To create tempered steel, an alloy of iron and carbon is subjected to a series of compressions using extremely high pressures and heat. It’s an ancient technique that dates back to Galilee, 1,200 years before the birth of Christ. Over and over again, the steel is pounded and folded, formed and reformed, and put back into the fire. But rather than weakening the steel, it strengthens it, and creates one of the hardest, toughest materials on earth.

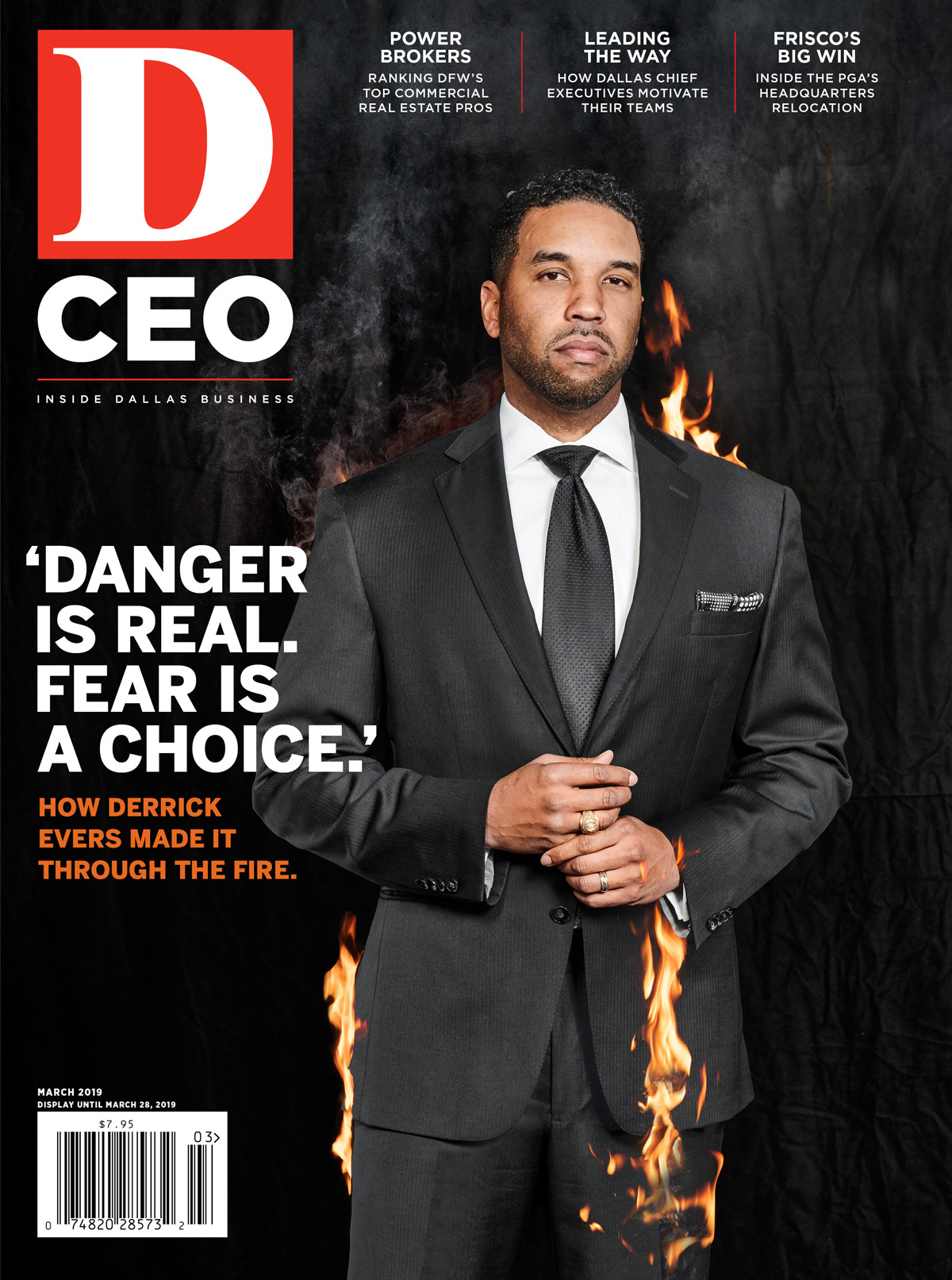

Derrick Evers, 41, likens the process to what he and his business partners endured after the downfall of Neal Richards Group, a company they helped build. “I feel like we’ve gone through this fire to make us stronger, both in our business and our faith,” Evers says. “Without this experience, we may not have been humbled in the same way.”

Evers, Nick Summerville, and Lee White formed Kaizen Development Partners in May 2015, a few days after they were ousted at Neal Richards Group. NRG was launched in 2008 by Drs. Wade Barker, a bariatric surgeon, and Richard Toussaint, an anesthesiologist, to develop physician-owned and operated hospitals. They persuaded two other doctors to come on board as partners, and lured Evers away from The Staubach Co. to serve as CEO. Summerville joined a few months later, and White in 2012.

Within about seven years, NRG built more than $1 billion in assets, mostly luxury hospitals under the Forest Park brand in Dallas, Fort Worth, Frisco, Southlake, Austin, and San Antonio. Modeled after the Ritz-Carlton in look and service, the facilities earned accolades from patients and cities and attracted hundreds of doctor investors.

“For a long time, it was a special place for all of us,” Evers says. “We were part of something transformational. We interacted with more than 700 physicians during the course of those seven years. And with the exception of a small handful of individuals, the overwhelming majority of those men and women were amazing.”

The timing wasn’t ideal. A recession was getting underway and funding for new projects began drying up. But demand was strong, so the doctors formed and controlled affiliate companies to handle financing and brokerage.

Buoyed by success, Evers and his team at NRG expanded the concept to support hospital-anchored mixed-use campuses, and plans for ongoing expansion continued. But by 2015, things were clearly unraveling on the hospital operations side. Toussaint, who had been removed as a manager of NRG a year earlier, was indicted for healthcare fraud. The Forest Park hospital chain was in disarray, according to numerous D CEO reports, and began missing rent payments to NRG.

Barker—who would later join Toussaint in pleading guilty in a multimillion-dollar, patient-referral kickback scheme—moved to assert control over everything and fired the NRG execs. They didn’t see it coming. “It felt like a punch in the gut,” Evers says. “We didn’t know why someone would do this to us. We felt like we had birthed a business; we poured ourselves into it. And just like that, it was over.”

Motor City Mayhem

In its heyday, Detroit was a bustling metro and the automotive capital of the world. But by the 1980s, it had become a haven for drugs and violent crime. Evers grew up in the inner city. The stress of his surroundings and the very real danger “played with my mind all the time,” he says. He had his shoes stolen off his feet, his jacket stolen off his back, and his bike stolen out from under him. “I remember always being scared … always,” he says. “It was an environment filled with lions and sheep.”

Sports, faith, and strong parents were his salvation. From an early age, Evers was obsessed with drawing buildings, including some that housed a business he intended to run someday. “I’m going to have my own company,” he’d tell his mom. “You can speak things into reality,” she’d say. “All you have to do is claim it.”

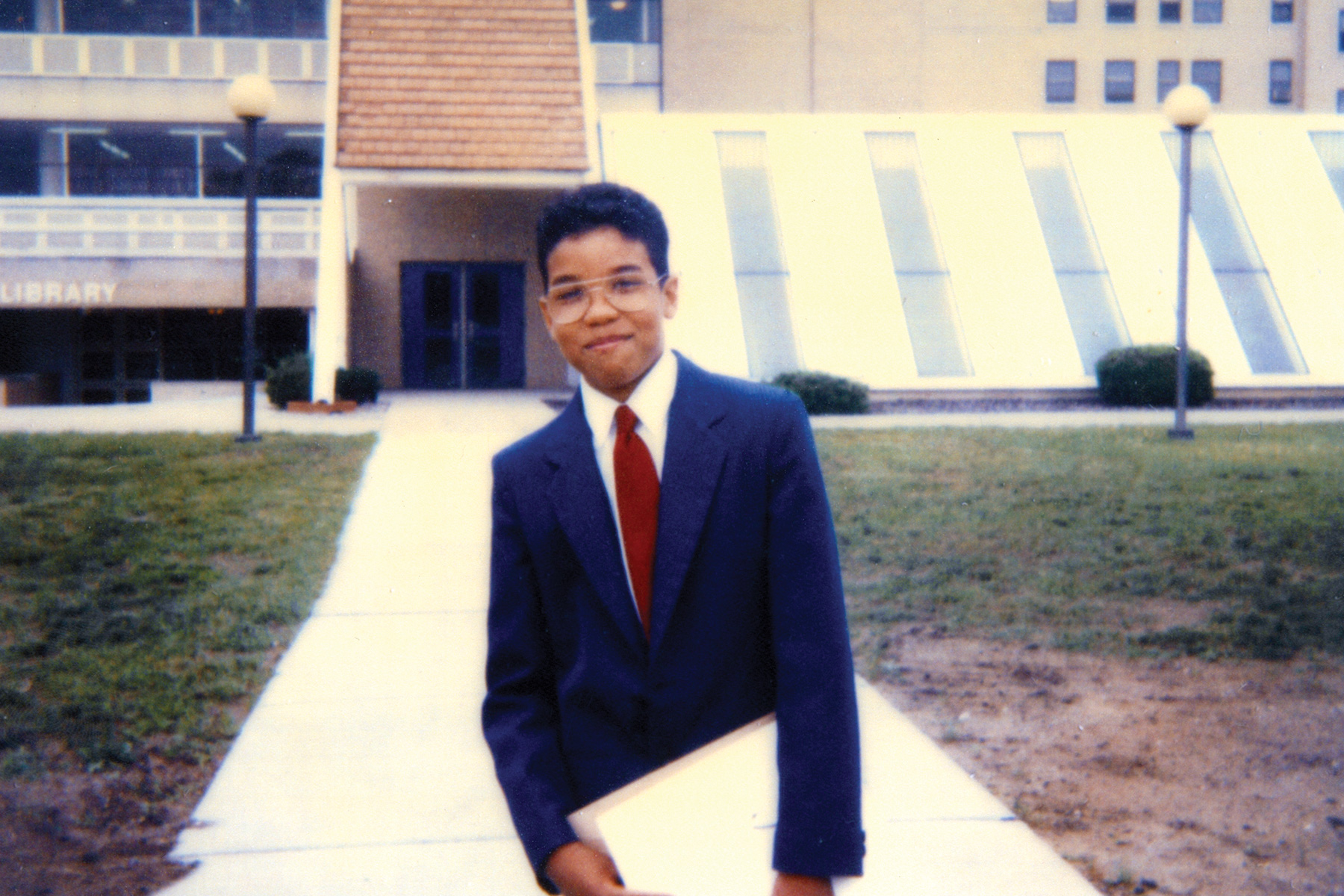

Evers wanted to feel smarter, so he talked his mom into getting him some glasses. He’d put on a suit and tie, wear the glasses, and pretend he was a CEO. Determined to stoke the fire, his mother enrolled Evers in an architecture camp at a nearby university, where he’d get lost in thoughts of building a better world.

He attended Cass Tech, one of the few magnet high schools in downtown Detroit, taking a 45-minute bus trip to get there. One day during his freshman year, he and a buddy were walking down a street when a car pulled up—and a gun came out.

“If you run, I’m going to shoot both of you,” the gunman said. He waved the pistol back and forth, saying, “Now, which one of you is it going to be?” The gunman pointed his weapon at Evers, who stood frozen in fear, certain he was going to die. Then, suddenly, he changed his aim and pulled the trigger. Evers’ friend fell to the ground.

The friend survived, but Evers’ parents decided enough was enough. Determined to get as far away from Detroit as possible, they quit their jobs, packed up their son and three daughters, and moved in with Evers’ uncle and aunt in Fort Worth. It was August 1992, and with triple-digit temperatures, “it felt like we had moved straight to hell,” Evers says. But for the first time in his life, he felt safe.

Breaking Down Barriers

Evers’ parents found a home in Bedford, and he finished high school at Euless Trinity, where he was a point guard for the school’s basketball team. He also played ball at Texas A&M University, a school he had dreamed of attending ever since he was a young boy. But it wasn’t sports that inspired his love for the school; it was the construction science program in its College of Architecture. “I was the only African-American in my classes, but I didn’t care,” Evers says. “I was where I felt I belonged.”

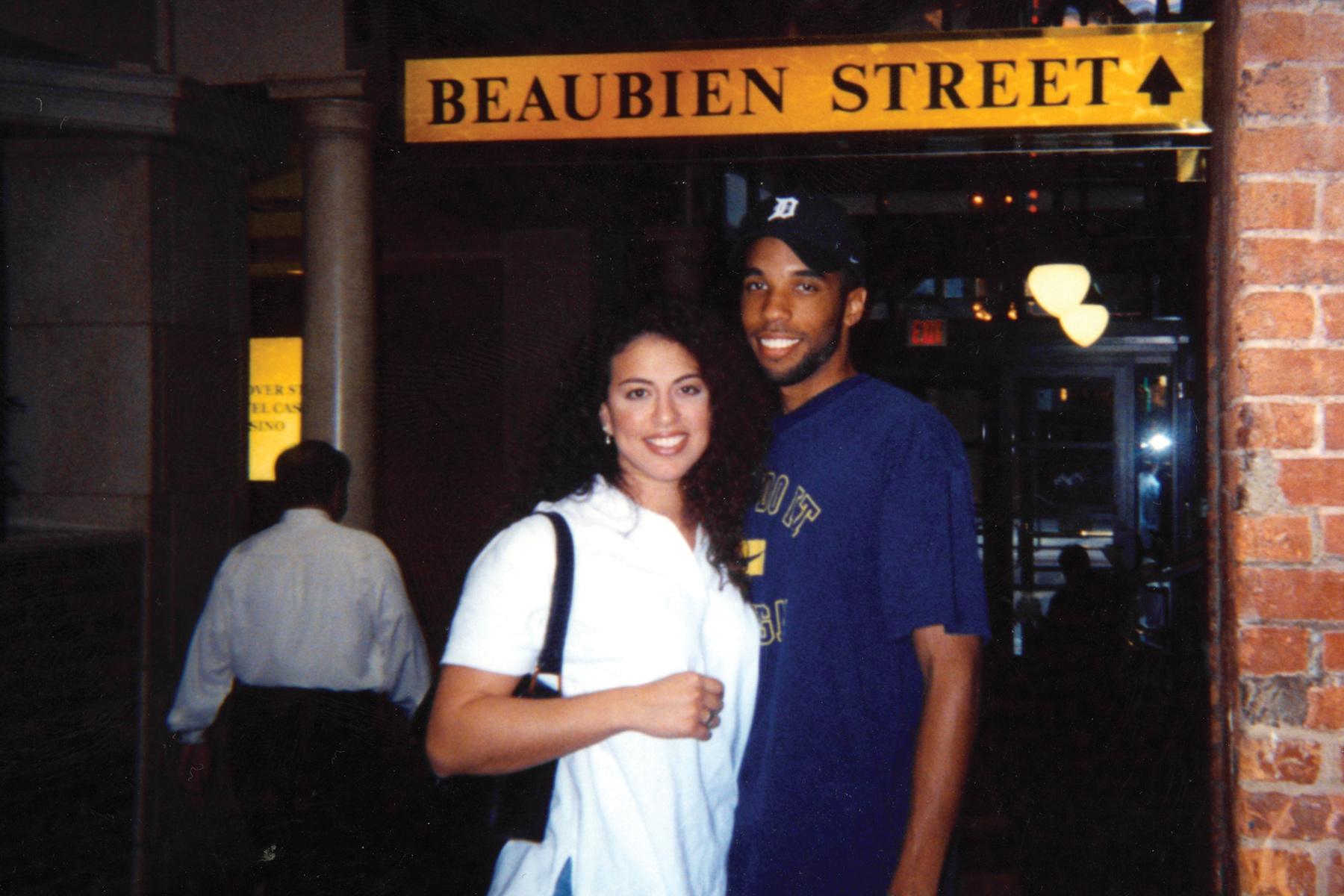

He quit basketball to focus on his studies and free up time to earn money for school. He met his now-wife, Monica, his sophomore year, and was smitten from the start. Too shy to ask her out, he’d wait by the mailboxes on the south side of campus, just to get a glimpse of her when she stopped to pick up her mail. Then, one night while hanging out in the commons with friends, Monica came in. They ended up playing pool and talking, and at the end of the evening, exchanged phone numbers. For three days, Evers tried to work up the courage to call. Finally, Monica took matters into her own hands and called him. They were married six years later.

After school, Evers joined Whiting-Turner Contracting Co. in Dallas. A few years later, he moved to Trammell Crow Co., so he could learn about development. Before long, he was recruited away to The Staubach Co. by the former Dallas Cowboys quarterback himself. Evers focused on office, industrial, and healthcare projects, including initial plans for a hospital “built around the physician chassis” for Barker and Toussaint.

The doctors clicked with Evers. They told him of their plans to form a development company that focused on healthcare real estate, and asked the then 30-year-old to serve as CEO. Neal Richards Group opened in August 2008. A year later, Forest Park Medical Center was up and running in Dallas. Within six weeks, it was operating at capacity.

Signs of Trouble

Summerville and Evers were classmates at A&M, and both wound up working for Whiting-Turner. After he took the helm of Neal Richards Group and was building his team, Evers decided to reach out to Summerville, who had taken a job in Las Vegas a few years prior. But Summerville beat him to the punch. “This is so eerie,” Evers said when he answered the call. The Las Vegas construction market was in a downward spiral, and Summerville, 40, was ready to come back to Texas. Like Evers, he wanted to be part of the bigger picture and get into development. It was a perfect fit. Summerville took on a chief operating officer role at NRG and grew with the company.

“We had a clear and clean conscience, and as the story played out, it has been reconciled. Everyone wants to be exonerated immediately; time has a way of setting the record straight.”

Nick Summerville

White, 43, was raised in southern Louisiana. After earning an accounting degree at UL-Lafayette and a law degree from LSU, he decided to seek his fortune in Dallas. About 10 years into his career at Jackson Walker, White began doing work for NRG. Within a few months, Evers asked him to come on board as the company’s in-house counsel. The two met at Breadwinners on McKinney to discuss the possibility. “I’m an attorney, so I’m naturally risk-averse,” White says. “But I’m also a sappy sports fan who’s not afraid to admit that I still get choked up watching the movie, Rudy. Derrick is a master at reading people and has an innate ability to connect. So, he wraps up our conversation by telling me a story from his basketball days at A&M.”

Here’s the story, from Evers: “There were just a few seconds left in the game, and we were down by 1. I had the ball, but I was too scared to take a shot. I don’t remember if we won or lost. I only remember that I passed the ball because I was too afraid to shoot. It haunted me, and I decided I was never going to make that mistake again.”

The story had its desired effect, and White joined NRG in December 2012. There was a mountain of things to do but also loads of untapped potential. Still active on the development front, NRG began to monetize its existing assets, selling and refinancing to fund new projects. By all accounts, 2013 was a banner year, and 2014 started out strong. But signs of trouble began to appear. Forest Park was struggling as a system and falling behind on rents payments to NRG, even as it continued pushing new deals.

A year later, the situation had become untenable. Evers was in Boston, attending an OPM (owner/president management) program at Harvard Business School, when he and the other execs got word that their time at Neal Richards Group had come to an end.

Hitting the Restart Button

Fired on a Friday, the men took the weekend to clear their heads. On Monday, they gathered at Summerville’s home to talk. They hadn’t planned to leave NRG, so they had no exit strategy, and no plan B. They were still dealing with the shock and emotion of it all. They knew they had a strong foundation of trust and respect, they loved the development business, and they liked the autonomy of being in charge. Perhaps they could learn from the past and battle their way back to the top.

The partners thought they would be shielded from the Forest Park chaos, as their development arm was separate from operations. But few on the outside made the distinction, and the men soon found themselves treated as pariahs. Business associates stopped calling. No one wanted to be touched by the scandal at Forest Park. But a few friends stood fast. Among them was Jim Williams, founder and chairman of LandPlan Development Corp. He had gotten to know Evers in 2012 as investor in a Forest Park hospital in Southlake. Although they were decades apart in age, they found they shared similar spiritual and business values and became close friends.

“I knew Derrick was getting on a tightrope in that situation, and I saw an opportunity to help,” Williams says. “[NRG] crushed him. I’ve been crushed before, and I’ve been broke twice. I’ve seen guys who can’t come back from that, and who would have a hard heart for a long time. Derrick held his head high and kept walking.”

When Williams heard about the plans for Kaizen Development, he offered to seed the company. Evers broke down and cried. It wasn’t just the generosity from his friend that meant so much to him; it was Williams’ belief and confidence and trust.

Another loyal advocate was Don Powell, principal at BOKA Powell, which had designed the Forest Park hospitals. Powell knew the city of Allen was looking for a partner on an office park it was hoping to get off the ground. He approached Dan Bowman, CEO of the Allen Economic Development Corp., and recommended the Kaizen team.

Bowman was having a tough time convincing developers of the viability of Class A office space in Allen. But the idea made complete sense to Evers, Summerville, and White, especially because the 17-acre site the AEDC controlled sat just across the street from Watters Creek, which would provide an ideal amenity base for office tenants.

Talks began in 2016. After several long months, Kaizen was selected as the project’s developer. “They were relentless in finding the right capital partners and putting a deal together that matched the vision of what the city wanted,” Bowman says.

With AEDC’s support and investors in hand (including a Belgian classmate of Evers from the OPM program at Harvard, who stepped up with seven figures), Kaizen broke ground on One Bethany East in early 2017, nearly two years after the launch of their firm. Around the same time, the Kaizen team was in a fierce battle for a build-to-suit for NetScout. When they were told they had lost out on the deal, the partners refused to accept it. “When you absolutely have to win, you’d be amazed at what you can do,” Evers says.

The partners came back with a revamped proposal and made the save. NetScout took occupancy of its new 145,000-square-foot headquarters in August 2018, and Allen had the start of an honest-to-goodness, Class A office park.

One Bethany East is now more than 80 percent leased, with Credit Union of Texas as an anchor tenant. In April, Kaizen will break ground on One Bethany West, an eight-story, 200,000-square-foot spec building that will be the tallest office tower in Allen. Two remaining sites can accommodate up to 750,000 square feet of future office development.

Band of Brothers

With projects in Allen well underway, the Kaizen partners began looking for their next big play. Throughout 2018, they quietly pursued a coveted piece of property in Uptown, a triangular tract bounded by Cedar Springs Road and Akard and Ashland streets. All of the “blueblood” firms in Dallas had been trying to get their hands on it, as it’s one of the last remaining developable sites in the neighborhood. The market was stunned in October when Kaizen won out.

The partners say their story resonated with the seller, Mike Karns, founder and CEO of Firebird Restaurants. “It wasn’t one of those things where the highest number was going to do it,” Evers says. “We wanted to create something unique, a sense of place that would connect Uptown to Victory. We wanted to connect people and neighborhoods. What also resonated with him is that we’re not unlike him. We’re the underdogs.”

Designed by BOKA Powell and called The Link at Uptown, the 300,000-square-foot tower will include a fitness center, two restaurants, conference lounge, golf simulators, balconies, outdoor terrace and garden space, and generous parking. The plan is to demolish a vacant buiding that occupies the site this summer and finish in late 2021. “What we’re really excited about is being able to contribute to the Dallas skyline,” Evers says.

Three-and-a-half years into their venture, the band of brothers at Kaizen are well past finding their rhythm. All are partners in the company; their different leadership roles play to their strengths. Summerville serves in a chief operating officer capacity and is described as the “soul” of the company; White has evolved from a deal-making attorney to a developer with a legal background who finds a way to get deals done; and Evers is the big-vision guy and the face of the company.

The partners say they are at peace with the past. “There wasn’t anything in our closet from NRG that we were afraid of,” Summerville says. “We had a clear and clean conscience, and as the story played out, it has been reconciled. Everyone wants to be exonerated immediately; time has a way of setting the record straight.”

Although they’ve been through hell, Evers, Summerville, and White are in a great place now, and the phone is once again ringing off the hook. The partners hope others can learn from their experiences. “In this age of Facebook, all you get are the highlights,” Evers says. “Everyone wants to talk about the great times, but no one wants to talk about the tough times.

“Our journey has been one of failure, it has been one of embarrassment, and it has been one of fear,” he says. “But on the flip side, it has been transformational, empowering, and inspiring. We are not promised a road without tests, but we are ready for them, and our faith tells us that we will be victorious … together.”

New Philosophies

Derrick Evers says he and his partners learned a lot from their “rise, fall, and rebirth” experience. Here, he shares some strategies they now use at Kaizen Development Partners:

Understand danger and fear.

“It’s important to know the difference. Danger is real. Fear is a choice. If you can decide to be fearless, there are no limitations on what you can do.”

Have strong opinions, loosely held.

“We want our people to express their opinions, and we want to be challenged. But we want those opinions to be loosely held. So, if new information comes, they are able to pivot accordingly.”

Develop a personal balance sheet.

“A financial balance sheet is the least important. Learn to have the proper balance of trust, work ethic, perseverance, and humility.”

Identify wins.

“Sometimes you have to understand that there are things you can do right now, and other things you can maneuver around.”

Get to the wii.

“In any company, there are ‘we’ folks and ‘I’ folks. ‘We’ folks grow your organization; ‘I’ folks are your stars. To succeed in business, you need both. The trick is going from ‘we’ and ‘I’ to spell it ‘wii.’ We’ve paid a lot of attention to creating that blend.”

Remove emotions from decisions.

“Problems don’t have emotions; people do. Creative solutions can be found when you tackle problems together. Listening to one another, being more inclusive, and taking the emotion out of things is how you grow.”

Focus on making impact, versus impressions.

“This mindset can be liberating and unshackle you from difficult situations.”

Kaizen.

“The word ‘kaizen’ is Japanese for improvement. It’s the name of our company because continual, incremental improvement, personally and as a business, is what we strive for every day.”

Keep it simple.

“This is the foundation of our success. It’s knowing what we do well, communicating effectively, and executing with excellence.”