On its way back from the COVID-19 shock, the Texas economy was still somewhat off-kilter in the early summer of 2021. Many businesses trying to recover from the pandemic were frustrated by the difficulty of finding the labor they needed to resume full operations. An unusually high number of workers were sitting on the sidelines for a variety of reasons. Consumers were primed for a post-pandemic spending spree, but they’ve run into backlogs, shortages, and rising prices. Potential homebuyers faced an ongoing struggle to find houses for sale, with prices for what’s on the market sky-high and rising.

In short, the Texas economy is coming out of the COVID-19 crisis more sputtering than roaring.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way—not in a state that brags about its high-octane economy, dominated by the private sector and markets.

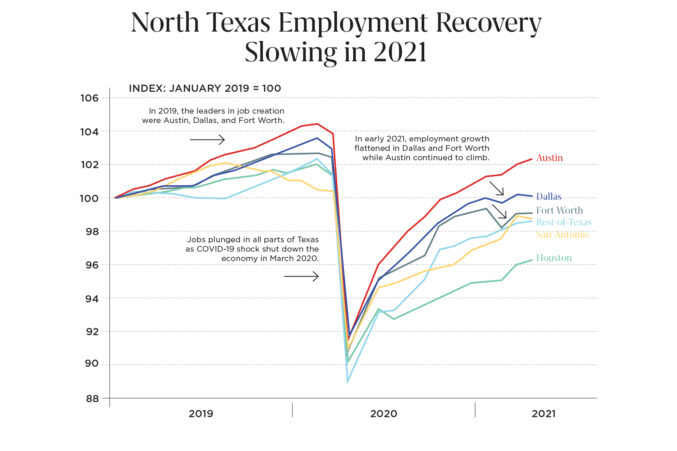

All state-imposed restrictions on economic activity ended on March 2, when Texas Gov. Greg Abbott issued an executive order lifting mask mandates and opening the state economy 100 percent. By contrast, the governors of New York and California didn’t take equivalent steps until much later. But even with its head start, Texas isn’t doing any better than the nation as a whole. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment gains since the April 2020 low point were 8.7 percent in Texas and 9.1 percent in the Dallas area—both behind the nation’s 10.8 percent.

The Texas economy typically outperforms the nation in job creation, so these are unusual times, with simultaneously high unemployment and labor shortages. The state’s recovery won’t begin to gather steam until more Texans get back to work.

The difficulty in hiring employees crimps companies’ ability to sell goods and services, forcing some businesses to cut back operations. Output can’t keep pace with rising demand, leading to shortages and bottlenecks that put upward pressures on prices.

Nothing suggests that jobs available this summer are any different from those that Texans held before the pandemic. So, why aren’t more of them being filled?

Some workers started businesses, enrolled in college, or found other jobs. Others are staying home to care for children not yet in school; if unvaccinated, they may still fear catching COVID-19. In addition, the disruptions of the past year no doubt left mismatches between workers’ skills and available jobs.

Policy can’t be ignored. To maintain household purchasing power during the pandemic, the federal government expanded eligibility for unemployment benefits and kicked in an extra $600 a week in 2020, reducing it to $300 a week this year. The money allowed some workers to put off taking jobs or become choosier in the work they’d accept. Employers have tried higher pay, bonuses, and prizes to fill vacancies—with mixed success so far.

Anecdotes and political talking points can only take us so far. What does the research say? Economists have been studying the effects of unemployment insurance on returning to work for decades. In general, they find that more generous benefits tend to extend the duration of unemployment. Duration effects are larger when few jobs are available and smaller for those with liquidity constraints—econ-speak for little money in their pockets. Waiting longer to return to work typically led to accepting worse jobs, a sign of workers settling as benefits neared or reached an end.

Previous research focused on the regular ups and downs of the business cycle, not a global pandemic. This summer may provide fresh insights into whether unemployment benefits delay the return to work.

Texas is among the 25 states, all led by Republican governors, that opted out of the federal government’s $300 a week payment in hopes of nudging more people back to work. The other 25 states, all led by Democrats, decided to continue the payments through their scheduled end in late summer. Once the data come in, this natural experiment will be fodder for economic studies on the impacts of good intentions on labor supply.

Among states, Texas stands out with a proven track record in creating jobs—for decades, it has maintained low unemployment rates while welcoming the nation’s largest influx of new residents. The pandemic didn’t change the fundamentals of the Texas economy. These two propositions make the best case for the recent labor market lull being only temporary, a short blip in the data before the Texas job-creating mojo returns.

W. Michael Cox is a professor of economics and Richard Alm is a writer-in-residence at the Bridwell Institute for Economic Freedom at SMU’s Cox School of Business.