I can’t explain it.”

Sometime in late ’73 the land boom flat burned itself out and was replaced by the eerie silence of inactivity. Land markets, unlike stock markets or commodity markets, don’t have daily listings or indexes. You can’t point to the line on the graph where the land market dived to the floor.

If the New York Stock Exchange has its headquarters on a Wall Street trading floor, the Dallas land market headquarters was in the Sailmaker, a bustling bar at Oak Lawn and Blackburn. During a typical happy hour you’d find hundreds of brokers, bankers and real estate secretaries in there talking at the stand-up bar as if it were a specialist’s trading counter. “I wish I had one per cent of all the deals closed in there,” says former owner Larry Morrow, who watched the boom build and bust.

“I remember when conversations changed from deal making to crying on each others’ shoulders about what happened to all the action,” Morrow recalls. “If anything, our business picked up. They had plenty of time on their hands and I guess they were just crying in their beer.”

There’s no doubt what killed the land boom – money simply evaporated. Moving real estate is like moving an assembly line. A broker buys from the farmer, and the land travels down the assembly line, changing hands from one buyer to another, moving toward the developer. The developer pays cash for the land, builds on it and the real estate cycle is finished. But when money dried up, the developer couldn’t buy land, much less finance construction, so the assembly line stopped.

There is no poison more virulent to a developer than a rising prime rate – the interest charged a bank’s biggest borrowers. Developers need huge amounts of cash to finance shopping centers, office buildings or homes, and they get mortgage money from life insurance companies and savings and loans, whose rates tend to follow the banks’ prime rate. When money is scarce, interest rates go up, and at a certain plateau, the developer just stops building, and won’t start again until rates come down to a reasonable level.

Says Mack Pogue, chairman of Lincoln Property Company, the nation’s largest apartment developer, “We built 9,000 units in 1973, 5,500 in 1974 and then the long term interest rates shot up. Right now we have plans and the land for 3,000 more units, and we’re ready to go, but we won’t start until we can get nine per cent, and we’re waiting it out.” During the recession not only were interest rates high, but the scarcity of money kept developers from borrowing even at high rates. And when developers don’t develop, they go broke, as many have during the last two years.

The most critical relationship affecting the real estate market is that between the prime rate and single family housing starts. The higher the prime rate, the lower the number of single family housing starts. You can count on it.

The prime rate dropped to five per cent in 1972 and remained low through 1973. Housing starts, nationally, were at an all-time high. Then the prime rate skyrocketed, reaching 12 per cent in 1974, and housing starts plummeted. (Last year short term construction loans hit 16 per cent.) In Dallas starts fell from a high of 14,574 in 1972 to 8,979 in 1974. The same slump continued during the first four months of 1975, with starts off 40 per cent from the same months of 1972. Big developers hibernated; small developers went broke; the land boom fizzled.

No doubt the real estate business was doomed anyway, but the Dallas fall was long and hard. The market had worked itself into a frenzy, and the piper had to be paid. “The fundamental error in Dallas was simple,” says Dean Manson, executive director of SMU’s Costa Institute of Mortgage Banking. “Real estate ceased to be governed by the principles of real estate. It was treated as a commodity, like a sack of potatoes or a bushel of corn. Real estate has certain values and a piece of undeveloped land is not worth more than a developer is willing to pay for it. A commodity is worth what anybody is willing to pay for it.”

Says Ben Pinnell, who bought in early at the airport, “A piece of land clearly has a value, and that value comes from things like zoning, housing demand, availability of utilities, the value of the dollar and the terrain. These things dictate what a developer is willing to pay for it. When you forget about all of that and set its value at what a bigger fool is willing to pay for it, then things get bent out of shape.” Adds Manson, “I was trying to study real estate principles in the Dallas land boom, and soon enough I discovered none were being used.”

A land buyer needs to estimate what a developer will be willing to pay for a piece of land in a few years, when the developer gets ready to build. Generally the developer will be able to pay what he’s paying today, plus whatever dollars inflation adds to that price between today and the time development starts. If the buyer pays $10,000 an acre for land that in five years a developer can only pay $8,000 an acre for, the land is overpriced. Either the buyer must sit on the land until inflation drives the price up to $10,000, or he must get out. Getting out rarely means a sale – usually it’s a foreclosure. If skyrocketing prices marked the rising tide of the boom, then today’s many foreclosures evidence its ebb.

“Punting” is the market’s way of getting prices back down where they belong, and when a buyer decides he doesn’t want his land, he simply walks away from the deal, forfeiting his payments, and hands the land back to its previous owner. This “no personal liability” feature of land financing is what makes land deals easy to get into and easy to get out of. If the buyer doesn’t want to keep the land, he merely returns the land to the seller and the note is canceled. The buyer is not obligated to pay off his note in cash. In effect, the “no personal liability” feature makes the sale an option – the buyer’s payments give him an “option” to continue paying off his note and keep the land, or he can opt to quit making payments and return the land to the seller.

Even the best brokers punt once in a while. Such is the case with Henry S. Miller, who once paid $23,850 an acre for some airport land which has since been punted back to $5,000 an acre. In August, 1969, land investor Carroll Williams bought 80 acres southeast of Denton Tap and Sandy Lake Road northeast of D-FW, paying $5,000 an acre. Williams held the land for several years before selling to another investor, Roland Arthur, at $17,500 an acre. In late August, 1973, Miller, acting as a trustee, bought the property for $23,850 an acre, then tried to sell the property at $30,000 an acre, but along came the crash.

Last spring Miller decided to punt the deal, so he didn’t make his interest payment on the $23,850 an acre note. Miller punted the land back to Arthur, who now had no income to pay his $17,500 an acre note, so he punted the land back to Williams. So now, five years after Williams sold the land, he had it back, along with five years of interest payments. The land had gone from $5,000 an acre to $17,500, up to Miller’s $23,850 an acre and wouldn’t sell at $30,000. The land quickly skidded back down to $5,000 an acre, where it stayed until recently when Williams sold it for $10,000 an acre.

Chains like this one can, and do, build with five or six buyers purchasing the land, each making nothing but tax-deductible interest payments. But if the land is overpriced and another speculator or a developer isn’t willing to buy it, the last buyer gets burned, and everyone along the chain of transactions gets singed.

No one really knows precisely who lost the money and who made it. Land deals are still being punted. Those who have staying power – the ability to keep making those annual payments until the building drouth ends, can still make money, if their land isn’t overpriced. Make no mistake, people are making money today in a land market which seems unrelated to the flimflam market of yesterday, spurred on by unscrupulous salesmen preying on unsophisticated investors. Burned the worst are those that could afford it the least – investors who couldn’t afford to stay in the land market, but were promised that after one or two payments their land would sell. Many of those broken promises were made by salesmen who have long since drifted off to sell other things, but the shadow they cast remains over even the most legitimate brokers who are in the business today.

One salesman, who now does clerical work, recalls with regret his days in syndication: “I got into it because I was collecting finders’ fees from salesmen who were selling to my friends. Then I realized I could have the whole commission myself, so I started selling. I wish I’d never done it. Hell, it’s tough to get up in the morning, look in the mirror and say ’hi’ to a fool. You think that’s bad, try looking at your sweet aunt and uncle who bought some of the crap you were selling.”

One of the most meaningful statistics is how many deals a syndicator sold to its investors, and how many of them have since resold. Naturally most companies guard this statistic with their lives, but one which apparently doesn’t is Metroplex Properties. Metroplex Properties is essentially the same company as Love-Henry & Associates, which in 1973 was ordered by the State Securities Board to stop selling unregistered securities. LoveTienry sold 109 land deals to its in-vestors, and today “82 or 83 of them remain in the same investors’ hands,” says employee Patti Hoff. “But we have not had one fall – the payments have all been met, and in this market, I feel real fortunate,” she adds.

Since the State Securities Board stopped Love-Henry’s syndications, John Love and his new company, Metroplex Properties, are selling “straight” real estate. Typical of such a straight real estate deal is Love’s Metro Park South, a proposed industrial park in Italy, Texas. Mention of Metro Park South will bring hoots from practically any Dallas broker, but Metroplex Properties stoutly defends it. Metro Park South is a 330-acre tract located just off Interstate 35, 47 miles south of downtown Dallas. By now “phase one” of development should have occurred, but the tract remains farmland. Love carved up the tract into one acre parcels, which he sold to individual investors, giving them the title. This “straight” real estate deal avoids undivided joint ownership and thus supposedly avoids regulation by the SEC or State Securities Board. The land was purchased by Metroplex for approximately $1,100 an acre, and was sold to investors for approximately $6,500 an acre. The enormous profit taken in by Metroplex is supposed to pay for the development of the land, which hasn’t started yet. State officials are eyeing the project carefully at the moment, looking for possible violations of securities laws.

Metroplex is gambling on a concept it calls “rural industrialization,” and while some think its chances of developing a major industrial park in Italy, population 1,300, are ridiculously low, Metroplex maintains that companies will want to move to Italy and that workers will be willing to drive from as far away as Dallas to find employment in Metro Park South.

John Love had a unique idea for financing Metro Park’s land taxes. He suggested including with each parcel of land a cow, which, with the aid of a bull supplied by Metroplex, would produce an annual crop of calves. Proceeds from calf sales would pay the taxes. Novel as it was, Love’s idea never came to fruition.

Probably the worst after-effect of the land frenzy is the fate of thousands of naive investors who were snookered into joint ventures and limited partnerships by an array of artifices that would make Harry Houdini’s illusions look amateurish. Hidden commissions, markups, hokey investment seminars and non-existent escrow accounts were all a part of the monumental ripoff.

One syndicator selling in Dallas, Regional Airport Investments Inc., was accused of buying land under one corporate name and then turning around and selling it to Regional Airport’s investors with a 90 per cent markup. Regional Airport’s owners didn’t bother to show up and deny the charges at a State Securities Commission hearing which resulted in a cease and desist order.

Perhaps the most dramatic case, which is generating accusations of fraud, can be found by examining the remains of Bachinskas-Nation, a wheeler-dealer syndicator that fell apart last year. To this day court-appointed receivers are still trying to figure out how many people invested with Bachinskas-Nation and where the hundreds of thousands of dollars they invested went.

Bachinskas-Nation was organized by Eddie Bachinskas, who served as chief executive officer, and his father Ed Bachinskas Sr., an LTV mid-level manager whose name and LTV position were touted on Bachinskas-Nation literature. Like most syndication operations, Bachinskas was staffed by super salesmen who knew little about real estate, but plenty about selling. Salesmen were psyched up at weekly staff meetings, where Bachinskas officers delivered emotional pitches on each of the joint ventures, convincing sales personnel to go out and sell the deals.

Federal and state legislation requires that public offerings of land syndications be made only to “sophisticated” investors. Syndicators like Bachinskas-Nation sold land ventures to many people who knew nothing about land, but relied on inflated promises from salesmen, who were paid an immediate commission for bringing in an investor, and had no reason to care whether the land was ever resold.

“Those guys went out and sold crap to doctors, pilots, meter readers and pole climbers,” says a Dallas broker. One such victim is an American Airlines pilot, who put nearly $2,000 into a Bachinskas land deal that was never closed. “I just lost my poker money,” he says. “I don’t gamble with my eating money and I don’t mind losing a little poker money in a straight deal. But I don’t like being rinky-dinked. I just needed a tax break, so I jumped in without looking. I should have known better when I saw how much money they were taking off the front end.”

Enormous cash rake-offs from the front end of land deals keep companies like Bachinskas moving. Typical of such a deal was one of several Mansfield, Texas, joint ventures, which finally brought Bachinskas-Nation tumbling down last year. Total price of one venture was $146,000, with more than $39,000 – 27 per cent – to be put down in cash. Bachinskas was planning to pocket $24,000 of the down payment, so most of the down payment was scheduled to go into the company. In a reasonable land deal, investors wouldn’t be charged much front end money.

Court-appointed receivers found Bachinskas-Nation cashed $460,000 in investors’ checks written to escrow accounts which didn’t exist. The Mansfield tracts were not purchased with the escrow money; neither were substitute tracts at Pilot Point in Denton County. The $460,000 evaporated.

Attorneys Khent Rowton and David Kelton have spent more than a thousand hours trying to account for an estimated $3 million Bachinskas apparently raised in less than a year. So far only half has been accounted for, and efforts are being hampered by what’s left of the company’s financial records, two small ledgers and check book stubs, which contain vague entries such as “Checks 401-410, miscellaneous commissions.”

Among the “sophisticated” investors located so far, is a Mexican-American couple who invested $4,000 from $7,000 they received in condemnation of their home. They don’t speak English.

Bachinskas’ financial operation was no less peculiar than the rest of the company’s operation. Eddie Bachinskas’ executive bathroom included a picture poster of Marlon Brando as the Godfather, saying, “Make them an offer they can’t refuse.” A former Bachinskas officer tells about the time when an officer was fired, but not before his desk had been cut open to retrieve incriminating records. Toward the end Bachinskas hired three armed guards to stand outside his office to protect him from one of his top officers who threatened to “beat the hell out of Bachinskas.”

Bachinskas sales technique can best be illustrated by quoting straight out of its sales training manual, which includes such headings as “A Golden Opportunity – Chance of a Lifetime – The 1973 Gold Rush,” and declares, “The end is nowhere in sight.”

The manual suggests this opening sales pitch: “If I could show you a way which would produce a profit of 100 – 200% on an investment in 1-3 years would that be of interest to you?”

The manual also includes a section on “Stalls and Objections,” a programmed response to a potential investor who isn’t ready to plunk his money down on the spot. Some samples:

Customer: I don’t have the money.

Salesman: Have you made a net worth statement lately?

(Find his money for him.) Customer: I’ve got money coming in about six months. Come see me then.

Salesman: Why wait? Certainly you can borrow and pay the interest while investing.

Customer: Let me think it over.

Salesman: Why? … If I allow you to just think it over, I will be doing you a disservice. Real estate values are escalating, population is increasing… Don’t let the future pass you by.

Customer: I knew a guy whose lot didn’t sell.

Salesman:… Bachinskas-Nation does not just sell you a lot and leave you.

Before it ended, Bachinskas-Nation was staffed by a dozen former LTV executives who had left $25,000-a-year jobs to make their fortune with Bachinskas. Today most of them have found their way back into other jobs, still coping with the nightmare. One former officer speaks painfully of the year he spent with Bachinskas. “I really prided myself on my reputation for honesty and my judgment of people. After I realized what I’d gotten myself into, the blow to my ego was indescribable. I’ve spent months brooding over what that year has done to me, and if it weren’t for my family, I don’t know if I could have made it through, thinking about what I’d done.” Another former LTV employee is paying legal fees to the receivers, not only for his share of 15 joint venture investments, but for those of his friends and relatives who invested on his advice. He is paying what he can, “out of a moral commitment.”

No doubt one day, and maybe soon, developers will start churning out the projects, exhaust their current land inventories, and search for more. Once again the delicate real estate machinery will be cranked up and people will be watching to see whether the machinery will overheat or run amuck.

No doubt thousands have learned that leverage can undo those who created it. Leverage, taken to extremes, becomes financial anarchy. In 1971, 10 or 15 per cent down would get you a piece of land, but by 1974, no down payment and just a year’s prepaid interest would suffice for a sale. “I should have seen it coming,” said a former broker. “When prices climbed so high an owner couldn’t ask for more than he paid, he just made the terms easier so he could make a sale.” Leverage became scarcely more than an option to buy the land, merely an attempt to postpone the inevitable crash.

The heads of the real estate departments of First National Bank and Republic National Bank claim their banks had little to do with the credit stretch. “The real estate fall came from loose credit. We wouldn’t make a loan to someone whose only hope of repaying the loan was if the land sold to another speculator,” says Denny Wallace of First National. “We would make a loan if development was imminent.” But even the banks were stuck on a few loans when development funds dried up almost overnight, a situation no one expected. Says John Stuart of Republic, “We were concerned from the beginning about people who were buying a dream, not real estate.” Though the banks deny that they played along with the credit stretch game, one of the city’s top brokers dryly says, “Baloney. They were in it, too.”

For the thousands who played the game unintelligently and lost, there are lessons to be learned. The American Airlines pilot who sank money into Bachinskas deals that never closed speaks philosophically today. “Well, you know there’s a sucker born every minute, and I guess I was one – this time.” Even the brokers who thought they couldn’t go wrong and reinvested their commissions in their own deals bear up well. “Now that it’s over, most of us have nicer cars and nicer homes than we had before, even if the deals turned bad,” one says. “But I imagine some of those guys who bought Highland Park homes are mowing their own grass these days.”

“I’d get back in the business in a minute,” adds a broker who’s now out of it. “Selling land in a good market can bring you instant success and all the accouterments that go with it, and that’s nice.” It’s the same reason that a guy puts another ante on the table, even after a losing hand. The game is exciting, and fate can always deal a better hand.

There are certain constants that won’t change, phenomena like the Greed Factor and land’s magnetic appeal to the investor. “Let’s face it,” explains a broker, “owning land is a big ego trip. A guy can drive out to the country and point to a patch of trees and say ’that’s my land,’ though he may own only 2 1/2 per cent of it.”

One deterrent that might prevent unconscionable syndicators from preying on unsophisticated investors, should the boom return, is sadly absent. Despite the plethora of ripoffs during the Great Dallas Land Boom, not one syndicator has been indicted, although signs point to criminal indictments this summer in at least one case. Nearly all of the syndicators slapped with legal action like cease and desist orders are selling real estate today. The SEC and the State Securities Board have no power to bring criminal indictments, a duty belonging to the U.S. attorney’s office, which is doing nothing, and the state district attorneys, who after considerable prodding, have finally begun to take an interest.

Never let it be said that people didn’t make money in land – they did, the people who knew the risks, knew that land wasn’t worth anything unless a developer bought it one day. They were the people who had money to invest, money that could ride out the real estate slump, patient money.

“People who can’t get in and stay in ought to stay out of real estate,” says broker Dan Tomlin. “If you can afford it, land is a great investment, providing you have a broker who knows the market, knows development and does his homework.”

Dallas broker Chuck Wilson adds, “Look for the firm to take a piece of the deal itself. When a salesman comes to me and says he’s got a hot deal, my first question is ’How much of the deal are you going to take?’”

Patience is a virtue in making money on land, and a glance at one of Trammell Crow’s deals illustrates the point dramatically. Back in 1958 Crow bought frontage along what is now LBJ Freeway at Valley View Center. Crow paid less than $5,000 an acre for land which now is part of Valley View Center. Five years later, in 1963, he sold some of the same land to Homart Development Company for $20,000 an acre – a 300 per cent profit in five years. Homart built Valley View Center and land values in the area have skyrocketed.

Even in a tumbling market there’s money to be made in land, and people who have some cash are doing it today. There are plenty of shrewd investors stepping in to assume defaulting notes on land which in a few years will bring a handsome price.

Painful though it was, collapse of the irrational land market brought about a much needed purge. “Hopefully we’re rid of a market based on wild speculation, and have rooted out most of the syndicators who fueled it,” says Dan Tomlin. “Now we can get back to basics, which means buying land and holding it until developers come along and buy it from us. Now that’s rational.”

Talk to dozens of brokers and they’ll split down the middle – some, like Tomlin, think the purge is over, while others are waiting for another frantic, insane real estate market. That’s the key question. Can it ever happen again? Will it ever happen again?

Who knows? Maybe Mack Pogue of Lincoln Property, who has spent years watching the land market all over the United States. “I’ve never seen anything like it before in Texas,” says Pogue. “The speculation market was entirely artificial in Dallas and Houston, but I don’t think it’ll ever happen again. The land market went wild ten years ago in California but wild speculation has never returned. People out there are still petrified.”

Related Articles

Arts & Entertainment

VideoFest Lives Again Alongside Denton’s Thin Line Fest

Bart Weiss, VideoFest’s founder, has partnered with Thin Line Fest to host two screenings that keep the independent spirit of VideoFest alive.

By Austin Zook

Local News

Poll: Dallas Is Asking Voters for $1.25 Billion. How Do You Feel About It?

The city is asking voters to approve 10 bond propositions that will address a slate of 800 projects. We want to know what you think.

Basketball

Dallas Landing the Wings Is the Coup Eric Johnson’s Committee Needed

There was only one pro team that could realistically be lured to town. And after two years of (very) middling results, the Ad Hoc Committee on Professional Sports Recruitment and Retention delivered.