In the last decade, Texas has become the world’s oil and gas capital, and Dallas-Fort Worth is the place where energy deals get done. With producers and pipes-and-refineries companies shifting operations to Houston, North Texas’ experience with the money side of the industry has fostered the growth of private equity firms that fund both startups and megadeals alike.

“As the industry gets more capital intensive and less labor-driven, Dallas is increasingly where checks are written to help my client companies add both to their management teams and the technology they need to grow faster,” says Bryce Erickson, a Dallas-based senior vice president at the valuation firm Mercer Capital.

But while West Texas’ Permian Basin is one of the biggest oil and gas plays ever, mid-tier crude prices mean change is coming starting this fall both for businesses that work there and the local financiers who back them. As of this summer, oil was trading in the $50 to $70 range in which it has been stuck since November 2016. “Expectations are that the commodity prices that drive industry activity will not change significantly” in the near term, said Shishir Khetan, a Houston-based managing director in the valuation advisory group of Stout.

Still, smaller oil and gas producers may find themselves in technical default on debt because of their banks’ twice-a-year revaluation of their proved reserves based on what those lenders believe future oil and gas prices will look like, experts say. “Of the restructurings happening in oil and gas, we will have more weighted on the exploration and production side,” says Drew Lockard, a Dallas-based managing director at Stretto, a consultancy for companies in distress.

E&P businesses thus may see a round of mergers and acquisitions, as might the firms that help them find raw fuels in the ground and get them to the surface.“Of the 95 publicly-traded oilfield services companies, the vast majority have market [values] so small that institutional investors won’t touch them,” says Bruce Bullock, director of the Maguire Energy Institute at SMU. “To help E&P companies grow, that segment must cut costs, which is easier if they consolidate.”

A New Way To Look At Producers

Of course, problems in oilfield services are a chance for someone else to make hay. “We see the most opportunity of potential distress to add onto our existing investments and grow market share during any downturn,” says Chase Paxton, director of finance and valuations at Irving’s NGP Energy Capital Management, which manages $12.4 billion in assets.

An issue facing production companies in particular is that investors increasingly value them by the same measuring sticks they use for other industries, such as the ability to generate free cash flow, Paxton says. Free cash flow is money businesses generate after paying for operations and maintaining their large properties. “I believe that many E&Ps can generate cash and deliver the return on capital that investors are looking for,” said Paul Moorman, a Dallas-based managing director at Stephens, a large investment bank.

But that requires them to change how they do things, such as by consolidating their properties to build areas of expertise and running their businesses for the long term, he adds. “It’s not sufficient for them to say, ‘I am going to drill a few wells and flip it to a larger operator.” Late this past summer, though, prices for E&P-related properties and companies were high enough to dissuade buying in that segment. “There are more reluctant sellers, so there’s large difference between the bid and the ask,” says Ryan Bartholomee, chief financial officer of Midland’s Shenandoah Petroleum. “We’re focused on the leases we do have and getting those developed.”

Aside from private equity, companies that need capital may look to wealthy families in DFW who invest privately in oil, gas, and renewable businesses. In the Dallas office of Tiedmann Advisors, which helps clients with money management, senior vice president Kyle Manley says the firm is positioning four to eight percent of some portfolios in “midstream” businesses, which handle pipes and refineries. “We’ve been early investors in a number of firms with great success over the years,” he said. “In Texas, most families own some exposure to energy.”

Pipeline constraints in the Permian means crude oil priced in Midland last year cost anywhere from 37 cents to $15 less than crude priced in Oklahoma, according to Ed Longanecker, president of the Austin-based Texas Independent Producers & Royalty Owners Association.

“This directly impacted the bottom line for operators, particularly smaller producers that have a higher breakeven point or less contracted takeaway capacity,” he says. Though industry is moving to add pipelines, “the bottleneck may not be fully resolved until late 2019, assuming infrastructure projects and production stay on track.”

“Utterly, Fantastically Wrong”

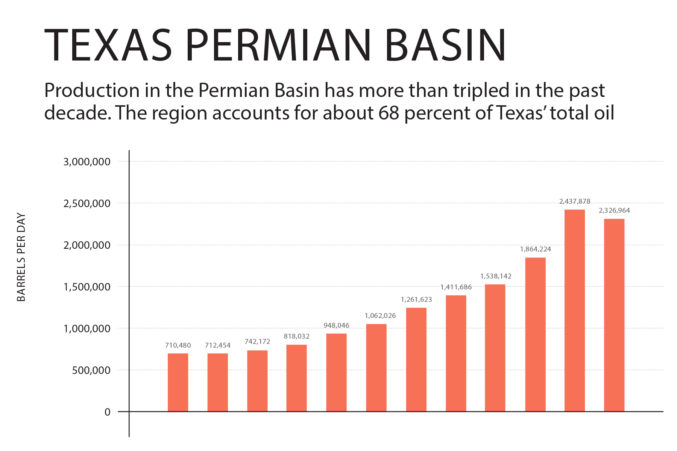

DFW’s role in energy finance now matters because of technology advances in the last 10 years that make it economical to extract raw hydrocarbons encased in sedimentary rock. “Up until this point in 2008 and 2009, crude production in Texas had done nothing but decline since the early 1970s. Conventional wisdom held this would continue, and nothing could be done to change this,” says Karr Ingham, Amarillo-based consulting petroleum economist to the Texas Alliance of Energy Producers.”

What changed was a series of small improvements to hydraulic fracturing—or blasting underground rock open with high-pressure liquids—and horizontal drilling, or cutting holes sideways or upward in the ground. Suddenly, drillers had affordable ways to draw crude oil and gas out of soft rock called shale. “Everybody turned out to be utterly, fantastically wrong,” Ingham says. “What we’ve done is quadrupled oil production in the last 10 to 11 years, more than doubled U.S. production, and become the most important producer on the planet at this point.”

Even with those gains, the formation may be richer still in underground fuels. “The Permian Basin is the most prolific shale formation in the world,” Longanecker says. “Oil production there could grow by over 50 percent by the year 2023. The federal Energy Information Administration forecasts that Permian shale oil in Texas alone will account for more than 50 percent of all new global production of that commodity over the next five years.”

As the scope became apparent of Texas’ new opportunity in energy, DFW was poised to move fast, given the expertise here in oil and gas finance. Some of it may be a legacy of the 1980s, when the state’s banks were major lenders to the industry, according to Bernard Weinstein, economist and associate director of SMU’s Maguire Energy Institute. “Most of the big banks were based in Dallas-Fort Worth.”

The finance roots extend 50-plus years, when local families like the Hunts, Murchisons and Richardsons agreed to let banks lend money to energy ventures they had backed based on reserves in the ground, according to Erickson of Mercer Capital. “They were pioneers.”

Suppliers Grow, Too

DFW wouldn’t be an energy finance hub if not for its plethora of related vendors that handle key tasks on deals. The new work coming from places like the Permian has heated up an already tight talent market in our region (See “Hotbed for High Finance,” below.)

The result: Local companies are having to adapt. “The big firms have 80 hour work weeks. Ours are about average, sometimes a little higher or lower,” says John Vallance, who leads the Fort Worth energy industry group at Whitley Penn, a North Texas accountancy. The busy finance market has also helped build related energy-related businesses. “When we started in 1993, we had 70 exhibitors and 700 attendees,” says Le’Ann Callihan, director of NAPE Expo, which puts on events for trading of energy-related land. “This summer we had more than 1,200 exhibitors and 12,500 attendees at our annual summit.”

And with private equity having invested in small and mid-sized energy companies, lenders are reaping the benefits of the discipline that professional investors bring to their portfolio companies. “The level of talent on the financial side of energy is incredible,” says Bill Schonacher, president and CEO of International Bank of Commerce-Oklahoma. “That makes our jobs easier, as being creative in problem solving is a talent that the energy industry has,” adds Schonacher, whose organization is part of Laredo-based IBC Bank.

Texas’ humming oil and gas market is fueling efforts to build something similar in Mexico. The country’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, wants to grow its industry from 3 percent to 4 percent of the economy, where it is now, to six percent, according to Raúl Cedeño Casillas, editor of Petróleo & Energia, a leading business magazine in Mexico. “It’s an ambitious goal,” he says, adding that the administration is trying to build foreign participation partly by eradicating corruption.

“It’s no secret that relations with the United States have been rocky,” Casillas says. “They’re looking for investment. It’s just that the parameters of the opportunity are being revised so they can move forward.”

Petróleo got its start amid efforts to add transparency to Mexico’s state-owned oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos, or Pemex, according to Javier Senderos Lopez, a director who helps run the publication’s business side. “We saw a lot of suppliers to Pemex that were under the radar and needed promotion,” he says.

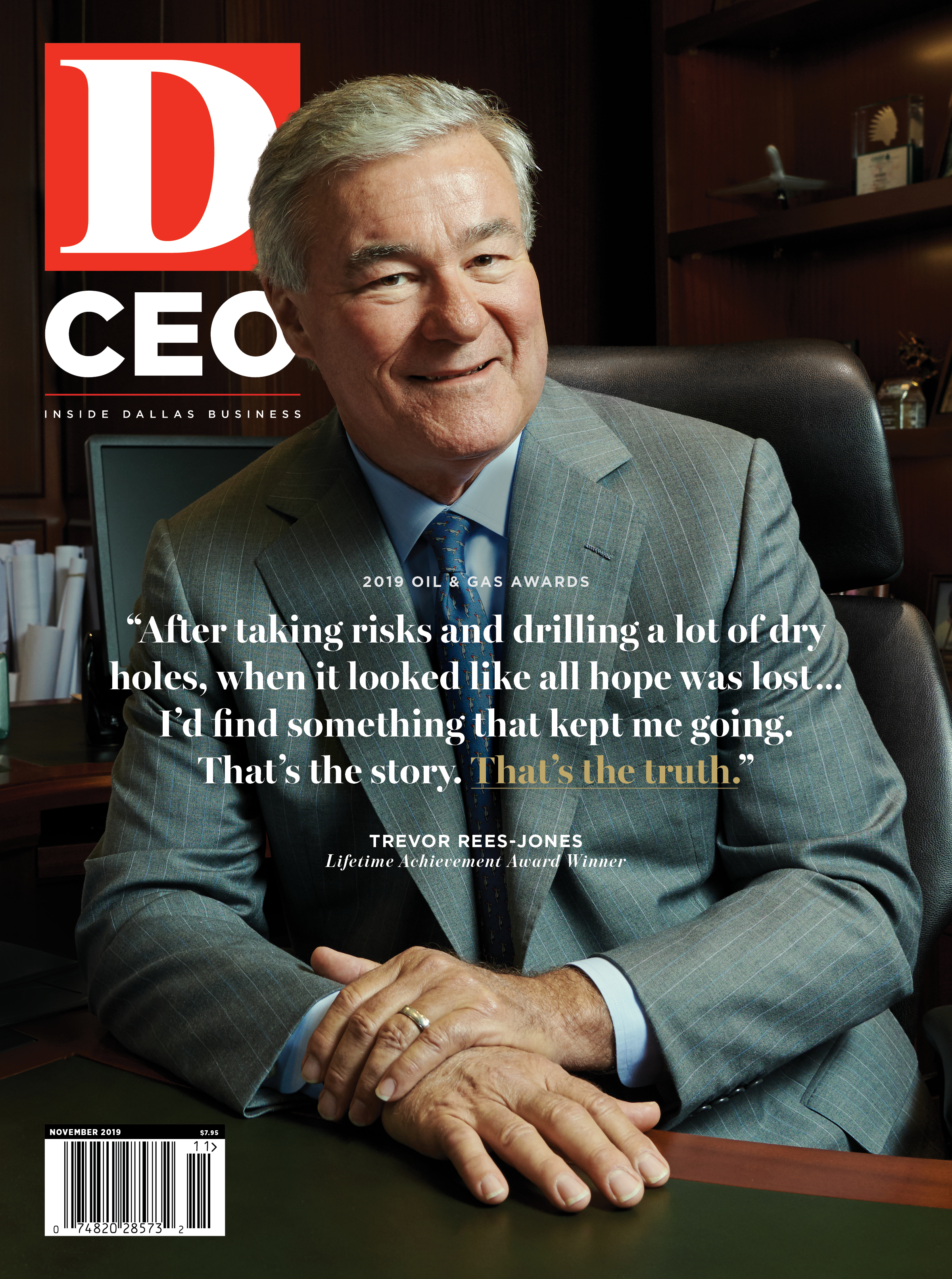

See the winners of D CEO’s 2019 Oil & Gas Awards here.

Hotbed for High Finance

From SMU to TCU, area universities are preparing sought-after investment banking students with practical training and access to dealmakers.

Before Texas became an energy epicenter, the state’s schools were improving the finance and business educations that now make graduates hot commodities in the industry. In Dallas, SMU launched an alternative assets management program, in which 50 undergrads learn about investment banking by building financial models and PowerPoint presentations based on case studies.

Through what students call “alts” give them windows into more industries than oil, gas, and renewables. The modeling work is ideal for undergrads like Arthur Yuen, who is interested in the exploration and production side of energy. “In my opinion, it’s the most prestigious program on campus,” says Yuen, a competitive swimmer who, like all participants, went through roughly three weeks of mock interviews to get a spot in it. “Every student is pushed to do the best we can.”

In Fort Worth, TCU offers a 10-month graduate certificate for people working in energy, along with an undergraduate minor in the field. In addition to individualized study projects, students work with others on a capstone effort and have mentors, according to Ed Ireland, director of the TCU Energy Institute and the Ralph Lowe Energy Management Program. Mary Ralph Lowe, who endowed the program in the name of her wildcatter father, wanted “to eliminate or significantly reduce on the job training,” Ireland says.

Texas A&M offers a student-run program, Horizons, that connected finance and business major Mark Lutz with mentors working in investment banking. “I learned from them about the exciting but demanding workflow they saw daily advising companies on significant decisions,” says Lutz, now an associate at Dallas’ Tailwater Capital.

Anton Cordes, a finance student who is helping run the program this year, used an internship to land a job upon graduation next year as an investment banking analyst in Barclays Capital’s global natural resources group in Houston. “While New York can be a great place to start a career, I decided I did not want to build a life there,” he says. “Texas is where my family and friends are.”

Companies in need of energy finance help will be looking to hire people like A&M business major Mason Fugger, also a Horizons director who will graduate next year. “I want a financial analyst role in which I develop my career on an accelerated pace compared to normal corporate positions,” he says.