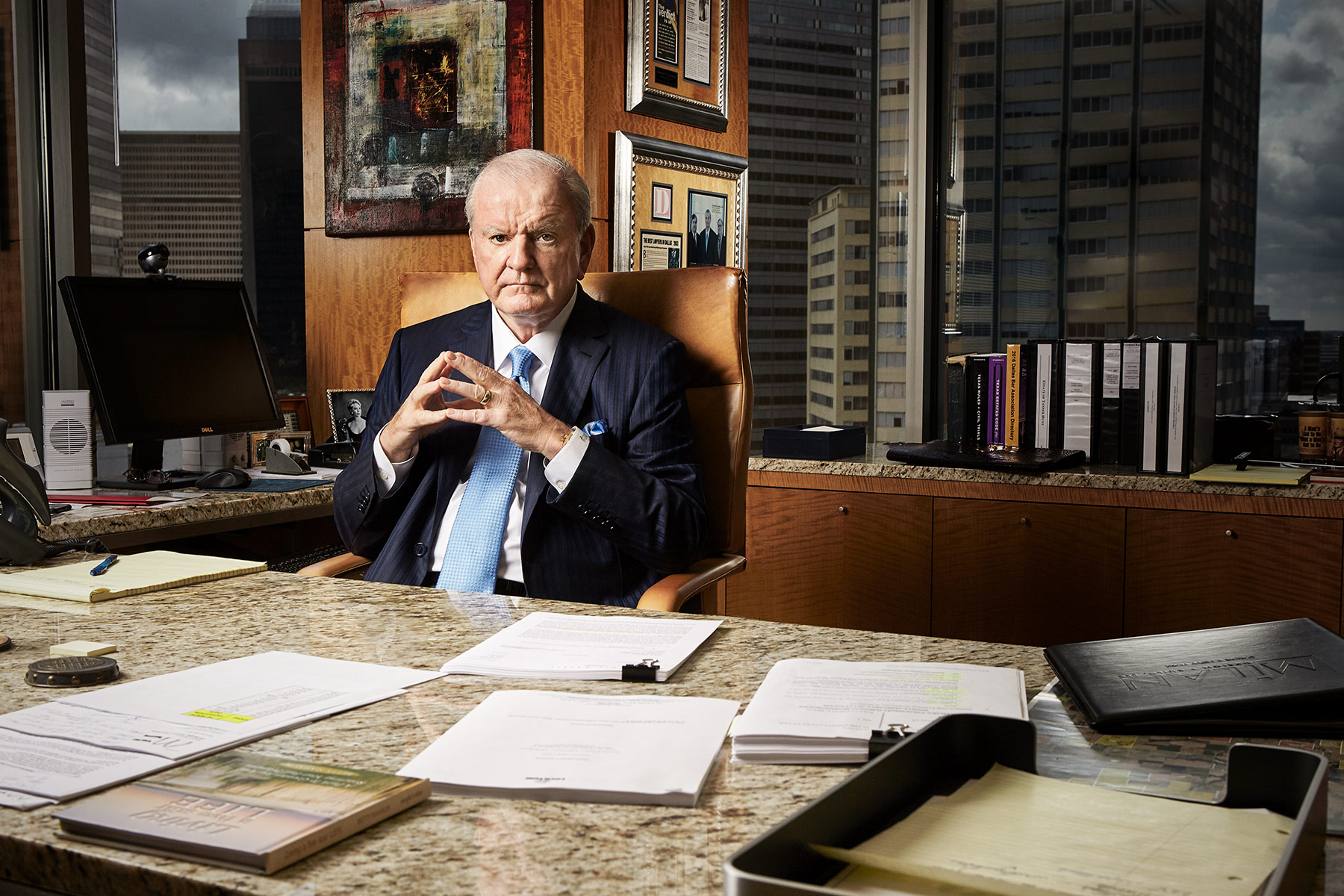

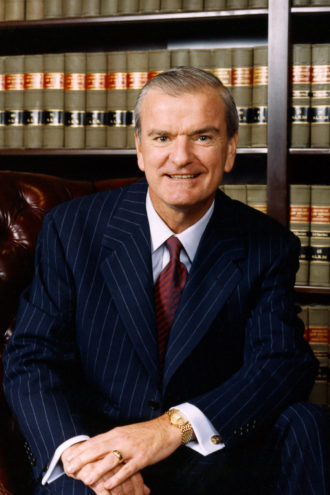

I’ve been practicing law for more than 40 years, and I’ve loved every minute of it. I’ve had many challenges in my career over the years, so the fact that I’m still here suggests something: maybe I’ve got good genes! My dad had a 10th grade education. He’d been raised on his family’s tobacco and cotton farm in North Carolina, then left the farm and married my mother when he was 19 and she was 16. He became an auto mechanic and, later, a used-car salesman for a Pontiac dealership in Jacksonville, N.C. We left there when I was about 8 years old and moved to Wilmington, N.C. My dad went from the Pontiac dealership in Jacksonville to auto sales at a much larger dealership in Wilmington that had Pontiac, Buick, Mercedes-Benz, GMC, and Volkswagen, and he eventually became the sales manager.

My mom, who had graduated from high school, was a homemaker. She would take in ironing from people in town and clean houses to help subsidize my dad’s income. They used to talk to us all the time about the importance of education. “While we can’t pay for it,” they’d say, “study hard, try to get a scholarship, go to school.”

My dad would come home at night from working all day in car sales. He was well-thought of, well-respected. After dinner—we called it supper back then—he’d go into a hallway and grab a chair. He’d take out his little Rolodex that he carried in his pocket in a tablet form, and he’d pick up the phone. He’d dial the rotary phone and call people, trying to encourage them to stop by the dealership and see if they might be interested in buying a new car. I would sit there and listen to him and watch him.

I learned so much from my dad about how to treat people with respect and dignity.

I learned so much from him about how to treat people with respect and dignity, and how to talk to people. Wilmington was a big seaport, so there were a lot of dock workers there. They made good money, and my dad became friends with many of them. He would sell them cars, and they loved my dad. What he taught me is that, regardless of where you come from, what little you start with, if you work hard, if you’ve got the right value system, if you treat people with respect, and you’re honest in your dealings with others, you’re going to succeed and do well if you have it in you.

But Wilmington was a town where, it seemed to me, the ones who really got ahead were the ones born into money, or their families were doctors or lawyers or professionals—or they married into it. So, the people that didn’t come from the side of town where you had those options, most of them moved elsewhere. I wound up doing that, too. It’s not because I didn’t like the town, it’s just that I never thought I would have opportunities to do what I dreamed of one day doing by living there. I wasn’t in a family that could provide it.

After getting a full scholarship and graduating as an accounting major, with honors, from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, in 1969 I went over to Memphis, Tenn., where I attended graduate school at what was known then as Memphis State University (later called the University of Memphis) to get a master’s degree in accounting. I thought I was going to be a CPA the rest of my life, until, in my last semester, the dean of the business school suggested I go to law school. He said, “You know, Don, you’re really good at tax. So you ought to consider being a tax lawyer.”

I told him that I couldn’t go to law school without a full scholarship. My family didn’t have the resources to send us to school, and I’d gone to Memphis State on a full scholarship. He said, “Well, maybe I can help you with that.” He introduced me to a prominent lawyer in Memphis, John Kimbrough, who was on the law school’s board of trustees at Southern Methodist University. They brought me down here for an interview, and I did well on the LSAT, and [Kimbrough] recommended me for a scholarship. As a result, I got a scholarship to the SMU law school for three years.

From Taxes to Trials

From the first day I was in law school until I finished, I loved it. I loved the debate side of it, articulating the points of view and hearing the other side and trying to out-debate them, if you will, in class. I graduated from the SMU law school in 1973 and went to work for a Dallas firm known as Lyne Klein French & Womble, starting out as a tax lawyer. About nine months into the practice, which I really enjoyed, one of the senior partners brought me into a case in which he was representing a group of doctors. It was a federal tax case, and he used me as a research tool to give him information that he could use. I went to court with him every day.

After we got through that trial, the senior partner, Dawson French, said, “Don, you really are good at this. Preparing the witnesses you were spot on, and you seem to have a knack for dealing with people and what questions should be asked, or what questions I might ought to ask.” I hadn’t asked a single question in the trial myself, but I sat right next to Mr. French and gave him all the questions he should be asking and the places where I thought he ought to object and do a cross-examination.

So, he called me in with the managing partner, a gentleman named Fritz Lyne—a legendary trial and labor lawyer—and said, “Fritz, you know, Don is really good at doing the tax work, but we have a young trial lawyer here in the making. We need to let him do some cases.” And Fritz said, “Well, Don, how do you feel about that”’ I said, “Well, I’m fine with it. I prepared to be a tax lawyer. Even before undergraduate school, I thought I was going to be an accountant and run a Winn-Dixie store. That all changed when I went to law school. So, now I’ve prepared to be a tax lawyer, but if you want me to try cases, I’ll be happy to do it. Tell me what I need to do, because I’ve never done it.”

Juries don’t want to see a boring lawsuit. They want to see theater and be entertained.

Mr. French said, “He knows what to do, Fritz. We just need to let him go around with some of these trial lawyers on a few cases, let him see how they pick a jury and how they do this and how they do that in the courtroom. Let’s give Don a chance. He ought to be doing something other than writing wills and drafting corporate documents.”

Pretty soon, they started giving me little collection suits—$2,000 to $5,000, say—for a big meatpacking plant in downtown Dallas. They were selling meat and whatever to a lot of vendors and grocery stores and smaller people that couldn’t or wouldn’t pay. So I was hired to file all these lawsuits and, in about a month, I’d get like 20 cases on my docket. Within the first six months of starting out as a trial lawyer, I tried and won several cases to jury verdict, and I was loving it. From that point on, to this day, I’ve never done anything but trial work.

I stayed with Lyne Klein from 1973 until 1977 and then, in ’77, I joined a 100-year-old firm called Seay, Gwinn, Crawford, Mebus and Blakeney as an associate. A year later, they made me a partner at age 30—one of the youngest partners ever. My income in August of 1978 had been $31,000 a year—nothing, really—but in December, when they made me partner, they raised me to $65,000. They doubled my income and gave me the largest bonus ever given to any associate partner lawyer with the firm to that point: $10,000. That was all the money in the world to me, and I couldn’t believe it.

In 1980 I left that firm, which I loved dearly, because I wanted to be an entrepreneur and start my own firm. Two of the lawyers and I left, and one of them—George Carlton—is still with me as a partner at our firm, which is now called Godwin, Bowman & Martinez. We wanted to start what was known as one of the early “litigation boutiques.” It also enabled us to avoid the conflicts [in representation] that often came about in the larger firms, and I wanted to be able to do some work on a contingent-fee, alternative-billing basis. In larger firms, they only wanted law by the hour.

Respect For The Process

I certainly don’t want to say that I have a “natural ability” in the courtroom, but—maybe because of my family background and the way I was raised—I do seem to have a knack for relating to people, and particularly the common people that you would find in a courtroom on a jury. I love trying cases to juries. I never really enjoyed arguing cases on appeal, scholarly cases, talking to a panel of judges. I’m a jury lawyer.

I love telling them a story, outlining it for them so they can really understand it and relate to it, and then see if they can’t come back in favor of my client based upon the facts that are presented within the law. You’ve got to boil it down and make it simple. If you do that and they like you and they respect you and they trust you, they’ll give you about anything you want. You want to make it look easy, but, frankly, it’s very tough. The really good lawyers that I learned from over the years could make the most complex set of facts seem simple, so that a housewife or a small businessperson would understand and relate to it.

The greatest lawyer that I ever saw try a case was John O’Quinn in Houston. He had as close to a photographic memory as anybody I ever saw. He could pick a jury without a note, and remember names and talk to people about what their kids did, and he could examine witnesses. When I first met him, John told me, “Don, I want you to remember one thing: If you learn to relate to the common man, you can walk among kings.” There was a lot of depth in what he was saying.

Most lawyers cannot really communicate effectively to a jury. They’re very good at what they do—writing, reading, briefing—but they don’t know how to talk to a jury like people out on the street. While some lawyers have others do it for them, I like picking my own juries, because I want to establish a rapport with them from the very beginning. I think you win your case in the selection of your jury. You pick the wrong jury, no matter how good you and your client are, or how egregious they’ve been harmed, and you’re going to lose. You pick the right jury, and they’re going to relate to you and your client and listen to you. And then they’re likely going to go with you, if you present the case in the right way. So, I do everything I can to convince that jury panel to like me. I personalize it. I try to talk to them, not lecture them.

Most lawyers cannot really communicate effectively to a jury. They’re very good at what they do—writing, reading, briefing—but they don’t know how to talk to a jury like people out on the street. While some lawyers have others do it for them, I like picking my own juries, because I want to establish a rapport with them from the very beginning. I think you win your case in the selection of your jury. You pick the wrong jury, no matter how good you and your client are, or how egregious they’ve been harmed, and you’re going to lose. You pick the right jury, and they’re going to relate to you and your client and listen to you. And then they’re likely going to go with you, if you present the case in the right way. So, I do everything I can to convince that jury panel to like me. I personalize it. I try to talk to them, not lecture them.

Also, I think it’s critical when you’re a trial lawyer in the courtroom that you and every member of your team always appear to be totally professional and respectful of the judge and the jury. When that judge walks into that courtroom, you stand up—even if he says keep your seat. You’re in a hall of justice, after all, and you don’t want to do anything to diminish the importance of that.

You’re impressing upon the jury and the judge that you understand the rules, you know what they are, and you’re going to follow them to the letter because you believe in it and you believe in our system of justice. Juries don’t get paid very much, and they’re sitting over there, providing a service, giving of their valuable time, and they want to be respected. They want to know that the lawyers there are going to talk to them with the utmost respect and courtesy. Also, juries don’t ever want to see any lawyer—no matter how bad a judge may be mistreating him or her—be disrespectful of a judge, in my opinion. And, they certainly don’t want to see you be disrespectful to a witness.

Juries do want to come see a play. My experience has been that in trying cases—from divorce cases to complex estate and business cases—juries come in with no preconceived idea of what they’re going to see. But they’re hoping to see some “Perry Mason” or “L.A. Law,” or something like that. They don’t want to see a boring lawsuit. They want to see theater. They want to be entertained. And you have to be able to do some of that to be effective with them. Again, it’s about relating to people.

Beating British Petroleum

I’d say that at least 95 percent of the time in my career, I’ve tried jury cases. Now, conversely, the most significant case of my career—and the largest environmental case that was ever filed and consolidated and tried—was the litigation over the 2010 explosion of the British Petroleum/Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. I tried that as a lead lawyer for Halliburton before a federal judge, Carl Barbier, in New Orleans.

I had represented Dresser Industries and Halliburton in asbestos cases in Texas and all over the United States for about 20 years before they hired me on the BP litigation. I’d handled all those cases to the bitter end, and did the settlement of 382,000 asbestos and 25,000 silicosis cases all in one year, in 2002. That saved Halliburton from potentially going into bankruptcy.

Representing Halliburton as a lead lawyer in the BP/Deepwater Horizon case, I was involved in all the civil investigations in Washington, D.C., where we were before Congress and various House subcommittees and arguing about safety and all the issues related to the blowout. The litigation itself involved hundreds of thousands of plaintiffs on the Gulf Coast that were all brought together in multi-district litigation court under Judge Barbier, a wonderful United States Federal District Judge in New Orleans.

The case, of course, involved countless billions of dollars, because more than 4 million barrels of oil had been released into the gulf when the well blew out—the largest oil spill anywhere, ever in the world. I was hired by Halliburton in May 2010 and we showed up in Metairie, La., for the first hearings. By the time they were finished in late fall, thousands of plaintiffs had been filing lawsuits because of the damage all over the Gulf Coast—Houston, New Orleans, Miami Beach, Fla. They were represented by some of the most prominent, well-financed plaintiff’s lawyers in the country. Once we started down there with Judge Barbier in the late fall, he brought in Judge Sally Shushan, his magistrate judge, and he set a discovery schedule that pushed everybody unbelievably hard.

The big picture was determining the fault. BP owned the well, along with a group out of China. Transocean was drilling the well on the Deepwater Horizon vessel. Halliburton put all of the cement into the well, which went 18,000 feet below the water line. The cement went down around the casing, and that kept the hydrocarbons—the oil and gas—from escaping when you go down with your drilling bit. But the hydrocarbons did in fact blow through the cement and escape to the floor of the rig, and an explosion killed 11 people and injured countless others.

BP was alleging that Halliburton’s cement failed and was the underlying cause of the explosion. I argued that the cause was BP’s design of the well, and the way they had carelessly and recklessly allowed the well to be drilled, so that no matter what we put down there, it was never going to hold. In fact, Halliburton’s cement did give way, which allowed the hydrocarbons to escape, but it was—according to our position—through no fault of our own. And the judge agreed. He found that BP was at fault because of an improper drilling design, and he assessed no gross negligence against Halliburton. He found us 3 percent negligent, and he enforced an indemnity that I’d argued we had with BP. So we walked away from it with no liability.

I went into that case thinking it was going to take about six months to convince everybody to let us out of it. But it actually took four a half years to resolve. We got down there and, the further we went into it, the more entrenched BP became. They dug their heels in with hundreds of very fine lawyers from white-shoe firms in Chicago, New York, Washington, D.C., New Orleans, and Houston. BP had probably 300 lawyers on it, and I had 62 lawyers from my firm on it full-time, plus probably another 60 staff people. It’s amazing the amount of money BP spent, and they ended up losing.

We celebrated a little when it was over, but so much work had gone into it that we were mainly exhausted. I literally had been gone out of the office and away from my family every week for the better part of four and a half years, living in a little bitty motel room with no kitchen in it. Also, I knew what was facing me when I got through: I was going to come back to find that all my clients had gone to other law firms in the meantime. So I was going to have to start over, trying to rebuild my practice. Beginning about mid-2014, I had to get real busy again to generate the business to go on and pay the bills for two floors of lawyers and all that. And that’s what I did.

Looking For The Next Fight

The law has changed a lot since I started out. And I’m not sure it’s all changed for the good. For example, we now have restrictions on the amount of punitive damages that one can seek and recover in the Texas courts. While I’m not going to suggest that punitive damages ought to be without limitations, there are certain types of conduct that, if they’re found actually liable for it, I’m not sure there ought to be the limitations that we have today.

Another thing that I see happening that I really don’t like is the trend toward arbitration—trying to do away with jury trials. When you have these contracts that often require employees to come to work for you and sign on to do away with their right to a jury trial—they agree instead to do an alternative dispute resolution—that inhibits the employee’s ability to seek compensation for wrongdoing by errant employers. I’m a big proponent of jury trials; I believe that’s what our constitution provided for. That’s not to say I’m an advocate for everybody fighting and always being at the courthouse. But as people are wronged—whether they’re major corporations or individuals—they should have access to the courthouse, and there should be laws that would allow them to seek compensation if someone has taken advantage of them.

I see a lot of really bright young lawyers around today, but most of them don’t seem to understand and appreciate the business side of law. Years ago, when I started, you weren’t paid very much. In a lot of ways, these six-figure starting salaries—$130,000 to $170,000—have spoiled these young lawyers into thinking, look how good I am, look how successful I am, simply because of what they’re being paid. And that’s a result of one firm having to meet the challenge of another firm to be able to get the better talent. We’re paying for young lawyers that are requiring us to increase our rates to our clients and, in my opinion, that’s unfair in a lot of ways.

When I started, we worked six days a week, and sometimes half a day on Sunday. You can go to most of these law firms today on a Saturday and, if you find lawyers, it will be the partners—not the associates. The associates don’t understand the need to put in the time to do what they need to do, to really sharpen their skills to where they can become a great lawyer. What I think that will do is prepare you for the day when you’re going to have to be independent, and real success in any law firm comes with the lawyer’s ability to be independent. If the boss man they’re working for dies or retires, many of these lawyers find themselves with nothing to do. Or, if they ever want to have influence over their futures or income or positions in the firm, they need to have a bunch of business. And you don’t find too many young lawyers today out there focusing on trying to generate business at a high level.

I’m still working hard every day. I’m very, very busy with a lot of stuff right now—big cases. I want to keep going, and I’m always looking for the next fight. People say to me, “Don, when are you going to quit?” Why would I quit? My hobby is my law practice and my family. I love doing what I do. I remember when my dad was 75, I asked him when he was going to slow down or retire. He said, “As long as my health holds out and I enjoy what I’m doing, I’m going to keep doing it.” He lived another six years, until he was 81, and when he died he was working six days a week. So, just like with my dad, as long as I enjoy it and as long as my health holds out and the good Lord allows me to go on, I’m going to keep trying to help people resolve their problems.