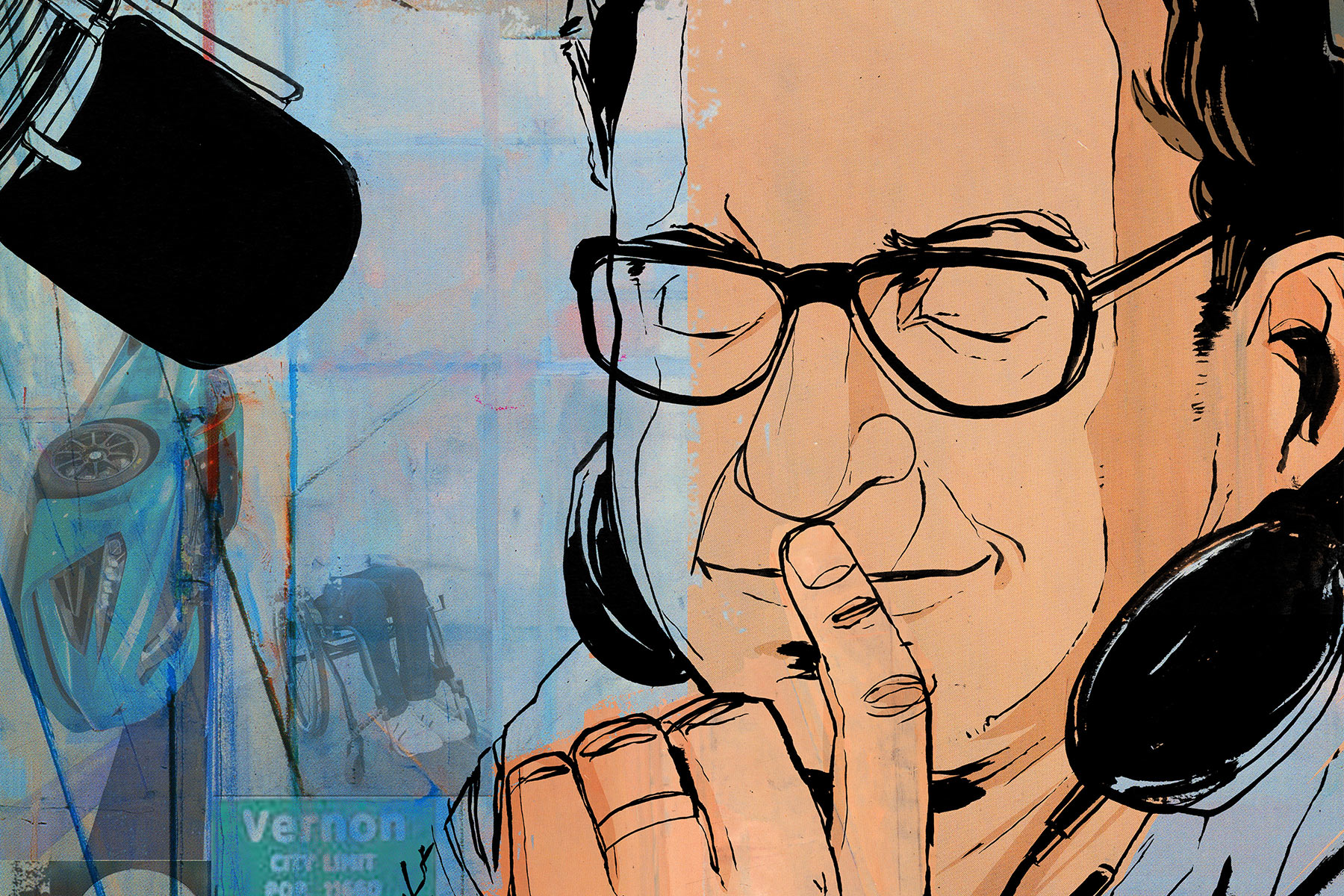

Seventeen years ago, John Clay Wolfe lay in a hospital bed, trying to absorb the news that he would never walk again. Down the hall, between monitors and other equipment, a fax machine buzzed with divorce papers from his soon-to-be ex-wife, who was leaving him after learning that she’d have to be his caretaker. Just days later, on Christmas Eve, Wolfe says his ex-wife brought a .45 pistol to his room at Baylor University Medical Center as he recovered. Wolfe’s friends were visiting; they intercepted the bag before he looked inside and removed a box of ammunition. Years later, they told him about the bullets, making the intent clear to Wolfe, who didn’t fully understand the callousness of the gift at the time.

Months later, while still in recovery, Wolfe received a call from his banker about irregularities in his business finances. He’d come to learn that his controller had been stealing from the company while he was laid up. The fallout would bankrupt the enterprise and cause Wolfe to liquidate many of his assets. The physical, relational, and financial rug had been violently ripped out from under him, but Wolfe did not respond with despair. He likens his attitude at the time to a scene in Forrest Gump where Lieutenant Dan is screaming at a hurricane as it threatens to sink the shrimp boat. “You call this a storm?!” he shouts. “It’s time for a showdown! You and me! I am right here. Come and get me!”

Wolfe says his mindset was, “You are going to have to kill me. I have a mission to come back. I might as well be dead, so let’s see if we can pull this off.”

And pull it off, he did. Wolfe’s wholesale car business, GiveMeTheVin.com (GMTV), will make $1.6 billion in revenue this year and is one of Tarrant County’s most significant privately held businesses. It’s the largest car wholesaler in the country, selling an average of 1,000 used vehicles to dealerships around the country every week. The story of how Wolfe bounced back is one of grit, determination, tragedy, and triumph.

From Fort Worth to Wall Street

Wolfe’s parents split when he was 3 years old, and he lived a childhood divided between ranch life with his father, who owned a construction business, and a country club existence with his socialite mother in Fort Worth. At the age of 9, Wolfe was driving a K5 Blazer around the ranch and to a local store. When he was 10, he was featured in Texas Contractor magazine operating a piece of heavy equipment. “Today, I’d probably get arrested,” he quips.

His mother went on to marry an investment broker and split her time between Aspen and Connecticut. His stepfather introduced Wolfe to the trading floor. The action, deal-making, and energy of the NYSE lit a spark in Wolfe, but despite an internship in the industry, a Wall Street career never materialized.

Back in Fort Worth, Wolfe showed an early proclivity for vehicle deals, buying and selling a Blazer, Camaro, BMW, and truck in high school, upgrading and turning a profit each time. He worked at a Tarrant County Ford dealership between high school and college—his fir t official gig in the car business. Within 60 days, he was named the dealership’s salesman of the month, and a particular aspect of the industry had caught his attention.

Customers would trade in their vehicles, and the dealership would sell the car to a wholesaler, who would eventually sell it back to other dealerships who thought they could turn a profit. Wolfe was intrigued. Today, he sees that GMTV is a combination of Wall Street and his experience at the dealership.

But it was the gridiron that would call him next, playing defensive end for Southern Methodist University in the years following the death penalty that erased what had been a powerhouse program. In his early years at SMU, however, he learned that his father could not continue to pay for his education. Between financial hardship and getting blown out on the football field, it was dark times for Wolfe. “Humbled is not a good word,” he says. “Defeated is better. I needed to get away from that and go do something positive with my life.”

He hung up his cleats and used a Pell grant and a loan from his stepfather to open the Plaid Pig, a pub in Fort Worth. “For the Pell grant people, I didn’t put on the application that I wanted to open up a bar,” he laughs.

After graduating, Wolfe took another entrepreneurial pivot and was awarded a patent for what he calls an “automated telenet computer.” He reached out to potato magnate J.R. Simplot in Idaho after seeing him on the cover of Fortune magazine. Simplot’s company had just purchased tech company Micron Technology. After making numerous calls and eventually sending flowers to Simplot’s secretary, he got the billionaire on the phone. Wolfe gave Simplot his pitch. “I don’t know the difference between computer chips and potato chips,” Simplot told him. “But I can tell somebody who’s got some spirit.”

Simplot flew his plane to Texas, picked up Wolfe, and took him to Idaho, where he was introduced to executives. They got to work launching what Wolfe describes as an early version of an internet pay phone hub, with public terminals where people could check their email. Unfortunately, Larry Ellison at Oracle had been working on the same idea and beat them to market in the late ’90s, and the project was scrapped. It was back to the drawing board for Wolfe.

Losing Everything

With nothing else to do, Wolfe got back into the car business, working for his cousin who had a small mechanic shop and used car lot. As a dealer, he attended a live auction, where wholesalers would sell vehicles to dealerships that thought they could make a profit on the car. The fast-paced events were noisy, with auctioneers and dozens of lanes of cars moving through an open-air pavilion of sorts and licensed dealers bidding on cars. At that moment, Wolfe saw his love of cars, his deal-making prowess, and his passion for live-action come together. “I just couldn’t believe my eyes,” he says. “I fell in love with it right then.”

But he wanted to do it better. His idea was to make the process more sophisticated and create a commodity-driven market. In 1997, Wolfe launched a wholesaling business, buying and selling used vehicles via auction, and found he had a knack for the hustle the industry required. At 22, he was making $300,000 per year. He made a million dollars the year he turned 27 and bought a few car dealerships as investment opportunities by the age of 30.

Wolfe was on top of the world at 32 in December 2004 when he had a horrific motocross accident near his ranch in Nocona. He snapped his spinal cord and was told that he would be in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Wolfe spent months in the hospital. During that time, his wife of eight years, with whom he had a 1-year-old daughter, filed for divorce. He received the settlement papers while he lay in a hospital bed. Then came the “gift” of the gun on Christmas Eve.

Determined to beat the odds, Wolfe forged ahead with physical therapy. One day when he was in a pool doing rehab at Baylor University Medical Center, he noticed a trace of movement in his leg. It wasn’t much, but he could move it less than an inch either way. “Maybe I can work out of this,” he thought.

Just as he was experiencing a glimmer of hope, Wolfe got a call from his banker about some irregularities. He knew something was up when he answered to a room full of people on a conference call. The cash flow wasn’t lining up, and creditors were calling. Through an internal audit, he would later learn that his controller had been colluding with people outside the company to sell vehicles for a fraction of what the records were reporting. She was obscuring individual sales by lumping them in large groups. In one deal, instead of selling dozens of cars to a dealership for $180,000, the wholesale company received only $50,000.

Transactions were going through, and money was collected, making the scam challenging to detect. Eventually, a forensic auditor had to piece the puzzle together with the dealerships’ transaction logs and Wolfe’s wholesale company’s records to see the malpractice. The case went to court in Wilbarger County in North Texas but never made it past a grand jury. “This is going to be hard to educate a rural jury,” the District Attorney said at the time. “It’s just too deep of a paper chase.” Wolfe wouldn’t be able to recoup the money, but the investigation wasn’t a total loss. He hired the forensic auditor who got to the bottom of the embezzlement and still employs him today.

In the meantime, Wolfe was forced to liquidate his considerable assets—his ranch, a property he owned in downtown Fort Worth, his private plane, and all but one car dealership near the Red River in Vernon. In this moment of financial, physical, and relational ruin, Wolfe found himself yelling at the storm.

As a defensive lineman in college, Wolfe’s job was to give all he had to get to the quarterback, no matter how many times he was knocked down. It takes a commitment and a fierce drive. When Wolfe looks back on this moment, he credits football for programming him to continue pushing in life and business, just as he had between the hash marks. “It’s taking that kind of mentality to get back to work, so I could get back what I lost,” Wolfe says.

Eighteen months after the accident, he was walking with the help of a walker. This past December, Wolfe celebrated 17 years of walking on his own.

Clawing His Way Back to The Top

Wolfe’s remaining assets kept him in business, and he took his small-town dealership and innovated once again. With his physical capabilities still limited by a wheelchair, he shifted his attention to radio. To drive traffic to his dealership, he bought some time on a local radio station for a Saturday morning show where he made a unique pitch: Wolfe dared listeners to call in and give him the VIN on their vehicle and describe it, and he would make them an offer sight unseen

The entrepreneur was doing in his brain what is now a standard process of entering a vehicle’s information and receiving a bid online. But Wolfe could see the market before it happened, and he knew precisely the kind of margins he could turn on which cars.

In his early days in the business, Wolfe would spend time memorizing the numbers of the car books, recalling the value of a 1998 Chevy with encyclopedic accuracy. Once on his radio show, he made offers for 23 cars in just five minutes. Later, he would connect with the largest wholesaler of vehicles at the time, who would mentor Wolfe into becoming what he is today.

I might as well be dead, so let’s see if we can pull this off.

John Clay Wolfe

As his radio presence grew, Wolfe shifted to creating a show of his own—somewhere between Howard Stern and Dallas’ The Ticket—and getting other car dealerships to sponsor his time on the air. Today, the four-hour John Clay Wolfe Show is broadcast on Saturdays on dozens of stations across the country and attracts a half-million listeners each week.

“He’s an incredibly driven, passionate, and smart businessman,” says Otto Padron, president and CEO of Meruelo Media, which owns KLOS in Los Angeles, a rock station that broadcasts Wolfe’s show, which can be heard locally on Lone Star 92.5. “He is a driven perfectionist. He is constantly looking to do a better job at every turn.”

While keeping his radio show going, Wolfe formed GMTV to generate more revenue. In 2021, the company sold 47,000 cars via auctions in Dallas, Los Angeles, Chicago, Orlando, Nashville, and Pennsylvania, generating more than $1 billion in revenue. GMTV employs 200 people and is the largest wholesale car dealer in the country.

About 400 wholesalers sell around 4,000 cars every week at live auctions in southwest Dallas; GMTV makes about 25 percent of those sales. The company buys the vehicles from individuals who enter their car’s VIN and other information online. Then, Wolfe and his team transport the vehicles to the auction and prep them for sale to dealers. The company’s radio jingle reminds listeners about how easy the process is, saying, “GiveMeTheVIN.com—so easy you can do it in your underwear!”

Each week, Wolfe alternates between attending auctions in Los Angeles and Dallas. Wherever he is, his personality looms large. Between the music and the live auctioneers, the auction site in Dallas is loud—enough so that free earplugs are available as you enter the auction floor.

Several hundred bidders watch as images of vehicles pop up and bidding begins. While the auctioneer is keeping track of the rising bids, Wolfe is joking, cajoling, and threatening the bidders, who are licensed car dealers, slamming his signature piece of hose on the desk when a sale is made. The lanes are thematic, with some selling $3,000 used KIAs, while the luxury lane offers nearly new Ferrari, Rolls Royce, and Mercedes vehicles for hundreds of thousands of dollars each.

Wolfe has gained his sizable chunk of the market by being utterly committed to selling every car each day. Some sellers will have a number and not sell the vehicle if the bids aren’t high enough, but Wolfe’s strategy is always to sell the car so that more eyes are on his auctions, knowing all the vehicles will get sold and that they may get a steal. Sometimes, his commitment means he sells a car for a loss, but the increased traffic on his lanes drives prices up, and Wolfe has been rewarded for his risky strategy.

“It’s all fresh inventory that he’s buying and selling every week,” says Rich Curtis, general manager of Manheim Dallas, who has 25 years of experience in the auto auction business. “The speed that he reconditions, transports, and purchases his cars is impressive. It’s unlike anything I’ve seen before.”

Although Wolfe has more than rebuilt what he lost before his accident, he isn’t satisfied. At some point, he’d like to sell 100,000 cars a year. For now, though, he is taking things one day at a time and making the most of every opportunity, knowing the car market is cyclical and values are fluid. “Get all you can for everything, but get them all gone,” is his motto. “We are selling today’s market,” Wolfe says. “Every day is the Super Bowl.”

Get the D CEO Newsletter

Author