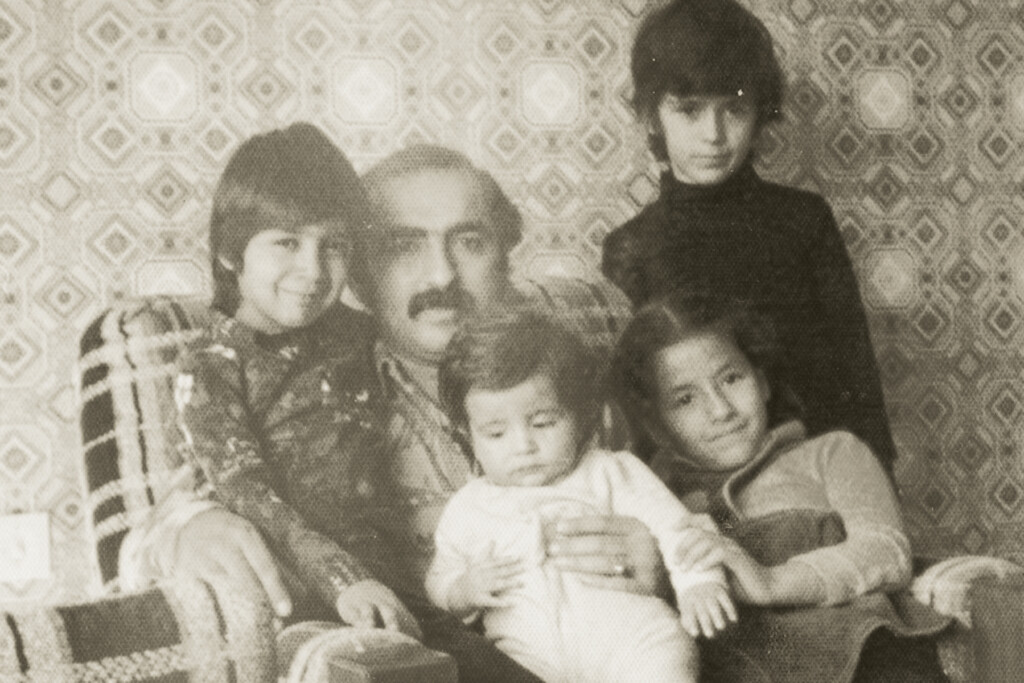

Entrepreneur Farzad Vahid fled Iran with his family during the country’s revolution in the 1980s, finding shelter in Spain before landing in Southern California. Vahid started his first company, Fornida, in 2012. Four years later, he moved to Dallas to launch a second enterprise hardware startup, ZaynTek. He added Habitat Commons, a Plano-based coworking space for creatives, last year. Here, he shares how being an immigrant has shaped him as a leader:

“We left Iran when I was about five or six. I do remember riding my bike there, and I remember my nanny. She started living with us when I was 10 days old. We had a bunch of family in Iran, but a lot of them started moving to the U.S, especially after the revolution. When the revolution happened, everybody tried to leave, but some people couldn’t. My parents were in the embassy getting my paperwork. Both their green cards had expired, and back then, I was not a U.S. citizen. I had never had a U.S. passport or anything, but my sister was a U.S. citizen. She was born in Newport Beach.

“In Iran, they were bombing their own people. I remember my parents would turn all the lights off, and when you were really quiet, you’d hear planes flying overhead. That was really nervewracking, but my parents would try to make it into a [hiding] game for us. After the revolution happened, Iran just wasn’t a good place to be.

“On November 4, the U.S. Embassy got attacked in 1979. I remember my mom told me she got hit in the leg with a can of tear gas. My parents helped the the six U.S. citizens who lived or were working inside the embassy escape out the back, and they got a letter from the Reagan administration thanking them for helping. After the attack, my parents were supposed to go back on November 7 to get my paperwork. That never happened. They couldn’t get my paperwork. My dad went to Switzerland to try and get my paperwork to get me to go to the U.S.—a green card or some some kind of entry into the U.S.— and they wouldn’t allow it. [The people in the embassy] told my dad ‘You have to wait until your daughter is 18, and then she can apply for you.’ This was in 1979 and 1980. In 1982, they decided, after talking about it with some of our family who were already in the U.S., that we were just going to escape—flee through Pakistan and somehow get to the U.S.

“When we were going to leave, my parents told my nanny that we were going to leave, and she said ‘If you’re going to leave, I’m just going to kill myself or you’re going to have to kill me. I want to come with you.’ She thought of me as her son. So, my parents paid for her to come as well, and she lived with us until 2010 when she passed away.

“We had to pay $10,000 a head to have somebody smuggle us out. My parents left everything behind. I later found out that my mom was pregnant at the time. She had to get an abortion, because if we got caught, we were going to go to prison. She didn’t want to have the baby in prison. My mom and dad sacrificed everything for my sister and I to get out of there. We were smuggled in a truck across the border. When we got to Pakistan, we got to an airport, then my parents and I flew to Spain. My sister flew directly to the U.S., and she was with family in Laguna Hills, California. My parents stayed with me in Barcelona for a while. They flew to the U.S., and they got to immigration, and they had expired passports. My dad told the customs agent the entire story of them escaping. She stamped their passports and said, ‘Welcome to the United States.’

“When we came to the U.S., our family had one house in Laguna Hills. It is a three-bedroom condo that my uncle bought a long time ago. Probably 40 or 50 families have come and lived in that condo at some point then got on their feet, moved out, and bought their own homes and started businesses. I lived there with my grandmother, my aunt, my dad, my mom, and my sister. We moved out after a year of being there.

“I was put in first grade, and I didn’t know any English. I remember being in school, and my uncle would come and ask the other kids ‘Why aren’t you guys playing with Farzad?’ The kids would say ‘We can’t. He doesn’t know how to speak English.’ So, my uncle said ‘Well, teach him how to speak English.’ I remember them teaching me to say ‘choo choo’ for train. I started learning how to speak English from my friends, not from school. From what I can remember, school didn’t help. I remember my first grade teacher, Mrs. Cook. She was super nice, but I was just confused always in class. I learned how to speak English on the playground essentially.

“Being an immigrant gives you that mentality where you’re never going to give up. I look at what my parents did and what they sacrificed. They came here with nothing, so if I lose it all I can build it again. I think that’s the biggest mindset difference between immigrants and people who were born here.”

Get the D CEO Newsletter

Author