Doug Jones knew very little about the commercial real estate business when he retired his Army Ranger fatigues in 2014. But the West Point grad had learned plenty about resourcefulness, servant leadership, and making decisive moves during his military career. He performed entry-level tasks at Cushman & Wakefield as a rookie broker for months before being given larger roles. Today, he oversees the firm’s Dallas operations and is one of the global company’s youngest leaders. Similarly, former Navy SEAL platoon commander and NASA Chief Astronaut Chris Cassidy had no related experience when he was asked to serve as president and CEO of the National Medal of Honor Museum Foundation, which will open in Arlington in 2024. “I don’t think I could even spell museum when I was first told about the job,” Cassidy jokes. But, having led precarious missions beneath the sea and beyond the ozone, he was confident that he’d be up to the challenge. Bob Pragada at Jacobs, Christine Peyton at Amentum Aviation, and Scott Rowe of Flowserve also credit their military experiences with shaping their leadership styles and propelling them into the C-Suite. Here, they share their remarkable stories of bravery, fortitude, and adventure—and the lessons they learned along the way.

Chris Cassidy

President and CEO, National Medal of Honor Museum Foundation

U.S. Naval Academy, Class of 1993, U.S. Navy SEALs Team, 1993–2003, NASA, 2004–2021

“Holy shit,” Chris Cassidy thought to himself in 2013 as he tethered to the International Space Station for a spacewalk 227 nautical miles above the earth. He was watching his partner Luca Parmitano’s spacesuit fill up with water—1.5 liters worth, to be exact. Cassidy, a former Navy SEAL, had previously captained mini submarines, led SEAL Team 3 as one of the first teams to deploy in Afghanistan following 9/11, detonated piles of Al Qaeda intel, and never once lost a single SEAL team member he managed. But, now in the vastness of space as the NASA Chief Astronaut—the farthest away from the battlefield he had ever been—death was on the prowl.

Cassidy acted quickly, thrusting himself over to his partner, and the team within the space station prepared the airlock—the safe zone—for Parmitano. Just in the nick of time, Cassidy hauled his partner into the airlock, and the team safely removed his flooding helmet. The moment—captured in the Disney+ series Among the Stars—is something the now-president and CEO of the National Medal of Honor Museum Foundation in Arlington thinks about to this day.

“I say this all the time: ‘If you see something that is wrong, you need to act,’” says Cassidy, who spent 10 years in the Navy and 17 years with NASA. “In this case with Luca, even as early as a week prior on another spacewalk, we noticed indications of water, but it didn’t make any sense to us, so we brushed it off. Then earlier on the same day as the spacewalk incident, there were small indications that something was wrong with the suit. Things weren’t seeming right, but it was so easy at the moment to just press on and do our jobs.”

Read More: Chris Cassidy on surviving “hell week.”

When Chris Cassidy told his parents he was going to be a Navy SEAL during his final year in the academy, his mother asked, “What are you going to do after you’re done? Be a mall cop?” But Cassidy quickly proved that was never in his plans. “In 1993, when I went to BUD/S (Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL school), we started with 120 people,” Cassidy remembers. “Seventeen of us graduated. The training is generally six months long, broken up into three phases. The first phase is the weed-out phase, known as hell week. The second phase is all about diving. And the third phase is all about land warfare, shooting, detonation, and navigation. To this day I am most proud of finishing as the honor graduate of BUD/S.”

When Cassidy, an MIT grad, was approached about the opportunity to lead the National Medal of Honor Museum, the opportunity felt right. “When I retired, I thought long and hard about what it was going to take to fulfill my sense of service. When I met with our board, I realized there is a whole city, state, and country that supports this mission.” The 101,000-square-foot project will break ground this month.

For Cassidy, the challenge of raising $200 million to construct a museum—a goal the organization has nearly accomplished—seemed overwhelming at first. But he quickly realized there were similarities to past missions. “‘I don’t know how to raise $200 million by myself,’ I thought when I started,” Cassidy says. “But the fundamental aspect of every job is people. Whether I’m on a battlefield, flying space missions, or building museums, it’s all about the people. When I was in the military and in government, I thought that was just how it was in those lines of work. But when I got to Arlington, I realized great people are crucial to all great accomplishments.”

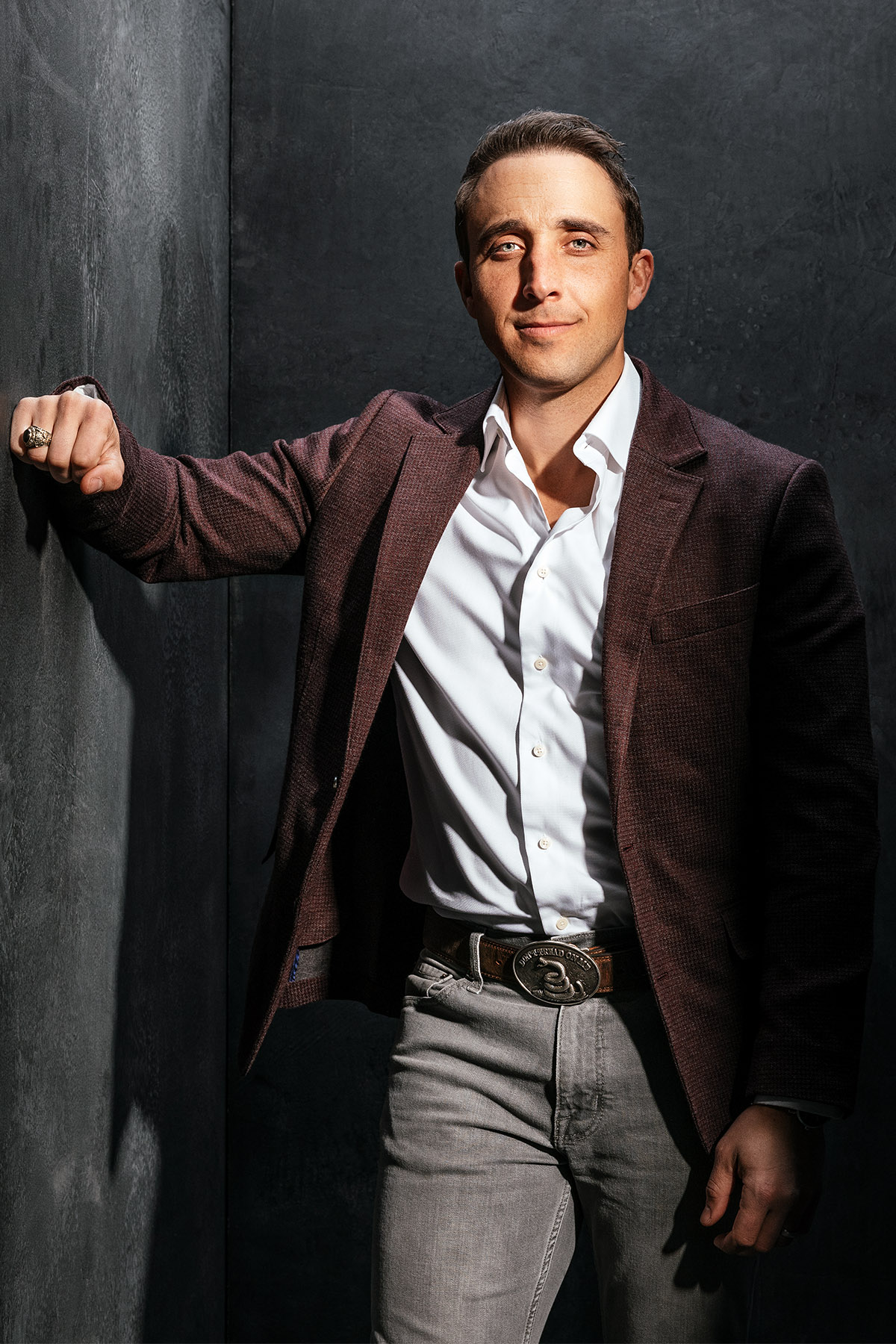

Doug Jones

Managing Principal, Cushman & Wakefield

U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Class of 2008, U.S. Army, 2008–2014

Having to retake a land navigation test while working through Army Ranger school, Doug Jones felt lost. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘My girlfriend will break up with me, my parents will disown me, my friends will laugh at me.’ I felt like a failure,” Jones says. Standing deep in the woods, trying his best to pass the five-hour makeup test, he sulked, convinced he was going to fail a second time. If a trainee fails twice, he or she is sent packing.

“I had never failed land nav before this,” Jones says. “And in my makeup test, I found myself collecting three of the six points I needed to collect with only 30 minutes left. Mentally, I had already failed. As I walked back to the starting line, thinking it was too late, I saw a flash of light out of the corner of my eye. So, I run to it, and it’s a point, but it isn’t mine. It does tell me, though, where I am on the map. So, I strap up, get serious, get accurate with my navigation, and I make it back with all my points and pass the test.”

Read More: How Doug Jones’ life changed on a ruck march

Doug Jones was two weeks into Beast Barracks—an initiation program prior to joining West Point—when his leadership style began to take shape. Amidst a ‘ruck march,’ a grueling, fast walk over rough terrain wearing a backpack of at least 35 pounds, his platoon leader commanded a halt. “He comes up to me and says, ‘Take a seat, and take off your boots and socks.’ I do as he says, and he looks at my heel, and asks, ‘How are your feet?’ I answer, ‘They’re fine.’ He told me, ‘OK. If you start to get hotspots, powder up and change socks.’ I got up, and we kept moving. But in that moment, he stopped and taught me a very specific lesson: servant leadership. That is the foundation for my genuine care for people today.”

Going into the test, Jones thought the course would be the same as the year prior; it was not. “We thought we were running to the same points, so we didn’t trust our map or compass,” he says. “I learned that day I need to wholly trust the information I have available, trust my inner compass, and follow the plan that is in front of me.”

Jones says lessons from his last mission set the tone for his career trajectory in commercial real estate. “My last assignment in the Army was in company command,” Jones says. “I was responsible for 250 soldiers and a $100 million property book, which was not my forte—property being the things that a unit needs to deploy, not property like real estate—but things like a Bradley Fighting Vehicle, armory, and all the little nuts and bolts. Today, I know that leadership is not a salad bar of things where I get to pick and choose what’s fun. It’s digging in and doing what I can to help Cushman & Wakefield win, no matter what it is.”

The leadership experience helped him land his current position—managing principal of his firm’s Dallas office, one of the largest and most active in the company. He also serves as executive director of Cushman & Wakefield’s Military & Veteran Programs. “I have the best of both worlds,” Jones says. “Being able to lead our incredible team here in DFW while serving the military community, transitioning veterans, their spouses, and their families, is a true blessing.”

Although at one point he thought he was facing inevitable failure, his military experiences taught him to rise above. “West Point and active duty gave me my integrity and my character,” Jones says. “It taught me that we, as people, are way more capable of accomplishing greatness than we might think.”

Christine Peyton

Senior Vice President, Amentum Aviation

U.S. Air Force, 1991-2015

Twenty-four-year Air Force veteran Christine Peyton served stateside, throughout the Middle East, and in South Korea as an Aircraft Maintenance Officer on F-15, KC-135s, C-5s, F-16, C-130s, and A-10s. She also served as an intelligence officer and helped fight human trafficking. But what stands out is the agony of losing fallen colleagues–soldiers she refers to as her kids. All were killed by ethereal ammunition. “I had six airmen commit suicide in the span of two years on active duty, and that was very difficult to deal with,” she says. “One of the biggest problems in the Air Force—and across all the services—is the number of suicides our teams experience.”

A retired Lieutenant Colonel, Peyton was trained to be tough since her childhood, but breaking the news to the families of the airmen was nearly unbearable. “Everything about it was devastating,” she recalls.

Seven years after retiring from the Air Force, Peyton is leading a new type of team at the Fort Worth office of Maryland-based Amentum Aviation, where she serves as senior vice president. While on active duty, she made it her mission to “help as many people as she could.” And today, within the C-Suite, she continues to lead with that philosophy.

“As a leader, you need to listen to people—not just hearing, but really listening,” Peyton says. “Look at their body language, look at what they’re doing in their life; if they come to your office to talk to you, make sure you’re fully dedicated and 100 percent there with them. Because if you’re not, you’re going to miss the warning signs.”

Read More: Christine Peyton’s early years working on a lobster boat

Christine Peyton came of age on a lobster boat off the coast of Wells, Maine, hearing stories about her father’s Navy days. She earned a dime per lobster processing the crustaceans, but it was the military seed that was planted that proved to be more valuable. Today, decades after those first moments at sea with her father, the pride lingers on. “I can never put into words how creative, driven, and dedicated the airmen I served with were,” Peyton says. “It didn’t matter if we were under the gun to launch an entire fleet of aircraft for a hurricane evacuation, sending our aircraft overseas to support our allies in times of need or just flying training missions, everything we did was done with expert skill, precision, and professionalism.”

It’s a dedication Peyton—who was one of only a few female aircraft maintenance officers in the Air Force in the early ’90s—proved over and again while in the academy and on active duty. Her leadership style greatly evolved in the ensuing decades.

“It wasn’t easy being a female in aircraft maintenance in the early ’90s,” she says. “When I enlisted, I was frustrated with outdated policies, procedures, and culture. I wanted to change things for the better. It may have been a bit naïve of me, but I had to try. When I finally became a lieutenant, I was a bull in a china shop. I wasn’t going about change in the right way.

“Thankfully, I had a very seasoned chief master sergeant put me in my place,” Peyton says. “I was raw early in my career and needed a major correction. It made me step back and reflect on what kind of leader I wanted to be. I wanted to be a leader who listened, encouraged, and brought out the best in her troops.”

It’s a philosophy she has taken with her to Amentum Aviation, which provides maintenance, logistics, flight operations, and training for both manned and autonomous aircraft. “This year, I’m striving to mentor my folks so I can push them up into positions where I know they can be effective.”

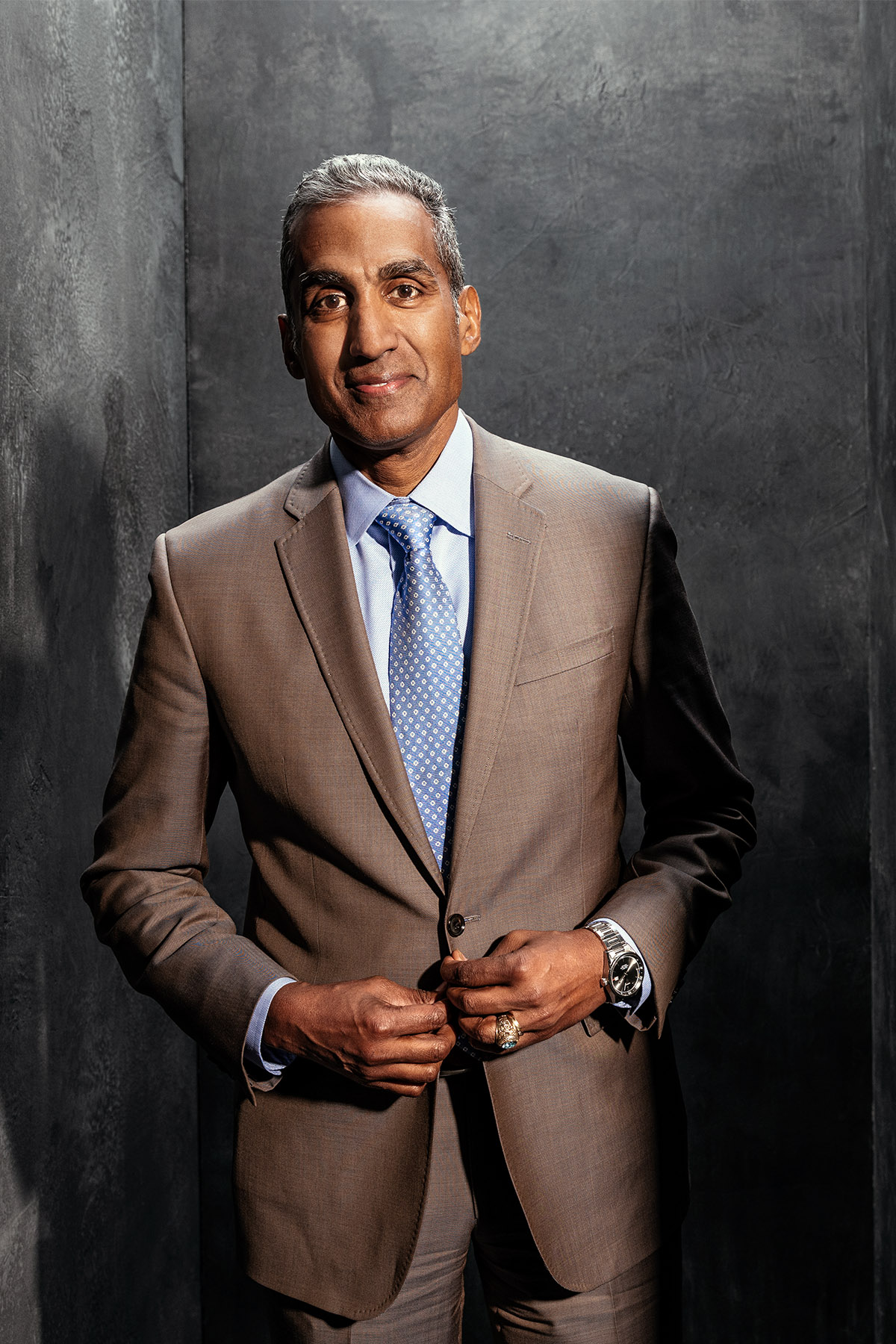

Bob Pragada

COO and President, Jacobs

U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1990, U.S. Navy 1990-1999

When Indian American Bob Pragada began attending the Naval Academy in 1986, there were no classmates who looked like him or had the background he did. He didn’t think much of it when he graduated in 1990. That moment would come 21 years later when he was having dinner with his son after a baseball game in Myrtle Beach.

“When we left the restaurant, a young Indian American kid had a Navy tracksuit on,” Pragada says. “I stopped the young man and asked, ‘What year are you at the Naval Academy?’ Looking at me, he says, ‘I’m a sophomore.’ Then he said, ‘Sir, can I ask who you are?’ I said, ‘My name is Bob.’” The student instantly knew with whom he was speaking.

Afterall, Pragada, chief operating officer and president of global engineering firm Jacobs, was the second Indian American to graduate from the United States Naval Academy. The first came just one year prior in 1989. (Today, there are 39 Indian Americans attending the US Naval Academy.) “At the time of graduation, I didn’t think my accomplishment mattered,” Pragada says, choking up. “But now, realizing it has helped pave the way for generations to come is one of the most satisfying things.”

Read More: The movie that sparked Bob Pragada’s military career

The 1982 movie An Officer and a Gentleman mesmerized Bob Pragada’s immigrant mother. “She came home after seeing the movie and told me, ‘You should go to Annapolis,’” Pragada remembers. “When I asked her why, she said, ‘The uniforms!’” And so, the young Pragada went off to the local library in Chicago to study up on the Naval Academy, not realizing that he’d eventually go where just one Indian American had gone before. “I was just trying to do some good,” Pragada says. “And that has been ingrained in me since a young boy. In my time in the classroom, on the rugby team, and in training, I learned that life is all about making whatever team you might be on at any given moment, the best possible team

it can be.”

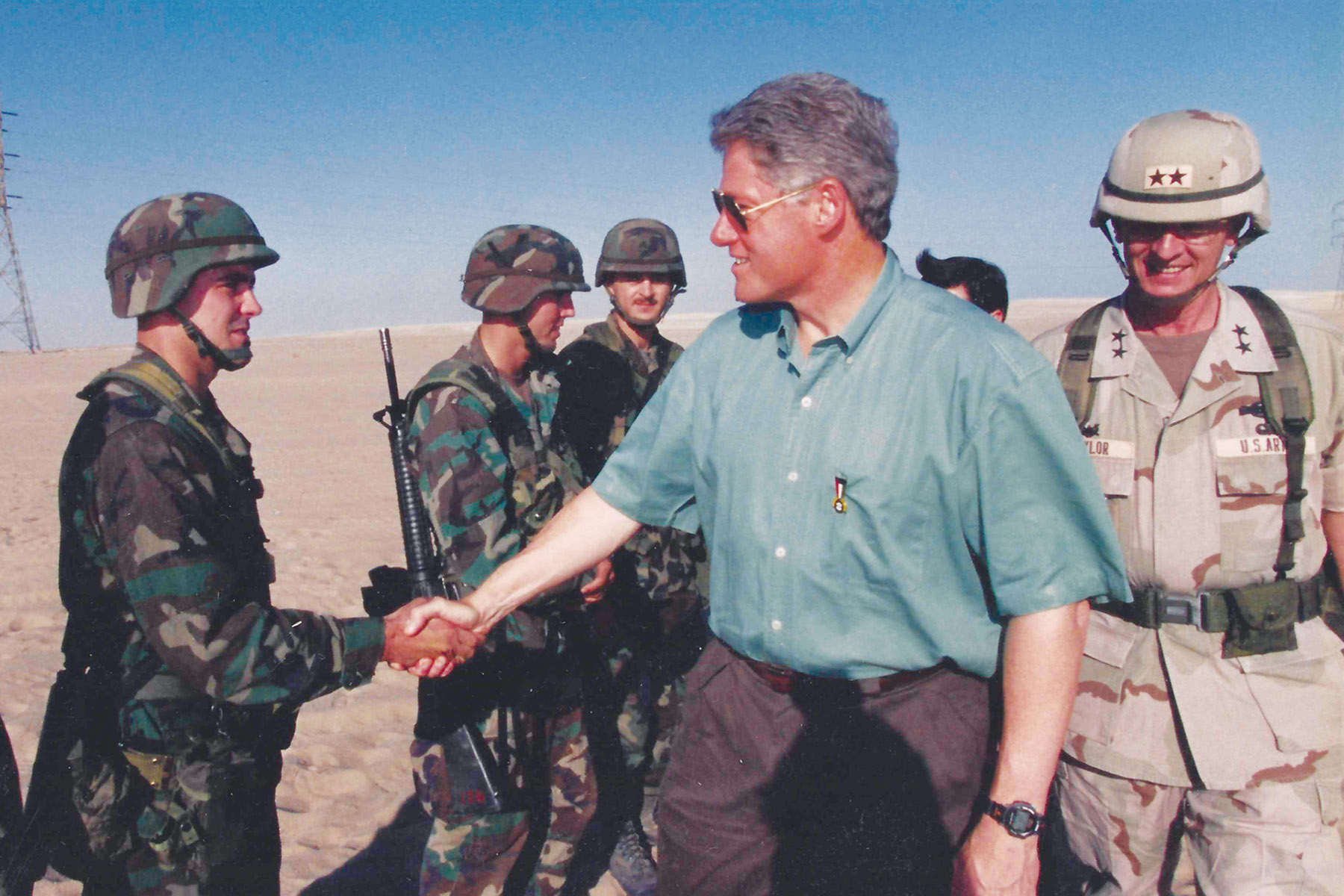

Pragada went on to fulfill, in his eyes, his most significant duty alongside President Bill Clinton in the White House Military Office at Camp David, the retreat for the president of the U.S. located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland.

“Working Camp David is service to the country defined differently than building a bridge or setting up a base camp or flying a plane,” Pragada says. “It’s service in the sense that our job was to put the First Family in an environment where they felt comfortable.”

Early into Pragada’s post at Camp David, he was assigned to look out for Ted Kennedy as Cabinet members and key senators visited for a delegation. Immediately, Pragada knew this assignment was written in the stars. His father, an engineer in India in the early ’60s, came to the U.S. to study in a graduate program and work for NASA via a program sponsored by John F. Kennedy. “The Pragada family owes our American citizenship to your family,” Pragada told Kennedy. And just like that, a bond was formed, leading to Pragada sitting with America’s most powerful as one of the few military reps at the discussion.

It’s a personal moment that has stuck with him to this day as he leads Jacobs’ worldwide operations. “My service taught me to keep people first,” Pragada says. “I could say we have the best engineers, best scientists, best technicians, best support staff, and we do,” Pragada says. “But how we reach our goals is through our culture—a culture that loves every single person on staff regardless of gender, who you love, and where you’re from.”

Scott Rowe

President and CEO, Flowserve

U.S. Army, 1993–1998, U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Class of 1993

A month after Scott Rowe showed up in Fort Stewart, Georgia, as part of the U.S. Army Intelligence team in 1994, he was deployed to Kuwait. “The place was a war zone,” Rowe says. “And the reality of what happened in the invasion of Iraq into Kuwait set in—we were in the middle of bombed buildings and artillery shells. But the most rewarding part was making sure they had enough military might to defend themselves [moving forward] … we essentially liberated an entire country.”

Rowe didn’t realize it at the time, but his country-building experiences in Kuwait would give him the confidence and skills to lead and implement a $14.8 billion corporate merger in 2016, two decades after he retired from the Army. Six months after being promoted to president and COO of Cameron International, oilfield services giant Schlumberger made an offer to buy the company, a provider of flow management equipment. “It was one of those situations where you go, ‘Really? Like now we decide to sell the company?’” Rowe says. “But when I think back to the operational manual in the military, it is about evaluating different courses of actions. And that’s exactly what we had to deal with in the Schlumberger offer. $14.8 billion is a big number. It was an uplift on our stock about 30 or 40 percent. And we had to evaluate if we wanted to take the offer from Schlumberger or if we wanted to work out a plan that, theoretically, could get us to that same value. We evaluated and discussed, and because the offer was cash-based, we made the sale.”

Read More: A Ranger school exercise that shaped Scott Rowe’s leadership skills

The longer Scott Rowe is away from the military, the more he appreciates what it did to shape his leadership skills, he says. A peer review exercise in Ranger school taught him about building trust with teammates. “We had a squad of 10 people, and we ran around the woods for 10 days with no food and no sleep. Afterward, we rated each other on various skills like assault and defense. And then, at the very end, the last thing we did as a team was rank our peers strongest to weakest, one through 10. The lowest ranking person gets kicked out, and they don’t return. I see the same thing in business. If leaders aren’t building their teams by passing along inspiration for workers, it is not sustainable, and you will fail.”

Roughly a year later, Flowserve recruited him to become its new president and CEO. “I think the military teaches you to expect the unexpected,” says Rowe. “One night, I got a piece of information on the Iraq border that said, ‘There’s going to be a truck driving your way, in the next six hours, that has significant explosives in the back. And they’re a participant in X organization.’ I received a lot of intel, but this one was an ‘Oh, my god, this is real’ moment. Sure enough, three hours later, a truck rolled into our checkpoint with the license plate on the piece of intel, and there was a bunch of C4 explosives in the back of the truck with two terrorists at the wheel. We didn’t fully know what their intentions were, but it wasn’t good.”

It’s a save Rowe is proud of—and an experience that helped build his leadership skills that he now puts to work at Flowserve, which generated $3.7 billion in revenue in 2020. A primary focus for the company going forward is environmental emissions. “In 2022, we’re going to diversify, decarbonize, and digitize,” Rowe says. “We will help customers with their operations, so productivity, reliability, and decarbonization are driving CO2 emissions down and driving energy use down.”

Get the D CEO Newsletter

Author