Former Dallas Mavericks standout guard Rolando Blackman—whose No. 22 jersey hangs in the rafters at American Airlines Center—was raised in Panama until the age of 8. In 1967, he moved to Brooklyn to live with his grandmother, before college at Kansas State University and a 13-year NBA career. He’s now vice president of corporate relations and a diversity, equity, and inclusion ambassador for the Mavs. Here, he shares how he tapped into the passion and intensity that has fueled his success:

“When I was growing up, my mom and dad fought like cats and dogs,” Blackman says. “I remember them yelling and cussing all the time, from the time I was 5 years old until I left Panama at 8. There were physical fights on a regular basis. My sister and I tried to break up fights, and I remember leaving those altercations with busted lips. My extended family gave me all the love and care, but inside of my own house, things were tumultuous.

“As a result, even today, I sometimes have to temper down my own emotions. I am the ‘wish you would’ kind of guy. Anyone who wants to come my way and threaten me, they’re going to lose their eyes. But also, I’m the guy that can temper that down. I enjoy being a nice and caring person—that is who Rolando is—but I have razor-thin patience for anyone who wants to hurt me.

“That is what growing up in that kind of environment with my parents did to me.”

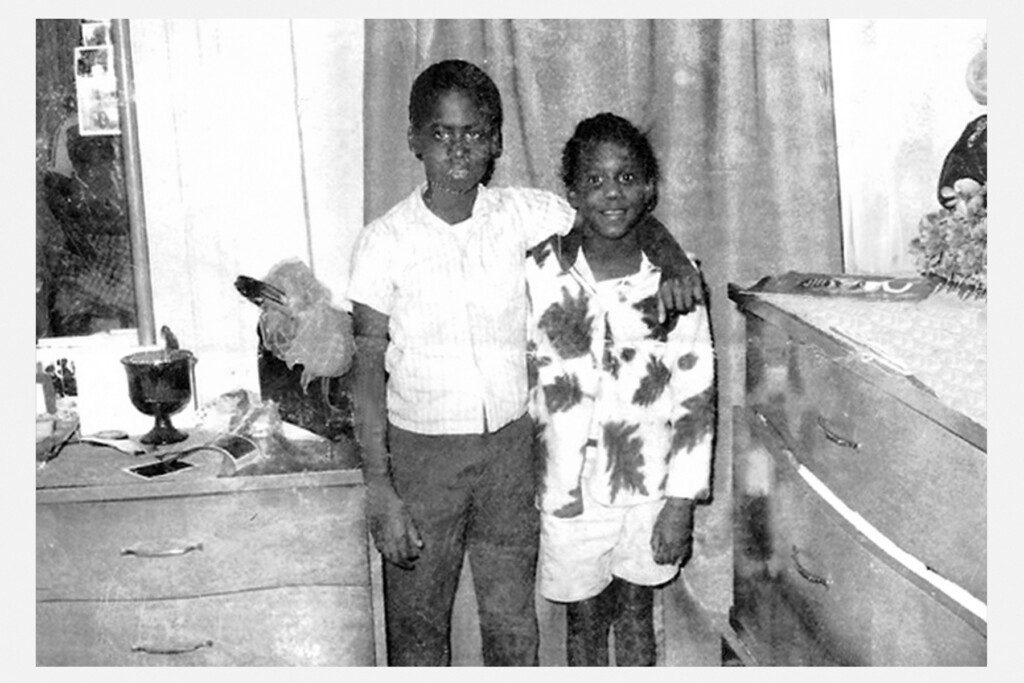

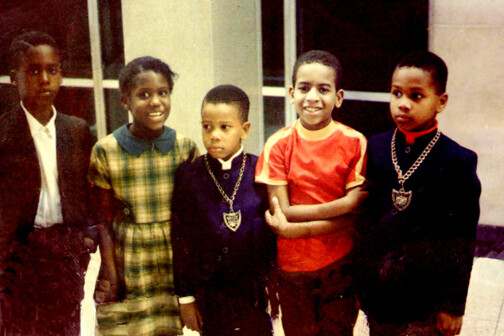

When he was 8, Blackman and his sister Angela left Panama after petitioning for emigration with student visas. Together, they left Panama on Aug. 25, 1967. The two siblings moved into their grandmother’s apartment in Brooklyn, near the East Flatbush and Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. In moving from Panama to Brooklyn, Blackman says, “I didn’t have a chance to let that part of me, my temperament, subside.

“In 1967, life in Brooklyn was so tumultuous, a jungle actually. Every time I looked downstairs, there was something going on. There were Black Power fights, there were Civil Rights fights, and Vietnam War marches; they had already taken John F. Kennedy and it was a year before the death of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy.

“As a young boy, trying to understand what was going on, things were difficult. Even navigating four blocks to school through the morass was a struggle. Getting to school and getting back home was a feat in and of itself. I had to play the game of, ‘Where is the gun? Where is it safe to hide?’ I had to map out where I was going before anything like that went down,” Blackman says.

As a native Spanish speaker, Blackman also had to overcome the language barrier. For three years, he went to school early at 6 in the morning to learn English. “I learned that the school teachers I had were really trying to teach us discernment. They were teaching us how to make it in the land of opportunity. I wanted to learn, but I was also afraid. So there was this duality to life. I knew if I didn’t graduate, that I would end up on the street.”

In 1970, after three years away from Panama, Blackman’s parents made it to Brooklyn and he moved into their new apartment. “They were still fighting like cats and dogs,” he says. “But by the time I turned 13, they had their final fight [and split up].”

Near Blackman’s new home with his mom was Ditmas Park. And what happened on the basketball court there would change his life.

“It was this park where I first tried to play the game of basketball,” Blackman recalls. “I brought a ball to the court and tried to play—I looked like everybody else. But when I checked in, I grabbed the ball and just ran with it. I didn’t understand why this defender was all up in my face. They yelled, ‘Traveling, traveling!’ Then I did it again and they yelled, ‘Man you suck! You can’t play!’

“So, being in New York, they snatched my ball and told me to the get the hell off the court. I sat on the sideline for three hours and watched them play. For years, I watched them play and just tried to emulate them. As a soccer player growing up, I didn’t know how to use my hands. It took me about a year of just watching them to figure out this ball in the basket thing.

Being in New York, they snatched my ball and told me to get the hell off the court.

Rolando Blackman on his first experience playing basketball

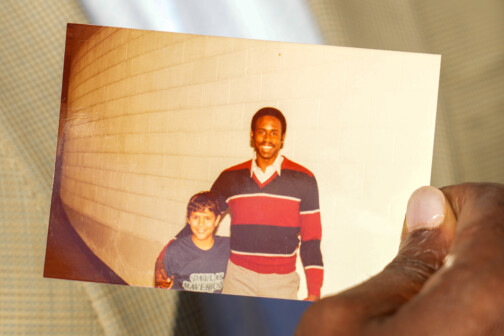

“During that time, I was taking taekwondo, I was going to church, and one Sunday when I was 11, I walked two blocks to Ditmas Park. This day was my enlightenment. I met my mentor Ted Gustus, who came up to the fence, as I watched through the other side, and asked, ‘Hey, do you want to play?'”

Those six simple words changed everything. “This was a supernova explosion of joy throughout my entire body,” he says. “‘Do I want to play? Of course I want to play!’ I told him. He told me to come around to the other side of the fence and asked me, ‘Can you play?’ Honestly, I told him, ‘No, I can’t play. I am just trying to learn the game.”

Blackman admits that he lived a life of separation. Until this moment. “I was always alone, avoiding the fool that would lead me to destruction,” he says. “That was until I found the people who were wanting to go in the same direction as me.

“Ted oversaw six courts at Ditmas Park. On court No. 1, the best players in the area played. On court No. 6, the kids who dribbled the ball off their shins played. Of course, I started on that court. But Ted told me, ‘If you come here every morning at 6 a.m., I can teach you the game.’

At 5 a.m. the next day, Blackman was up and ready. He made it to the court on time and Ted was there to teach him. Dribbling practice was first on the docket. “Right hand, left hand!” Gustus yelled. “Right hand, left hand. get your head up! Stationary! Move! Stationary! Move!”

“He took me from one level to another,” Blackman says. “And after school, I would come by the park and Ted was waiting there for me. At that point in my life I felt the most complete. At the same time, taekwondo was teaching me how to master my emotions. It taught me integrity and how to be calm. Life was pure bliss.

“I tried out for the 7th grade team, but I got cut. Eighth grade, I tried out again. Cut. Ninth grade came around, and I was getting better and better. I thought I was pretty good. But I got cut again. After that, I fell into an obvious deep depression.

I got cut again. After that, I fell into an obvious deep depression.

Rolando Blackman on getting cut from the junior high basketball team for a third straight year.

“I had this volcano inside of me; this thing was pain, I felt so much pain. But I just went back to work with Ted. As much as I was there, Ted was there. He was there for me all the time. And I came back the next year, in 10th grade, and I made the junior varsity team. I was so grateful. In 11th grade, I moved up to varsity and I remember getting my letterman jacket with the ‘V’ on it. When I put that jacket on I felt like Jackie Chan in Tuxedo. I felt like a superhero when I put that jacket on.”

On the court, Blackman was finally thriving. Off the hardwood however, hardships were swirling for him and his sister. “There were days where we ran out of food,” he says. “Some days, the only food I could rely on was given to me at school. I had to bring a meal ticket to school everyday, and I hid it in my underwear to make sure nobody would take it.”

Even if someone did mess with Blackman, he says his inner samurai was beginning to emerge. “What fueled my life, was getting cut three times,” he says. “By the time I was a senior in high school, I was First-team All City. Walking onto the court, I carried a double samurai. Don’t ask me anything on the court. Don’t ask me if we cool, don’t ask me how my mother’s doing, don’t ask me. That’s not what we’re here to do. And I knew they were asking me those things because they were trying to deflect my thoughts elsewhere. But I just told them, ‘What’s going to happen here, is I am going to whoop your ass.’ That’s the attitude I had.

“I can still feel it today when I walk into American Airlines Center. When I walk down the tunnel, I can still feel myself walking into the gladiator sphere. There is this other guy inside of me waiting to be released—there is Rolando and there is Ro, the athlete. But then I remember, ‘Man, I’m not playing anymore,'” Blackman laughs.

Nowadays, Blackman is aiming to foster the future of the game of basketball and help young generations of immigrants and minorities grow into successful professionals while navigating prejudice. “I have a deep understanding of what it takes as an immigrant to be able to move forward in the United States,” he says. “And especially if you have color on your skin. Because if you do have color on your skin, life is going to be tougher.

“The rules are not fair—at all. And we have to navigate those waters just to be seen as a viable person and an entity of light. The word fair is a fake word in the first place, it doesn’t exist as an adult. You always have to fight for that. At the end of the day, power comes when you stand up and speak up. The people that are too passive and too soft get eaten alive in this world. I call it gumption—I love that country word.”

Part of what Blackman preaches he learned from his former coach Jack Hartman and Mike Evans—a Kansas State standout in the 1970s and first round draft pick of the Denver Nuggets. As a freshman at K-State, Evans, a senior at the time, took Blackman under his wing.

“Mike was action-oriented,” Blackman says. “He was proud, stoic, and confident. I got to see another man who was ahead of me and learned from the consummate leader. By the time I was a sophomore, and Mike left, the leadership torch was passed to me. I had a great coach, Jack Hartman, who coached the great Walt Frazier at Southern Illinois. At each turn, he was always a great mentor to me. And he helped me ascend.”

And ascend he did. After averaging 10.9 points his freshman year in 29 appearances, he averaged 16.6 points, 4.6 rebounds, 3 assists, and 52.7 percent shooting his sophomore through senior seasons. He became one of just three players to be named Big Eight Player of the Year and to earn first team all-conference honors three times in a career. In 1995, he was inducted into the Kansas State Athletics Hall of Fame.

During his senior year at K-State, Blackman was invited to try out for the Olympic team. “Going up to Rupp Arena in Kentucky to try out for the Olympic team was special,” he says. “The best of the best where there. Guys were comparing stats, talking trash, and we were all trying to make the team. It was All-American versus All-American, and I was going to prove I belong. The next day, I walked down to see if I made the team—I was going to be pissed if I wasn’t on the list. But there I was: Rolando Blackman, Kansas State. The first day of practice, I sat at the end of my bed tying my shoe lace when it hit me: ‘I’m one of the best players in the world.’ But then the other guy suddenly came out of me and said, ‘What are we going to do about it? Man, we are going to whoop some ass, that’s what we’re going to do.'”

In 1981, the Dallas Mavericks selected Blackman with its ninth overall pick in the NBA Draft.

Blackman faced Michael Jordan and other greats, propelled by a ruthless energy—and even some graphic imagery. “Everybody get their boot ready because we’re gonna put our foot up our opponent and make it disappear,” Blackman remembers telling in his teammates. “And if you can’t get to that point, then you can’t make it to the heights. I can’t look Michael Jordan in the face knowing that I am not clicking on all cylinders. I wasn’t going to let anybody—even if it was your grandmother—win a damn thing. And I had to have my boys help me. We can’t do anything alone in life. I had to play smart, I had to make sure to throw a couple of elbows, make sure to incorporate the whole squad—that is what warrior mode looked like.

“In the 1980s I shot 50 percent from the field. We were all hand-checking guys, slapping wrists, slamming each other’s asses on the ground. All throughout the whole decade. I was getting poked in the eye and all kinds of hidden stuff, too. And I was still sharp—50 percent. Why? Because I can shoot, period. And I was tough. Whatever my opponent gave me, I was going to give it back. And I used to love giving it back. I see your neck, I see your body, and that is exactly where these two samurai swords are going.”

Off the court, Blackman put away his ruthless energy. “I’ve been doing community service ever since I got to Dallas in 1981,” he says. “It was always something that I did because Ted did that all throughout the time he coached me. He took us all around New York and we were going to different hospitals and this, that, and the other.”

It wasn’t until 1986, that Blackman was finally granted U.S. citizenship—for nearly 20 years he thought he was already a citizen. “Growing up in the United States as young boy, not knowing anything, every form I ever filled out, I always filled in ‘United States citizen,'” Blackman laughs. “So, when I tried out for the USA Olympic team, their records showed that I was a U.S. citizen, but I wasn’t. I didn’t even find out until years later. Not until 1986, did it become official. I thought because I got on that big ol’ airplane to take me to America, that I was a citizen.”

Today, as the vice president of corporate relations for the Dallas Mavericks, Blackman has put away his samurai sword. He says it has saved him countless heartbeats. But that other guy—Ro, the athlete—will always be inside of him somewhere. “I can still use my 10 years of experience as a black belt,” he says. “But, nowadays, I enjoy being the nice guy much more.”

Author