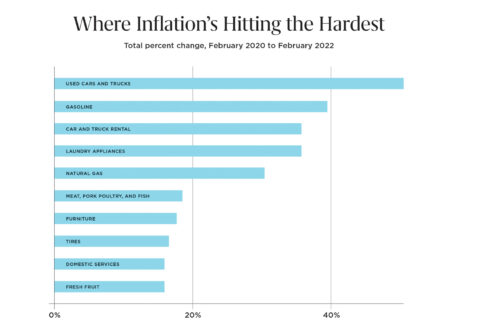

We’ve heard about it repeatedly, from friends, family, neighbors, political leaders, and expert sources. Nearly everyone has felt the impact of inflation. For the 12 months ending in February, the Consumer Price Index jumped 7.9 percent—the highest shift since the early 1980s. Stretch it out for two years, and prices were up 9.7 percent, with some consumer goods, including meat, furniture, tires, and fruit, experiencing particularly impactful jumps (see chart).

Texans shouldn’t expect to be spared the inflationary fires. They produce and consume in an increasingly interconnected world, where national and global trends go a long way toward setting the prices of goods and services.

The COVID pandemic contributed to the limited supply and resurgent demand that has increased consumer goods prices. Interrupted or overburdened supply chains created delays in delivering consumer goods and inputs; global oil and gas prices sank then soared as the pandemic whipsawed energy producers; supplies took another hit when Russia invaded Ukraine in February; COVID left many workers hesitant about returning to jobs, leading to labor shortages and wage hikes. These market factors create short-term impacts on some prices—whether permanent or temporary—but markets will eventually sort them out by reducing demand or increasing supply.

Broad and sustained price increases—true inflation—come from policies leading to excessive money creation. Essentially, there is too much money chasing too few goods. Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman made this point in his dictum: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Since COVID hit the United States in February 2020, Congress has been spending recklessly to keep the economy afloat. An accommodating Federal Reserve, aiming to maintain low-interest rates, has also flooded the economy with new money via stimulus packages and other means. As a result, the broadly defined money supply has shot upward by an unprecedented 41 percent. For Texans, Friedman’s words mean that today’s inflation isn’t a problem of our own making, and there’s little the state’s business or political leaders can do to lower it.

Only Americans born before 1965 could have mature memories of the last time the country faced inflation at a level comparable to current rates. To bring prices down in the 1970s and 1980s, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker took harsh actions to wean the economy off easy money by dramatically increasing interest rates—so much so that the country tipped into a deep recession.

Texas was hit particularly hard by the aftermath of inflation during that time. After riding the benefits of high oil prices throughout the 1970s, the state’s economy tanked as petroleum prices dropped by 50 percent. While the rest of the nation was recovering from the recession, Texas economic output declined by close to an additional 3 percent between 1986 and 87, taking a severe toll on the banking and real estate sectors. Unemployment peaked at 9.3 percent in March 1986.

Thus, history tells us that inflation isn’t likely to be subdued without pain, including slower growth, lost jobs, eroded wealth, and higher borrowing costs. What nobody knows yet: How much pain will it take to rid the economy of inflation this time?

So far, the Fed has taken a small first step toward fighting inflation, raising interest rates a quarter of a percentage point in March. Additional rate hikes are no doubt on the way. Now, the central bank faces a precarious challenge in restoring price stability—move too timidly, and inflation may continue to rise; move too forcefully, and risk triggering a national recession.

How would a downturn impact the Lone Star State? Today’s Texas economy is highly diverse—more like the rest of the country in its mix of industries and jobs than it was in the ’80s; it is not nearly as dependent on oil and gas as it once was, meaning it benefits less from rising energy prices but is not as vulnerable to falling energy prices. Our research shows that Texas also ranks fifth among states for economic freedom—a short-hand term for a predilection toward giving markets and the private sector the leading role in the economy. This has helped the Texas economy grow faster than the rest of the country for more than two decades, and it has helped keep recessions milder and shorter.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has pointed to inflation flare-ups that didn’t lead to recessions in 1965, 1984, and 1994. But none of these years followed periods of inflation as high as it is now—not to mention war and supply-side challenges. If Texans are worried, they have good reason.

W. Michael Cox is a professor of economics and Richard Alm is a writer-in-residence at the Bridwell Institute for Economic Freedom at SMU’s Cox School of Business.